Home > Sports > List > Cycling > Fitness > Testing > Anthropometry > Tour de France

Body Size of Cyclists in the Tour de France

There are many physiological factors which are important for success in cycling , particularly leg power and aerobic endurance. Body size also plays a part, as it is the muscular power and aerobic endurance capacity proportional to body weight (power to weight ratio) that is important.

Successful cyclists are generally exceedingly lean, with skinny arms and big muscular thighs. Elite cyclists have also been found to have proportionally longer femurs, which gives them extra leverage when they push the pedals. Among the road racers, the climbers tend to be lighter and smaller than the sprinters and time trialists. The Tour de France is almost always won or lost on mountain climbs, so successful riders in this event will need to fit the mold somewhere between the great climbers and time trialists.

As cyclists have become more professional over the years and training and diet more fine-tuned to maximize performance, has this been reflected in the body size of the elite cyclist? Here we look at historical anthropometrical data of the participants of the Tour de France, the premier tour event which attracts the greatest of riders from around the world, and look for trends in changes in these parameters and relate them to the performance of the cyclists.

Tour de France Cyclists Stats

There is limited historical anthropometrical data of Tour de France cyclists available, though the height and weight of all participants in recent years have been collated by the procyclingstats website, and the height and weight of many of the winners can be found online going back to at least the 1940s.

We have analyzed the age, height and weight data of all participants in the Tour de France since 1990, and the age, height and weight of the winners going back to the 1940s (up to 2019). Using these height and weight measures, we have calculated the average BMI measurement , which is a general (though somewhat flawed) measure of leanness.

Riders are Getting Older and Thinner

The general findings of our anaylysis is that the participants in the Tour de France on average have been getting older, however riders can still win at any age - case in point the 2019 winner was only 22 years old, well below the average winner's age of 28. Again in 2020 there was a young winner, Tadej Pogačar also 22 years old. The average height of riders has not varied much, though riders are much leaner than they were once, reflected in a lower weight and body mass index.

We discuss each of these parameters below in more detail. See also the original data tables .

Age of Tour de France Cyclists

The average age of all cyclists from each tour has gradually increased since it was first recorded, rising from an average of about 28 years to nearly 30 years now, shown clearly in the graph below. Such an increase in age may be due to advances in medicine, diet and training keeping the riders in top condition, but also due to the increasing monetary rewards providing the incentive for them to keep competing for longer.

We have data about the age of the winners for all tours. This data does not show such a clear increase as does the average data, it more so demonstrates the wide variation in ages. The average age of the tour winner is 28 years, ranging from the youngest Henri Cornet winning in 1904 at only 20 years of age, the oldest Firmin Lambot winning in 1922 aged 36.

In recent years, the winners were generally above the average age, being experienced riders in their early thirties. However, the winner of the 2019 tour was only 22 years old, the youngest winner of the Tour de France since World War II. Also the 2020 and 2021 winner Tadej Pogačar was 21 and 22 years old respectively.

Height of Tour de France Cyclists

The average height of all cyclists from each tour since 1990 is mostly between 1.80m and 1.82m. The anomalous average height of 1.86m in 1993 skews the data, which shows otherwise a fairly consistent average height. This data was taken from that published by procyclingstats, and their database from the 1990s may not have included all the riders, so may not be as representative of the whole group as more recent averages.

The tallest rider on record is Marcel Sieberg at 1.98 meters (6' 6"), who rode in the Tour de France nine times between 2007 and 2018. The winner of the first-ever race in 1903, Maurice Garin, was only 1.62 m (5' 4"), though the shortest may be Samuel Dumoulin at 1.59 meters (5' 3") who rode in the Tour de France 12 times between 2003 and 2016.

A professional cyclist who literally stands out among his peers is Irishman Conor Dunne, who races for Aquablue. He is yet to ride in the Tour de France, but if he does you will notice his 2.04m tall frame which absolutely towers over his fellow riders.

The graph below of the winner's height for each tour since 1947 shows a general trend of increasing height. The winners in the last decade have been particularly taller, above the average of the peloton - except in 2019! Egan Bernal, who was the youngest winner of the Tour de France since World War II, bucked the trend in height as well and was only 175m tall. The tallest Tour de France winner was Bradley Wiggins at 1.90m (6'3"), and there are also a few tall recent winners at 1.86m (6'1") - Chris Froome, Andy Schleck and Miguel Induráin.

Weight of Tour de France Cyclists

Since 1990, the average weight of all cyclists in the Tour de France has decreased, though seeming to plateau in the last 10 years. There has been a drop in the average weight of about 5 kg (11lbs) over that time, with no significant difference in height - which would indicate that the riders are getting slimmer.

The heaviest rider on record is Magnus Backstedt at 95 kg (209.5 lbs). The lightest, Leonardo Piepoli at 57 kg (125.7lbs).

Below is the graph of the winner's body weight for each tour. Since 1945, there is great variation, though there is no trend of significant changes (unlike the decrease in average rider weight shown in the last 30 years).

The 1973 winner, Luis Ocaña, was just 52 kg (115 lbs). At the other end of the scale, Miguel Induráin was recorded at 80kg (176 lb).

BMI of Tour de France Cyclists

As mentioned above, it is the power to weight ratio that is very important for cyclists, which is maximized by having low body fat levels. The body mass index (BMI), which relates weight to height, is a general indication of body fat levels. The graph of the average BMI of all cyclists from each tour since 1990 shows a clear decrease, a reflection of the decreasing average body weight while the height has not changed - therefore the riders are getting thinner.

The BMI of the winners since 1947 also shows a tendency to get lower over time. The 2012 winner Bradley Wiggins had a BMI of only 19.1, as did Luis Ocaña, the winner from 1973 winner. The heights of these two riders were very different (1.90 m v 1.65 m) but obviously they both carried very little bodyfat.

Olympic Cycling

At the 2012 Olympic Games, the averages of the road cyclists were 180.5cm and 70.8 kg, with an average BMI of 21.7.

