Tourism in Indonesia

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Tourism in Indonesia is big business. But why is this industry so important and what does it all mean? Read on to find out…

Geography of Indonesia

The tourism industry in indonesia, statistics about tourism indonesia, popular tourist attractions in indonesia, types of tourism in indonesia, economic impacts of tourism in indonesia, social impacts of tourism in indonesia, environmental impacts of tourism in indonesia, faqs about tourism in indonesia , to conclude: tourism in indonesia.

Indonesia, an archipelago of over 17,000 islands, offers a mesmerising blend of cultures, landscapes, and historical wonders. Stretching from the bustling streets of Jakarta to the serene beaches of Bali and the ancient temples of Yogyakarta, Indonesia presents a unique tapestry of experiences for every traveller. In this article, I’ll provide insights into the diverse world of Indonesian tourism, capturing its vibrant traditions, natural beauty, and the myriad attractions that beckon visitors from around the globe. Join me as we embark on a journey through the multifaceted allure of Indonesia.

Indonesia is an archipelago located in Southeast Asia and is the world’s largest island country. Here is an overview of the geography of Indonesia:

- Location: Indonesia is situated between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, spanning both the Western and Eastern Hemispheres. It is located between mainland Southeast Asia and Australia.

- Archipelago: Indonesia consists of more than 17,000 islands, with five main islands: Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan (Borneo), Sulawesi, and Papua. These islands are surrounded by smaller islands and islets, forming a vast archipelago.

- Size and Borders: Indonesia covers a total land area of approximately 1.9 million square kilometers (736,000 square miles), making it the 14th largest country in the world by land area. It shares land borders with Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, and Timor-Leste.

- Mountains and Volcanoes: Indonesia is known for its stunning mountain ranges and active volcanoes. The highest peak is Puncak Jaya in Papua, standing at 4,884 meters (16,024 feet). Other notable mountains include Mount Bromo, Mount Rinjani, and Mount Merapi.

- Rivers and Lakes: Several rivers flow through Indonesia, including the Kapuas River in Kalimantan, the Musi River in Sumatra, and the Citarum River in Java. Lake Toba in North Sumatra is the largest volcanic lake in the world and a popular tourist destination.

- Biodiversity: Indonesia is incredibly rich in biodiversity, with diverse ecosystems such as rainforests, coral reefs, mangroves, and savannas. It is one of the world’s most biodiverse countries, home to numerous endemic species, including the Komodo dragon and orangutan.

- Climate: Indonesia experiences a tropical climate, characterized by high temperatures and humidity throughout the year. The country has two main seasons: the wet season (October to April) and the dry season (May to September).

- Coastal Areas: Indonesia has an extensive coastline that stretches for approximately 54,716 kilometers (34,000 miles). It is surrounded by the Indian Ocean to the west and south, and the Pacific Ocean to the north and east.

- Coral Reefs: Indonesia’s waters are renowned for their vibrant coral reefs, making it a popular destination for diving and snorkeling. The Coral Triangle, located in the waters surrounding Indonesia, is considered the world’s epicenter of marine biodiversity.

- Natural Hazards: Due to its location along the Pacific Ring of Fire, Indonesia is prone to earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and tsunamis. It is important for visitors to stay informed about any potential hazards and follow local authorities’ instructions.

The geography of Indonesia offers a diverse and picturesque landscape, from towering mountains to pristine beaches, making it a fascinating destination for nature enthusiasts and adventure seekers alike.

Indonesia is a country that attracts millions of tourists each year with its diverse culture, natural beauty, and rich history. The tourism industry in Indonesia plays a significant role in the country’s economy. Here is an introduction to the tourism industry in Indonesia:

Cultural Heritage: Indonesia is home to a vibrant mix of cultures, including Javanese, Balinese, Sumatran, and many more. Tourists are drawn to explore ancient temples, traditional dances, music performances, and local arts and crafts.

Natural Attractions: Indonesia boasts stunning natural landscapes, including pristine beaches, lush rainforests, active volcanoes, and diverse wildlife. Popular natural attractions include Bali’s beaches, Komodo National Park, Borobudur Temple, Mount Bromo, and the Togean Islands.

Adventure Tourism: Indonesia offers numerous opportunities for adventure tourism. Activities such as hiking, trekking, diving, surfing, and whitewater rafting are popular among tourists seeking thrilling experiences in destinations like Raja Ampat, Lombok, Yogyakarta, and Borneo.

Ecotourism: With its rich biodiversity and conservation efforts, Indonesia has become a hub for ecotourism. Travelers can explore national parks, wildlife reserves, and marine protected areas, contributing to sustainable practices and supporting local communities.

Culinary Experiences: Indonesian cuisine is diverse and flavorful, with regional specialties like nasi goreng, rendang, satay, and sambal. Food tourism is popular, and tourists can embark on culinary tours, cooking classes, and street food adventures.

Wellness and Spa Retreats: Indonesia offers a range of wellness and spa retreats, particularly in Bali. Tourists can indulge in traditional massages, yoga classes, meditation retreats, and wellness treatments set amidst serene natural surroundings.

Island Hopping: Indonesia’s vast archipelago provides opportunities for island hopping adventures. Travelers can explore different islands, each with its unique landscapes, cultures, and attractions. Popular island destinations include Bali, Lombok, Java, Sumatra, and the Gili Islands.

Heritage Sites: Indonesia is home to several UNESCO World Heritage Sites, such as Borobudur Temple, Prambanan Temple, Komodo National Park, and Ujung Kulon National Park. These sites attract history enthusiasts and cultural travelers.

Shopping and Souvenirs: Indonesia offers a range of shopping experiences, from bustling markets to modern shopping malls. Tourists can purchase traditional handicrafts, batik textiles, silver jewelry, wood carvings, and other unique souvenirs.

MICE Tourism: Indonesia has also gained prominence as a destination for Meetings, Incentives, Conferences, and Exhibitions (MICE) tourism. The country has modern convention centers and facilities that cater to business and corporate events.

The tourism industry in Indonesia continues to grow, offering a wide range of experiences and attractions for visitors. The government, along with tourism organizations, promotes sustainable tourism practices to preserve the country’s natural and cultural heritage while providing economic opportunities for local communities.

Now lets put things into perspective. Here are some statistics about tourism in Indonesia:

- Tourist Arrivals: In 2019, Indonesia welcomed over 16 million international tourist arrivals, making it one of the most visited countries in Southeast Asia.

- Contribution to GDP: Tourism contributes significantly to Indonesia’s economy, accounting for approximately 6% of the country’s GDP.

- Employment: The tourism sector in Indonesia provides employment opportunities to millions of people, both directly and indirectly. It is estimated that tourism supports around 13 million jobs in the country.

- Top Visitor Countries: The top five countries of origin for tourists visiting Indonesia are China, Malaysia, Australia, Singapore, and India.

- Popular Destinations: Bali is the most popular destination in Indonesia, attracting the majority of international tourists. Other popular destinations include Jakarta, Yogyakarta, Lombok, and Bandung.

- Cultural Tourism: Cultural tourism plays a significant role in Indonesia’s tourism industry. The country is home to numerous cultural attractions, including ancient temples, traditional dances, and unique arts and crafts.

- Ecotourism and Adventure Tourism: Indonesia is known for its diverse natural landscapes and offers opportunities for ecotourism and adventure tourism. Popular activities include diving, hiking, wildlife watching, and exploring national parks.

- Cruise Tourism: Indonesia has been focusing on developing cruise tourism, with several ports of call for cruise ships. Popular cruise routes include Bali, Komodo Island, and Raja Ampat.

- Domestic Tourism: Domestic tourism is also a significant contributor to the tourism industry in Indonesia. Indonesians travel within their own country to explore different regions and enjoy local attractions.

- Tourism Infrastructure: The Indonesian government has been investing in improving tourism infrastructure, including airports, roads, accommodations, and attractions, to enhance the visitor experience and support the industry’s growth.

These statistics highlight the importance of tourism in Indonesia’s economy and the country’s popularity as a tourist destination.

Indonesia offers a wide range of popular tourist attractions that cater to various interests. Here are some of the most renowned attractions in Indonesia:

- Bali: Known as the “Island of the Gods,” Bali is Indonesia’s most popular tourist destination. It offers stunning beaches, vibrant nightlife, lush rice terraces, ancient temples, and traditional arts and culture.

