It’s normal for your mind to wander. Here’s how to maximise the benefits

Psychology researcher, Bond University

Associate Professor in Psychology, Bond University

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Bond University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Have you ever found yourself thinking about loved ones during a boring meeting? Or going over the plot of a movie you recently watched during a drive to the supermarket?

This is the cognitive phenomenon known as “ mind wandering ”. Research suggests it can account for up to 50% of our waking cognition (our mental processes when awake) in both western and non-western societies .

So what can help make this time productive and beneficial?

Mind wandering is not daydreaming

Mind wandering is often used interchangeably with daydreaming. They are both considered types of inattention but are not the same thing.

Mind wandering is related to a primary task, such as reading a book, listening to a lecture, or attending a meeting. The mind withdraws from that task and focuses on internally generated, unrelated thoughts.

On the other hand, daydreaming does not involve a primary, active task. For example, daydreaming would be thinking about an ex-partner while travelling on a bus and gazing out the window. Or lying in bed and thinking about what it might be like to go on a holiday overseas.

If you were driving the bus or making the bed and your thoughts diverted from the primary task, this would be classed as mind wandering.

The benefits of mind wandering

Mind wandering is believed to play an important role in generating new ideas , conclusions or insights (also known as “aha! moments”). This is because it can give your mind a break and free it up to think more creatively.

This type of creativity does not always have to be related to creative pursuits (such as writing a song or making an artwork). It could include a new way to approach a university or school assignment or a project at work. Another benefit of mind wandering is relief from boredom, providing the opportunity to mentally retreat from a monotonous task.

For example, someone who does not enjoy washing dishes could think about their upcoming weekend plans while doing the chore. In this instance, mind wandering assists in “passing the time” during an uninteresting task.

Mind wandering also tends to be future-oriented. This can provide an opportunity to reflect upon and plan future goals, big or small. For example, what steps do I need to take to get a job after graduation? Or, what am I going to make for dinner tomorrow?

Read more: Alpha, beta, theta: what are brain states and brain waves? And can we control them?

What are the risks?

Mind wandering is not always beneficial, however. It can mean you miss out on crucial information. For example, there could be disruptions in learning if a student engages in mind wandering during a lesson that covers exam details. Or an important building block for learning.

Some tasks also require a lot of concentration in order to be safe. If you’re thinking about a recent argument with a partner while driving, you run the risk of having an accident.

That being said, it can be more difficult for some people to control their mind wandering. For example, mind wandering is more prevalent in people with ADHD.

Read more: How your brain decides what to think

What can you do to maximise the benefits?

There are several things you can do to maximise the benefits of mind wandering.

- be aware : awareness of mind wandering allows you to take note of and make use of any productive thoughts. Alternatively, if it is not a good time to mind wander it can help bring your attention back to the task at hand

context matters : try to keep mind wandering to non-demanding tasks rather than demanding tasks. Otherwise, mind wandering could be unproductive or unsafe. For example, try think about that big presentation during a car wash rather than when driving to and from the car wash

content matters : if possible, try to keep the content positive. Research has found , keeping your thoughts more positive, specific and concrete (and less about “you”), is associated with better wellbeing. For example, thinking about tasks to meet upcoming work deadlines could be more productive than ruminating about how you felt stressed or failed to meet past deadlines.

- Consciousness

- Daydreaming

- Concentration

- Mind wandering

Director of STEM

Community member - Training Delivery and Development Committee (Volunteer part-time)

Chief Executive Officer

Finance Business Partner

Head of Evidence to Action

mikroman6/Moment/Getty Images

“Mind-wandering can be a benefit and a curse”

Scientists finally know why we get distracted — and how we can stay on track

More than just a distraction, mind-wandering (and its cousin, daydreaming) may help us prepare for the future

When psychologist Jonathan Smallwood set out to study mind-wandering about 25 years ago, few of his peers thought that was a very good idea. How could one hope to investigate these spontaneous and unpredictable thoughts that crop up when people stop paying attention to their surroundings and the task at hand? Thoughts that couldn’t be linked to any measurable outward behavior?

But Smallwood, now at Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada, forged ahead. He used as his tool a downright tedious computer task that was intended to reproduce the kinds of lapses of attention that cause us to pour milk into someone’s cup when they asked for black coffee. And he started out by asking study participants a few basic questions to gain insight into when and why minds tend to wander, and what subjects they tend to wander toward. After a while, he began to scan participants’ brains as well, to catch a glimpse of what was going on in there during mind-wandering.

Smallwood learned that unhappy minds tend to wander in the past, while happy minds often ponder the future . He also became convinced that wandering among our memories is crucial to help prepare us for what is yet to come. Though some kinds of mind-wandering — such as dwelling on problems that can’t be fixed — may be associated with depression , Smallwood now believes mind-wandering is rarely a waste of time. It is merely our brain trying to get a bit of work done when it is under the impression that there isn’t much else going on.

Smallwood, who coauthored an influential 2015 overview of mind-wandering research in the Annual Review of Psychology, is the first to admit that many questions remain to be answered.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

There are good reasons for your mind to wander.

Is mind-wandering the same thing as daydreaming, or would you say those are different?

I think it’s a similar process used in a different context. When you’re on holiday, and you’ve got lots of free time, you might say you’re daydreaming about what you’d like to do next. But when you’re under pressure to perform, you’d experience the same thoughts as mind-wandering.

I think it is more helpful to talk about the underlying processes: spontaneous thought, or the decoupling of attention from perception, which is what happens when our thoughts separate from our perception of the environment. Both these processes take place during mind-wandering and daydreaming.

It often takes us a while to catch ourselves mind-wandering. How can you catch it to study it in other people?

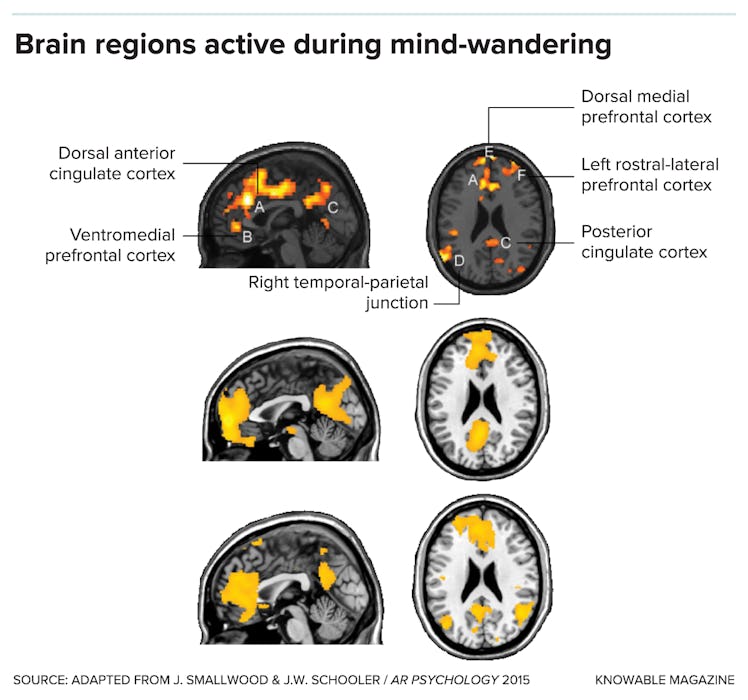

In the beginning, we gave people experimental tasks that were really boring, so that mind-wandering would happen a lot. We would just ask from time to time, “Are you mind-wandering?” while recording the brain’s activity in an fMRI scanner.

But what I’ve realized, after doing studies like that for a long time, is that if we want to know how thinking works in the real world, where people are doing things like watching TV or going for a run, most of the data we have are never going to tell us very much.

So we are now trying to study these situations . And instead of doing experiments where we just ask, “Are you mind-wandering?” we are now asking people a lot of different questions, like: “Are your thoughts detailed? Are they positive? Are they distracting you?”

How and why did you decide to study mind-wandering?