Selected References

- Foley, J. P., Bird, S. R., & White, J. A. (1989). Anthropometric comparison of cyclists from different events. British journal of sports medicine, 23(1), 30–33.

Related Pages

- Fitness testing for cycling

- Anthropometry for cycling

- Olympic Games Anthropometry for other sports in 2012

- Athlete Body Size Changes Over Time

- All about fitness testing , including anthropometry testing

- Poll about the fitness components for cycling

- How to measure Height and Weight , and calculate BMI measurement

Search This Site

More cycling.

- Cycling Home

- Fitness Testing

- Tour de France

- Cyclist Profiles

Sport Extra

Check out the 800+ sports in the Encyclopedia of Every Sport . Well not every sport, as there is a list of unusual sports , extinct sports and newly created sports . How to get on these lists? See What is a sport? We also have sports winners lists , and about major sports events and a summary of every year .

T.E.S. Latest

- Trisome Games

- Possible Future Olympic Sports

- Sporting Stadium Seating

- POLL: What's Your Favorite Olympic Sport

Current Events

- US golf Masters

- Kentucky Derby

- French Open

- Paris Olympics

- 2024 Major Events Calendar

Popular Pages

- Super Bowl Winners

- Ballon d'Or Winners

- World Cup Winners

Latest Sports Added

- SUP Jousting

- Virtual Golf

home search sitemap store

SOCIAL MEDIA

newsletter facebook X (twitter )

privacy policy disclaimer copyright

contact author info advertising

I tried eating like a Tour de France rider for a day - here’s how I coped with the huge calorie intake

The mountains of food Tour de France riders have to chomp through are nearly as daunting as the cols themselves. I tried to find out what is it actually like to eat for a Tour de France stage

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

Fuelling on the stage

Homemade on-the-bike snack recipe, post-stage refuelling.

A 70kg rider pedalling hard burns approximately 1,000kcal per hour. Riders in this year’s Tour de France will cover 3,405km, and if we assume an average speed of 40kph, that’s 85 hours of riding – burning in the region of 83,000kcal, or 4,000kcal per stage. That’s a very rough estimate, of course, and doesn’t take into account the ‘tickover’ energy needed to keep the body functioning 24/seven, but it hammers home the magnitude of the eating challenge: 83,000kcal is the equivalent of 64kg of pasta or 44 loaves of bread – literally gut-busting quantities of food that the pros have to eat to compete in the Tour de France . I wanted to find out how they do it and just how difficult it is to keep up with the vast energy demands of the race. So I decided to find out – by fuelling like a pro for a day.

Rather than sitting on the couch ordering takeaways all day, I would mimic a Tour de France competitor’s fuelling while riding the equivalent of a demanding stage. I had neither the time nor budget to do this experiment in France on an actual route from the race (sob!), so I needed to choose a stage I could replicate on the Northern English parcours on my doorstep. Stage 10 from the 2022 edition of the Tour de France, from Morzine to Megève looked ideal: a relentlessly hilly 148km.

I would start in my home town of Otley in Yorkshire, head out through Ikley, then up into Skipton before taking on the steep slopes of Malham; turning for home, I’d make my way up over Greenhow and across the moors to finish. This would mean covering 143km, just 5km short of Stage 10’s distance. Admittedly, no Yorkshire climb was going to replicate Stage 10’s finale (1,384m) but adding together all my smaller ascents, I would accrue just as much overall elevation, a total of 8,225ft (2,507m).

Carb load

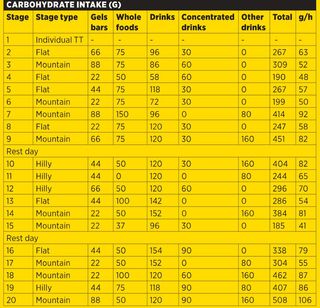

Sport Performance & Science Reports published a paper entitled ‘Case Study: The application of daily carbohydrate periodisation throughout a cycling Grand Tour’ – showing exactly how much carbohydrate a pro rider in the 2021 Vuelta a España consumed on each stage, casting a light on the vast energy requirements of a Grand Tour.

The study’s subject, an unnamed 26-year-old rider, consumes a staggering 843g of carbohydrates a day on average, peaking at 1,100g on the most demanding day – equivalent to 4kg of cooked rice. I’d need to consume between eight and 12g of carbs per kilo of bodyweight; in other words, I was going to have to stuff my face like never before.

Why are such huge helpings of starchy foods vital for a stage racer? “Carbohydrates are king for endurance,” advised Will Girling, team nutritionist for EF Education-EasyPost. “They are the primary energy source when cycling at anything above a moderate effort. Ensuring riders have a high carb intake throughout the race not only aids performance but has been shown to improve recovery after cycling too.” While carb requirements vary day to day depending on the length and profile of the stage, protein remains consistent. “ Protein intake doesn’t fluctuate, it is always at a minimum of two grams per kilo of body weight,” added Girling. As for fat: “We try to stay at the lower end, but it’s usually between one and two grams per kilo of bodyweight a day.”

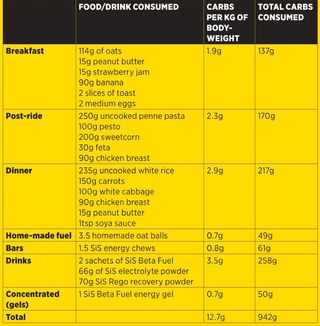

On the morning of my ride, I weighed in at 74.1kg, and decided to aim for the upper end of the intake guidelines, 12.7g of carbs per kilo, meaning I’d need to eat a total of 943g – nearly a full kilo of pure carbs. My next job was to break this down into breakfast, on-bike and post-ride fuelling. What shocked me most was just how much carbohydrate I would need to consume in liquid form.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Tallying up the intake

“Trying to hit 90-100g of carbs per hour can be very difficult on solid food,” explained Girling. “The bulky nature of it, and the process of chewing, increases the feeling of fullness. You just can’t get that amount of solid food down on the bike.” This is even more difficult if the racing is aggressive and the effort level high.

