- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Vasco da Gama

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2023 | Original: December 18, 2009

The Portuguese nobleman Vasco da Gama (1460-1524) sailed from Lisbon in 1497 on a mission to reach India and open a sea route from Europe to the East. After sailing down the western coast of Africa and rounding the Cape of Good Hope, his expedition made numerous stops in Africa before reaching the trading post of Calicut, India, in May 1498. Da Gama received a hero’s welcome back in Portugal, and was sent on a second expedition to India in 1502, during which he brutally clashed with Muslim traders in the region. Two decades later, da Gama again returned to India, this time as Portuguese viceroy; he died there of an illness in late 1524.

Vasco da Gama’s Early Life and First Voyage to India

Born circa 1460, Vasco da Gama was the son of a minor nobleman who commanded the fortress at Sines, located on the coast of the Alentejo province in southwestern Portugal. Little else is known about his early life, but in 1492 King John II sent da Gama to the port city of Setubal (south of Lisbon) and to the Algarve region to seize French ships in retaliation for French attacks on Portuguese shipping interests.

Did you know? By the time Vasco da Gama returned from his first voyage to India in 1499, he had spent more than two years away from home, including 300 days at sea, and had traveled some 24,000 miles. Only 54 of his original crew of 170 men returned with him; the majority (including da Gama's brother Paolo) had died of illnesses such as scurvy.

In 1497, John’s successor, King Manuel I (crowned in 1495), chose da Gama to lead a Portuguese fleet to India in search of a maritime route from Western Europe to the East. At the time, the Muslims held a monopoly of trade with India and other Eastern nations, thanks to their geographical position. Da Gama sailed from Lisbon that July with four vessels, traveling south along the coast of Africa before veering far off into the southern Atlantic in order to avoid unfavorable currents. The fleet was finally able to round the Cape of Good Hope at Africa’s southern tip in late November, and headed north along Africa’s eastern coast, making stops at what is now Mozambique, Mombasa and Malindi (both now in Kenya). With the help of a local navigator, da Gama was able to cross the Indian Ocean and reach the coast of India at Calicut (now Kozhikode) in May 1498.

Relations with Local Population & Rival Traders

Though the local Hindu population of Calicut initially welcomed the arrival of the Portuguese sailors (who mistook them for Christians), tensions quickly flared after da Gama offered their ruler a collection of relatively cheap goods as an arrival gift. This conflict, along with hostility from Muslim traders, led Da Gama to leave without concluding a treaty and return to Portugal. A much larger fleet, commanded by Pedro Alvares Cabral, was dispatched to capitalize on da Gama’s discoveries and secure a trading post at Calicut.

After Muslim traders killed 50 of his men, Cabral retaliated by burning 10 Muslim cargo vessels and killing the nearly 600 sailors aboard. He then moved on to Cochin, where he established the first Portuguese trading post in India. In 1502, King Manuel put da Gama in charge of another Indian expedition, which sailed that February. On this voyage, da Gama attacked Arab shipping interests in the region and used force to reach an agreement with Calicut’s ruler. For these brutal demonstrations of power, da Gama was vilified throughout India and the region. Upon his return to Portugal, by contrast, he was richly rewarded for another successful voyage.

Da Gama’s Later Life and Last Voyage to India

Da Gama had married a well-born woman sometime after returning from his first voyage to India; the couple would have six sons. For the next 20 years, da Gama continued to advise the Portuguese ruler on Indian affairs, but he was not sent back to the region until 1524, when King John III appointed him as Portuguese viceroy in India.

Da Gama arrived in Goa with the task of combating the growing corruption that had tainted the Portuguese government in India. He soon fell ill, and in December 1524 he died in Cochin. His body was later taken back to Portugal for burial there.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Vasco da Gama

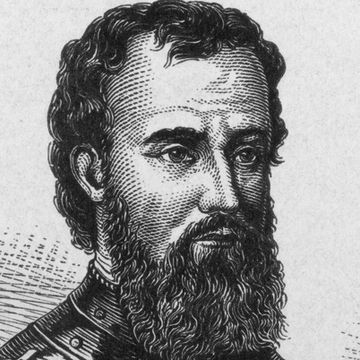

Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama was commissioned by the Portuguese king to find a maritime route to the East. He was the first person to sail directly from Europe to India.

(1460-1524)

Who Was Vasco Da Gama

In 1497, explorer Vasco da Gama was commissioned by the Portuguese king to find a maritime route to the East. His success in doing so proved to be one of the more instrumental moments in the history of navigation. He subsequently made two other voyages to India and was appointed as Portuguese viceroy in India in 1524.

Early Years

Da Gama was born into a noble family around 1460 in Sines, Portugal. Little is known about his upbringing except that he was the third son of Estêvão da Gama, who was commander of the fortress in Sines in the southwestern pocket of Portugal. When he was old enough, young da Gama joined the navy, where was taught how to navigate.

Known as a tough and fearless navigator, da Gama solidified his reputation as a reputable sailor when, in 1492, King John II of Portugal dispatched him to the south of Lisbon and then to the Algarve region of the country, to seize French ships as an act of vengeance against the French government for disrupting Portuguese shipping.

Following da Gama's completion of King John II's orders, in 1495, King Manuel took the throne, and the country revived its earlier mission to find a direct trade route to India. By this time, Portugal had established itself as one of the most powerful maritime countries in Europe.

Much of that was due to Henry the Navigator, who, at his base in the southern region of the country, had brought together a team of knowledgeable mapmakers, geographers and navigators. He dispatched ships to explore the western coast of Africa to expand Portugal's trade influence. He also believed that he could find and form an alliance with Prester John, who ruled over a Christian empire somewhere in Africa. Henry the Navigator never did locate Prester John, but his impact on Portuguese trade along Africa's east coast during his 40 years of explorative work was undeniable. Still, for all his work, the southern portion of Africa — what lay east — remained shrouded in mystery.

In 1487, an important breakthrough was made when Bartolomeu Dias discovered the southern tip of Africa and rounded the Cape of Good Hope. This journey was significant; it proved, for the first time, that the Atlantic and Indian oceans were connected. The trip, in turn, sparked a renewed interest in seeking out a trade route to India.

By the late 1490s, however, King Manuel wasn't just thinking about commercial opportunities as he set his sights on the East. In fact, his impetus for finding a route was driven less by a desire to secure for more lucrative trading grounds for his country, and more by a quest to conquer Islam and establish himself as the king of Jerusalem.

First Voyage

Historians know little about why exactly da Gama, still an inexperienced explorer, was chosen to lead the expedition to India in 1497. On July 8 of that year, he captained a team of four vessels, including his flagship, the 200-ton St. Gabriel , to find a sailing route to India and the East.

To embark on the journey, da Gama pointed his ships south, taking advantage of the prevailing winds along the coast of Africa. His choice of direction was also a bit of a rebuke to Christopher Columbus, who had believed he'd found a route to India by sailing east.

Following s months of sailing, he rounded the Cape of Good Hope and began making his way up the eastern coast of Africa, toward the uncharted waters of the Indian Ocean. By January, as the fleet neared what is now Mozambique, many of da Gama's crewmembers were sick with scurvy, forcing the expedition to anchor for rest and repairs for nearly one month.