- Borobudur Temple: Located in Central Java, Borobudur Temple is the world’s largest Buddhist temple. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and attracts visitors with its intricate stone carvings and panoramic views of the surrounding landscapes.

- Komodo National Park: Situated in the eastern part of Indonesia, Komodo National Park is home to the Komodo dragon, the world’s largest lizard. Visitors can explore the park’s diverse marine life, hike to scenic viewpoints, and witness the unique reptiles in their natural habitat.

- Mount Bromo: Located in East Java, Mount Bromo is an active volcano and a popular destination for adventure seekers. The stunning sunrise views from its summit, the otherworldly landscape of the surrounding Bromo Tengger Semeru National Park, and the opportunity to hike and ride a jeep across the volcanic terrain make it a must-visit attraction.

- Ubud: Nestled in the heart of Bali, Ubud is known for its lush green landscapes, traditional art and crafts, and serene atmosphere. Visitors can explore art galleries, visit ancient temples, experience traditional Balinese dance performances, and enjoy the tranquility of the surrounding rice fields.

- Raja Ampat Islands: Located in West Papua, the Raja Ampat Islands are a paradise for diving enthusiasts. The region boasts stunning coral reefs, crystal-clear waters, and an abundance of marine life, including manta rays and colorful fish species.

- Tana Toraja: Situated in South Sulawesi, Tana Toraja is famous for its unique funeral rituals and traditional houses known as Tongkonan. Visitors can witness elaborate funeral ceremonies, explore traditional villages, and admire the intricate wood carvings that depict the local culture.

- Yogyakarta: Yogyakarta, often referred to as Jogja, is a cultural hub in Java. It is known for its ancient temples, including the UNESCO-listed Prambanan and the magnificent Borobudur. Visitors can also explore the royal palaces, visit art markets, and indulge in traditional Javanese cuisine.

- Gili Islands: The Gili Islands, located off the coast of Lombok, offer a tranquil escape with their pristine beaches, clear turquoise waters, and laid-back atmosphere. These islands are perfect for snorkeling, diving, and enjoying a relaxing beach vacation.

- Jakarta: As Indonesia’s capital city, Jakarta offers a blend of modern and traditional attractions. Visitors can explore historical sites such as Kota Tua (Old Town), visit museums, enjoy shopping in malls, and experience the vibrant city life.

These attractions showcase the diverse landscapes, rich cultural heritage, and natural beauty that make Indonesia a popular destination for travelers from around the world.

Indonesia offers a wide range of tourism experiences that cater to various interests. Here are some of the most popular types of tourism in Indonesia:

- Beach Tourism: With its thousands of islands, Indonesia is famous for its stunning beaches. Bali, Lombok, Gili Islands, and Raja Ampat are just a few of the many destinations that attract beach lovers with their pristine white sands, crystal-clear waters, and opportunities for snorkeling, diving, and water sports.

- Cultural Tourism: Indonesia is rich in cultural diversity, and cultural tourism is a major draw for visitors. Places like Yogyakarta, Solo, and Ubud in Bali offer insights into traditional arts, crafts, music, dance, and local customs. Visitors can witness traditional ceremonies, explore ancient temples, and immerse themselves in the unique cultures of different regions.

- Adventure Tourism: Indonesia’s diverse landscapes provide ample opportunities for adventure tourism. Hiking volcanoes, such as Mount Bromo or Mount Rinjani, trekking through lush jungles, white-water rafting, and surfing are popular activities for adventure enthusiasts. The country also offers opportunities for wildlife spotting, including orangutans in Borneo and Komodo dragons in Komodo National Park.

- Eco-Tourism: Indonesia’s rich biodiversity and natural wonders make it a prime destination for eco-tourism. Visitors can explore national parks like Taman Negara in Sumatra, explore the rainforests of Kalimantan, or venture into the remote areas of Papua to witness unique flora and fauna.

- Wellness and Spa Tourism: Indonesia is renowned for its wellness retreats and spa resorts. Places like Bali and Lombok offer a wide range of wellness experiences, including yoga retreats, meditation centers, traditional healing therapies, and luxurious spa treatments.

- Historical Tourism: Indonesia has a rich history dating back thousands of years, and historical tourism is popular among visitors. Sites like Borobudur Temple, Prambanan Temple, and Sultan’s Palace in Yogyakarta attract history enthusiasts who want to explore the country’s ancient past.

- Culinary Tourism: Indonesian cuisine is diverse and flavorful, making culinary tourism a popular choice. Visitors can indulge in local delicacies such as nasi goreng (fried rice), satay, rendang, and sate lilit. Exploring traditional food markets and taking cooking classes are also popular activities.

- Shopping Tourism: Indonesia offers a vibrant shopping scene, especially in cities like Jakarta and Bandung. Visitors can explore modern malls, traditional markets, and art markets to find unique handicrafts, batik textiles, traditional souvenirs, and fashionable items.

- Religious Tourism: Indonesia is home to various religions, and religious tourism is prominent. From visiting the iconic Borobudur Temple and Prambanan Temple for Buddhist and Hindu pilgrimages to exploring mosques and historic churches, there are religious sites that attract visitors of all faiths.

- Diving and Snorkeling Tourism: Indonesia is part of the Coral Triangle, which is known for its rich marine biodiversity. Diving and snorkeling enthusiasts flock to destinations like Bali, Komodo National Park, Raja Ampat, and the Gili Islands to explore vibrant coral reefs, encounter colorful fish species, and witness manta rays and sea turtles.

These types of tourism showcase the diverse offerings of Indonesia, attracting travelers with varying interests and preferences.

Tourism plays a significant role in the economy of Indonesia, contributing to its GDP, employment, and foreign exchange earnings. Here are some key economic impacts of tourism in Indonesia:

- GDP Contribution: Tourism makes a substantial contribution to Indonesia’s GDP. In 2019, the direct contribution of travel and tourism to the country’s GDP was approximately 5.2%. When considering the indirect and induced impacts, the total contribution of tourism to the GDP was estimated to be around 11.8%.

- Employment Generation: Tourism is a major job creator in Indonesia. The industry provides employment opportunities for various sectors, including hotels, restaurants, transportation, tour operators, travel agencies, and handicrafts. In 2019, travel and tourism supported about 13.8 million jobs, accounting for approximately 10% of total employment in the country.

- Foreign Exchange Earnings: Tourism brings in significant foreign exchange earnings to Indonesia. In 2019, international tourism receipts amounted to around $20.7 billion. This revenue helps improve the country’s balance of payments, supports the local currency, and contributes to economic stability.

- Regional Development: Tourism helps in the development of various regions in Indonesia. Popular tourist destinations, such as Bali, Yogyakarta, and Lombok, receive substantial investments in infrastructure, accommodation, and services. This development spreads economic benefits beyond major cities and contributes to the growth of local economies.

- Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): Tourism provides opportunities for small and medium-sized enterprises to thrive. Local businesses, such as homestays, restaurants, handicraft producers, and tour operators, benefit from the demand generated by tourists. This promotes entrepreneurship, empowers local communities, and supports sustainable economic growth.

- Infrastructure Development: The growth of tourism in Indonesia has led to infrastructure development. Airports, roads, ports, and other transportation facilities have been expanded and improved to accommodate the increasing number of tourists. This infrastructure development not only enhances the tourism experience but also benefits other sectors of the economy.

- Investment Opportunities: The tourism industry attracts both domestic and foreign investments, driving economic growth and diversification. Investments are made in hotels, resorts, entertainment facilities, eco-tourism projects, and transportation infrastructure. These investments create employment opportunities, generate revenue, and stimulate economic activities in the related sectors.

- Income Distribution: Tourism in Indonesia contributes to income distribution by generating employment and income opportunities for local communities. Revenue generated from tourism activities can have a multiplier effect, as it circulates within the local economy through spending on goods and services. This helps improve the standard of living and reduces income inequalities.

- Cultural Preservation: Tourism in Indonesia often promotes the preservation of cultural heritage and traditional practices. Communities with unique cultural attractions benefit from tourism, as it encourages the preservation and promotion of their customs, arts, crafts, and traditional performances. This not only helps sustain cultural identity but also provides economic incentives for cultural preservation efforts.