To make my challenge as realistic as possible, I would ride as hard as possible while consuming two sachets of Science in Sport (SiS) Beta Fuel 80 (160g of carbs) on the bike.

I started the day with porridge, my usual race day breakfast, keeping in mind Girling’s caution that “it’s important to not feel really full or stuffed” before you start riding. The best way to side-step the overfilling problem, he advised, was to add extra carbs in the form of sugary toppings such as maple syrup or honey. I decided to stick to what I knew and added a dollop of peanut butter and strawberry jam to my porridge.

To help me keep an accurate tally of my cycling nutrition , I used the MyFitnessPal app, and weighed out all my portions. Here’s the breakdown of what I ate across the day:

My porridge amounted to 78g of carbohydrates, so I still needed an extra 60g. Scrambled eggs on two slices of toast, followed by a large banana, and finally I was there: 134g of carbs were in my belly. Feeling slightly uncomfortably full, I gave myself two hours to let everything digest.

0 - 50km: Otley to Skipton

Imagining myself in the peloton and settling into the race, I pushed on at a tempo of around 300 watts over the opening 25km of rolling hills, eating three homemade oat balls (see recipe below) 20 minutes apart. Over the first hour, I consumed 60g of carbs in total, 30g from liquid, 30g from solid food. To stay hydrated, I aimed to consume 500ml of water per hour.

After 40km I’d already climbed about 1,000ft, and now pushed on up over the first proper climb of the day to the top of the Cringles. In my imaginary Stage 10, this is where the break was likely to go, so I tightened up my shoes and put the power down. The intensity was too high to eat solid fuel now, so over the next hour I drank a bottle of Beta Fuel containing 80g of carbs.

51 - 100km: Skipton to Grassington

Malham Cove loomed in the distance: a climb of 2.6km at an average gradient of 7% – arguably the toughest part of the ride. Still trying to distance the imaginary peloton, I kept the power high and stuck to the nutrition plan, eating one and a half SiS Beta Fuel chews (46g of carbs per chew), washed down with water. Mixing up the textures and flavours definitely helped keep my appetite interested.

The grind up and over Malham out of the way, I headed into the Dales, and was finally riding with the wind, a welcome relief after 2.5 hours of headwind. But now I was heading into unknown territory in terms of my endurance. Though I’m used to long rides of over 3.5 hours, I usually do them at low intensity - training zone wise that’d be Zone 2 - whereas now I was pushing hard. This is where fuelling would make all the difference, and so far I’d stuck to the plan: 90g the first hour, 80g in the second and 70g in the third hour.

In the fourth hour, I drank another bottle of SiS electrolyte mix, ate half a homemade bar and one Beta Fuel energy gel . I wasn’t feeling hungry at all and was grateful that I only had a few bites of solid food left. The temperature had climbed to 17ºC – tropical for Yorkshire – so drinking the liquid carbs wasn’t a problem.

101-143km: Grassington to Otley

After a long, gradual drag up onto the moors, Greenhow hove into view, and my stage win fantasy was entering its critical phase. On the downhill before the final ascent of the day, I popped another gel, grabbed my final bottle of Beta Fuel and raced into the final 40 minutes. This would be the real test, the point where the stage is won or lost.

I was pleasantly surprised, my legs still felt relatively fresh given the four-and-a-quarter hours of hard effort, and I was able to get out of the saddle and dance on the pedals as I unleashed everything towards the finish line. Done. I’d ridden 143km, climbed 8,225ft, and more importantly I’d consumed 399g of carbs. It had taken 4.5 hours and I’d burnt almost exactly 5,000kcal while averaging 284W (309W normalised) for an average speed of 31.5kph (19.6mph).

My favoured on-bike fuel for my ride were these homemade oat balls, taken from Volume 2 of The Cycling Chef by Alan Murchison. They are named ‘Cheryl’s coconut oat balls’ because the recipe was ‘borrowed’ from a British Cycling soigneur. I loved the subtle flavour, and they were really easy to eat on the bike.

INGREDIENTS

- 200g oats

- 150g dates

- 100g honey

- 100g peanut butter (or any nut butter of your choice)

- 15g chia seeds

- 15g desiccated coconut

- 2g salt

1) Add oats and dates to a blender and blend into a paste.

2) Add the other ingredients and beat it all together.

3) Roll the mixture into 40g balls (making approx 14).

4) Store in an airtight container in the fridge.

Looking for more on-bike nutrition snacks? Here’s how to make Superseed Flapjacks and Veggie Rice Balls - and you can find even more homemade energy bar recipes over here.

In a real Grand Tour, my ride would have been just one of 21 stages, and crucial now, having finished, would be the replenishment of my glycogen stores, as well as taking on enough protein for muscle repair. Following the recommendations, I now needed to eat a further 208g of carbohydrates. “Riders have a recovery drink and quick-release carbohydrates,” Girling said. “The form varies day to day; some riders like sweets like Haribo, others prefer a sugary drink.” I opted for a bottle of chocolate-flavour SiS Rego recovery drink, which gave me 24g of protein and 38g of carbs, before then refuelling with real food .

For my post-ride meal, to be eaten as soon as I’d showered and changed, I opted for 250g (raw weight) of pasta with some pesto, chicken and sweetcorn. This was arguably the biggest challenge of the day, as I just wasn’t feeling hungry. After much slow chewing and resentful staring at my fork, the bottom of the bowl eventually came into sight.

Food fatigue and repetition can be a real problem for riders, and I began to understand why. Eating was the last thing on my mind as dinnertime approached. For my biggest meal of the day, I was expected to eat a whopping 217g of carbs – almost three grams per kilo of body weight. How do pro riders manage it? “We rotate themes,” Girling told me. “Mexican food one night, Japanese the next, then perhaps local cuisine from the area – whatever it takes to keep it interesting and appetising.” Heeding Girling’s final tip, “learn to love rice”, I cooked myself a chicken stir-fry.