In early March of 1498, da Gama and his crew dropped their anchors in the port of Mozambique, a Muslim city-state that sat on the outskirts of the east coast of Africa and was dominated by Muslim traders. Here, da Gama was turned back by the ruling sultan, who felt offended by the explorer's modest gifts.

By early April, the fleet reached what is now Kenya, before setting sail on a 23-day run that would take them across the Indian Ocean. They reached Calicut, India, on May 20. But da Gama's own ignorance of the region, as well as his presumption that the residents were Christians, led to some confusion. The residents of Calicut were actually Hindu, a fact that was lost on da Gama and his crew, as they had not heard of the religion.

Still, the local Hindu ruler welcomed da Gama and his men, at first, and the crew ended up staying in Calicut for three months. Not everyone embraced their presence, especially Muslim traders who clearly had no intention of giving up their trading grounds to Christian visitors. Eventually, da Gama and his crew were forced to barter on the waterfront in order to secure enough goods for the passage home. In August 1498, da Gama and his men took to the seas again, beginning their journey back to Portugal.

Da Gama's timing could not have been worse; his departure coincided with the start of a monsoon. By early 1499, several crew members had died of scurvy and in an effort to economize his fleet, da Gama ordered one of his ships to be burned. The first ship in the fleet didn't reach Portugal until July 10, nearly a full year after they'd left India.

In all, da Gama's first journey covered nearly 24,000 miles in close to two years, and only 54 of the crew's original 170 members survived.

Second Voyage

When da Gama returned to Lisbon, he was greeted as a hero. In an effort to secure the trade route with India and usurp Muslim traders, Portugal dispatched another team of vessels, headed by Pedro Álvares Cabral. The crew reached India in just six months, and the voyage included a firefight with Muslim merchants, where Cabral's crew killed 600 men on Muslim cargo vessels. More important for his home country, Cabral established the first Portuguese trading post in India.

In 1502, da Gama helmed another journey to India that included 20 ships. Ten of the ships were directly under his command, with his uncle and nephew helming the others. In the wake of Cabral's success and battles, the king charged da Gama to further secure Portugal's dominance in the region.

To do so, da Gama embarked on one of the most gruesome massacres of the exploration age. He and his crew terrorized Muslim ports up and down the African east coast, and at one point, set ablaze a Muslim ship returning from Mecca, killing the several hundreds of people (including women and children) who were on board. Next, the crew moved to Calicut, where they wrecked the city's trade port and killed 38 hostages. From there, they moved to the city of Cochin, a city south of Calicut, where da Gama formed an alliance with the local ruler.

Finally, on February 20, 1503, da Gama and his crew began to make their way home. They reached Portugal on October 11 of that year.

Later Years and Death

Little was recorded about da Gama's return home and the reception that followed, though it has been speculated that the explorer felt miffed at the recognition and compensation for his exploits.

Married at this time, and the father of six sons, da Gama settled into retirement and family life. He maintained contact with King Manuel, advising him on Indian matters, and was named count of Vidigueira in 1519. Late in life, after the death of King Manuel, da Gama was asked to return to India, in an effort to contend with the growing corruption from Portuguese officials in the country. In 1524, King John III named da Gama Portuguese viceroy in India.

That same year, da Gama died in Cochin — the result, it has been speculated, from possibly overworking himself. His body was sailed back to Portugal, and buried there, in 1538.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Vasco da Gama

- Birth Year: 1460

- Birth City: Sines

- Birth Country: Portugal

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama was commissioned by the Portuguese king to find a maritime route to the East. He was the first person to sail directly from Europe to India.

- World Politics

- Nationalities

- Death Year: 1524

- Death date: December 24, 1524

- Death City: Cochin

- Death Country: India

- I am not the man I once was. I do not want to go back in time, to be the second son, the second man.

- I am not afraid of the darkness. Real death is preferable to a life without living.

- We left from Restelo one Saturday, the 8th day of July of the said year, 1479, on out journey. May God our Lord allow us to complete it in His service.

- There was great rejoicing, thanks being rendered to God for having extricated us from the hands of people who had no more sense than beasts.

European Explorers

Christopher Columbus

10 Famous Explorers Who Connected the World

Sir Walter Raleigh

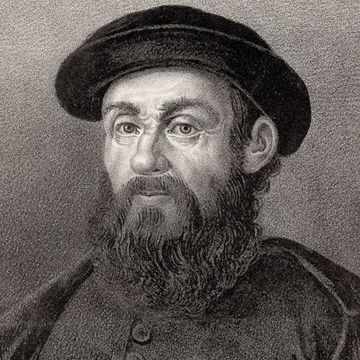

Ferdinand Magellan

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Bartolomeu Dias

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

- Inventors and Inventions

- Philosophers

- Film, TV, Theatre - Actors and Originators

- Playwrights

- Advertising

- Military History

- Politicians

- Publications

- Visual Arts

John Cabot - North American Trail-blazer

Contribution to British Heritage.

Legacy and Success

General information.

- John Cabot en.wikipedia.org

You might also like

The Ages of Exploration

Vasco da gama, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

Portuguese explorer and navigator who found a direct sea route from Europe to Asia, and was the first European to sail to India by going around Africa.

Name : Vasco da Gama [vas-koh]; [(Portuguese) vahsh-koo] [duh gah-muh]

Birth/Death : ca. 1460 CE - 1524 CE

Nationality : Portuguese

Birthplace : Portugal

Portrait of Vasco da Gama by artist Antonio Manuel da Fonseca in 1838. Vasco da Gama, (c.1469 – 1524) was a Portuguese explorer, one of the most successful in the European Age of Discovery and the commander of the first ships to sail directly from Europe to India. (Credit: National Maritime Museum)

Introduction Vasco da Gama was a Portuguese explorer who sailed to India from Europe. Gold, spices, and other riches were valuable in Europe. But they had to navigate long ways over sea and land to reach them in Asia. Europeans during this time were looking to find a faster way to reach India by sailing around Africa. Da Gama accomplished the task. By doing so, he helped open a major trade route to Asia. Portugal celebrated his success, and his voyage launched a new era of discovery and world trade.

Biography Early Life Vasco da Gama’s exact birthdate and place is unknown. It is believed he was born between 1460 and 1469 in Sines, Portugal. 1 He was the third son to his parents. His father, Estêvão da Gama, was a knight in the Duke of Viseu’s court; and his mother was a noblewoman named Isabel Sodré. 2 His father’s role in the court would have allowed young Vasco to have a good education. But because he lived close to a seaport town, he probably also learned about ships and navigation. Vasco attended school in a larger village about 70 miles from Sines called Évora. Here, he learned advanced mathematics, and studied principles of navigation. By fifteen he became familiar with trading ships that were docked in port. By the age of twenty, he was the captain of a ship. 3 These skills would all make him an acceptable choice to lead an expedition to India.