- Diversification of Economy: The tourism industry contributes to the diversification of Indonesia’s economy. It reduces dependence on specific sectors and creates alternative sources of income. This diversification strengthens the overall resilience of the economy and reduces vulnerability to external shocks.

It is important to note that the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted the tourism industry worldwide, including Indonesia. The full extent of its impact on the economic contributions of tourism in Indonesia is still being assessed, and recovery efforts are underway to revive the sector.

Tourism in Indonesia has several social impacts that influence local communities, cultural preservation, and social dynamics. Here are some key social impacts of tourism in Indonesia:

- Cultural Exchange: Tourism in Indonesia facilitates cultural exchange between visitors and local communities. Tourists have the opportunity to experience Indonesia’s rich cultural heritage, traditions, and customs. This interaction fosters mutual understanding, appreciation, and respect for diverse cultures.

- Preservation of Cultural Heritage: Tourism in Indonesia often plays a vital role in preserving cultural heritage. Popular tourist destinations in Indonesia, such as Borobudur Temple, Prambanan Temple, and traditional villages, receive conservation efforts and financial support due to their cultural significance. Tourism revenue helps maintain and protect cultural sites, arts, crafts, and traditional practices.

- Community Empowerment: Tourism in Indonesia provides income and employment opportunities for local communities. Small-scale businesses, homestays, local guides, and artisans benefit from the demand created by tourists. This economic empowerment enhances the quality of life, improves infrastructure, and supports community development initiatives.

- Awareness of Environmental Conservation: Tourism in Indonesia can raise awareness about environmental conservation. Many tourist attractions in Indonesia are natural wonders, such as Komodo National Park, Taman Negara Gunung Leuser, and Raja Ampat. Visitors, through guided tours and educational programs, learn about the importance of preserving natural resources, ecosystems, and wildlife habitats.

- Infrastructure Development: Tourism development often leads to improved infrastructure in local communities. Airports, roads, accommodations, and public facilities are upgraded to cater to the needs of tourists. This infrastructure development benefits not only tourists but also local residents, improving their access to services and enhancing their overall living conditions.

- Cultural Revitalization: Tourism in Indonesia can contribute to the revitalization of traditional cultural practices. Local communities may revive traditional dances, music, handicrafts, and rituals to showcase their cultural heritage to visitors. This revitalization helps preserve and promote cultural traditions that may have otherwise declined over time.

- Education and Awareness: Tourism provides educational opportunities for local communities. Visitors often show interest in learning about the local culture, history, and traditions. This encourages local communities to share their knowledge and traditions, leading to the preservation and transmission of cultural knowledge across generations.

- Pride in Local Identity: Tourism in Indonesia can instill a sense of pride in local communities. Recognizing the value and appeal of their own cultural heritage, communities may take pride in preserving and showcasing their traditions, resulting in increased self-esteem and cultural identity.

- Social Integration: Tourism in Indonesia can foster social integration by bringing together people from different backgrounds. Visitors and locals interact, exchange ideas, and share experiences, contributing to social cohesion and understanding.

- Community-Based Tourism Initiatives: Community-based tourism initiatives empower local communities to participate actively in tourism development. These initiatives ensure that the benefits of tourism are distributed more equitably, allowing communities to have a voice in decision-making, preserving their cultural heritage, and maintaining control over their resources.

While tourism in Indonesia brings numerous social benefits, it is important to manage its impacts responsibly to avoid negative social consequences such as over-commercialization, cultural commodification, and social inequalities. Sustainable tourism practices that involve local communities and respect their traditions and values are crucial for maximizing the positive social impacts of tourism in Indonesia.

Tourism in Indonesia, like in many other countries, has both positive and negative environmental impacts. Here are some key environmental impacts of tourism in Indonesia:

- Natural Resource Consumption: Tourism in Indonesia places demands on natural resources such as water, energy, and land. Increased tourist arrivals often lead to higher water consumption, increased energy usage for accommodation and transportation, and land development for hotels, resorts, and infrastructure. This can strain local resources and put pressure on ecosystems.

- Waste Generation: The tourism industry generates significant amounts of waste, including plastic, packaging, food waste, and other disposable items. Improper waste management and disposal practices can lead to pollution of water bodies, soil, and air, impacting the natural environment and ecosystems.

- Loss of Biodiversity and Habitat Degradation: Popular tourist destinations in Indonesia often include natural areas, such as rainforests, coral reefs, and marine ecosystems. Increased tourism activities can lead to habitat destruction, deforestation, and loss of biodiversity. Unsustainable practices like overfishing, improper waste disposal, and unregulated development can degrade natural habitats and harm wildlife populations.

- Pollution and Carbon Emissions: Tourism-related activities contribute to pollution, including air and water pollution. Transportation, especially air travel, generates greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change. Water pollution can occur through wastewater discharge from accommodations and recreational activities, impacting marine ecosystems and coral reefs.

- Deforestation and Land Conversion: Tourism development can lead to deforestation and land conversion for hotels, resorts, and infrastructure projects. This can result in the loss of valuable forest ecosystems, disrupt wildlife habitats, and contribute to soil erosion and land degradation.

- Coral Reef Damage: Indonesia is known for its stunning coral reefs, which attract divers and snorkelers. However, irresponsible diving practices, anchoring, and the use of harmful chemicals for sunscreen can cause damage to coral reefs, affecting their health and biodiversity.

- Water and Coastal Erosion: Increased tourism activities and infrastructure development along coastlines can contribute to water erosion and coastal degradation. Beach erosion, loss of sand dunes, and alteration of natural sediment patterns can impact coastal ecosystems and diminish the aesthetic value of the area.

- Water Pollution from Tourism Activities: Recreational activities such as boating, swimming, and snorkeling can introduce pollutants into water bodies, including oil spills, sewage discharge, and litter. These pollutants can harm aquatic life, coral reefs, and water quality.

- Pressure on Protected Areas: Indonesia has many protected areas, including national parks and reserves. High visitor numbers and inadequate management can result in increased pressure on these fragile ecosystems, leading to habitat disturbance and wildlife stress.

- Cultural and Heritage Impact: Increased tourism can put pressure on cultural and heritage sites, leading to overcrowding, erosion of traditional practices, and loss of authenticity. Uncontrolled tourism development can disrupt local communities and their way of life.

It’s important to note that many efforts are being made in Indonesia to promote sustainable tourism practices and minimize the negative environmental impacts of tourism in Indonesia. This includes implementing waste management programs, promoting eco-friendly accommodations, educating tourists about responsible behavior, and supporting conservation initiatives. Responsible tourism practices and awareness are essential for protecting Indonesia’s diverse ecosystems and preserving its natural beauty for future generations.

Now that we know a bit more about tourism in Indonesia, lets answer some of the most common questions on this topic:

Sure! Here are 10 frequently asked questions about tourism in Indonesia along with their answers:

What is the best time to visit Indonesia?

The best time to visit Indonesia is during the dry season, which generally falls between April and October. However, the specific ideal time to visit may vary depending on the region you plan to explore.

What are the must-visit destinations in Indonesia?

Some popular destinations in Indonesia include Bali, Jakarta, Yogyakarta, Komodo National Park, Borobudur Temple, Mount Bromo, and Raja Ampat.

Do I need a visa to visit Indonesia?

It depends on your nationality. Many countries are eligible for visa-free entry or visa on arrival, allowing visitors to stay for a certain period. However, some nationalities may require a visa in advance. It’s recommended to check the visa requirements for your specific nationality before traveling.

What is the currency of Indonesia?

The currency of Indonesia is the Indonesian Rupiah (IDR). It’s advisable to carry local currency for convenience, although major tourist areas also accept major credit cards.

Is it safe to travel in Indonesia?

Overall, Indonesia is considered a safe destination for tourists. However, it’s always important to take general safety precautions, such as being aware of your surroundings, avoiding isolated areas at night, and taking necessary precautions against theft.

What are some traditional Indonesian dishes I should try?

Some popular Indonesian dishes to try include nasi goreng (fried rice), satay, rendang (spicy beef stew), gado-gado (vegetable salad with peanut sauce), and nasi padang (rice with various side dishes).