I started studying mind-wandering at the start of my career when I was young and naive.

I didn’t really understand at the time why nobody was studying it. Psychology was focused on measurable, outward behavior then. I thought to myself: That’s not what I want to understand about my thoughts. What I want to know is: Why do they come, where do they come from, and why do they persist even if they interfere with attention to the here and now?

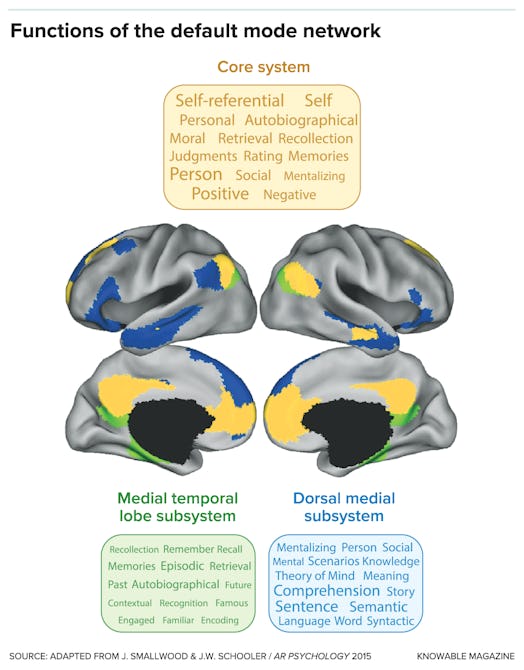

Around the same time, brain imaging techniques were developing, and they were telling neuroscientists that something happens in the brain even when it isn’t occupied with a behavioral task. Large regions of the brain, now called the default mode network , did the opposite: If you gave people a task, the activity in these areas went down.

When scientists made this link between brain activity and mind-wandering, it became fashionable. I’ve been very lucky, because I hadn’t anticipated any of that when I started my Ph.D., at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow. But I’ve seen it all pan out.

Different subsystems are responsible for different areas of cognition.

Would you say, then, that mind-wandering is the default mode for our brains?

It turns out to be more complicated than that. Initially, researchers were very sure that the default mode network rarely increased its activity during tasks. But these tasks were all externally focused — they involved doing something in the outside world. When researchers later asked people to do a task that doesn’t require them to interact with their environment — like think about the future — that activated the default mode network as well.

More recently, we have identified much simpler tasks that also activate the default mode network. If you let people watch a series of shapes like triangles or squares on a screen, and every so often you surprise them and ask something — like, “In the last trial, which side was the triangle on?”— regions within the default mode network increase activity when they’re making that decision . That’s a challenging observation if you think the default mode network is just a mind-wandering system.

But what both situations have in common is the person is using information from memory. I now think the default mode network is necessary for any thinking based on information from memory — and that includes mind-wandering.

Would it be possible to demonstrate that this is indeed the case?

In a recent study, instead of asking people whether they were paying attention, we went one step further . People were in a scanner reading short factual sentences on a screen. Occasionally, we’d show them a prompt that said, “Remember,” followed by an item from a list of things from their past that they’d provided earlier. So then, instead of reading, they’d remember the thing we showed them. We could cause them to remember.

What we find is that the brain scans in this experiment look remarkably similar to mind-wandering. That is important: It gives us more control over the pattern of thinking than when it occurs spontaneously, like in naturally occurring mind-wandering. Of course, that is a weakness as well, because it’s not spontaneous. But we’ve already done lots of spontaneous studies.

When we make people remember things from the list, we recapitulate quite a lot of what we saw in spontaneous mind-wandering. This suggests that at least some of the activity we see when minds wander is indeed associated with the retrieval of memories. We now think the decoupling between attention and perception happens because people are remembering.

The science of mind wandering is visible in brain scans.

Nowadays, it seems that many of the idle moments in which our minds would previously have wandered are now spent scrolling our phones. How do you think that might change how our brain functions?

The interesting thing about social media and mind-wandering, I think, is that they may have similar motivations. Mind-wandering is very social. In our studies , we’re locking people in small booths and making them do these tasks and they keep coming out and saying, “I’m thinking about my friends.” That’s telling us that keeping up with others is very important to people.

Social groups are so important to us as a species that we spend most of our time trying to anticipate what others are going to do, and I think social media is filling part of the gap that mind-wandering is trying to fill. It’s like mainlining social information: You can try to imagine what your friend is doing, or you can just find out online. Though, of course, there is an important difference: When you’re mind-wandering, you’re ordering your own thoughts. Scrolling social media is more passive.

Could there be a way for us to suppress mind-wandering in situations where it might be dangerous?

Mind-wandering can be a benefit and a curse, but I wouldn’t be confident that we know yet when it would be a good idea to stop it. In our studies at the moment, we are trying to map how people think across a range of different types of tasks. We hope this approach will help us identify when mind-wandering is likely to be useful or not — and when we should try to control it and when we shouldn’t.

For example, in our studies, people who are more intelligent don’t mind wandering so often when the task is hard but can do it more when tasks are easy . It is possible that they are using idle time when the external world is not demanding their attention to think about other important matters. This highlights the uncertainty about whether mind wandering is always a bad thing because this sort of result implies it is likely to be useful under some circumstances.

This map — of how people think in different situations — has become very important in our research. This is the work I’m going to focus on now, probably for the rest of my career.

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine , an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews. Sign up for the newsletter .

This article was originally published on Sep. 10, 2022

- Mental Health

The power of daydreams: 4 studies on the surprising science of mind-wandering

[ted id=1607 width=560 height=315]

What makes us happy? It’s one of the most complicated puzzles of human existence — and one that, so far, 87 speakers have explored in TEDTalks .

In today’s talk , Matt Killingsworth (who studied under Dan Gilbert at Harvard) shares a novel approach to the study of happiness — an app, Track Your Happiness , which allows people to chart their feelings on a moment-by-moment basis. As they go about their day, app users get random pings, asking them to share their current activity and note their mood. When Killingsworth gave this talk at TEDxCambridge in 2011, the app had collected data from more than 15,000 people in 80 countries, representing a wide range of ages, education levels and occupations. In this talk, Killingsworth reveals a very surprising finding: that mind-wandering appears to factor heavily into this happiness equation.

“As human beings, we have this unique ability to have our minds stray,” says Killingsworth on the TEDx stage . “This ability to focus our attention on something other than the present is amazing — it allows us to learn and plan and reason.”

While most people think of mind-wandering as a lifting escape from daily drudgery, the Track Your Happiness data shows that this may not the case. In fact, mind-wandering appears to be correlated with unhappiness . When people were mind-wandering, they reported feeling happy only 56% of the time. Meanwhile, when they were focused on the present moment, they reported feeling happy 66% of the time. This effect was true regardless of the activity the person was doing — be it waiting in a traffic jam or eating a delicious dinner. (Read Killingsworth’s study, published in the journal Science in 2010 , to see a breakdown of mind-wandering rates by activity.)

According to Killingsworth’s data, people mind-wander most when in the shower and least when they are having sex. But, still, mind-wandering is a constant. Overall, people mind-wander 47% of the time. Perhaps not such a good thing if it relates to unhappiness,

To hear more about mind-wandering — and about the importance of studying happiness in general — watch Killingsworth’s talk . And after the jump, read several more fascinating studies on the psychology of mind-wandering — some of which will make you feel better about your daydreaming.

A relationship to working memory Mind-wandering might make us feel less content, but it could also have a functional purpose. A recent study published in the journal Psychological Science suggests that mind-wandering might be a sign of a high capacity working memory — in other words, the ability to think about multiple things at once. Researchers asked study participants to press a button and, as they went, checked in to see if their minds were wandering. After the task was complete, researchers gave participants a measure of their working memory. Interestingly, those who were found to be frequent mind-wanderers during the first task showed a greater capacity of working memory. Researcher Jonathan Smallwood of the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Science explains, “Our results suggest that the sorts of planning that people do quite often in daily life — when they’re on the bus, when they’re cycling to work, when they’re in the shower — are probably supported by working memory. Their brains are trying to allocate resources to the most pressing problems.”