Vasco da Gama’s maritime career was during the period when Portugal was searching for a trade route around Africa to India. The Ottoman Empire controlled almost all European trade routes to Asia. This meant they could, and did, charge high prices for ships passing through ports. Prince Henry of Portugal – also called Prince Henry the Navigator – began Portugal’s great age of exploration. From about 1419 until his death in 1460, he sent several sailing expeditions down the coast of Africa. 4 In 1481, King John II of Portugal began sending expeditions to find a sea route around the southern shores of Africa. Many explorers made several attempts. It was Bartolomeu Dias who was the first to round Africa and make it to the Indian Ocean in 1488. But he was forced to head back to Portugal before he could make it to India. When Manuel I became king of Portugal in 1495, he continued efforts to open a trade route to India by going around Africa. Although other people were considered for the job, Manuel I finally chose thirty-seven year old Vasco da Gama for this task.

Voyages Principal Voyage On 8 July 1497 Vasco da Gama sailed from Lisbon with a fleet of four ships with a crew of 170 men from Lisbon. Da Gama commanded the Sao Gabriel . Paulo da Gama – brother to Vasco – commanded the São Rafael , a three masted ship. There was also the caravel Berrio , and a storeship São Maria . Bartolomeu Dias also sailed with da Gama, and gave helpful advice for navigating down the African coast. They sailed past the Canary Islands, and reached the Cape Verde islands by July 26. They stayed about a week, then continued sailing on August 3. To help avoid the storms and strong currents near the Gulf of Guinea, da Gama and his fleet sailed out into the South Atlantic and swung down to the Cape of Good Hope. Storms still delayed them for a while. They rounded the cape on November 22 and three days later anchored at Mossel Bay, South Africa. 5 They began sailing again on December 8. They anchored for a bit in January near Mozambique at the Rio do Cobre (Copper River) and continued on until they reached the Rio dos Bons Sinais (River of Good Omens). Here they erected a statue in the name of Portugal.

They stayed here for a month because much of the crew were sick from scurvy – a disease caused by lack of Vitamin C. 6 Da Gama’s fleet eventually began sailing again. On March 2 they reached the Island of Mozambique. After trading with the local Muslim merchants, da Gama sailed on once more stopping briefly in Malindi (in present day Kenya). He hired a pilot to help him navigate through the Indian Ocean. They sailed for 23 days, and on May 20, 1498 they reached India. 7 They headed for Kappad, India near the large city of Calicut. In Calicut, da Gama met with the king. But the king of Calicut was not impressed with da Gama, and the gifts he brought as offering. They spent several months trading in India, and studying their customs. They left India at the end of August. He visited the Anjidiv Island near Goa, and then once more stopped in Malindi in January 1499. Many of his crew were dying of scurvy. He had the São Rafael burned to help contain the illness. Da Gama finally returned to Portugal in September 1499. Manuel I praised da Gama’s success, and gave him money and a new title of admiral.

Subsequent Voyages Vasco da Gama’s later voyages were less friendly with the people he met. He sailed once again beginning in February 1502 with a fleet of 10 ships. They stopped at the Cape Verdes Islands, Mozambique, and then sailed to Kilwa (in modern day Tanzania). Da Gama threatened their leader, and forced him and his people to swear loyalty to the king of Portugal. At Calicut, he bombarded the port, and caused the death of several Muslim traders. Again, later at Cochin, they fought with Arab ships, and sent them into flight. 8 Da Gama was paving the way for an expanded Portuguese empire. This came at the cruel treatment of East African and South Asian people. Finally, on February 20, 1503 da Gama began the return journey home arriving on October 11 1503. King Manuel I died in 1521, and King John III became ruler. He made da Gama a Portuguese viceroy in India. 9 King John III sent da Gama to India to stop the corruption and settle administrative problems of the Portuguese officials. Da Gama’s third journey would be his last.

Later Years and Death After he had returned from his first trip, in 1500 Vasco da Gama had married Caterina de Ataíde. They had six sons, and lived in the town Évora. Da Gama continued advising on Indian affairs until he was sent overseas again in 1524. Vasco da Gama left Portugal for India, and arrived at Goa in September 1524. Da Gama quickly re-established order among the Portuguese leaders. By the end of the year he fell ill. Vasco da Gama died on December 24, 1524 in Cochin, India. He was buried in the local church. In 1539, his remains were brought back to Portugal.

Legacy Vasco De Gama was the first European to find an ocean trading route to India. He accomplished what many explorers before him could not do. His discovery of this sea route helped the Portuguese establish a long-lasting colonial empire in Asia and Africa. The new ocean route around Africa allowed Portuguese sailors to avoid the Arab trading hold in the Mediterranean and Middle East. Better access to the Indian spice routes boosted Portugal’s economy. Vasco da Gama opened a new world of riches by opening up an Indian Ocean route. His voyage and explorations helped change the world for Europeans.

- Emmanuel Akyeampong and Henry Louis Gates, Dictionary of African Biography (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2012), 415.

- Akyeampong and Gates, Dictionary of African Biography , 415.

- Patricia Calvert, Vasco Da Gama: So Strong a Spirit (Tarrytown: Benchmark Books, 2005), 11-12.

- Aileen Gallagher, Prince Henry, the Navigator: Pioneer of Modern Exploration (New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2003), 5.

- Kenneth Pletcher, ed., The Britannica Guide to Explorers and Explorations That Changed the Modern World (New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2009), 54.

- Pletcher, The Britannica Guide, 55.

- Pletcher, The Britannica Guide , 55.

- Pletcher, The Britannica Guide , 57.

- Pletcher, The Britannica Guide , 58.

Bibliography

Akyeampong, Emmanuel, and Henry Louis Gates. Dictionary of African Biography . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Calvert, Patricia. Vasco Da Gama: So Strong a Spirit . Tarrytown: Benchmark Books, 2005.

Gallagher, Aileen. Prince Henry, the Navigator: Pioneer of Modern Exploration . New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2003.

Pletcher, Kenneth ed. The Britannica Guide to Explorers and Explorations That Changed the Modern World. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2009.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Hunter, Douglas . "John Cabot". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 19 May 2017, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot. Accessed 27 April 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 19 May 2017, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot. Accessed 27 April 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Hunter, D. (2017). John Cabot. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Hunter, Douglas . "John Cabot." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 07, 2008; Last Edited May 19, 2017.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 07, 2008; Last Edited May 19, 2017." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "John Cabot," by Douglas Hunter, Accessed April 27, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "John Cabot," by Douglas Hunter, Accessed April 27, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Article by Douglas Hunter

Published Online January 7, 2008

Last Edited May 19, 2017

Early Years in Venice

John Cabot had a complex and shadowy early life. He was probably born before 1450 in Italy and was awarded Venetian citizenship in 1476, which meant he had been living there for at least fifteen years. People often signed their names in different ways at this time, and Cabot was no exception. In one 1476 document he identified himself as Zuan Chabotto, which gives a clue to his origins. It combined Zuan, the Venetian form for Giovanni, with a family name that suggested an origin somewhere on the Italian peninsula, since a Venetian would have spelled it Caboto. He had a Venetian wife, Mattea, and three sons, one of whom, Sebastian, rose to the rank of pilot-major of Spain for the Indies trade. Cabot was a merchant; Venetian records identify him as a hide trader, and in 1483 he sold a female slave in Crete. He was also a property developer in Venice and nearby Chioggia.