Behind the scenes

It’s the challenge you don’t see taking place behind the scenes of the Tour: nutritionists and chefs making sure their riders are getting enough carbs and calories . Across the single day of my challenge, I consumed a total of 942g of carbs and 5,726kcal, which still left me with a deficit of 1,800kcal. If I did that over a few days, the diminishing energy reserves would soon take their toll.

Aside from energy requirements, how do the pros make sure they’re getting all the vitamins and minerals they need? “Most take a multivitamin, which covers all bases, an omega-3 supplement to help with recovery , a probiotic to boost immunity and gut function , as well as whey protein, and tart cherry juice to help with inflammation.” All of these are worth considering to “help support overall health,” Girling suggested.

It’s been an eye-opening experience as an amateur rider to eat like a WorldTour pro for a day. My usual training volume is around 15 hours a week, and I rarely consume more than 20g of carbohydrates per hour on the bike. Reflecting on how strong I felt on my Stage 10 simulation ride, while consuming vastly more carbs, has taught me a lesson. I’ve realised that there are times – such as in the fourth hour of an endurance ride or in the final set of intervals – when I could benefit from taking on more fuel. It’s not every day I’ll need to consume 5,500kcal, of course, but I’ll certainly be thinking more carefully about the amount of nutrition my rides and races really demand.

This full version of this article was published in the print edition of Cycling Weekly. Subscribe online and get the magazine delivered direct to your door every week.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Tom Couzens is a racing cyclist currently representing The Ribble Collective on the road and the Montezumas cyclo-cross team off road. His most notable results include winning the Monmouth GP national series race as a junior; finishing sixth in the 2022 British National Cyclo-cross Championships; and he was selected to represent Great Britain at the European Cyclo-cross Championships in 2020/21. Tom draws on his high-level racing experience and knowledge to help Cycling Weekly readers maximise their potential and get as much as possible out of their riding.

British rider was a late addition to the Ineos Grenadiers team for the race across the pavé

By Tom Thewlis Published 7 April 24

Can reframing your pain help you push yourself harder, faster and for longer?

By Hannah Bussey Published 7 April 24

Useful links

- Tour de France

- Giro d'Italia

- Vuelta a España

Buyer's Guides

- Best road bikes

- Best gravel bikes

- Best smart turbo trainers

- Best cycling computers

- Editor's Choice

- Bike Reviews

- Component Reviews

- Clothing Reviews

- Contact Future's experts

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Advertise with us

Cycling Weekly is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site . © Future Publishing Limited Quay House, The Ambury, Bath BA1 1UA. All rights reserved. England and Wales company registration number 2008885.

Tour de France: FAQs

2022 tour de france, kreativefolks, january 27, 2023, how long is the 2020 tour de france.

The Tour de France’s 109th edition covers a total distance of 3328 kilometers (2068 miles), making it the second-longest of the three Grand Tours in 2022, after the Giro d’Italia (3410.3 kilometers) (La Vuelta a Espana is the shortest at 3280.5km).

How long is each day of the Tour de France?

Nine flat stages, three hilly stages, seven mountain stages (including five summit finishes), two individual time trials, and two rest days make up the Tour de France. Every day, one stage is run, which spans around 225 kilometers and takes about five and a half hours to complete.

How do you win the Tour de France?

After 21 stages, the cyclist with the best overall time wins. Each day, a stage winner is determined by the first racer to cross the finish line.

How long is each race in Tour de France?

Each stage, or racing day, varies in length from 32 to 141 kilometers. The Tour’s itinerary varies from year to year, but certain iconic towns are always included.

Do Tour de France riders sleep?

On TV, you’ll frequently see them come to a halt en masse for a “nature break.” Then they’ll sleep at night because the phases are specified in length and they’ll all be staying in a hotel.

What was the longest Tour de France stage?

The longest Tour de France stage on record was the fifth stage in 1920, which was 482 kilometers (300 miles) long! Stages are currently averaging 175km / 109mi in length. Stage 3 is the longest this year, measuring 198 kilometers / 123 miles

What is a peloton?

The peloton, sometimes known as the “pack” or “bunch,” is the largest group of cyclists on the route. A rider consumes 30% less energy when riding in a group than when riding alone. A following peloton usually has the upper hand over a smaller escape group.

How many hours a day do Tour de France riders ride?

Feeding the world’s best riders during a Grand Tour is no easy task, with riders spending up to six hours a day on the bike with little time for recovery and only two rest days over the course of the event. “To fuel the journey riders need to consume an average of 5,000-plus calories per stage,” says one rider.

Are females allowed in the Tour de France?

The 2022 Tour de France Femmes, a widely anticipated new stage race for professional women, was announced at the event. From 2014 through 2021, the eight-day Tour de France Femmes will replace the single-day La Course by le Tour de France, which was conducted in various sites across France.

What is an echelon?

When the peloton is buffeted from the side, the riders form smaller angled formations to take advantage of each other’s draught. Echelons form a formation similar to that of flying geese, however the size of each echelon is regulated by the width of the road. In crosswinds, smart riders can employ echelons to put distance between themselves and their opponents.

What is a domestique?

A rider who puts his personal objectives aside in order to help his teammate. A domestique rides into the wind to protect his team leader, as well as carrying extra water bottles and snacks. If the leader suffers a puncture, the domestique has the option of abandoning his wheel or bicycle and waiting for the leader to rejoin the peloton.

What is the gruppetto?

During mountain stages, a group of riders forms towards the back of the race. They only ride fast enough to make the cutoff time for the day, which is based on a percentage of the winner’s time. Sprinters, wounded or sick cyclists, and riders wanting to conserve energy for the next day are frequently found in the gruppetto.

What is the purpose of the Publicity / PR caravan?

The PR caravan, a two-hour-before-the-race display of sponsor-emblazoned cars and floats, runs the entire route, handing away millions of souvenirs and sweets to the supporters along the way.

What is the fastest time for the Tour de France?