A key to memory formation Mind-wandering might also play a vital function in helping us form memories. New York University neuroscientist Arielle Tambini looked at memory consolidation in this study published in the journal Neuron in 2010 . Participants in the study were asked to look at pairs of images and, in between, were instructed to take a break to think about anything they wanted. Using fMRI, the researchers looked at the activity in the hippocampus cortical regions while they did both. The study showed that these two areas of the brain appear to work together — and that the greater the levels of brain activity in both areas, the stronger the subjects’ recall of the image pairing was. Explains Lila Davichi, who oversaw the study , “Your brain is working for you when you’re resting, so rest is important for memory and cognitive function. This is something we don’t appreciate much, especially when today’s information technologies keep us working round-the-clock … Taking a coffee break after class can actually help you retain that information you just learned.”

A creative boost As the cliché goes, the best ideas usually come when you are least expecting them. A recent study published in the journal Psychological Science gives a clue as to why. A research team led by Benjamin Baird and Jonathan Schooler of the University of California at Santa Barbara asked participants to take “unusual uses” tests — brainstorming alternate ways to use an everyday object like a toothpick for two minutes. Study participants did two of these sessions, and then were given a 12-minute break, during which they were asked to rest, perform a demanding memory exercise or do a reaction time activity designed to maximize their mind-wandering. After the break, they did four more unusual uses tests — two of them repeats. While all of the groups performed comparably on the two new unusual uses lists, the group that had performed the mind-wandering tasks performed 41% better then the other groups on the unusual uses lists they were repeating. “The implication is that mind-wandering was only helpful for problems that were already being mentally chewed on. It didn’t seem to lead to a general increase in creative problem-solving ability,” says Baird .

- Subscribe to TED Blog by email

Comments (69)

Pingback: Tracking Mind-Wandering – Resonance

Pingback: 4 studies on the surprising science of mind-wandering | TED Blog | Miquel Blanch

Pingback: 4 Tips For Better Daydreaming / R.S. Mollison-Read

Pingback: TED Talks Pinned: Speaking of HapPINness | The English Learners' Blog

Pingback: momentary happiness please… Ted Talk | Hunt FOR Truth on wordpress

Pingback: On the science of Mind-wandering | Learning Sciences of Change

Pingback: Poetics Serendipity | Margo Roby: Wordgathering

Pingback: Matt Killingsworthy:想要快樂嗎?專注於當下吧! | TEDxTaipei

Pingback: Issue 27 – Happy Thanksgiving! — TLN

Pingback: Abundance. | Cindy Mantai Writing & Editing

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

How to Let Your Mind Wander

Research suggests that people with freely moving thoughts are happier. Easy, repetitive activities like walking can help get you in the right mindset.

By Malia Wollan

“Sometimes you just want to let your mind go free,” says Julia Kam, a cognitive neuroscientist who directs the Internal Attention Lab at the University of Calgary. Kam became interested in her subject 15 years ago as an undergraduate struggling with her own distracted thoughts during lectures. “I came into the field wanting to find a cure,” she says. But the deeper she got into research, the more she came to appreciate the freedom of an unfocused mind. “When your thoughts are just jumping from one topic to the next without an overarching theme or goal, that can be very liberating,” she says.

Researchers have found that people spend up to 50 percent of their time mind-wandering. Some internal thinking can be detrimental, especially the churning, ruminative sort often associated with depression and anxiety. Try instead to cultivate what psychologists call freely moving thoughts. Such nimble thinking might start with a yearning to see your grandmother, then careen to that feeling you get when looking down at clouds from an airplane, and then suddenly you’re pondering how deep you’d have to bore into the earth below your feet before you hit magma. Research suggests that people who do more of that type of mind-wandering are happier.

Facilitate unconstrained thinking by engaging in an easy, repetitive activity like walking; avoid it during riskier undertakings like driving. You’ll find it harder to go free-ranging if you’re myopically worried about something in your personal life, like an illness or an argument with a spouse.

For a recent study, Kam hooked subjects up for an electroencephalogram and then had them do a mundane task on a keyboard while periodically asking them about their thoughts. She was able to see, for the first time, a distinct neural marker for freely moving thoughts, which caused an increase in alpha waves in the brain’s frontal cortex. This is the same region where scientists see alpha waves in people doing creative problem-solving. We live in a culture that values work and productivity over almost everything else, but remember, your mind is yours. Make space to think in idle ways unrelated to tasks. “It can replenish you,” Kam says.

Explore The New York Times Magazine

The Interview: The actress Jenna Ortega talked about learning to protect herself and the hard lessons of childhood stardom .

Audre Lorde’s Afterlives: A new biography shows how the feminist thinker, who is celebrated as a prophet of empowerment and self-care , saw our future.

The Meaning of ‘Genocide’: Debates over how to describe conflicts in Gaza, Myanmar and elsewhere are channeling a controversy as old as the word itself .

Biden’s Interrupted Presidency: Joe Biden sought the presidency nearly all his life. When he finally got there, it brought out his best — and eventually his worst .

A Medical Mystery in Canada: Doctors identified a cluster of patients with similar, unexplained brain diseases. In the absence of answers, a political maelstrom ensued .

A Wandering Mind Isn't Just A Distraction. It May Be Your Brain's Default State.

Senior Writer, The Huffington Post

Even if you don’t consider yourself a daydreamer, you probably spend a lot of time in a state of mental wandering ― it’s natural for your mind to drift away from the present moment when you’re in the shower, walking to work or doing the dishes.

In recent years, scientists have been paying a lot more attention to mind-wandering, an activity that takes up as much as 50 percent of our waking hours . Psychologists previously tended to view mind-wandering as largely useless, but an emerging body of research suggests that it is a natural and healthy part of our mental lives.

Researchers from the University of British Columbia and the University of California, Berkeley conducted a review of over 200 studies to highlight the relationship between mind-wandering ― often defined in psychological literature as “task-unrelated thought,” or TUT ― and the thinking processes involved in creativity and some mental illnesses, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety and depression.

“Sometimes the mind moves freely from one idea to another, but at other times it keeps coming back to the same idea, drawn by some worry or emotion,” Dr. Kalina Christoff, lead study author and principal investigator of the Cognitive Neuroscience of Thought Laboratory at UBC, said in a statement.

“Understanding what makes thought free and what makes it constrained is crucial because it can help us understand how thoughts move in the minds of those diagnosed with mental illness,” she said.

The Role Of A Wandering Mind

Traditionally, mind-wandering has been defined as thinking that arises spontaneously, without relating to any sort of task or external input. But this definition is only a starting point: Without external focus, the researchers explain, the mind moves from one thought to another ― jumping between memories, imaginings, plans and goals.

This default “spontaneous mode” can be hemmed in in two ways: A person can deliberately turn their attention to a task, or, in the case of someone with a mental health issue, focus can happen because thoughts have gotten stuck on a persistent worry or pulled away by an environmental distraction.

On a neurological level, the brain’s default mode network ― a broad network that engages many different cognitive processes and regions on the internal surface of the brain ― activates when our minds wander. In contrast, when we focus our attention on a goal, plan or environmental stimulus, the part of the brain devoted to external attention is more active.

Specifically, the researchers pinpointed the memory and imaginative centers within the default mode network as being largely responsible for the variety of our spontaneous thoughts.

“You’re jumping around from one thing to another,” Zachary Irving, a postdoctoral scholar at the University of California, Berkeley and study co-author who has ADHD, told The Huffington Post. “We think that’s the default state of these memory and imaginative structures.”

A Creative Mind Is A Wandering Mind

Creative thinking can be an extension of ordinary mind-wandering, the researchers explained, and a growing body of research has linked daydreaming with creativity . In highly creative people, psychologists have observed a tendency toward a variation on mind-wandering known as “ positive-constructive daydreaming ,” in which has also been associated with self-awareness, goal-oriented thinking and increased compassion.