Cabot in Spain

In 1488, Cabot fled Venice with his family because he owed prominent people money. Where the Cabot family initially went is unknown, but by 1490 John Cabot was in Valencia, Spain, which like Venice was a city of canals. In 1492, he partnered with a Basque merchant named Gaspar Rull in a proposal to build an artificial harbour for Valencia on its Mediterranean coast. In April 1492, the project captured the enthusiasm of Fernando (Ferdinand), king of Aragon and husband of Isabel, queen of Castille, who together ruled what is now a unified Spain. The royal couple had just agreed to send Christopher Columbus on his now-famous voyage to the Americas. In the autumn of 1492, Fernando encouraged the governor-general of Valencia to find a way to finance Cabot’s harbour scheme. However, in March 1493, the council of Valencia decided it could not fund Cabot’s plan. Despite Fernando’s attempt to move the project forward that April, the scheme collapsed.

Cabot disappeared from the historical record until June 1494, when he resurfaced in another marine engineering plan dear to the Spanish monarchs. He was hired to build a fixed bridge link in Seville to its maritime centre, the island of Triana in the Guadalquivir River, which otherwise was serviced by a troublesome floating one. Though Columbus had reached the Americas, he believed he had found land on the eastern edge of Asia, and Seville had been chosen as the headquarters of what Spain imagined was a lucrative transatlantic trade route. Cabot’s assignment thus was an important one, but something went wrong. In December 1494, a group of leading citizens of Seville gathered, unhappy with Cabot’s lack of progress, given the funds he had been provided. At least one of them thought he should be banished from the city. By then, Cabot probably had left town.

Cabot in England

Following the demise of Cabot’s Seville bridge project, the marine engineer again disappeared from the historical record. In March 1496 he resurfaced, this time as the commander of a proposed westward voyage under the flag of the King of England, Henry VII. Although there is no documentary proof, during Cabot’s absence from the historical record, between April 1493 and June 1494, he could have sailed with Columbus’s second voyage to the Caribbean. Most of the names of the over 1,000 people who accompanied Columbus weren’t recorded; however, Cabot could have been among the marine engineers on the voyage’s 17 ships who were expected to construct a harbour facility in what is now Haiti. Had Cabot been present on this journey, Henry VII would have had some basis to believe the would-be Venetian explorer could make a similar voyage to the far side of the Atlantic. It would help explain why Henry VII hired Cabot, a foreigner with a problematic résumé and no known nautical expertise, to make such a journey.

On 5 March 1496, Henry awarded Cabot and his three sons a generous letters patent, a document granting them the right to explore and exploit areas unknown to Christian monarchs. The Cabots were authorized to sail to “all parts of the eastern, western and northern sea, under our banners, flags and ensigns,” with as many as five ships, manned and equipped at their own expense. The Cabots were to “find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.” The Cabots would serve as Henry’s “vassals, and governors lieutenants and deputies” in whatever lands met the criteria of the patent, and they were given the right to “conquer, occupy and possess whatsoever towns, castles, cities and islands by them discovered.” With the letters patent, the Cabots could secure financial backing. Two payments were made in April and May 1496 to John Cabot by the House of Bardi (a family of Florentine merchants) to fund his search for “the new land,” suggesting his investors thought he was looking for more than a northern trade route to Asia.

First Voyage (1496)

Cabot’s first voyage departed Bristol, England, in 1496. Sailing westward in the north Atlantic was no easy task. The prevailing weather patterns track from west to east, and ships of Cabot’s time could scarcely sail toward the wind. No first-hand accounts of Cabot’s first attempt to sail west survive. Historians only know that it was a failure, with Cabot apparently rebuffed by stormy weather.

Second Voyage (1497)

Cabot mounted a second attempt from Bristol in May 1497, using a ship called the Matthew . It may have been a happy coincidence that its name was the English version of Cabot’s wife’s name, Mattea. There are no records of the ship’s individual crewmembers, and all the accounts of the voyage are second-hand — a remarkable lack of documentation for a voyage that would be the foundation of England’s claim to North America.

Historians have long debated exactly where Cabot explored. The most authoritative report of his journey was a letter by a London merchant named Hugh Say. Written in the winter of 1497-98, but only discovered in Spanish archives in the mid-1950s, Say’s letter (written in Spanish) was addressed to a “great admiral” in Spain who may have been Columbus.

The rough latitudes Say provided suggest Cabot made landfall around southern Labrador and northernmost Newfoundland , then worked his way southeast along the coast until he reached the Avalon Peninsula , at which point he began the journey home. Cabot led a fearful crew, with reports suggesting they never ventured more than a crossbow’s shot into the land. They saw two running figures in the woods that might have been human or animal and brought back an unstrung bow “painted with brazil,” suggesting it was decorated with red ochre by the Beothuk of Newfoundland or the Innu of Labrador. He also brought back a snare for capturing game and a needle for making nets. Cabot thought (wrongly) there might be tilled lands, written in Say’s letter as tierras labradas , which may have been the source of the name for Labrador. Say also said it was certain the land Cabot coasted was Brasil, a fabled island thought to exist somewhere west of Ireland.

Others who heard about Cabot’s voyage suggested he saw two islands, a misconception possibly resulting from the deep indentations of Newfoundland’s Conception and Trinity Bays, and arrived at the coast of East Asia. Some believed he had reached another fabled island, the Isle of Seven Cities, thought to exist in the Atlantic.

There were also reports Cabot had found an enormous new fishery. In December 1497, the Milanese ambassador to England reported hearing Cabot assert the sea was “swarming with fish, which can be taken not only with the net, but in baskets let down with a stone.” The fish of course were cod , and their abundance on the Grand Banks later laid the foundation for Newfoundland’s fishing industry.

Third Voyage (1498)

Henry VII rewarded Cabot with a royal pension on December 1497 and a renewed letters patent in February 1498 that gave him additional rights to help mount the next voyage. The additional rights included the ability to charter up to six ships as large as 200 tons. The voyage was again supposed to be mounted at Cabot’s expense, although the king personally invested in one participating ship. Despite reports from the 1497 voyage of masses of fish, no preparations were made to harvest them.

A flotilla of probably five ships sailed in early May. What became of it remains a mystery. Historians long presumed, based on a flawed account by the chronicler Polydore Vergil, that all the ships were lost, but at least one must have returned. A map made by Spanish cartographer Juan de la Cosa in 1500 — one of the earliest European maps to incorporate the Americas — included details of the coastline with English place names, flags and the notation “the sea discovered by the English.” The map suggests Cabot’s voyage ventured perhaps as far south as modern New England and Long Island.

Cabot’s royal pension did continue to be paid until 1499, but if he was lost on the 1498 voyage, it may only have been collected in his absence by one of his sons, or his widow, Mattea.

Despite being so poorly documented, Cabot’s 1497 voyage became the basis of English claims to North America. At the time, the westward voyages of exploration out of Bristol between 1496 and about 1506, as well as one by Sebastian Cabot around 1508, were probably considered failures. Their purpose was to secure trade opportunities with Asia, not new fishing grounds, which not even Cabot was interested in, despite praising the teeming schools. Instead of trade with Asia, Cabot and his Bristol successors found an enormous land mass blocking the way and no obvious source of wealth.