Rohan Dennis’ stage 1 of the 2015 Tour de France in Utrecht is the fastest time trial, with an average speed of 55.446 km/h (34.5 mph). In a team time-trial, the 2013 Orica GreenEDGE team won the quickest stage. At 57.7 km/h, they completed the 25 km time trial (35.85 mph).

How hard is Tour de France?

The Tour de France is often regarded as one of the world’s most arduous and tough sporting events. Cyclists strain their bodies to the limit for 21 stages over 23 days, day after day, after day, after day.

What is the race caravan?

The peloton is preceded and followed by a long line of team vehicles, broadcast and photographer motorcycles, and race official cars. Riders will return to team trucks for food, clothing, or mechanical assistance, and then slowly exit the vehicles to rejoin the peloton.

What is the broom wagon?

The vehicle that follows the Tour and “picks up” riders who drop out during a stage.

How do cyclists pee whilst racing the Tour de France?

Some cyclists prefer not to urinate on the bike, while others seek assistance in the form of a teammate pushing them from behind so they can maintain momentum while pedalling.

What is hors catégorie?

Climbs in the Tour de France are divided into categories based on their length, steepness, and location throughout the stage. The simplest is Category 4, which is usually less than 2 kilometers long. The most difficult climbs are referred to as “Hors Catégorie,” or “beyond categorization.” A climb is sometimes given this designation because of its vertical elevation rise or because it ends at the top.

How do professional female cyclists pee during a race?

Because many women’s races are under 5 hours, we normally pee 8 times right before the race and can hold it until the end if necessary. Other times, a rider will stop to potty and then get in the car to assist them in getting back. At least not on purpose, no woman pees herself while riding!

Can anyone ride the Tour de France?

Although the event is primarily for amateurs, it is available to anybody who is 18 years or older on race day. (Younger riders may enter with permission from their parents.) It is marketed to ‘amateurs,’ yet it also attracts potential and former professionals. It’s been ridden by Greg LeMond, Raymond Poulidor, and Miguel Induráin.

How fast do they go downhill in Tour de France?

To say the obvious, Tour de France riders are in excellent physical condition. They’re nearly twice as fit as the average non-Tour rider of the same age group who’s in fair to good form, according to the gold standard of cardiovascular fitness, V02 max (or how much oxygen your body can utilize per minute).

How fast do cyclist go in Tour de France?

The champion of the tour has averaged roughly 25 miles per hour (40 kilometers per hour) over the last few years–but that is throughout the entire tour. Everything is averaged at 25 mph, including uphill, downhill, time trial, and flatland. Weirdly, they’re a little speedier than we are. Quite a bit.

How much weight do Tour de France riders lose?

Van der Stelt explains that in the event of an emergency, the maximum weight loss would be 0.5kg. Though calorie burn and consumption vary by person, she claims the riders consume up to 8,000 calories a day – “taking on 10% extra every day, just in case,” she says, which can lead to weight gain.

What do Tour de France riders eat during race?

Riders may eat carbohydrate snacks such as bananas or protein bars while travelling. They’ll refuel with a mix of homemade rice cakes and tailored items like snacks and gels during the race.

What is Autobus?

Every stage of the Tour de France has a time limit, and on mountainous days, the autobus forms as non-climbers from all teams fight together to finish within the cut-off. The grupetto is another name for it.

What is Bidon?

A bidon is an abandoned water bottle, and many roadside fans will try to gather them as mementoes.

What is Breakaway?

During a stage, a small group of riders (or an individual) surge away from the main bunch.

What is bunch spirit?

Flatter stages usually end in a bunch sprint, which is a high-octane, hell-for-leather contest for stage honours between the peloton’s fastest sprinters.

Despite the fact that the race comes at the finish line in a group sprint, the stage win is decided by the sprinters and their lead-out riders.

What is Combativity award?

According to the race commissaires, this prize is given to the most aggressive rider each day.

The combativity award honors the rider who enlivened the stage by forming a breakaway, attacking frequently, or staying out in front of the pack for an extended period of time. The winner can be easily spotted the next day thanks to their red race numbers. At the conclusion of the race, an overall combativity medal is granted.

What is Feed zone?

Lunchtime. Every stage has its own feed zone, when riders slow down to collect musettes (small bags containing food and drinks) from their team soigneurs.

What is Flamme rouge?

A red air bridge marks the one-kilometer mark, beneath which a red kite flies.

What is General Classification?

After each stage, the riders’ finishing times are tallied. The riders are sorted by their total time, plus or minus any bonuses or penalties, in the general classification. The famed yellow jersey is worn by the cyclist who has completed the race in the least amount of time.

What is Grand Départ?

The ‘Big Beginning.’ Riders will begin the Grand Départ in Copenhagen this year 2022.

What is Grand Tour?

The Tour de France, Giro d’Italia, and Vuelta a Espana are cycling’s three most prestigious stage events, each lasting three weeks.

What is Intermediate sprint?

Each stage has an intermediate sprint with points and prize money for the first riders across it, in addition to the finish line.

What is King of the Mountains?

The mountains classification, one of the Tour de France’s secondary prizes, ranks the first riders over each of the race’s classified climbs. The more difficult the climb, the more points are available for that climb. The King of the Mountains, who wears the polka-dot jersey, is the leader in the mountains classification.

What is Lanterne rouge?

The lanterne rouge is the final rider on the general classification, named after the red light attached on the back of a train.

What is Maillot jaune/yellow jersey?

The general classification leader wears the distinctive yellow jersey, or maillot jaune. Last year, the yellow jersey was won by Tadej Pogaar (UAE Team Emirates).

What is Maillot vert/green jersey?

The leader in the points classification is awarded the green shirt. Peter Sagan has won the sprinters’ classification seven times, owing to the fact that more points are available on flatter stages.

What is Maillot a pois/polka-dot jersey?

The leader of the mountains classification is awarded this characteristic white jersey with red polka-dots.

What is Maillot blanc/white jersey?

The highest-placed young rider in the general classification wears the white jersey. This year’s youth classification is open to any riders born on or after January 1, 1996.