The free play of thoughts that occurs in mind-wandering may enable us to think more flexibly and draw more liberally upon our vast internal reservoir of memories, feelings and images in order to create new and unusual connections.

“Mind-wandering in the sense of the mind moving freely from one idea to another has huge benefits in terms of arriving at new ideas,” Christoff said. “It’s by virtue of free movement that we generate new ideas, and that’s where creativity lies.”

What Mind-Wandering Can Tell Us About Mental Illness

This type of mental activity can provide an important window into the thinking patterns that underly psychological disorders involving alterations in spontaneous thought.

The mind of someone with ADHD, for example, wanders more widely and frequently than that of an average individual. In someone with anxiety and depression, the mind has an unusually strong tendency to get stuck on a particular worry or negative thought.

“Disorders like ADHD and anxiety and depression aren’t totally disconnected from what normally goes on in the mind,” Irving said. “There’s this ordinary ebb and flow of thoughts, where you’re moving from mind-wandering to sticky thoughts to goal-directed thoughts. ... We think of these disorders as exaggerated versions of those sorts of ordinary thoughts.”

So despite what your elementary school teachers may have told you, it’s perfectly fine to let your thoughts wander every once in a while. But if you find your mind wandering too much or getting stuck on negative thoughts, it may be time to seek help.

From Our Partner

Huffpost shopping’s best finds, more in life.

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Does Mind-Wandering Make You Unhappy?

What are the major causes of human happiness?

It’s an important question but one that science has yet to fully answer. We’ve learned a lot about the demographics of happiness and how it’s affected by conditions like income, education, gender, and marriage. But the scientific results are surprising: Factors like these don’t seem to have particularly strong effects. Yes, people are generally happier if they make more money rather than less, or are married instead of single, but the differences are quite modest.

Although our goals in life often revolve around these sorts of milestones, my research is driven by the idea that happiness may have more to do with the contents of our moment-to-moment experiences than with the major conditions of our lives. It certainly seems that fleeting aspects of our everyday lives—such as what we’re doing, who we’re with, and what we’re thinking about—have a big influence on our happiness, and yet these are the very factors that have been most difficult for scientists to study.

A few years ago, I came up with a way to study people’s moment-to-moment happiness in daily life on a massive scale, all over the world, something we’d never been able to do before. This took the form of trackyourhappiness.org, which uses iPhones to monitor people’s happiness in real time.

My results suggest that happiness is indeed highly sensitive to the contents of our moment-to-moment experience. And one of the most powerful predictors of happiness is something we often do without even realizing it: mind-wandering.

Be here now

As human beings, we possess a unique and powerful cognitive ability to focus our attention on something other than what is happening in the here and now. A person could be sitting in his office working on his computer, and yet he could be thinking about something else entirely: the vacation he had last month, which sandwich he’s going to buy for lunch, or worrying that he’s going bald.

This ability to focus our attention on something other than the present is really amazing. It allows us to learn and plan and reason in ways that no other species of animal can. And yet it’s not clear what the relationship is between our use of this ability and our happiness.

You’ve probably heard people suggest that you should stay focused on the present. “Be here now,” as Ram Dass advised back in 1971. Maybe, to be happy, we need to stay completely immersed and focused on our experience in the moment. Maybe this is good advice; maybe mind-wandering is a bad thing.

On the other hand, when our minds wander, they’re unconstrained. We can’t change the physical reality in front of us, but we can go anywhere in our minds. Since we know people want to be happy, maybe when our minds wander we tend to go to someplace happier than the reality that we leave behind. It would make a lot of sense. In other words, maybe the pleasures of the mind allow us to increase our happiness by mind-wandering.

Since I’m a scientist, I wanted to try to resolve this debate with some data. I collected this data using trackyourhappiness.org.

How does it work? Basically, I send people signals at random times throughout the day, and then I ask them questions about their experience at the instant just before the signal. The idea is that if we can watch how people’s happiness goes up and down over the course of the day, and try to understand how things like what people are doing, who they’re with, what they’re thinking about, and all the other factors that describe our experiences relate to those ups and downs in happiness, we might eventually be able to discover some of the major causes of human happiness.

This essay is based a 2011 TED talk by Matt Killingsworth.

In the results I’m going to describe, I will focus on people’s responses to three questions. The first was a happiness question: How do you feel? on a scale ranging from very bad to very good. Second, an activity question: What are you doing? on a list of 22 different activities including things like eating and working and watching TV. And finally a mind-wandering question: Are you thinking about something other than what you’re currently doing? People could say no (in other words, they are focused only on their current activity) or yes (they are thinking about something else). We also asked if the topic of those thoughts is pleasant, neutral, or unpleasant. Any of those yes responses are what we called mind-wandering.

We’ve been fortunate with this project to collect a lot of data, a lot more data of this kind than has ever been collected before, over 650,000 real-time reports from over 15,000 people. And it’s not just a lot of people, it’s a really diverse group, people from a wide range of ages, from 18 to late 80s, a wide range of incomes, education levels, marital statuses, and so on. They collectively represent every one of 86 occupational categories and hail from over 80 countries.

Wandering toward unhappiness

So what did we find?

First of all, people’s minds wander a lot. Forty-seven percent of the time, people are thinking about something other than what they’re currently doing. Consider that statistic next time you’re sitting in a meeting or driving down the street.

How does that rate depend on what people are doing? When we looked across 22 activities, we found a range—from a high of 65 percent when people are taking a shower or brushing their teeth, to 50 percent when they’re working, to 40 percent when they’re exercising. This went all the way down to sex, when 10 percent of the time people’s minds are wandering. In every activity other than sex, however, people were mind-wandering at least 30 percent of the time, which I think suggests that mind-wandering isn’t just frequent, it’s ubiquitous. It pervades everything that we do.

How does mind-wandering relate to happiness? We found that people are substantially less happy when their minds are wandering than when they’re not, which is unfortunate considering we do it so often. Moreover, the size of this effect is large—how often a person’s mind wanders, and what they think about when it does, is far more predictive of happiness than how much money they make, for example.

Now you might look at this result and say, “Ok, on average people are less happy when they’re mind-wandering, but surely when their minds are straying away from something that wasn’t very enjoyable to begin with, at least then mind-wandering will be beneficial for happiness.”

As it turns out, people are less happy when they’re mind-wandering no matter what they’re doing. For example, people don’t really like commuting to work very much; it’s one of their least enjoyable activities. Yet people are substantially happier when they’re focused only on their commute than when their mind is wandering off to something else. This pattern holds for every single activity we measured, including the least enjoyable. It’s amazing.

But does mind-wandering actually cause unhappiness, or is it the other way around? It could be the case that when people are unhappy, their minds wander. Maybe that’s what’s driving these results.

We’re lucky in this data in that we have many responses from each person, and so we can look and see, does mind-wandering tend to precede unhappiness, or does unhappiness tend to precede mind-wandering? This gives us some insight into the causal direction.

As it turns out, there is a strong relationship between mind-wandering now and being unhappy a short time later, consistent with the idea that mind-wandering is causing people to be unhappy. In contrast, there’s no relationship between being unhappy now and mind-wandering a short time later. Mind-wandering precedes unhappiness but unhappiness does not precede mind-wandering. In other words, mind-wandering seems likely to be a cause, and not merely a consequence, of unhappiness.

How could this be happening? I think a big part of the reason is that when our minds wander, we often think about unpleasant things: our worries, our anxieties, our regrets. These negative thoughts turn out to have a gigantic relationship to (un)happiness. Yet even when people are thinking about something they describe as neutral, they’re still considerably less happy than when they’re not mind-wandering. In fact, even when they’re thinking about something they describe as pleasant, they’re still slightly less happy than when they aren’t mind-wandering at all.