Is it necessary to get vaccinations before traveling to Indonesia?

It’s recommended to consult with a healthcare professional or travel clinic to get the necessary vaccinations and medical advice based on your travel plans and personal health history. Common vaccinations include Hepatitis A, Typhoid, and Tetanus.

Can I drink tap water in Indonesia?

It’s generally advisable to drink bottled or filtered water in Indonesia to avoid any potential health risks. Bottled water is widely available and affordable.

Are there any cultural customs or etiquette I should be aware of?

Indonesian culture values politeness and respect. It’s advisable to dress modestly, especially when visiting religious sites, and to ask for permission before taking someone’s photo. Learning a few basic Indonesian phrases can also be appreciated by the locals.

What are some popular water activities in Indonesia?

Indonesia offers various water activities such as snorkeling, scuba diving, surfing, and island hopping. Popular spots include Bali, Gili Islands, and Komodo National Park.

Indonesia’s rich tapestry of islands offers a captivating blend of cultures, landscapes, and historical wonders. From the bustling streets of Jakarta to the serene beaches of Bali, the archipelago promises diverse and unforgettable experiences. If you enjoyed this article, I am sure you will like these too:

- 25 Fun Facts About Indonesia

- 30 Fun Facts About Vietnam

- Tourism in Bali- From Islands to Temples

- What is a volcanic crater? Made SIMPLE

- 26 Fun Facts About Crustaceans

Liked this article? Click to share!

Travel, Tourism & Hospitality

Travel and tourism in Indonesia - statistics & facts

Indonesia as a global tourism destination, indonesian tourism: on the road to recovery, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Contribution of the tourism industry to GDP Indonesia 2016-2021

Number of international visitor arrivals Indonesia 2014-2023

Value of international tourism receipts Indonesia 2011-2020

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Current statistics on this topic.

Number of foreign tourist arrivals to Bali, Indonesia 2008-2023

Average length of stay of inbound visitors to Indonesia 2012-2021

Related topics

Recommended.

- Accommodation in Indonesia

- Aviation industry in Indonesia

- Passenger transport in Indonesia

- Demographics of Indonesia

- Natural disasters in Indonesia

Recommended statistics

- Basic Statistic Number of international tourist arrivals worldwide 2005-2023, by region

- Premium Statistic International tourist arrivals worldwide 2019-2022, by subregion

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism contribution share to GDP in Indonesia 2019-2021

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism contribution to GDP in Indonesia 2019-2021

- Premium Statistic Absolute economic contribution of tourism in Indonesia 2014-2029

Number of international tourist arrivals worldwide 2005-2023, by region

Number of international tourist arrivals worldwide from 2005 to 2023, by region (in millions)

International tourist arrivals worldwide 2019-2022, by subregion

Number of international tourist arrivals worldwide from 2019 to 2022, by subregion (in millions)

Travel and tourism contribution share to GDP in Indonesia 2019-2021

Contribution of travel and tourism sector to GDP in Indonesia from 2019 to 2021

Travel and tourism contribution to GDP in Indonesia 2019-2021

Contribution of travel and tourism sector to GDP in Indonesia from 2019 to 2021 (in trillion Indonesian rupiah)

Absolute economic contribution of tourism in Indonesia 2014-2029

Absolute economic contribution of tourism in Indonesia from 2014 to 2029 (in million U.S. dollars)

Inbound tourism

- Premium Statistic Number of international visitor arrivals Indonesia 2014-2023

- Premium Statistic Number of international visitor arrivals from Asia Pacific to Indonesia 2014-2023

- Premium Statistic Number of international visitor arrivals Indonesia 2022, by mode of transport

- Premium Statistic Number of foreign visitor arrivals in Indonesia 2022, by port of entry

- Premium Statistic Monthly international air passengers at Soekarno-Hatta airport Indonesia 2019-2023

- Premium Statistic Average length of stay of inbound visitors to Indonesia 2012-2021

Number of international visitor arrivals in Indonesia from 2014 to 2023 (in millions)

Number of international visitor arrivals from Asia Pacific to Indonesia 2014-2023

Number of international visitor arrivals from Asia Pacific to Indonesia from 2014 to 2023 (in millions)

Number of international visitor arrivals Indonesia 2022, by mode of transport

Number of international visitor arrivals in Indonesia in 2022, by mode of transport (in 1,000s)

Number of foreign visitor arrivals in Indonesia 2022, by port of entry

Number of foreign visitor arrivals in Indonesia 2022, by main port of entries (in 1,000s)

Monthly international air passengers at Soekarno-Hatta airport Indonesia 2019-2023

Number of monthly international air passengers at Soekarno-Hatta Airport (CGK) in Indonesia from January 2019 to December 2023 (in 1,000s)

Average length of stay of inbound visitors to Indonesia from 2012 to 2021 (by number of days)

Domestic tourism

- Premium Statistic Number of domestic trips Indonesia 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of domestic trips made in Indonesia 2021, by mode of transport

- Premium Statistic Breakdown of domestic trips in Indonesia 2021, by purpose

- Premium Statistic Monthly domestic air passengers at Soekarno-Hatta airport Indonesia 2019-2023

- Premium Statistic Number of domestic guests in star hotels Indonesia 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Average length of stay in hotels by domestic travelers in Indonesia 2012-2021

- Premium Statistic Common concerns about traveling Indonesia 2023

Number of domestic trips Indonesia 2013-2022

Total number of domestic trips in Indonesia from 2013 to 2022 (in millions)

Number of domestic trips made in Indonesia 2021, by mode of transport

Number of domestic trips made in Indonesia in 2021, by mode of transport (in millions)

Breakdown of domestic trips in Indonesia 2021, by purpose

Number of domestic trips made in Indonesia in 2021, by purpose of travel (in millions)

Monthly domestic air passengers at Soekarno-Hatta airport Indonesia 2019-2023

Number of monthly domestic air passengers at Soekarno-Hatta Airport (CGK) in Indonesia from January 2019 to June 2023 (in millions)

Number of domestic guests in star hotels Indonesia 2013-2022

Total number of domestic guests in star hotels in Indonesia from 2013 to 2022 (in millions)

Average length of stay in hotels by domestic travelers in Indonesia 2012-2021

Average length of stay in hotels by domestic travelers in Indonesia from 2012 to 2021 (by number of nights)

Common concerns about traveling Indonesia 2023

Most common concerns about traveling among tourists in Indonesia as of January 2023

Economic impact

- Premium Statistic Average daily expenditure of inbound visitors to Indonesia 2012-2021

- Premium Statistic Inbound tourism expenditure value Indonesia 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Value of international tourism receipts Indonesia 2011-2020

- Premium Statistic Number of employees in tourism industry Indonesia 2011-2020

Average daily expenditure of inbound visitors to Indonesia 2012-2021

Average daily expenditure of inbound visitors to Indonesia from 2012 to 2021 (in U.S. dollars)

Inbound tourism expenditure value Indonesia 2013-2022

Value of inbound tourism expenditure in Indonesia from 2013 to 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars)

International tourism receipts in Indonesia from 2011 to 2020 (in million U.S. dollars)

Number of employees in tourism industry Indonesia 2011-2020

Number of employees in the tourism industry in Indonesia from 2011 to 2020 (in 1,000s)

Accommodations, hotels, and bookings

- Premium Statistic Number of accommodation establishments for visitors Indonesia 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of hotels and similar establishments Indonesia 2012-2021

- Premium Statistic Total number of hotels by star ratings Indonesia 2023

- Premium Statistic Number of employees in accommodation services for visitors Indonesia 2011-2020

- Premium Statistic Occupancy rate in classified hotels in Indonesia 2013-2022

- Premium Statistic Leading online travel agencies used in Indonesia 2023

- Premium Statistic Preferred accommodation booking methods for year-end holiday Indonesia 2022

Number of accommodation establishments for visitors Indonesia 2013-2022

Number of accommodation establishments for visitors in Indonesia from 2013 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Number of hotels and similar establishments Indonesia 2012-2021

Number of hotels and similar establishments in Indonesia from 2012 to 2021 (in 1,000s)

Total number of hotels by star ratings Indonesia 2023

Total number of hotels in Indonesia in 2023, by star ratings

Number of employees in accommodation services for visitors Indonesia 2011-2020

Number of employees in hotels and similar establishments in Indonesia from 2011 to 2020 (in 1,000s)