What is Musette?

A tiny cloth shoulder bag containing a rider’s food and extra bidons that is distributed in the feed zone.

What is Parcours?

The race’s ‘course,’ or the route it will take.

What is Points classification?

Points are awarded to the top finishers in each stage and intermediate sprint, based on their position. These points are combined together to generate a points classification, with the green jersey worn by the leader.

What is Team time trial?

This year, there will be no team time trial. The time of a team is determined when the fifth rider crosses the finish line.

What is Time trial?

Individual time trials will be held on stages 5 and 20 of this year’s Tour de France, totalling 58 kilometres between them – the most kilometres against the clock since 2013.

Riders set off on specialised time trial bikes in reverse general classification order with the goal of finishing the stage in the shortest time.

Individual time trials, termed the “race of truth,” can cause significant shifts in overall classification. A time trial will be held on the Tour’s penultimate stage, as it was last year, and it might determine who wears the yellow jersey on the final day and rides into Paris as the victor.

What is a Rouleur?

A rouleur is an all-rounder and often one of the hardest riders in the peloton, capable of excelling on a variety of terrains and making a superb domestique.

What is a Soigneur?

The soigneur is the unsung hero of a team’s backroom staff, in charge of looking after cyclists off the bike and handing out musettes, bidons, and extra layers of clothing during the race.

What is Sprinter?

On the flatter stages, sprinters battle it out with their peloton counterparts, capable of remarkable bursts of acceleration over short distances.

What is a Sprint Train?

Before a group sprint, sprint trains form, with teammates offering a wheel for their sprinter to follow through the pandemonium.

The lead-out guy will be at the rear of the train, with the team’s sprinter on his wheel, ready to dash for the finish as soon as possible.

What is a Team Classification?

The team classification system assigns a score to each team based on the total time of their top three finishers on each stage. Yellow helmets are sometimes worn by team classification leaders to help them stand out in the peloton.

If you have any suggestions or advise, please feel free to reach us via our Contact Us here.

DIY Research

If you are a research nerd and interested in publishing research papers or articles, we highly recommend that treat Google as your best friend or contact us.

2022 Tour de France: How Time Has Evolved The Tour

2022 tour de france: list of participating teams, understanding the 2022 tour de france: a comprehensive guide, 2022 mountain bike | trek 820 | review, buying a new bicycle there are 11 things you should consider, 2022 tour de france: jerseys and their meanings, tour de france: all winners since beginning 1903, tour de france: interesting historical facts, what you need to know about tour de france, the origins of the tour de france.

Tour de France bikes: Who's riding what in 2021

A roundup of the bikes you will see at this year's Tour de France

The Tour de France is widely accepted as the most prestigious bike race in the world. The bikes in use at the Tour de France are up there with the very best that money can buy.

All of the bikes used in the 2021 Tour de France are made from carbon fibre. That includes their frames, wheels and most of the components such as handlebars and seatposts.

Tadej Pogacar (UAE Team Emirates) won the 2020 Tour de France riding a Colnago - for the Italian brand's first-ever Tour win, no less - but there are plenty of other manufacturers in the race. In terms of bike frames, there are 19 different brands in the 2021 race, with three different manufacturers of groupsets and 15 different wheel brands. Each of these brands is continually innovating and improving in a bid to improve their products and outdo their competitors. To do this, they look at the various barriers that a rider needs to overcome in order to go faster. Aerodynamics is a big focus, but rolling resistance, friction and of course weight are key areas of attention.

Tour de France bike weight

Cycling's governing body, the UCI (Union Cycliste Internationale), has long imposed a minimum weight limit of 6.8kg for the bikes in any of its sanctioned races - the Tour de France included.

It was first introduced in the year 2000 to ensure manufacturers didn't cut corners on safety in a race for the lightest bike possible, and while the weight limit has been contested many times in the years since, the UCI has remained steadfast.

In terms of the rule book, there is no upper limit on the weight of a Tour de France bike, but of course the lighter a bike is, the faster it will be when the gradient of the road starts to rise. All else being equal, a lighter bike will also accelerate more quickly and be easier to handle, so teams will do everything they can to get their bikes down to this 6.8kg limit, usually allowing 100 grams or so, to account for the discrepancy between their scales and the UCI's.

The introduction of disc brakes on road bikes made this a tougher task, since the disc braking system is heavier overall, and the introduction of aerodynamic tube shapes has also yielded heavier frames, but even so, the weight of most bikes in the peloton will hover between 6.8kg and around 7.2kg. Some of the heaviest bikes will push closer to 8kg, but these will be aero bikes and will typically only be used on the flatter days, where weight is less of an issue.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Moreover, time trial bikes, with their deep tube shapes, rear disc wheels and deep section front wheels will weigh even more again. It's not uncommon for a time trial bike in the Tour de France to weigh in the region of 8-9kg, with the heavier time trial bikes nudging closer to 10kg.

As a result of this minimum weight limit, manufacturers are no longer racing to make the lightest bike possible, and brands have instead focussed on the other areas for innovation. The result is a host of ongoing debates that continually simmer away, such as the rim vs disc brakes debate, the inner tube vs tubeless tyres debate, and more.

Disc brakes vs rim brakes

The first of these debates doesn't centre around technology that speeds you up, but tech that slows you down: brakes.

Disc brakes have been popular in mountain biking for well over a decade and over the past few years finally made their way onto the road. As of the start of this season, all but one of the major teams is using disc brakes. Most teams and their bike sponsors are wholly committed to the technology, while a few teams still have rim brake bikes in their fleet.

Ineos Grenadiers are the sole representatives of #savetherimbrake and their talents continue to prove that the now out of favour technology is far from futile, but the fact remains that disc brakes are taking over.

Many riders have an opinion on the matter, and former Ineos leader Chris Froome has made his point clear , but it's likely only a matter of time before the whole peloton is stopping with discs, perhaps as soon as next season.