The lesson here isn’t that we should stop mind-wandering entirely—after all, our capacity to revisit the past and imagine the future is immensely useful, and some degree of mind-wandering is probably unavoidable. But these results do suggest that mind-wandering less often could substantially improve the quality of our lives. If we learn to fully engage in the present , we may be able to cope more effectively with the bad moments and draw even more enjoyment from the good ones.

About the Author

Matt Killingsworth

Matt Killingsworth, Ph.D., is a Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholar. He studies the nature and causes of human happiness, and is the creator of www.trackyourhappiness.org which uses smartphones to study happiness in real-time during everyday life. Recent research topics have included the relationship between happiness and the content of everyday experiences, the percentage of everyday experiences that are intrinsically valuable, and the degree of congruence between the causes of momentary happiness and of one's overall satisfaction with life. Matt earned his Ph.D. in psychology at Harvard University.

You May Also Enjoy

Here’s How Mindful You Are

What is Mindfulness?

The psychology of stress.

Mindful Kids, Peaceful Schools

Toward a More Mindful Nation

The Science of Mindfulness

clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

Here’s why you should let your mind wander — and how to set it free

If you’re overwhelmed, you’re not alone. Even before the pandemic, 60 percent of adults in the United States reported sometimes feeling too busy to enjoy life, according to a report from the Pew Research Center, and 52 percent said they were usually trying to do at least two things at once.

Some experts say the antidote is free and accessible to anyone willing to try it: setting aside some time to let your mind wander.

This practice has been portrayed recently as “doing nothing,” thanks in part to Olga Mecking’s 2020 book, “ Niksen: Embracing the Dutch Art of Doing Nothing .” But if the idea of trying to squeeze time to do nothing into an already packed schedule sounds more stressful than soothing, fear not. According to Erik Dane , an associate professor of organizational behavior in the Olin Business School at Washington University in St. Louis, doing nothing doesn’t necessarily mean simply staring out the window (although it can).

“From a biological and a psychological standpoint, we’re almost never doing nothing,” Dane said. He and other experts believe that simply slowing down enough to give your mind a chance to wander and reflect can be all the “nothingness” you need to feel less harried.

Mind-wandering refers to thoughts that pop up spontaneously that aren’t connected to the task at hand or our surroundings, Dane said. “For example, memories bubble up, or we find ourselves anticipating any number of future states of affairs.” Given our busy lives, however, we often have to create an environment conducive to setting our minds free.

How this is done can vary from person to person, and even from day to day. Elisabeth Netherton , a psychiatrist and regional medical director with Houston-based Mindpath Health, said the main steps are to avoid responding to distractions or focusing on any specific task. “The whole goal is to shift into more of a reflective space,” she said. “It’s not even so much driven by what you’re actually doing but by the head space you’re in.”

One of the most attractive aspects of mind-wandering is its simplicity — something that many of us are craving as coronavirus restrictions continue to loosen and life resumes a more normal pace. If the self-care practices that fit your lifestyle during the earlier periods of the pandemic no longer make sense as your calendar fills up, creating a practice of allowing your mind to wander and reflect is an excellent low-key way to “refresh your toolbox,” Netherton said.

Benefits of letting your mind wander

According to Moshe Bar, a professor of neuroscience at Bar-Ilan University in Tel Aviv and the author of “ Mindwandering: How Your Constant Mental Drift Can Improve Your Mood and Boost Your Creativity ,” mind-wandering is essential to creativity and problem-solving. “This is how good ideas are born,” he said. When we reflect on memories, imagine what could have happened or how a certain scenario could play out in the future, our brains store this information the same way they do a real experience. And just as our experiences inform our future decisions and ideas, so can these simulations, Bar said.

This is borne out by research. According to a 2017 metastudy , mind-wandering enhances creativity and may play a significant part in problem-solving and learning. Dane and his colleagues found that, for professionals, “problem-oriented daydreaming,” or conjuring thoughts that pertained in some way to the challenges they faced, could be particularly effective in helping them solve problems.

Experiments that Bar and his colleagues conducted suggest that the less stressed we are, the further our minds can roam. The experiments also suggest that, in the absence of significant cognitive demands, original thinking is our “default setting.” When subjects were given a free-association task while being asked simultaneously to perform cognitive tasks of varying levels of difficulty, there was an inverse relationship between mental load and the creativity of their responses. For example, those who had to memorize seven digits gave more predictable responses, while those who had to memorize two digits responded more creatively.

Because mind-wandering promotes creativity, it can also have a positive effect on mood. The more creative you are, the more joy you can experience, and vice versa, Bar said. And both your mood and your level of creativity can enhance — and are enhanced by — the breadth of your thoughts and your openness to experience. Bar called these factors “a cluster that moves together.”

On the other hand, when your mind maintains a more narrow focus between similar thoughts, mind-wandering becomes rumination. And although some degree of rumination is normal, when it becomes chronic, it can lead to depression and anxiety, Bar said.

Mind-wandering can also invite opportunities for serendipity and awe. “The world around us is filled with clues, opportunities and possibilities,” Dane said, but we can take advantage of them only “if we’re able to loosen ourselves from the grip of autopilot.” One way to do that is maybe to put our phones aside; one study found that the presence of participants’ phones limited their cognitive resources, creating a “brain drain.” Although putting your phone down doesn’t guarantee you’ll experience an epiphany, it can help create the right conditions.

Allowing our minds to wander can also give us opportunities to process emotions, Netherton said. Some of her patients keep their brains busy to avoid certain feelings, which then come flooding out when their minds slow down. Providing some time for introspection during the day can help manage those emotions and reduce anxiety. Although mind-wandering has been linked to increased anxiety and depression, the results of a 2019 study suggest that intentional mind-wandering can mitigate anxiety, depression and stress.

Counterintuitively, mind-wandering may also help us get more done. Although we’d never expect our bodies to run all day long, Mecking said, “we somehow expect our brains to be on 24/7.” The high value society places on productivity means we often keep working, even when we notice ourselves slowing down or making mistakes. But by preventing such issues, taking breaks might make us more productive. Meanwhile, Dane points out that, if our minds never strayed from the current task, we wouldn’t remember the other tasks we need to complete. Research shows a link between mind-wandering and the fulfillment of goals.

How to encourage mind-wandering

The way you go about doing nothing or encouraging your mind to wander matters a lot less than the mind-set you bring to the practice, Netherton says. It shouldn’t be something you feel you have to grit your teeth and endure. Rather, she suggests “letting your mind have more freedom.”

Avoid multitasking. “Many people essentially celebrate multitasking itself. And so they might actually feel like they’re doing nothing if they only uni-task,” Dane said. When clients insist they’re too busy to do one thing at a time, he compares the results of uni-tasking to the results of exercise. Generally, exercise energizes us, even if we’re tired before we begin. Similarly, when we’re “in the midst of stormy real life,” stepping away and slowing down allows us to later “engage more thoughtfully and patiently and in a calm manner as we’re being bombarded by stimuli again.”

Put your phone down. Although we know that our phones make it hard, if not impossible, to focus fully on the task at hand, their frequent intrusions have another, less-talked-about downside: keeping our minds from drifting far and wide enough to be “awash in really rich, imaginative, depthful thinking,” Dane said.

Engage your hands. Mecking says doing “something that keeps your hands busy but not stressed out” can help you get in the right frame of mind. A repetitive task such as crocheting or weeding can work, as long as you’re not under pressure to complete it.

Let go of goals. Whatever you do, it can’t be goal-oriented. For example, running could be an excellent way to let your mind zone out if your intention is simply to feel good and get some exercise, Mecking says. On the other hand, if you’re doing a specific workout in preparation for a race and paying close attention to your watch and your effort level, running wouldn’t qualify.

Similarly, driving can offer a chance for your mind to relax — or not. “The morning commute that’s like, ‘Oh my God, I’m late, I’ve got to careen through Starbucks and get back on the highway and traffic’s awful and I’m gritting my teeth,’ is a totally different head space than, ‘I have 30 minutes to sit on the highway or sit on the subway and not have to engage in anything,’ ” Netherton said.