Occupancy rate in classified hotels in Indonesia 2013-2022

Room occupancy rate of classified hotels in Indonesia from 2013 to 2022

Leading online travel agencies used in Indonesia 2023

Most popular online travel agencies among consumers in Indonesia as of June 2023

Preferred accommodation booking methods for year-end holiday Indonesia 2022

Most preferred accommodation booking methods for year-end holiday travel in Indonesia as of November 2022

Impact of COVID-19 on tourism

- Premium Statistic Quarterly change in international tourism receipts COVID-19 in Indonesia 2022

- Premium Statistic Monthly number of international visitor arrivals Indonesia 2020-2023

- Premium Statistic International tourism receipts during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia Q4 2022

- Premium Statistic Monthly change in international tourist arrivals due to COVID-19 Indonesia 2020-2022

Quarterly change in international tourism receipts COVID-19 in Indonesia 2022

Quarterly change in international tourism receipts during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Indonesia in 2022

Monthly number of international visitor arrivals Indonesia 2020-2023

Number of international visitor arrivals in Indonesia from January 2020 to March 2023 (in 1,000s)

International tourism receipts during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia Q4 2022

International tourism receipts during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Indonesia as of 4th quarter in 2022 (in thousand U.S. dollars)

Monthly change in international tourist arrivals due to COVID-19 Indonesia 2020-2022

Monthly change in international tourist arrivals during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Indonesia as of December 2022

Further reports Get the best reports to understand your industry

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

share this!

May 12, 2021

High-end tourism in Indonesia fails to empower local people during pandemic

by Chloe King, The Conversation

The COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc on the travel and tourism industry globally. Indonesia is no exception.

The tourism industry in the country with the fourth-largest population in the world has slowed down during the pandemic.

Foreign arrivals dropped by 75% from 16.11 million in 2019 to just 4.02 million in 2020 . This was a hard blow to a tourism economy that supplied 5.7% of the country's gross domestic product and provided 12.6 million jobs in 2019 .

To revive the industry, the Indonesian government has launched a new approach to promote high-end tourism .

High-end tourism is meant to combat the often unsustainable growth in mass tourism. It attracts fewer tourists who spend more on luxury trips than typical mass tourism experiences. In theory, this reduces environmental impacts while increasing economic benefits .

Our latest research in Wakatobi National Park, an area of immense marine biodiversity spread across four main islands in Southeast Sulawesi province, demonstrates the limitations of high-end tourism development.

While it may offer some conservation benefits, its inherently high price tag means it caters to the most privileged sectors of society, while the local political elite accrue the profits.

Tourism development must do more to focus on providing benefits for communities beyond just financial gains. It should support local communities to increase their skills and knowledge to equip them to be resilient to crises and economic shocks.

Unsustainable travel experiences

Our six-month research effort compared high-end, volunteer-based and community-based tourism operating in the marine-rich Wakatobi National Park. The aim was to see which form of tourism development best equipped communities to respond to crises like COVID-19.

Wakatobi National Park is part of a government initiative to develop "high-quality" tourism destinations across the country through its so-called "10 New Balis" program. This effort aims to accelerate tourism development in 10 new destinations beyond the country's top tourist destination, Bali.

According to interviews with the regional tourism office in Wakatobi, the local government has set a goal of increasing visitor numbers from 20,000 to 100,000 by 2025 by focusing on high-end tourism development.

Wakatobi National Park was designated as a national park in 1996 and covers an area of 13,900 square kilometers. The park has two foreign-owned dive operators on the islands of Tomia and Hoga, with local homestay operators proliferating throughout the park.

A high-end dive operator in the national park offered a valuable case study in exemplifying how exclusive and expensive tourism development has left communities less resilient and ill-prepared to face a crisis.

Guests pay between US$300 and US$1,000 per person for a single night stay. The operator is able to use these fees to pay each village around Tomia (17 in total) between Rp 1.25 and 7 million (about US$85-475) each month in exchange for halting destructive fishing practices and avoiding fishing on 30 kilometers of reef, including a no-take zone. Local dive operators cannot take guests on or near the resort's reef.

While this has significantly protected and improved natural resources and financial capital, local fishers and dive operators alike lost agency and ability to use the reefs.

Additionally, other respondents noted that the payments did not reach the community directly. The Badan Permusyawaratan Desa (BPD), considered the "parliament" of local villages in Indonesia's new era of regional autonomy, controls the money.

Respondents felt they did not have a say in how the BPD spends the money it receives from the high-end dive operators.

Respondents alleged it benefited the local "political elite" in the BPD as the politicians spend the money based on "their will, not the will of society."

"What [the high-end operator] does is right, with their regulations and money, but they have a greater responsibility to society. Society does not need the money, we need the skills. If they just give money, it will only benefit the political elite," one respondent said.

Due to the exclusive and closed-off nature of the resort, guests rarely interact with the local community. This was frequently cited as a point of frustration.

Intercultural exchange and informal interaction facilitated through home-stay operators help to increase human capital and community skills. With high-end resorts, this interaction is rare.

Furthermore, no local people from the national park had been trained as dive guides during the 25 years the foreign operator was in business. Few respondents were able to identify opportunities for upward mobility and skills training for local staff.

Such tourism development is reminiscent of colonialist structures that pervade Indonesia to this day, through the acquiescence of rural elites to extract profits and control resources, whether through exploitation or today's modern modes of conservation.

Tourism for all

High-end dive tourism models, where marine reserves are privately financed and enforced, may have led to critical and obvious gains in marine biodiversity and conservation success.

Misool in Raja Ampat, in the most eastern island of Indonesia, is another example of an area that has seen substantial biodiversity benefits . The total biomass of the marine reserve increased by 250% over just six years due to a similar luxury tourism model.

However, for whom are these resources being conserved? What is being made to be resilient, and why? Suppose the answer is to drive future tourism growth, limited to those wealthy enough to provide and access such "high-quality" tourism experiences. In that case, we must return to view the crisis at hand.

With tourism at a standstill for more than a year, local communities have been left to face the consequences without opportunities to increase their skills and knowledge, which would have helped ensure their resilience to such a crisis.

Emerging into a post-COVID-19 landscape, where climate change threats loom large in the communities where tourism once boomed, tourism must first and foremost be developed with local communities in mind.

As one respondent said in a focus group discussion: "[People from capital] Jakarta wants to develop only high-end tourism, but I don't agree. Tourism should be for everyone to come, not just the rich."

Provided by The Conversation

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Research team discovers more than 50 potentially new deep-sea species in one of the most unexplored areas of the planet

5 hours ago

New study details how starving cells hijack protein transport stations

New species of ant found pottering under the Pilbara named after Voldemort

6 hours ago

Searching for new asymmetry between matter and antimatter

Where have all the right whales gone? Researchers map population density to make predictions

7 hours ago

Exoplanets true to size: New model calculations shows impact of star's brightness and magnetic activity

8 hours ago

Decoding the language of cells: Profiling the proteins behind cellular organelle communication

A new type of seismic sensor to detect moonquakes

Macroalgae genetics study sheds light on how seaweed became multicellular

Africa's iconic flamingos threatened by rising lake levels, study shows

Relevant physicsforums posts, biographies, history, personal accounts.

2 hours ago

Who is your favorite Jazz musician and what is your favorite song?

14 hours ago

Cover songs versus the original track, which ones are better?

21 hours ago

For WW2 buffs!

22 hours ago

Which ancient civilizations are you most interested in?

Apr 11, 2024

Etymology of a Curse Word

More from Art, Music, History, and Linguistics

Related Stories

Frog cakes and Fruchocs: Famous local foods attract valuable tourist dollars

Mar 5, 2021

Nature conservation and tourism can coexist despite conflicts

Sep 21, 2020

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mammals at tourist destinations

Mar 3, 2021

What COVID-19 can teach tourism about the climate crisis

Jul 15, 2020

Ecotourism transforms attitudes to marine conservation

May 5, 2020

Tourism desperately wants a return to the 'old normal' but that would be a disaster

Feb 19, 2021

Recommended for you

Building footprints could help identify neighborhood sociodemographic traits

Apr 10, 2024

Are the world's cultures growing apart?