Tubular vs tubeless vs clincher

Tyre technology came into the mainstream during last year's delayed Tour de France, when Specialized sponsored teams Deceuninck-QuickStep and Bora Hansgrohe took to the roads with a surprising choice of clincher tyres fitted with inner tubes inside.

For years, tubular tyres have been the favoured son in the peloton because they feature tyres that are glued to the rim. That means when they puncture, the tyre stays on the rim and allows a rider to continue until it is safe (or tactically preferable) to stop for a wheel or bike change.

Over recent years, tubeless tyres have been gaining popularity, since they promise to automatically repair any punctures, meaning that a rider doesn't need to stop at all. However, in the grass roots of cycling, from amateur racers to cycle commuters, the humble inner tube has reigned supreme for decades.

With the improvement in tyre technology, rim design and the interface between the two, as well as the performance of tyres when fitted with latex inner tubes, the choice of clincher tyres was deemed the fastest option by Deceuninck-QuickStep and their wheel sponsors Roval.

As for which technology will be most widely adopted in this year's race, only time will tell.

New bikes at the Tour de France

The Tour de France is the biggest bike race in the world and so is a global veritable shop window for cycling brands and team sponsors. Racing also makes for a thorough testbed for the durability of new tech and is often used by brands to test out prototypes prior to launch.

Here at Cyclingnews , we'll be keeping our beady eyes on the race to seek out any of these prototypes and share what we find.

New Dura-Ace

One such new piece of technology that has already broken cover is the new Dura-Ace groupset from Shimano. Expected to be known as Dura-Ace R9200, the groupset was spotted on the bikes of Team DSM's riders at the Baloise Belgium Tour and is expected to be more widely adopted at the Tour de France.

With the aforementioned shop window effect of the Tour de France, the biggest new tech releases we tend to spot at any edition of the race are new bikes. Last year, two brands (Factor and Canyon) used the race to test out their respective impending bike launches, and we expect it to be no different this year.

After a recent sighting, the most widely anticipated is a new Pinarello Dogma , expected to be ridden by Pinarello-sponsored Ineos Grenadiers, but there are new bikes aplenty in the time trial scene, with a new Factor Slick spotted at the end of the Giro d'Italia and a new Trek Speed Concept used at the Critérium du Dauphiné.

In addition to the bikes, the summer so far has been a hotbed for new wheel launches. Almost all top-tier wheel brands have announced new wheels already, so we'll be keeping an eye on the rolling stock of teams' bikes to ensure nothing passes us by.

AG2R Citröen Team

Road bikes: BMC Teammachine SLR01

Time trial bikes: BMC Warp TT

Groupset: Campagnolo Super Record EPS

Wheels: Campagnolo

Clothing: Rosti

Saddles: Fizik

Finishing Kit: BMC

Computers: Wahoo

Alpecin-Fenix

Road bikes: Canyon Aeroad, Canyon Ultimate

Time trial bikes: Canyon Speedmax

Groupset: Shimano Dura-Ace Di2 Disc

Wheels: Shimano (Aerocoach & Princeton Carbonworks are non-sponsor additions)

Clothing: Kalas Sportswear

Saddles: Fizik

Finishing Kit: Canyon

Computers: Wahoo

Astana-Premier Tech

Road bikes: Wilier Zero SLR, Wilier Filante

Time trial bikes: Wilier Turbine TT

Wheels: Corima

Clothing: Giordana

Saddles: Prologo

Finishing Kit: Wilier

Computers: Garmin

B&B Hotels p/b KTM

Road bikes: KTM Revelator Lisse, KTM Revelator Alto

Time trial bikes: KTM Solus

Wheels: DT Swiss

Clothing: Gobik

Finishing Kit: FSA

Computers: Bryton

Bahrain Victorious

Road bikes: Merida Reacto, Merida Scultura

Time trial bikes: Merida Warp TT

Wheels: Vision

Clothing: Ale

Finishing Kit: FSA, Vision, Prologo

Bora-Hansgrohe

Road bikes: Specialized S-Works Tarmac SL7

Time trial bikes: Specialized S-Works Shiv

Wheels: Roval

Clothing: Sportful

Saddles: Specialized

Finishing Kit: PRO, Specialized

Road bikes: De Rosa Merak, De Rosa Pininfarina SK

Time trial bikes: De Rosa TT-03

Groupset: Campagnolo Super Record EPS

Wheels: Fulcrum

Clothing: Nalini

Saddles: Selle Italia

Finishing Kit: Errea

Deceuninck-QuickStep

Road bikes: Specialized S-Works Tarmac SL7, Specialized Aethos

Clothing: Vermarc

EF Education-Nippo

Road bikes: Cannondale SuperSix Evo, Cannondale SystemSix

Time trial bikes: Cannondale SuperSlice

Wheels: Vision

Clothing: Rapha

Finishing Kit: FSA, Vision

Groupama-FDJ

Road bikes: Lapierre Aircode DRS, Lapierre Xelius SL

Time trial bikes: Lapierre Aerostorm DRS

Wheels: Shimano

Finishing Kit: PRO

Ineos Grenadiers

Road bikes: Pinarello Dogma F12 rim

Time trial bikes: Pinarello Bolide TT

Groupset: Shimano Dura-Ace Di2 rim

Wheels: Shimano (Lightweight, Princeton Carbonworks & Aerocoach are non-sponsored additions)

Clothing: Castelli

Finishing Kit: MOST

Intermarché-Wanty Gobert

Road bikes: Cube Litening C:68X

Time trial bikes: Cube Aerium C:68 TT

Wheels: Newmen

Clothing: Santic, NoPinz

Finishing Kit: Cube

Israel Start-Up Nation

Road bikes: Factor OSTRO V.A.M

Time trial bikes: Factor Slick

Wheels: Black Inc, (Lightweight is a non-sponsor addition)