- Newfoundland and Labrador

Further Reading

Douglas Hunter, The Race to the New World: Christopher Columbus, John Cabot and a Lost History of Discovery (2012).

External Links

Heritage Newfoundland and Labrador A biography of John Cabot from this site sponsored by Memorial University.

Dictionary of Canadian Biography An account of John Cabot’s life from the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Recommended

Giovanni da verrazzano, jacques cartier.

Sir Humphrey Gilbert: Elizabethan Explorer

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot)

Introduction, general overviews.

- Encyclopedia Entries

- Birth and Early Life

- The 1496 Voyage

- The 1497 Voyage

- The 1498 Voyage

- Funding of Voyages

- Sebastiano Caboto, Son (d. 1557)

- Maps and Cartography

- Early English Voyages (pre-Caboto)

- Later English Voyages (post-Caboto)

- Internet Resources

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Maps in the Atlantic World

- Pre-Columbian Transatlantic Voyages

- Tudor and Stuart Britain in the Wider World, 1485–1685

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Ecology and Nineteenth-Century Anglophone Atlantic Literature

- Science and Technology (in Literature of the Atlantic World)

- The Danish Atlantic World

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot) by Francesco Guidi Bruscoli LAST REVIEWED: 29 November 2022 LAST MODIFIED: 29 November 2022 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199730414-0374

Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot, b. c. 1450–d. c . 1500) was an Italian navigator credited to be the first European to set foot in North America after the Norse, during an expedition of 1497 carried out under the English flag. Little is known about his origins, although he certainly took up Venetian citizenship, implying origin elsewhere. He was known as Zuan Chabotto in Venice, and he presented himself as a Venetian when he moved to England. As early as the late sixteenth/early seventeenth century, Richard Hakluyt and Samuel Purchas praised Caboto’s pioneering “discoveries” (despite some confusion between the role of Giovanni and that of his son). But it was especially from 1897 (the 400th anniversary of his landing) that—following new archival discoveries—his achievement as an explorer was celebrated. Until then his role had been overshadowed by that of his son Sebastian, who in part because of the influence of Sebastian’s own accounts, had been credited with being in charge of the voyages. It was in particular Henry Harrisse, in John Cabot, the Discoverer of North America, and Sebastian his Son: A Chapter of the Maritime History of England under the Tudors, 1496–1557 (London: Stevens, 1896), who revived the figure of Giovanni, while at the same time lambasting Sebastiano as an impostor. In the same period, more or less co-incident with the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s 1492 voyage, general interest in voyages of exploration revived also in Italy, although studies on Caboto mainly focused on his origin. In the 1940s new documentary discoveries threw some light on Caboto’s years both in Spain and in Venice. In the 1950s the discovery of John Day’s letter in the Simancas archive stimulated a new wave of studies, for the letter hints at a previously unknown voyage of 1496, provides many technical details concerning the 1497 voyage (thus opening debate on the latitude of the landing), and alludes to earlier discoveries. The most important study, still a crucial reference for studies on Caboto, is James A. Williamson’s The Cabot Voyages and Bristol Discovery under Henry VII (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press/Hakluyt Society, 2nd Series, vol. 120, 1962). For the 500th anniversary of the landing, in 1997, several conferences were organized, in many cases leading to the publication of proceedings. The most relevant recent advances, however, have been made within the framework of the Cabot Project, based at the University of Bristol. Following unpublished leads left behind by deceased scholar Alwyn Ruddock, Evan Jones and others have proposed new hypotheses, and uncovered the first known financiers of the 1497 voyage.

The volume of literature on Giovanni Caboto is overwhelming. New waves of publications coincided either with the celebration of anniversaries (especially in 1897 and 1997) or with the discovery of new documents, as summarized by Luzzana Caraci 1999 . In Italian the first analytical study of Caboto’s achievements was Almagià 1937 . In English the classic work (still seminal) is Williamson 1962 . Countless scholars and writers have published on Caboto’s voyages before and since. Among the most recent academic publications, Pope 1997 discusses at length the possible landfall of the 1497 voyage, still claimed by various Canadian regions, including Cape Bonavista (Newfoundland) and Cape Breton (Nova Scotia), whereas Jones 2008 sets the agenda for new streams of research to be undertaken in order to substantiate or rebut novel claims made by deceased historian Alwyn Ruddock (d. 2005). Recent popular literature includes Hunter 2011 , which takes a broader approach including Columbus’s voyages, and Jones and Condon 2016 , which summarizes current knowledge and is the prelude to a forthcoming academic publication.

Almagià, Roberto. Gli italiani primi scopritori dell’America . Rome: La Libreria dello Stato, 1937.

Voluminous (and rare) publication in Italian on Italian “first discoverers” of America. Starts from Columbus, and devotes several pages to Caboto. It also includes tables and maps. Critically discusses documents relating to the life and voyages of Caboto (and his son).

Hunter, Douglas. The Race to the New World: Christopher Columbus, John Cabot, and a Lost History of Discovery . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

A popular history book, aimed at comparing the figures, the careers, and the achievements of Christopher Columbus and Giovanni Caboto. Includes the hypothesis (not backed by any documentary evidence) that Caboto might have accompanied Columbus on his second voyage of 1493.

Jones, Evan T. “Alwyn Ruddock: ‘John Cabot and the Discovery of America.’” Historical Research 81 (2008): 224–254.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2281.2007.00422.x

Discusses claims made by late historian Alwyn Ruddock concerning new discoveries relating to Caboto’s voyages. This article originated new archival research aimed at substantiating or clarifying Ruddock’s claims. See also The Cabot Project , cited under Internet Resources .

Jones, Evan T., and M. Condon. Cabot and Bristol’s Age of Discovery: The Bristol Discovery Voyages 1480–1508 . Bristol, UK: University of Bristol, 2016.

Aimed at a general audience, this book presents an updated summary of what we currently know about Caboto and his voyages. It also discusses claims made by the late historian Alwyn Ruddock concerning the discovery of new documents. Also available online .

Luzzana Caraci, Ilaria. “Giovanni Caboto cinquecento anni dopo.” In Giovanni Caboto e le vie dell’Atlantico settentrionale . Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Roma, 29 settembre–1 ottobre 1997). Edited by Marcella Arca Petrucci and Simonetta Conti, 51–68. Rome: CISGE, 1999.

Useful and articulated—albeit brief—summary of the main advancement in the knowledge of Caboto’s life and voyages from the sixteenth century (until 1997).

Pope, Peter. The Many Landfalls of John Cabot . Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

DOI: 10.3138/9781442681699

Discusses the current knowledge about Caboto, but also the claims of his son Sebastiano (denying his participation in his father’s voyage). Much space is devoted to the possible landfalls of the 1497 voyage and to the celebrations of 1897 (400th anniversary of the landing), when “anglophone/francophone cultural tensions [and] competition between Canada and Newfoundland” (p. 8) sparked debate on the landfall itself.

Williamson, James A. The Cabot Voyages and Bristol Discovery under Henry VII . Hakluyt Society Works, 2nd Series, Vol. 120. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1962.