First languages of North America traced back to two very different language groups from Siberia

Apr 9, 2024

Can the bias in algorithms help us see our own?

Public transit agencies may need to adapt to the rise of remote work, says new study

The 'Iron Pipeline': Is Interstate 95 the connection for moving guns up and down the East Coast?

Let us know if there is a problem with our content.

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

Technology can bring more tourists back to Indonesia – but first we need a map to guide us

Interaction Designer, University of Technology Sydney

Disclosure statement

Ainnoun Kornita terafiliasi dengan Kementerian Pariwisata dan Ekonomi Kreatif. Saya bekerja di organisasi tersebut.

University of Technology Sydney provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic hit the world and has been devastating for human life. Global tourism collapsed as tourist arrivals decreased by 71% in 2021 .

That has had a significant impact in countries like Indonesia, where tourism was booming pre-pandemic : tourism generated Rp536.8 trillion in 2017 , or 4.1% of Indonesia’s total gross domestic product, with 12.7 million jobs in the industry.

However, digital technology adoption has been an unexpected silver lining of the pandemic, emerging as a tool that can help accelerate tourism recovery worldwide. It shifts tourist preferences and priorities towards digital travel. It also presents new business opportunities in offering more relevant online experiences.

More tourism activities now offer hybrid events, particularly for music festivals, concerts and business meetings. Virtual reality and augmented reality (VR/AR) provide a new travel experience, and have been adopted by hotels, destinations and online travel marketplaces all over the globe.

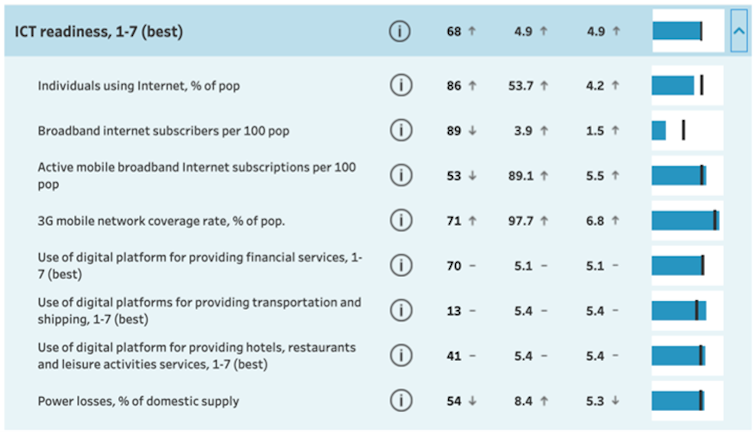

There is, however, a challenge in technology adoption to support tourism in Indonesia: its comparatively low information and communication technology (ICT) readiness.

According to a May 2022 World Economic Forum report, Indonesia was ranked 68th in 2020 in its ICT readiness. This ranking was based on the expansion of individual internet usage and 3G mobile broadband network coverage in each country.

While Indonesia’s ranking had slightly increased from 70th in 2019, it was behind Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam.

The use of digital platforms for financial services, transportation and shipping and leisure activities in Indonesia are slow, and should be a subject for improvement.

From dreaming to sharing, tech can help tourists

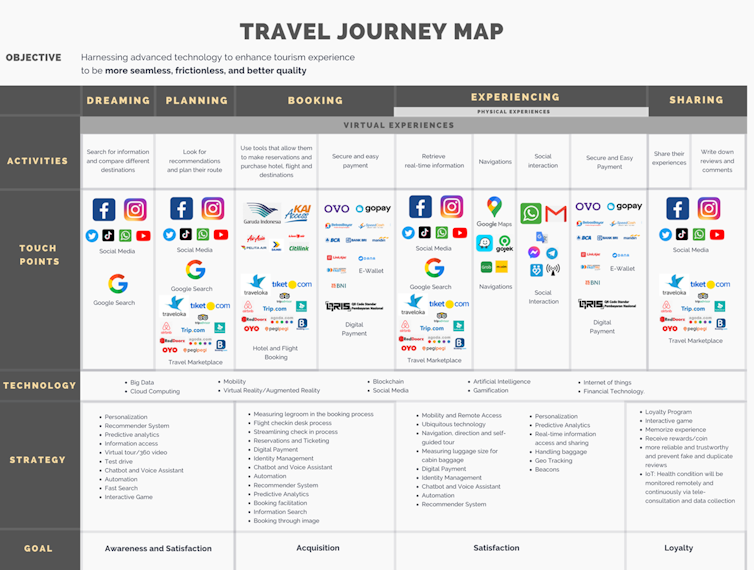

One study emphasises how technology needs to be a catalyst to create meaningful tourism experiences.

The tourist experience is the backbone of business success, as it drives people to make travel decisions.

The key to enhancing this experience is understanding how tourists make travel decisions through different travel stages: from dreaming, planning, booking, and experiencing, to sharing.

Using technology to improve the tourism experience throughout all travel stages is critical. Technology helps connect tourism supply and demand, creating physical and virtual experiences. It enables tourism providers to maintain competitiveness in the market. Tourists also use technology to plan their trips, experience destinations and reflect on their travels to obtain satisfaction.

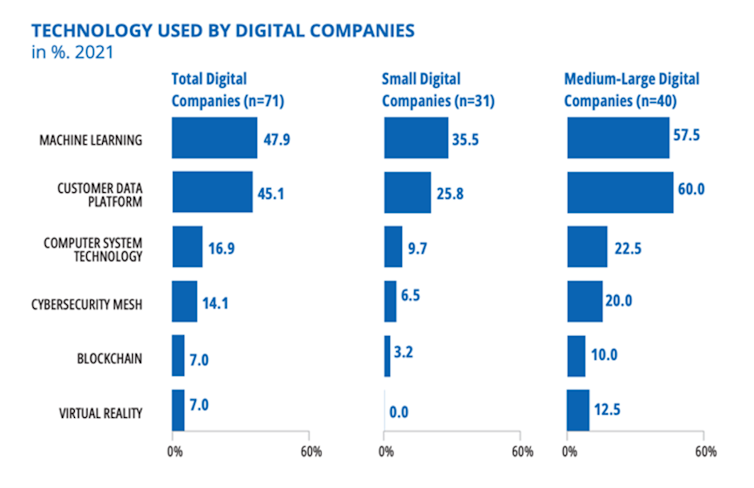

Several technologies that shape the tourism experience include Big Data , cloud computing , VR/AR, blockchain, artificial intelligence, social media, gamification and the internet of things .

For example, the Skyscanner chatbot on Facebook or Whatsapp assists with travelling needs, from digging out information to offering fast responses during the booking process. In another example, Iceland has upgraded Keflavik Airport’s automated baggage tracking system to alert travellers when their baggage is nearby.

Advanced technology creates value throughout tourism experiences by providing choices and convenience, flexibility, safety, fun and enjoyment, and real-time, reliable information. As a result, tourists have more options and flexibility in every stage of their travel journey: from acquiring information, planning an e-itinerary, booking and purchasing flights or hotels online, to sharing their experiences.

Opportunities and challenges for Indonesia

Indonesia has a large population, growing mobile internet penetration and a vibrant start-up ecosystem, with the most growth recorded in e-commerce and online transportation. All of those factors demonstrate Indonesia’s potential for adopting advanced technology.

But Indonesia must also catch up to other countries in capturing its digital potential. The inequality of ICT infrastructure between regions and income classes has become the main barrier to the accessibility of good quality internet.

Moreover, digital literacy – especially on safety – is low and needs improvement .

A World Bank report shows digital payment adoption is relatively low, with 50% of Indonesian online buyers preferring to pay cash on delivery.

The lack of awareness, knowledge and trust, regulation and appropriate infrastructure curb e-commerce growth in Indonesia.

Such conditions could hinder the success of the Indonesian tourism industry, as it needs to maintain competitiveness amid growing digital demands. Without advanced technology, the tourism industry will not thrive in the ever-changing global market.

A map for the future

The Indonesian government needs a map to design digital strategies that match with tourists’ expectations and needs. The map would present tourists’ experiences, including their interactions with the most relevant digital touchpoint in every travel stage (from dreaming to sharing).