Make a (gentle) commitment to the practice. Although there’s no consensus on how often and how frequently you should engage in the practice of mind-wandering, everyone I spoke with emphasized the importance of making it a part of your daily routine — or at least trying to. According to Mecking, doing nothing shouldn’t be yet another stress-inducing obligation. “I don’t think there’s a way people can fail at doing nothing.”

If guilt is keeping you from easing off the gas pedal, it might make sense to reexamine your values. “Because people value productivity and hard work,” Mecking said, “they feel very, very bad when they do nothing. But what if we started to value free time and leisure, relaxation and doing nothing?”

It's ok to let your mind wander — it's where it goes that makes the difference, science says

How you can promote more positive daydreaming..

Social Sharing

In a productivity-obsessed world, mind-wandering has a bad reputation. The ideal is: focus like a laser beam, blasting to-dos off of your list. Yet, according to psychologists, the average human mind slips the leash of our intentions and spends 30%-70% of its time off-task. It's as though the mind has a mind of its own . That is why there is such a massive market for books, seminars, and products that promise to help us sharpen and sustain our focus, to remain present with the task at hand. Helpful authors offer advice on how to tame the forces, like digital messaging and multitasking which distract us from whatever it is we are trying to do, and to put our attention under tighter control.

But is this really the right strategy? Is mind wandering the enemy? Julie Ji , a psychologist at the University of Western Australia, says that it isn't quite so simple. While a wandering mind can make it more difficult to get things done in the short term, turning our brain loose every now and again also has its benefits. There are good reasons why mind-wandering is so common.

Ji's research focuses on the relationship between the way we think and mental health. According to her, we should not be worried that our mind wanders. But how it wanders matters quite a lot, particularly when we are thinking about the future. That's why I asked Dr Ji to explain what mind-wandering is, what we can learn from our meandering mind, and how we can use this knowledge to better understand and promote our mental wellness.

Mind-wandering is basically defined as the mind being off-task, so it's no wonder it seems like a drag on productivity. In a review of the research on mind-wandering, Jonathan Schooler argues that mind-wandering is associated with lower working memory and sustained attention. However, this is not to say that it's useless. Scientists now believe that when our mind wanders, it can actually do useful and important things. Perhaps the most obvious upside is that it can relieve boredom, and put us in a better mood when our mind wanders into happy territory. Researchers have also found a relationship between creative thinking and mind wandering . In many situations, minds that wander more are better at creative thought than those that maintain more unerring focus.

Research also indicates that one of the most important functions of the wandering mind is to redirect our consciousness to unresolved problems or upcoming goals when it's not needed by present demands. That is, when your mind is not completely engaged in the present, it doesn't mean it's not doing anything. It may be working on upcoming challenges or just directing your attention where it is actually needed, like an unresolved issue. For example, if you are planning a dinner party, you will likely imagine who you will invite, what the table will look like, and what you will serve. As your mind plays through these scenarios like movie clips, it might remind you of everything you need to do to make it happen. According to Brian Levine from McGill University, most of the possible events we imagine in our future actually do end up happening, so the time spent envisioning them may be well-spent.

Because of this planning function, most of our mind-wandering is about the future. And, says Ji, humans are generally optimistic about the future. This positive bias helps us to survive and thrive because it motivates us to go out and do things in the world despite inherent uncertainty and risk. In one study , Ji and her team found that, even when experiencing clinical depression, those who are able to imagine future events having positive outcomes tended to become more hopeful about the future quicker. To continue our dinner party example, when we imagine our friends and family having a great time and imagine the smells coming out of the kitchen, it motivates us to put in the effort to get it all together.

Depression, unsurprisingly, is linked to a greater tendency to have negative thoughts about the future. However, negative future-thinking is not necessarily a bad thing. Imagining negative outcomes can produce emotions that might motivate us to avoid certain situations, and this can be helpful. In many cases we should avoid certain situations or at least find ways to overcome the obstacles that block our way. E.g. if every time you picture your dinner party, you imagine your brother yelling at your crying best friend while the lasagne burns in the oven, maybe you should make some changes to the guestlist and menu.

Therefore, Ji doesn't think that banishing all negative future-thoughts is a good idea, nor is unbridled optimism about the future. It's all about the relative balance between the positive and negative. In a study published in Psychological Research this August, Ji and her team found that depression symptoms were associated with reductions in positive bias when it came to future-oriented mental imagery during mind-wandering. In other words, when the depressed mind imagines the possible future, it loses the rose-tinted lenses through which the healthy minds see the future.

What can we do about this? While research is ongoing, Ji mentioned three things that we can do to promote healthy mind-wandering.

- Be mindful of how your mind wanders: pay attention to where your mind heads when it goes off task. Even when your mind is on the future, it is likely to be oriented by present concerns and problems. If you keep going to the same place, it may be time to do something about it. But also, it would be helpful to notice if your imaginings are primarily positive or negative, since this may signal changes in your emotional wellbeing and have wider implications for your mental health.

- Cultivate your imagination to picture positive experiences in your future: there are two points here. First, it is specifically our imagination and not our verbal thinking that is most closely linked to our emotions. In other words, it's not enough to tell yourself everything is going to be ok; you have to show yourself. Picture it in as much concrete and sensory detail as possible. The idea of positive visualizations of the future has long been used by athletes to improve their performances, and Ji's research suggests that there are also sound mental health reason to do this. When we practice positive imagination consciously, it makes it more likely that we will head there when our mind wanders.

- Put up positive signposts: research shows that how our mind wanders is influenced by environmental cues. For example, right-pointing arrows tend to orient our mind-wandering towards the future, and left-pointing arrows tend to orient it towards the past. In her latest study, not yet published, Dr Ji also found that most positive thoughts occurred when task-unrelated positive words were presented (as opposed to negative or neutral words). Therefore, it is possible that surrounding yourself with cues that are related to positive emotions for you can promote more positive mind-wandering.

Clifton Mark is a former academic with more interests than make sense in academia. He writes about philosophy, psychology, politics, and pastimes. If it matters to you, his PhD is in political theory. Find him @Clifton_Mark on Twitter.

Frontiers for Young Minds

- Download PDF

Mind Wandering Can Be a Good Thing

Staying focused is important for nearly every human activity, yet we often struggle to do it. When we are unable to focus our thoughts, we say that we are mind wandering. Mind wandering is very common and occurs in every healthy mind. In fact, mind wandering may even reflect the regular way of thinking, unless people make special efforts to prevent it. But is all mind wandering the same? Why does the mind wander, and when? What effect does mind wandering have in our lives? In answering these questions, we will show how mind wandering can even be helpful for things like creativity and learning.

Mind Wandering and Its Consequences

Any student knows that it can be hard to keep attention focused. For instance, when you are supposed to be listening to your teacher, you may find your mind drifting away. You might look out the window, make plans for after school, or think about nothing at all! Sadly, if students let their attention drift too far or for too long, they may miss what the teacher is saying—much to the dismay of teachers everywhere!

This experience is very interesting to scientists, many of whom also struggled to focus in school. Sustained attention is the term used to describe the ability to keep focused on whatever activities we are trying to do. We know that sustained attention is very important for many different things—like learning and remembering. We also know that sustained attention often fails and attention shifts to unrelated thoughts—this is called mind wandering [ 1 ]. Mind wandering is surprisingly common. Some studies find that people may spend nearly half their day mind wandering.

The effects of mind wandering can vary a lot. Sometimes there are no effects at all ( Figure 1 ). Think about drinking a glass of water: this task is simple and happens often, allowing you to drink without much effort or spilling, even if your mind is wandering. This kind of behavior is automatic.

- Figure 1 - Mind wandering can occur anytime, anywhere—it is a normal part of the way the brain works.

- Photo by Vanessa Bumbeers on Unsplash .