Albeit dated, it is still the fundamental reference for sources concerning the voyages of John Cabot, as well as his son Sebastian’s and other Bristol voyages. A long introduction summarizes and compares all the sources and offers a considered narrative. It also includes an Appendix by R.A. Skelton, “The Cartography of the Voyages.” The volume reworks, with new documents added, an earlier study of 1929.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Atlantic History »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abolition of Slavery

- Abolitionism and Africa

- Africa and the Atlantic World

- African American Religions

- African Religion and Culture

- African Retailers and Small Artisans in the Atlantic World

- Age of Atlantic Revolutions, The

- Alexander von Humboldt and Transatlantic Studies

- America, Pre-Contact

- American Revolution, The

- Anti-Catholicism and Anti-Popery

- Army, British

- Art and Artists

- Asia and the Americas and the Iberian Empires

- Atlantic Biographies

- Atlantic Creoles

- Atlantic History and Hemispheric History

- Atlantic Migration

- Atlantic New Orleans: 18th and 19th Centuries

- Atlantic Trade and the British Economy

- Atlantic Trade and the European Economy

- Bacon's Rebellion

- Barbados in the Atlantic World

- Barbary States

- Berbice in the Atlantic World

- Black Atlantic in the Age of Revolutions, The

- Bolívar, Simón

- Borderlands

- Bourbon Reforms in the Spanish Atlantic, The

- Brazil and Africa

- Brazilian Independence

- Britain and Empire, 1685-1730

- British Atlantic Architectures

- British Atlantic World

- Buenos Aires in the Atlantic World

- Cabato, Giovanni (John Cabot)

- Cannibalism

- Captain John Smith

- Captivity in Africa

- Captivity in North America

- Caribbean, The

- Cartier, Jacques

- Catholicism

- Cattle in the Atlantic World

- Central American Independence

- Central Europe and the Atlantic World

- Chartered Companies, British and Dutch

- Chinese Indentured Servitude in the Atlantic World

- Church and Slavery

- Cities and Urbanization in Portuguese America

- Citizenship in the Atlantic World

- Class and Social Structure

- Coastal/Coastwide Trade

- Cod in the Atlantic World

- Colonial Governance in Spanish America

- Colonial Governance in the Atlantic World

- Colonialism and Postcolonialism

- Colonization, Ideologies of

- Colonization of English America

- Communications in the Atlantic World

- Comparative Indigenous History of the Americas

- Confraternities

- Constitutions

- Continental America

- Cook, Captain James

- Cortes of Cádiz

- Cosmopolitanism

- Credit and Debt

- Creek Indians in the Atlantic World, The

- Creolization

- Criminal Transportation in the Atlantic World

- Crowds in the Atlantic World

- Death in the Atlantic World

- Demography of the Atlantic World

- Diaspora, Jewish

- Diaspora, The Acadian

- Disease in the Atlantic World

- Domestic Production and Consumption in the Atlantic World

- Domestic Slave Trades in the Americas

- Dreams and Dreaming

- Dutch Atlantic World

- Dutch Brazil

- Dutch Caribbean and Guianas, The

- Early Modern Amazonia

- Early Modern France

- Economy and Consumption in the Atlantic World

- Economy of British America, The

- Edwards, Jonathan

- Emancipation

- Empire and State Formation

- Enlightenment, The

- Environment and the Natural World

- Europe and Africa

- Europe and the Atlantic World, Northern

- Europe and the Atlantic World, Western

- European Enslavement of Indigenous People in the Americas

- European, Javanese and African and Indentured Servitude in...

- Evangelicalism and Conversion

- Female Slave Owners

- First Contact and Early Colonization of Brazil

- Fiscal-Military State

- Forts, Fortresses, and Fortifications

- Founding Myths of the Americas

- France and Empire

- France and its Empire in the Indian Ocean

- France and the British Isles from 1640 to 1789

- Free People of Color

- Free Ports in the Atlantic World

- French Army and the Atlantic World, The

- French Atlantic World

- French Emancipation

- French Revolution, The

- Gender in Iberian America

- Gender in North America

- Gender in the Atlantic World

- Gender in the Caribbean

- George Montagu Dunk, Second Earl of Halifax

- Georgia in the Atlantic World

- German Influences in America

- Germans in the Atlantic World

- Giovanni da Verrazzano, Explorer

- Glorious Revolution

- Godparents and Godparenting

- Great Awakening

- Green Atlantic: the Irish in the Atlantic World

- Guianas, The

- Haitian Revolution, The

- Hanoverian Britain

- Havana in the Atlantic World

- Hinterlands of the Atlantic World

- Histories and Historiographies of the Atlantic World

- Hunger and Food Shortages

- Iberian Atlantic World, 1600-1800

- Iberian Empires, 1600-1800

- Iberian Inquisitions

- Idea of Atlantic History, The

- Impact of the French Revolution on the Caribbean, The

- Indentured Servitude

- Indentured Servitude in the Atlantic World, Indian

- India, The Atlantic Ocean and

- Indigenous Knowledge

- Indigo in the Atlantic World

- Internal Slave Migrations in the Americas

- Interracial Marriage in the Atlantic World

- Ireland and the Atlantic World

- Iroquois (Haudenosaunee)

- Islam and the Atlantic World

- Itinerant Traders, Peddlers, and Hawkers

- Jamaica in the Atlantic World

- Jefferson, Thomas

- Jews and Blacks

- Labor Systems

- Land and Propert in the Atlantic World

- Language, State, and Empire

- Languages, Caribbean Creole

- Latin American Independence

- Law and Slavery

- Legal Culture

- Leisure in the British Atlantic World

- Letters and Letter Writing

- Literature and Culture

- Literature of the British Caribbean

- Literature, Slavery and Colonization

- Liverpool in The Atlantic World 1500-1833

- Louverture, Toussaint

- Manumission

- Maritime Atlantic in the Age of Revolutions, The

- Markets in the Atlantic World

- Maroons and Marronage

- Marriage and Family in the Atlantic World

- Material Culture in the Atlantic World

- Material Culture of Slavery in the British Atlantic

- Medicine in the Atlantic World

- Mental Disorder in the Atlantic World

- Mercantilism

- Merchants in the Atlantic World

- Merchants' Networks

- Migrations and Diasporas

- Minas Gerais

- Mining, Gold, and Silver

- Missionaries

- Missionaries, Native American

- Money and Banking in the Atlantic Economy

- Monroe, James

- Morris, Gouverneur

- Music and Music Making

- Napoléon Bonaparte and the Atlantic World

- Nation and Empire in Northern Atlantic History

- Nation, Nationhood, and Nationalism

- Native American Histories in North America

- Native American Networks

- Native American Religions

- Native Americans and Africans

- Native Americans and the American Revolution

- Native Americans and the Atlantic World

- Native Americans in Cities

- Native Americans in Europe

- Native North American Women

- Native Peoples of Brazil

- Natural History

- Networks for Migrations and Mobility

- Networks of Science and Scientists

- New England in the Atlantic World

- New France and Louisiana

- New York City

- Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World

- Nineteenth-Century France

- Nobility and Gentry in the Early Modern Atlantic World

- North Africa and the Atlantic World

- Northern New Spain

- Novel in the Age of Revolution, The

- Oceanic History

- Pacific, The

- Paine, Thomas

- Papacy and the Atlantic World

- People of African Descent in Early Modern Europe

- Pets and Domesticated Animals in the Atlantic World

- Philadelphia

- Philanthropy

- Phillis Wheatley

- Plantations in the Atlantic World

- Poetry in the British Atlantic

- Political Participation in the Nineteenth Century Atlantic...