Such a map could address digital tourism challenges, and help the tourism industry offer a frictionless, seamless, and better-quality tourism experience.

The map could also raise awareness among tourism stakeholders about the current digital technology in Indonesia and tourism in particular.

Areas that the Indonesian government could focus on to provide the best digital services include:

- improving digital government services in the tourism sector

- utilising digital strategies for promoting tourism

- adopting data integration and interoperability in the tourism sector

- investing in digital literacy for tourism industry workers

- more research and development for technology adoption in the tourism sector

- enhancing digital services for businesses, and

- simplifying, updating and revising policies and regulations related to digitalisation in the tourism sector.

Implementing the action plans above could accelerate digital transformation in Indonesia’s tourism industry. In doing so, it would increase the quality of tourism services on offer for people interested in visiting Indonesia.

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Operations Manager

Senior Education Technologist

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

unsustainable

sustainability • ethics • climate • waste • renewables • ecology • poverty • equality

Negative Impacts of Tourism in Bali: A Comprehensive Guide

In this article, we explore the negative impacts of tourism in Bali, such as environmental issues and effects on equality, as well as touching on some of the positive consequences of tourism.

By Victoria Heinz, of www.guideyourtravel.com All images courtesy of Victoria Heinz

Have you ever dreamed of visiting the beautiful beaches and temples of Bali? This Balinese paradise is a popular tourist destination for many travellers, however it’s important to be aware that tourism may have its drawbacks.

In this article we will examine some of the negative impacts that travel in Bali can have on both the people and environment. From increased infrastructure problems to waste management issues – it pays to do your research before planning a trip, especially if you’re planning to visit popular areas like Uluwatu or Canggu. So read on to find out more about these potential pitfalls and how you can make conscious choices while enjoying Bali!

As any traveller to Indonesia is aware, the country is brimming with lush nature and unique wildlife. It’s a paradise for anyone looking to explore or escape in its natural beauty. However, beneath the surface lies an environmental crisis facing Indonesia today that demands action from both local and international travellers alike.

Table of Contents

Overview of Indonesia’s Current Environmental Situation

Indonesia is currently facing a significant environmental challenge. The rapid expansion of industries such as mining, agriculture, and forestry has resulted in deforestation, soil degradation, and air pollution. Additionally, the country’s coastline and marine life have been heavily impacted by plastic waste pollution.

The government has made some strides in addressing these issues by implementing policies and programs aimed at conserving the environment, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions and promoting sustainable agriculture . However, much more needs to be done to protect Indonesia’s vast natural resources for future generations .

The Most Pressing Environmental Issue in Indonesia – Deforestation and Land Conversion

Indonesia is facing a critical environmental issue that requires immediate attention – deforestation and land conversion. As one of the most biodiverse countries in the world, Indonesia’s forests are home to countless species of flora and fauna. However, rampant deforestation for agriculture, logging, and mining activities is causing irreversible damage to these precious ecosystems.

This not only affects the environment but also the livelihoods of local communities and indigenous peoples who rely on these forests for survival. The scale of deforestation in Indonesia is staggering, making it an urgent concern that must be addressed to ensure the sustainability of the country’s natural resources and the well-being of its people.

What are the Negative Impacts of Tourism in Bali?

- Overcrowding Issues

As our world becomes more connected and travel becomes easier, more people are flocking to popular tourist destinations. Unfortunately, this influx of visitors has led to a host of overcrowding issues.

Certain areas simply aren’t equipped to handle the sheer volume of people, leading to increased pollution, traffic congestion, and unsustainable practices. It’s heartbreaking to see natural wonders like the beaches in Uluwatu and national parks in northern Bali overrun with tourists, leaving trails of litter and damage in their wake.

The challenge now is finding ways to balance the economic benefits of tourism with the need to preserve these destinations for future generations to enjoy. Can we encourage sustainable tourism practices and limit the number of visitors to these sensitive areas? It’s a difficult question to answer, but it’s one that we must grapple with if we hope to protect these precious resources.

- Environmental Damage

As more and more people travel to exotic destinations, the impact on local ecosystems cannot be underestimated. While tourism can provide much-needed economic stimulus to an area, it can also lead to environmental damage if visitors are not conscientious.

Sun tanning on coral reefs can actually bleach and kill these delicate structures, while littering can overwhelm local sanitation systems and pollute waterways. This is especially a problem in southern Bali and neighbouring islands like Flores . It is important for tourists to understand the impact of their actions on the environment and to take steps to minimise their footprint while still enjoying all the beauty and wonder that our planet has to offer.

- Loss of Traditional Cultural Practices

Balinese culture has always been a source of pride and identity for its people. However, with the rise of tourism in recent years, the influx of foreign visitors has brought significant changes to traditional cultural practices.

While tourism has brought economic benefits to the Balinese people, it has also resulted in some traditional practices becoming lost or forgotten. Sadly, many younger Balinese generations do not have the same appreciation or understanding of their cultural heritage as their elders do.

It’s important for us to remember that preserving these customs and traditions is vital in maintaining the unique identity of the Balinese people. The loss of these practices can result in the homogenization of cultures worldwide, which would be a great shame.

- Increase in Prices

As the economy grows, so does the demand for goods and services. However, this surge in demand has also brought with it a rise in prices. Unfortunately, this means that many locals may find it increasingly difficult to afford necessities such as housing, food, and healthcare.

While it’s great to see our economy thriving, it’s important to ensure that no one is left behind. We must work together to find solutions that allow everyone in our community to access the goods and services they need to lead happy and healthy lives.

- Economic Inequality

Economic inequality has become a growing concern in many places around the world, especially in areas like Bali where wealthy tourists flock for their vacations. The trend of these travellers outbidding local residents for available housing and properties has been on the rise, leading to an ever-widening gap between the two groups.

This inequality can have devastating consequences, such as pushing out long-time residents and making it nearly impossible for them to find affordable housing. As a result, locals are left at a significant disadvantage compared to those who have more financial resources.

- Negative Impact on Local Economy

Tourism has undoubtedly provided financial benefits to Bali, but the extent of these gains is debatable. Unfortunately, much of the wealth generated is not finding its way into the hands of local businesses and individuals, which is concerning.

Instead, multinational companies appear to be reaping most of the rewards. This has created a negative impact on the local economy, as Bali is becoming increasingly reliant on outside businesses for revenue.

As a result, the Balinese are struggling to keep their businesses afloat, which can have significant consequences for the island’s overall economic stability. It is vital that Bali’s tourism industry takes a more balanced approach to ensure that both local businesses and multinational corporations benefit from the tourism boom.

What are Three Positive Consequences of Tourism in Bali?

The effects of tourism aren’t all bad and it’s important to recognise the positive impacts as well as the negative ones.

- Boosting Economic Growth

Bali has been experiencing a significant economic growth boost thanks to the surge in tourism. The influx of visitors has brought in tremendous revenue to the local economy, allowing the region to invest heavily in various infrastructure projects.

The island now boasts modern facilities, high-end accommodations, and top-notch dining options, attracting even more tourists to this vibrant location. With the expansion of new attractions, Bali’s economy shows no signs of slowing down, and the local market continues to thrive. There is no denying that tourism has become a crucial driver of economic growth in Bali, bringing with it endless opportunities for progress and development.

- Creating Job Opportunities

Not only does tourism in Bali provide people with a chance to explore new places and cultures, but it also generates job opportunities for locals. The impact of tourism is particularly profound in rural areas where employment options are scarce.

By providing direct jobs such as tour guides, hotel staff, and drivers, as well as indirectly creating jobs through the demand for local products and services, tourism plays a vital role in sustaining local economies.

- Spreading Cultural Awareness

As tourists flock to new destinations, they bring with them a desire to experience the local culture, to see and understand what makes a place unique. This desire to learn creates opportunities for locals to share their traditions, arts, and crafts with a broader audience, enabling a cultural exchange that benefits everyone involved.

Through tourism, visitors gain a deeper appreciation for the local way of life, while locals are able to showcase the best of their communities and preserve their cultural heritage. It’s a win-win scenario that enhances local culture while creating lasting connections between people from around the world.

About the Author

Victoria is a travel blogger and writer from Germany who now calls Bali her permanent home. She works full-time on her two travel blogs www.guideyourtravel.com and www.myaustraliatrip.com and her sites aim to provide helpful and realistic travel advice.