Other times, mind wandering has minor effects. If you briefly lose focus on your teacher’s voice, you may not hear what was said; but by rapidly focusing on the teacher’s voice again, you can get back on track fairly easily. Finally, there are instances when mind wandering can have very serious results. Imagine crossing the street or riding a bike without focusing on your surroundings.

Because mind wandering is such a common and normal part of daily life, scientists have asked two major questions about it. First, is mind wandering one thing, or are there different kinds? Second, why does mind wandering happen at all?

Question #1: Is All Mind Wandering the Same?

Many studies have tried to discover whether there are different kinds of mind wandering. These studies show that people can lose focus in different ways. Mind wandering can happen on purpose or by accident. Attention can also focus inward (on your thoughts) or outward (on the world around you). Finally, people can lose focus just a little (shallow) or a lot (deep). Do not worry if those sound complicated—we will discuss each one.

The first big difference is whether mind wandering is on purpose or not. Most mind wandering appears to happen on its own, or by accident [ 2 ]. For instance, a surprising sound may capture your attention. Other times, you may just lose focus and have no idea why. That said, mind wandering can also happen on purpose. Consider waiting at a doctor’s office, when you must maintain enough awareness to hear your name being called. At the same time, you will probably allow other thoughts to run through your mind. This “on-purpose” kind of mind wandering is common when doing something easy, or when you do not feel motivated.

Another way of understanding mind wandering is to consider what you are thinking about when you lose focus. This is the difference between internal and external mind wandering [ 3 ]. Perhaps while waiting at the doctor’s office, you start looking out the window to watch people walking by—this focuses on your senses and the world around you and is called external mind wandering . The opposite would be if you focused on your inner thoughts—maybe remembering your last doctor’s visit or planning for what you will do later in the day—and this is called internal mind wandering .

Finally, mind wandering can differ based on how deep vs. shallow it is. One idea [ 4 ] is that there are three levels of mind wandering. The deeper your level of mind wandering, the less connected you are to the world around you. Think of mind wandering as a slinky bouncing down stairs. Unless something stops it, the mind will keep going from shallow mind wandering (the top steps) into the deeper kinds (bottom steps).

The first, most shallow step in mind wandering involves very short and shallow dips in your attention to detail. This is relatively common, like briefly zoning out during class. The effects, however, are usually small. People will usually notice they are mind wandering and choose to refocus their attention.

If attention is not refocused, it is likely that mind wandering will progress to the second, medium, level. This involves longer-lasting lapses in attention, which you are less likely to notice. When mind wandering at this medium depth, you can still go through the motions of activities that are familiar to you, like brushing your teeth or eating a meal. These activities are a kind of automatic responding—like a robot that is programmed to do some task but is not really thinking. When the robot makes a mistake, it continues with whatever it was programmed to do.

The final and deepest level of mind wandering involves paying the least attention to the surrounding world. It is marked by the most extreme changes in behavior, like blank stares and missing what others say. In this deeper level, attention is directed internally, or to nowhere at all, which is called mind blanking . This level is most likely to result in serious consequences, like if you are riding a bike or learning to drive ( Figure 2 ).

- Figure 2 - Mind wandering can be dangerous, depending on the activity you are participating in.

- For example, failure to maintain focus while biking could lead to a crash. Shallow mind wandering is less risky (you can likely refocus) but deeper mind wandering is far more dangerous. Photo by William Hook on Unsplash .

In sum, different kinds of mind wandering exist. Despite these differences in the types of mind wandering, a common finding is that people struggle with whatever they are doing when the mind wanders [ 5 ].

Question #2: Why Does Mind Wandering Happen?

Much evidence suggests that mind wandering is not a rare mistake, but actually a very normal part of the way the mind works! In other words, the mind will naturally wander unless it is given a specific job [ 2 , 6 ]. In fact, we now know that attention-related disorders like ADHD can be understood as a normal behavior (mind wandering) that is simply happening in an unusually high amount. This knowledge makes it easier to study how much mind wandering is normal and how mind wandering can impact other parts of life, such as emotions and learning [ 7 ].

So why do we mind wander in the first place? The likely reason is that mind wandering serves useful purposes. For instance, mind wandering can help in problem solving, creative thinking, and planning for the future [ 8 ]. Even when you are not trying to think about anything, your mind is still working in the background. Without trying, your mind might start focusing on memories that could help solve a problem in the present. This can be when creative or unusual ideas are made! For instance, a musician might combine different melodies to make something new.

Also, mind wandering can help with learning and memory—specifically for things that are not relevant to the task at hand [ 5 , 8 ]. People who mind wander more show greater learning for this irrelevant information, and the learning is best during periods of mind wandering [ 9 ]. After learning, mind wandering helps strengthen recent memories. This benefit is strongest when the memories are relevant to you personally.

Finally, mind wandering offers a time to “rest” and prepare for upcoming thinking [ 8 , 10 ]. It prevents new information from entering the mind and using up limited attention in processing that new information. When our minds wander, we can then process older information in new ways. Creative ideas can be built and used to plan or solve problems. When our minds wander, our attention can also focus on sources of information that are potentially useful, like thinking about plans for later in the day, for example. When that information is useful, it can be processed and remembered.

The mind actually does a lot when it wanders! So, do not see mind wandering as a mistake. Try to remember how mind wandering redirects your focus. This allows you to learn new things and to process information better. There are times when you should try to focus your attention, like when riding a bike. However, always remember that taking a mental break is healthy. There are many wonderful things in the world that you can notice when you let your mind wander. So, let yourself gaze out the window or stare at clouds, or even close your eyes and simply “be”.

Sustained Attention : ↑ The ability to focus attention while ignoring distractions, over time.

Mind Wandering : ↑ Thinking about anything other than the task you should be focusing on.

External Mind Wandering : ↑ Focusing attention on the world around you, through your senses (sight, sound, and more).

Internal Mind Wandering : ↑ Focusing attention on your inner thoughts, such as recalling memories or planning for the future.

Mind Blanking : ↑ When the mind is not active, and attention is not focused on any particular thoughts.

ADHD : ↑ Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; a mental health disorder involving many instances of mind wandering.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

[1] ↑ Cheyne, J. A., Solman, G. J. F., Carriere, J. S. A., and Smilek, D. 2009. Anatomy of an error: a bidirectional state model of task engagement/disengagement and attention-related errors. Cognition 111:98–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.12.009

[2] ↑ Thomson, D. R., Besner, D., and Smilek, D. 2015. A resource-control account of sustained attention: evidence from mind-wandering and vigilance paradigms. Perspect. Psychol. Sci . 10:82–96. doi: 10.1177/1745691614556681

[3] ↑ Smallwood, J., and Schooler, J. W. 2006. The restless mind. Psychol. Bull . 132:946–58. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.946

[4] ↑ Cheyne, J. A., Carriere, J. S. A., and Smilek, D. 2009. Absent minds and absent agents: attention-lapse induced alienation of agency. Conscious Cogn . 18:481–93. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2009.01.005

[5] ↑ Blondé, P., Girardeau, J. C., Sperduti, M., and Piolino, P. 2022. A wandering mind is a forgetful mind: a systematic review on the influence of mind wandering on episodic memory encoding. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev . 132:774–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.11.015

[6] ↑ Ralph, B. C. W., Smith, A. C., Seli, P., and Smilek, D. 2019. Yearning for distraction: evidence for a trade-off between media multitasking and mind wandering. Can. J. Exp. Psychol . 74:56–72. doi: 10.1037/cep0000186

[7] ↑ Mowlem, F. D., Skirrow, C., Reid, P., Maltezos, S., Nijjar, S. K., Merwood, A., et al. 2019. Validation of the mind excessively wandering scale and the relationship of mind wandering to impairment in adult ADHD. J. Atten. Disord . 23:624–34. doi: 10.1177/1087054716651927

[8] ↑ Schooler, J. W., Smallwood, J., Christoff, K., Handy, T. C., Reichle, E. D., and Sayette, M. A. 2011. Meta-awareness, perceptual decoupling and the wandering mind. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15:319–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.05.006

[9] ↑ Decker, A., Dubois, M., Duncan, K., and Finn, A. S. 2022. Pay attention and you might miss it: greater learning during attentional lapses. Psychon. Bull. Rev . 30:1041–52. doi: 10.3758/s13423-022-02226-6

[10] ↑ Litman, L., and Davachi, L. 2008. Distributed learning enhances relational memory consolidation. Learn Mem . 15:711–6. doi: 10.1101/lm.1132008

Why Mind Wandering Can Be So Miserable, According to Happiness Experts

We still don’t know why our minds seem so determined to exit the present moment, but researchers have a few ideas

Libby Copeland

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/85/b5/85b5d6a1-2bd8-4e03-9c25-ad9d7b9a9c69/s08pdg.jpg)

For you, it could be the drive home on the freeway in stop-and-go traffic, a run without headphones or the time it takes to brush your teeth. It’s the place where you’re completely alone with your thoughts—and it’s terrifying. For me, it’s the shower.