- Polygamy and Bigamy

- Port Cities, British

- Port Cities, British American

- Port Cities, French

- Port Cities, French American

- Port Cities, Iberian

- Ports, African

- Portugal and Brazile in the Age of Revolutions

- Portugal, Early Modern

- Portuguese Atlantic World

- Poverty in the Early Modern English Atlantic

- Pregnancy and Reproduction

- Print Culture in the British Atlantic

- Proprietary Colonies

- Protestantism

- Quebec and the Atlantic World, 1760–1867

- Race and Racism

- Race, The Idea of

- Reconstruction, Democracy, and United States Imperialism

- Red Atlantic

- Refugees, Saint-Domingue

- Religion and Colonization

- Religion in the British Civil Wars

- Religious Border-Crossing

- Religious Networks

- Representations of Slavery

- Republicanism

- Rice in the Atlantic World

- Rio de Janeiro

- Russia and North America

- Saint Domingue

- Saint-Louis, Senegal

- Salvador da Bahia

- Scandinavian Chartered Companies

- Science, History of

- Scotland and the Atlantic World

- Sea Creatures in the Atlantic World

- Second-Hand Trade

- Settlement and Region in British America, 1607-1763

- Seven Years' War, The

- Sex and Sexuality in the Atlantic World

- Shakespeare and the Atlantic World

- Ships and Shipping

- Slave Codes

- Slave Names and Naming in the Anglophone Atlantic

- Slave Owners In The British Atlantic

- Slave Rebellions

- Slave Resistance in the Atlantic World

- Slave Trade and Natural Science, The

- Slave Trade, The Atlantic

- Slavery and Empire

- Slavery and Fear

- Slavery and Gender

- Slavery and the Family

- Slavery, Atlantic

- Slavery, Health, and Medicine

- Slavery in Africa

- Slavery in Brazil

- Slavery in British America

- Slavery in British and American Literature

- Slavery in Danish America

- Slavery in Dutch America and the West Indies

- Slavery in New England

- Slavery in North America, The Growth and Decline of

- Slavery in the Cape Colony, South Africa

- Slavery in the French Atlantic World

- Slavery, Native American

- Slavery, Public Memory and Heritage of

- Slavery, The Origins of

- Slavery, Urban

- Sociability in the British Atlantic

- Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts...

- South Atlantic

- South Atlantic Creole Archipelagos

- South Carolina

- Sovereignty and the Law

- Spain, Early Modern

- Spanish America After Independence, 1825-1900

- Spanish American Port Cities

- Spanish Atlantic World

- Spanish Colonization to 1650

- Subjecthood in the Atlantic World

- Sugar in the Atlantic World

- Swedish Atlantic World, The

- Technology, Inventing, and Patenting

- Textiles in the Atlantic World

- Texts, Printing, and the Book

- The American West

- The French Lesser Antilles

- The Fur Trade

- The Spanish Caribbean

- Time(scapes) in the Atlantic World

- Toleration in the Atlantic World

- Transatlantic Political Economy

- Tudor and Stuart Britain in the Wider World, 1485-1685

- Universities

- USA and Empire in the 19th Century

- Venezuela and the Atlantic World

- Visual Art and Representation

- War and Trade

- War of 1812

- War of the Spanish Succession

- Warfare in Spanish America

- Warfare in 17th-Century North America

- Warfare, Medicine, and Disease in the Atlantic World

- West Indian Economic Decline

- Whitefield, George

- Whiteness in the Atlantic World

- William Blackstone

- William Shakespeare, The Tempest (1611)

- William Wilberforce

- Witchcraft in the Atlantic World

- Women and the Law

- Women Prophets

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.148.24.167]

- 185.148.24.167

- By Time Period

- By Location

- Mission Statement

- Books and Documents

- Ask a NL Question

- How to Cite NL Heritage Website

- ____________

- Archival Mysteries

- Alien Enemies, 1914-1918

- Icefields Disaster

- Colony of Avalon

- Let's Teach About Women

- Silk Robes and Sou'westers

- First World War

- Première Guerre mondiale

- DNE Word Form Database

- Dialect Atlas of NL

- Partners List from Old Site

- Introduction

- Bibliography

- Works Cited

- Abbreviations

- First Edition Corrections

- Second Edition Preface

- Bibliography (supplement)

- Works Cited (supplement)

- Abbreviations (supplement)

- Documentary Video Series (English)

- Une série de documentaires (en français)

- Arts Videos

- Archival Videos

- Table of Contents

- En français

- Exploration and Settlement

- Government and Politics

- Indigenous Peoples

- Natural Environment

- Society and Culture

- Archives and Special Collections

- Ferryland and the Colony of Avalon

- Government House

- Mount Pearl Junior High School

- Registered Heritage Structures

- Stephenville Integrated High School Project

- Women's History Group Walking Tour

John Cabot's Voyage of 1497

There is very little precise contemporary information about the 1497 voyage. If Cabot kept a log, or made maps of his journey, they have disappeared. What we have as evidence is scanty: a few maps from the first part of the 16th century which appear to contain information obtained from Cabot, and some letters from non-participants reporting second-hand on what had occurred. As a result, there are many conflicting theories and opinions about what actually happened.

Cabot's ship was named the Matthew , almost certainly after his wife Mattea. It was a navicula , meaning a relatively small vessel, of 50 toneles - able to carry 50 tons of wine or other cargo. It was decked, with a high sterncastle and three masts. The two forward masts carried square mainsails to propel the vessel forward. The rear mast was rigged with a lateen sail running in the same direction as the keel, which helped the vessel sail into the wind.

There were about 20 people on board. Cabot, a Genoese barber(surgeon), a Burgundian, two Bristol merchants, and Bristol sailors. Whether any of Cabot's sons were members of the crew cannot be verified.

The Matthew left Bristol sometime in May, 1497. Some scholars think it was early in the month, others towards the end. It is generally agreed that he would have sailed down the Bristol Channel, across to Ireland, and then north along the west coast of Ireland before turning out to sea.

But how far north did he go? Again, it is impossible to be certain. All one can say is that Cabot's point of departure was somewhere between 51 and 54 degrees north latitude, with most modern scholars favouring a northerly location.

The next point of debate is how far Cabot might have drifted to the south during his crossing. Some scholars have argued that ocean currents and magnetic variations affecting his compass could have pulled Cabot far off course. Others think that Cabot could have held approximately to his latitude. In any event, some 35 days after leaving Bristol he sighted land, probably on 24 June. Where was the landfall?

Cabot was back in Bristol on 6 August, after a 15 day return crossing. This means that he explored the region for about a month. Where did he go?