Share this article

Related articles:.

- Eco-Friendly Tourism in India: 10 Green Travel Destinations

- Sustainable Bali Tourism: How to be a Better Bali Tourist

- A Sustainable Guide to Edinburgh

- 9 Best Ways to Visit Costa Rica Sustainably: A 2024 Guide

- How to Travel Sustainably in New England: A Visitor's Guide

- Green Train Travel - Is Traveling by Train Finally Replacing The Plane?

hosted by greengeeks

CONTACT Authors Submissions

In the spirit of reconciliation Unsustainable Magazine acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of country throughout Australia and their connections to land, sea and community. We pay our respect to the Elders past and present and extend that respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples today.

© unsustainable 2024

International Handbook of Disaster Research pp 2413–2424 Cite as

Tourism Industry and the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study in Indonesia

- Huong Ha 2 &

- Timothy Wong 3

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 October 2023

46 Accesses

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020–2021 has devastated most economies. According to the latest forecast by International Monetary Fund ( 2020 ), a 5.4% contraction in global GDP in 2021 was projected. The global economy had been badly hit, as global trade declined and tourism was brought to a halt. With the shrink in the global economy and expected harsh conditions, Indonesia had reduced its 2020 GDP growth outlook to 2.3%, down from 5.3%. Indonesia is well-known among tourists for its iconic landscape and distinctive culture of both its big islands, such as Java and Sumatra, as well as small islands such as Komodo Island, Lombok, and Wakatobi Island. This main attraction had brought about significant growth in tourism in these islands over the years. However, with an escalating number of COVID-19 cases and related deaths being reported in Indonesia, the country’s immediate priority would inevitably be to mitigate the impact of the pandemic.

Thus, this chapter aims to shed light on the strategies adopted by the tourism industry in Indonesia as well as the experiences it has encountered during the COVID-19 pandemic and seeks to explore how the industry could recover from this difficult circumstance. The preliminary findings reveal that there is an increasing need for the government to improve the business environment by having proper policies and putting in place effective mechanisms for coordinating nationwide efforts to enable speedy recovery for a more resilient and sustainable tourism workforce.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Agarwal, R., Santoso, A., Tan, K. T., & Wibowo, P. (2021). Ten ideas to unlock Indonesia’s growth after COVID-19. McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/asia-pacific/ten-ideas-to-unlock-indonesias-growth-after-covid-19

Al Jazeera. (2021, February 5). COVID slammed Indonesia’s economy hard in 2020, data shows. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2021/2/5/covid-slammed-indonesias-economy-hard-in-2020-data-show

Borsuk, R. (2021, February 11). Indonesia’s joblessness: Worsened by the pandemic . NTU RSIS. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/CO21026.pdf

Budeanu, A. (2005). Impacts and responsibilities for sustainable tourism: A tour operator’s perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 13 , 89–97.

Article Google Scholar

Djalante, R., Lassa, J., Setiamarga, D., Sudjatma, A., Indrawan, M., Haryanto, B., Mahfud, C., Sinapoy, M. S., Djalante, S., Rafliana, I., Gunawan, L. A., Surtiari, G., & Warsilah, H. (2020). Review and analysis of current responses to COVID-19 in Indonesia: Period of January to March 2020. Progress in Disaster Science, 6 , 100091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100091

Hakim, L. (2020). COVID-19, tourism, and small islands in Indonesia: Protecting fragile communities in the global coronavirus pandemic. Cultures Journal of Marine and Island, 9 . https://doi.org/10.21463/jmic.2020.09.1.08

Hewson, J. (2018, March 21). Tourism plan threatens Indonesia’s environment . TRT World. https://www.trtworld.com/life/tourism-plan-threatens-indonesia-s-environment-16079

Ikhwan, H., & Yulianto, V. I. (2020, June 17). How religions and religious leaders can help to combat the COVID-19 pandemic: Indonesia’s experience . The Conversation Media Group Ltd. https://theconversation.com/how-religions-and-religious-leaders-can-help-to-combat-the-covid-19-pandemic-indonesias-experience-140342

International Monetary Fund. (2020). World economic outlook reports . IMF. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO

KPMG. (2020a, October 16). Common challenges for business and government . KPMG. https://home.kpmg/xx/en/blogs/home/posts/2020/10/common-challenges-for-business-and-government-in-the-new-reality.html

KPMG. (2020b, March). Our new reality . KPMG. https://home.kpmg/my/en/home/insights/2020/03/the-business-implications-of-coronavirus.html

Manggi, T. H., & Wisnu, W. (2020, December 15). COVID-19’s impact on Indonesia’s economy and financial markets . Yusof Ishak Institute. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/ISEAS_Perspective_2020_142.pdf

Mulyanto, R. (2020, July 17). How Indonesia’s tourism industry is adapting to the pandemic. South China Morning Post . https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/travel-leisure/article/3093252/how-indonesias-tourism-industry-adapting-pandemic

Nugroho, Y., & Syarief, S. S. (2021). Grave failures in policy and communication in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspective, 2021 (113), 1–13.

Google Scholar

OECD. (2020). Tourism Policy Responses to the coronavirus (COVID-19) . OECD. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=124_124984-7uf8nm95se&title=Covid-19_Tourism_Policy_Responses

Parama, M. (2020). Worst period ever: Indonesia’s foreign tourist arrivals fall to lowest level since 2009. The Jakarta Post . https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/05/05/worst-period-ever-indonesias-foreign-tourist-arrivals-fall-to-lowest-level-since-2009.html

Rahman, D. F. (2020, December 2). Foreign tourist arrivals, hotel occupancy rate yet to recover in October: BPS. The Jakarta Post. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/12/02/oreign-tourist-arrivals-hotel-occupancy-rate-yet-to-recover-in-october-bps.html

Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research, 117 , 312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.015

Soshkin, M. (2019). If you build it, they will come: Why infrastructure is crucial to tourism growth and competitiveness . World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/09/why-infrastructure-is-crucial-to-tourism-growth-and-competitiveness/

Statista. (2021, March 31). Indonesia: Unemployment rate from 1999 to 2020 . Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/320129/unemployment-rate-in-indonesia/

Statista Research Department. (2022). Number of employees in tourism industry Indonesia 2011–2020 . Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1006336/total-number-of-employees-in-tourism-industry-indonesia/

Susan, O., John, G., & Rus’an, N. (2020). Indonesia in the time of Covid-19. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 56 (2), 143–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2020.1798581

Tay, T. F. (2020, 19 Aug). Singaporeans to get $320 million in tourism vouchers to boost sector. The Straits Times . https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/singaporeans-to-get-320-million-in-tourism-vouchers-to-boost-sector-says-heng-swee-keat

TheWorldCounts. (2021). Number of tourist arrivals . TheWorldCounts. https://www.theworldcounts.com/challenges/consumption/transport-and-tourism/negative-environmental-impacts-of-tourism/story

UNEP. (2019). Paradise lost? Travel and tourism industry takes aim at plastic pollution but more action needed . UNEP. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/paradise-lost-travel-and-tourism-industry-takes-aim-plastic-pollution-more

Vivek, L., Tracy, L., Khoon Tee, T., & Phillia, W. (2020, September 8). With effort, Indonesia can emerge from the COVID-19 crisis stronger . McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/asia-pacific/with-effort-indonesia-can-emerge-from-the-covid-19-crisis-stronger#

World Bank. (2021). Ensuring a more inclusive future for Indonesia through digital technologies . World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/07/28/ensuring-a-more-inclusive-future-for-indonesia-through-digital-technologies

Yulisman, L. (2020, July 11). Jakarta steps up battle against plastic waste with ban on single-use plastic bags. The Straits Times . https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/jakarta-steps-up-battle-against-plastic-waste-with-ban-on-single-use-plastic-bags

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Business and Centre of Excellence for Behavioural Insights at Work, Singapore University of Social Sciences, Singapore, Singapore

Singapore University of Social Sciences, Clementi, Singapore

Timothy Wong

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

NDRG (Asia Pacific Disaster Research Group), New Delhi, India

Amita Singh

Section Editor information

Singapore University of Social Sciences, Metropolis of Singapore, Singapore

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information