The shower is where I’m barraged with all the “what-ifs,” the imagined catastrophes, the endless to-do list. To avoid them, I’ve tried everything from shower radio and podcasts to taking a bath so I can watch an iPad. I’ve always thought this shower-dread was just my own neurosis. But psychological research is shedding insight into why our minds tend to wander without our consent—and why it can be so unpleasant.

Scientists, being scientists, sometimes refer to the experience of mind-wandering as “stimulus-independent thought.” But by any name, you know it: It’s the experience of arriving at work with no memory of the commute. When you’re engaged in mundane activities that require little attention, your brain drifts off like a balloon escaping a child’s hand—traveling to the future, ruminating on the past, generating to-do lists, regrets and daydreams.

In the last 15 years, the science of mind wandering has mushroomed as a topic of scholarly study, thanks in part to advances in brain imaging. But for a long time, it was still difficult to see what people’s brains were doing outside the lab. Then, when smartphones came on the scene in the late 2000s, researchers came up with an ingenious approach to understanding just how often the human brain wanders in the wilds of modern life.

As it turns out, our brains are wily, wild things, and what they do when we’re not paying attention has major implications for our happiness.

In 2010, Matt Killingsworth, then a doctoral student in the lab of happiness researcher Daniel Gilbert at Harvard University, designed an iPhone app that pinged people throughout the day, asking what they were experiencing at that very moment. The app asked questions like these, as paraphrased by Killingsworth:

1. How do you feel, on a scale ranging from very bad to very good?

2. What are you doing (on a list of 22 different activities, including things like eating, working and watching TV)?

3. Are you thinking about something other than what you're currently doing?

Killingsworth and Gilbert tested their app on a few thousand subjects to find that people’s minds tended to wander 47 percent of the time. Looking at 22 common daily activities including working, shopping and exercising, they found that people’s minds wandered the least during sex (10 percent of the time) and the most during grooming activities (65 percent of the time)—including taking a shower. In fact, the shower appears to be especially prone to mind wandering because it requires relatively little thought compared to something like cooking.

Equally intriguing to researchers was the effect of all that mind wandering on people’s moods: Overall, people were less happy when their minds wandered. Neutral and negative thoughts seemed to make them less happy than being in the moment, and pleasant thoughts made them no happier. Even when people were engaged in an activity they said they didn’t like—commuting, for example—they were happier when focused on the commute than when their minds strayed.

What’s more, people’s negative moods appeared to be the result, rather than the cause, of the mind wandering. Recently, I asked Killingsworth why he thought mind wandering made people unhappy. “When our mind wanders, I think it really blunts the enjoyment of what it is that were doing,” he told me.

For most, the shower in and of itself is not an unpleasant experience. But any pleasure we might derive from the tactile experience of the hot water is muted, because our minds are elsewhere. Even when our thoughts meander to pleasant things, like an upcoming vacation, Killingsworth says the imagined pleasure is far less vivid and enjoyable than the real thing.

Plus, in daily life we rarely encounter situations so bad that we really need the mental escape that mind wandering provides. More often, we’re daydreaming away the quotidian details that make up a life. “I’ve failed to find any objective circumstances so bad that when people are in their heads they’re actually feeling better,” Killingsworth told me. “In every case they’re actually surprisingly happier being in that moment , on average.”

When I told Killingsworth I spend my time in the shower imagining catastrophes, he wasn't surprised. More than a quarter of our mental meanderings are to unpleasant topics, he’s found. And the vast majority of our musings are focused on the future, rather than the past. For our ancestors, that ability to imagine and plan for upcoming dangers must have been adaptive, he says. Today, it might help us plan for looming deadlines and sources of workplace conflict.

But taken to an extreme in modern day life, it can be a hell of an impediment. “The reality is, most of the things we’re worrying about are not so dangerous,” he said.

In some cases, mind wandering does serve a purpose. Our minds might “scan the internal or external environment for things coming up we may have to deal with,” says Claire Zedelius , a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California at Santa Barbara who works in the lab of mind wandering expert Jonathan Schooler . Mind wandering may also be linked to certain kinds of creativity , and in particular to a creativity “incubation period” during which our minds are busy coming up with ideas, Schooler’s lab has found.

It’s unclear how our tendency to drift is affected by the diversions and distractions of our smartphones. As Killingsworth pointed out, all those distractions—podcasts, email, texts and even happiness trackers—may mean we’re effectively mind wandering less. But it may also be that “our capacity to direct our attention for sustained periods gets diminished, so that then when we’re in a situation that’s not completely engaging, maybe we have a greater propensity to start mind wandering.”

I took up mindfulness meditation a few years ago, a practice which has made me much more aware of how I’m complicit in my own distress. For about 15 minutes most days, I sit in a chair and focus on the feeling of my breath, directing myself back to the physical sensation when my mind flits away. This has helped me notice how where I go when I mind wander—away from the moment, toward imagined future catastrophes that can’t be solved.

Cortland Dahl , who studies the neuroscience of mind wandering and has been meditating for 25 years, told me that he was six months into daily meditation practice when he witnessed a change in the way he related to the present moment. “I noticed I just started to enjoy things I didn’t enjoy before,” like standing in line, or sitting in traffic, he says. “My own mind became interesting, and I had something to do—‘Okay, back to the breath.’” Killingsworth’s findings help explain this, said Dahl, a research scientist at University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Center for Healthy Minds.

“We tend to think of suffering as being due to a circumstance or a thing that’s happening—like, we’re physically in pain,” he says. “And I think what this research points to is that oftentimes, it’s not actually due to that circumstance but much more to the way we relate to that.”

Killingsworth is still gathering data through Trackyourhappiness.org , which now has data from more than 100,000 people, and he plans to publish more papers based on his findings. He says the lesson he’s taken from his research so far is that we human beings spend lots of time and effort fixing the wrong problem. “A lot of us spend a lot of time trying to optimize the objective reality of our lives,” he told me. “But we don’t spend a lot of time and effort trying to optimize where our minds go.”

A few months ago, I decided to try mindful showering. If I could observe the mental script and divert myself back to breath during meditation, I figured, perhaps I could divert myself back to the present moment while washing my hair. Each time I do it, there’s a brief moment of dread when I step into the shower without a podcast playing. Then, I start to pay attention. I try to notice one thing each time, whether it’s the goose bumps that rise when the hot water first hits, or the false urgency of the thoughts that still come. They demand I follow them, but they’re almost always riddles that can’t be solved.

The trick is in recognizing the illusion— ah yes, there’s that ridiculous clown car of anxiety coming down the road again. The saving grace, when I can manage to focus, is the present moment.

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

Letting Your Mind Wander

What are the pros and cons of mind-wandering.

Posted April 15, 2013

- Understanding Attention

- Take our ADHD Test

- Find a therapist to help with ADHD

I was trying to daydream but my mind kept wandering. Steven Wright