Version française

Related Subjects

Share and print this article:.

Contact | © Copyright 1997 – 2024 Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Site, unless otherwise stated.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

John Cabot (Italian: Giovanni Caboto [dʒoˈvanni kaˈbɔːto]; c. 1450 - c. 1500) was an Italian navigator and explorer.His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII, King of England is the earliest known European exploration of coastal North America since the Norse visits to Vinland in the eleventh century. To mark the celebration of the 500th anniversary ...

John Cabot's Final Voyage. In London in late 1497, Cabot proposed to King Henry VII that he set out on another expedition across the north Atlantic. This time, ...

The Portuguese nobleman Vasco da Gama (1460-1524) sailed from Lisbon in 1497 on a mission to reach India and open a sea route from Europe to the East. After sailing down the western coast of ...

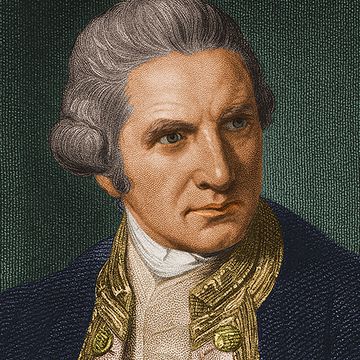

John Cabot, navigator and explorer who by his voyages in 1497 and 1498 helped lay the groundwork for the later British claim to Canada. His voyages were commissioned by England's King Henry VII, and the effect of Cabot's efforts was to reveal the viability of a short route across the North Atlantic.

Vasco da Gama (born c. 1460, Sines, Portugal—died December 24, 1524, Cochin, India) was a Portuguese navigator whose voyages to India (1497-99, 1502-03, 1524) opened up the sea route from western Europe to the East by way of the Cape of Good Hope. The famed bridge named in his honour in Lisbon, the Vasco da Gama Bridge that crosses over ...

John Cabot was a Venetian explorer and navigator known for his 1497 voyage to North America, where he claimed land in Canada for England. After setting sail in May 1498 for a return voyage to ...

Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) was a Portuguese navigator who, in 1497-9, sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa and arrived at Calicut (now Kozhikode) on the south-west coast of India.This was the first direct voyage from Portugal to India and allowed the Europeans to cut in on the immensely lucrative Eastern trade in spices.. Da Gama repeated his voyage in 1502-3, but this time ...

Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira (/ ˌ v æ s k u d ə ˈ ɡ ɑː m ə, ˈ ɡ æ m ə /; European Portuguese: [ˈvaʃku ðɐ ˈɣɐ̃mɐ]; c. 1460s - 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and the first European to reach India by sea.. His initial voyage to India by way of Cape of Good Hope (1497-1499) was the first to link Europe and Asia by an ocean route, connecting the ...

In 1497, explorer Vasco da Gama was commissioned by the Portuguese king to find a maritime route to the East. ... The crew reached India in just six months, and the voyage included a firefight ...

On his first voyage to India (1497-99), he traveled around the Cape of Good Hope with four ships, visiting trading cities in Mozambique and Kenya en route. Portugal's King Manuel I acted quickly to open trade routes with India, but a massacre of Portuguese in India caused him to dispatch a fleet of 20 ships in 1502, led by da Gama, to ...

The exact course of his 1497 voyage is the subject of much debate, but it is widely accepted that he landed on the coast of what is today known as Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island, claiming the land for the English crown. Significance of Cabot's voyage. Cabot's 1497 voyage was significant for several reasons. Firstly, it is believed to ...

Cabot's voyage in 1497 was likely undertaken with one ship, the Matthew of Bristol, accompanied by a crew of 18 to 20 men. The exact location of his landfall in North America remains a subject of debate among historians, with Cape Bonavista in Newfoundland and Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia among the leading contenders. Cabot's return to ...

Voyages Principal Voyage On 8 July 1497 Vasco da Gama sailed from Lisbon with a fleet of four ships with a crew of 170 men from Lisbon. Da Gama commanded the Sao Gabriel. Paulo da Gama - brother to Vasco - commanded the São Rafael, a three masted ship. There was also the caravel Berrio, and a storeship São Maria. Bartolomeu Dias also ...

John Cabot (aka Giovanni Caboto, c. 1450 - c. 1498 CE) was an Italian explorer who famously visited the eastern coast of Canada in 1497 CE and 1498 CE in his ship the Mathew (also spelt Matthew).Sponsored by Henry VII of England (r. 1485-1509 CE) to search for a sea route to Asia, Cabot's expeditions 'discovered' what the Italian called 'Newe Founde Launde'.

Second Voyage (1497) Cabot mounted a second attempt from Bristol in May 1497, using a ship called the Matthew. It may have been a happy coincidence that its name was the English version of Cabot's wife's name, Mattea. There are no records of the ship's individual crewmembers, and all the accounts of the voyage are second-hand — a ...

First English Voyage (1497) Giovanni Caboto (c. 1450-c. 1500) was a Venetian navigator and explorer. He was commissioned by King Henry VII in 1496 to sail for England, partly in hope of finding an alternate route to Asia, similar to Columbus. In 1497, John Cabot (as the English called him) sailed to Newfoundland.

Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot, b. c. 1450-d. c. 1500) was an Italian navigator credited to be the first European to set foot in North America after the Norse, during an expedition of 1497 carried out under the English flag. Little is known about his origins, although he certainly took up Venetian citizenship, implying origin elsewhere.

Over the years, the exact location of John Cabot's 1497 landfall has been a great subject of debate for scholars and historians. "Discovery of North America, by John and Sebastian Cabot" drawn by A.S. Warren for Ballou's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, April 7, 1855. From Charles de Volpi, Newfoundland: A pictorial Record (Sherbrooke, Quebec ...

Since the letter describes the 1497 voyage in considerable detail, while also throwing light on an earlier voyage from Bristol, it is regarded as the most important document find in this field to take place in the twentieth century. Despite the manifest importance of the John Day letter, it was apparent on reading Alwyn Ruddock's book proposal ...

The Voyages of John Cabot: Source: ... 1497. In 1497 he tried a second time, leaving Bristol in May and returning in August. This time he was successful, becoming the first European to find and describe North America since the Vikings. Unfortunately no records survive from this voyage, and all that is known about it comes from the reports of ...

IIn 1497, John Cabot (Giovanni Cabotto) set off on a voyage to Asia.On his way he, like Christopher Columbus, ran into an island off the coast of North America. As a result, Cabot became the second European to discover North America, thus laying an English claim which would be followed up only after an interval of over one hundred years.

to the 1497 voyage consisted of the four following letters: Lorenzo Pasqualigo to his brothers in Venice (August 23, 1497), Raimondo di Sancino to the Duke of Milan (August 24, and December 18, 1497), and Pedro de Ayala to the Catholic King (July 25, 1498).1 John Day's letter constitutes the fifth and most detailed report of the 1497 Cabot ...

Cabot's 14P7 Voyage to North America* The Matthew of Bristol is one of England's best known historic ships. For over 200 years, the Matthew has been ensconced in the popular imagination as the vessel in which John Cabot sailed on his 1497 voyage of discovery to North America. Since the construction ofa 'replica' of