Clothing: Jinga

Saddles: Selle Italie

Finishing Kit: Black Inc

Computers: Hammerhead

Jumbo–Visma

Road bikes: Cervelo R5, Cervelo S5, Cervelo Caledonia

Time trial bikes: Cervelo P5

Groupset: Shimano Dura-Ace Di2

Wheels: Shimano (Vision & Aerocoach are non-sponsor additions)

Clothing: Agu

Lotto Soudal

Road bikes: Ridley Helium, Ridley Noah Fast

Time trial bikes: Ridley Dean TT

Groupset: Campagnolo Super Record EPS, C-Bear ceramic bearings

Wheels: Campagnolo

Finishing Kit: Deda

Movistar Team

Road bikes: Canyon Ultimate, Canyon Aeroad

Time trial bikes: Canyon Speedmax

Groupset: SRAM Red eTap AXS

Wheels: Zipp

Qhubeka Assos

Road bikes: BMC Teammachine SLR, BMC Timemachine Road

Time trial bikes: BMC Timemachine

Groupset: Shimano Dura-Ace Di2 Disc, Rotor crankset

Wheels: Hunt

Clothing: Assos

Finishing Kit: BMC

Arkéa Samsic

Clothing: Craft

Team BikeExchange

Road bikes: Bianchi Specialissima, Bianchi Oltre XR4

Time trial bikes: Bianchi Aquila TT

Wheels: Shimano, Vision

Road bikes: Scott Addict RC, Scott Foil RC

Time trial bikes: Scott Plasma

Clothing: Team's own (Keep Challenging)

Saddles: PRO

Finishing Kit: Syncros

Total Direct Energie

Road bikes: Wilier Cento10Air, Wilier Zero SLR

Time trial bikes: Wilier Turbine

Wheels: Ursus

Trek–Segafredo

Road bikes: Trek Madone, Trek Emonda

Time trial bikes: Trek Speed Concept

Wheels: Bontrager

Clothing: Santini

Saddles: Bontrager

Finishing Kit: Bontrager

UAE Team Emirates

Road bikes: Colnago V3Rs, Colnago Concept, Colnago C64

Time trial bikes: Colnago K-One

Computers: SRM

Thank you for reading 5 articles in the past 30 days*

Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read any 5 articles for free in each 30-day period, this automatically resets

After your trial you will be billed £4.99 $7.99 €5.99 per month, cancel anytime. Or sign up for one year for just £49 $79 €59

Try your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

As the Tech Editor here at Cyclingnews, Josh leads on content relating to all-things tech, including bikes, kit and components in order to cover product launches and curate our world-class buying guides, reviews and deals. Alongside this, his love for WorldTour racing and eagle eyes mean he's often breaking tech stories from the pro peloton too.

On the bike, 32-year-old Josh has been riding and racing since his early teens. He started out racing cross country when 26-inch wheels and triple chainsets were still mainstream, but he found favour in road racing in his early 20s and has never looked back. He's always training for the next big event and is keen to get his hands on the newest tech to help. He enjoys a good long ride on road or gravel, but he's most alive when he's elbow-to-elbow in a local criterium.

Florian Sénéchal blames sponsor Bianchi after four bike swaps at Paris-Roubaix

Tech trends from Paris-Roubaix: Nine things we learned

Paris-Roubaix jury report: Visma-Lease a Bike's top finisher Tim van Dijke relegated

Most Popular

By Fabian Cancellara April 05, 2024

By Will Jones April 05, 2024

By Tim Maloney April 05, 2024

By Tom Wieckowski April 04, 2024

By Laura Weislo April 04, 2024

By Stephen Farrand April 04, 2024

By Alasdair Fotheringham April 03, 2024

By Will Jones April 03, 2024

By Josh Ross April 02, 2024

By Laura Weislo April 01, 2024

By Fabian Cancellara April 01, 2024

Subscribe to my YouTube channel for video reviews.

How Much Does a Tour de France Bike Weigh in 2023?

KEY TAKEAWAY

The average Tour de France bike weight was 7.2 kg in 2020 , 7.1 kg in 2021 , 7.1 kg in 2022 , and 7.08 kg in 2023 .

I gathered the weights of all road bikes used by all cycling teams (World Tour + Pro Continental) on the Tour de France since 2020 and did the math. It surprised me that only a few bikes weigh 6.8 kg, which is the UCI limit. Many bikes exceed 7 kg, especially the aero ones.

Anyway, let’s scrutinize the bikes in more depth.

Abbreviations used: PT – Pro Tour Team, WT – World Tour Team, UCI – Union Cycliste Internationale

A Few Words About This Research

When searching for the weights of the TdF road bikes, I faced multiple challenges:

- The bike weights vary depending on the bike size, specifications, and components.

- Not all weights were available (e.g., on the manufacturers’ websites, in magazines, or online).

- Most of the bike weights are based on factory specifications. TdF bikes often have different specifications, so the final weight varies. The problem is getting to the actual bikes and comparing the same sizes. In addition, the specs can vary from stage to stage.

Based on these notes, it is clear that the weights are rather indicative, and the real weights may vary by an estimated ±200g.

Tour de France Bike Weight in 2023

The following table shows the bikes of all teams participating in the 2023 Tour de France.

The average 2023 Tour de France bike weight is 7.08 kg .

The average 2023 Tour de France aero bike weight is 7.19 kg .

The average 2023 Tour de France lightweight bike weight is 6.96 kg .

Tour de France Bike Weight in 2022

The following table shows the bikes of all teams participating in the 2022 Tour de France.

The average 2022 Tour de France bike weight is 7.1 kg .

The average 2022 Tour de France aero bike weight is 7.25 kg .

The average 2022 Tour de France lightweight bike weight is 6.93 kg .

Check out these weight statistics of road bikes . I summarized over 400 bikes and categorized them to determine how the brake and frame type influence the overall weight.

Tour de France Bike Weight in 2021

The following table shows the bikes of all teams participating in the 2021 Tour de France.

The average 2021 Tour de France bike weight was 7.1 kg .

The average 2021 Tour de France aero bike weight was 7.27 kg .

The average 2021 Tour de France lightweight bike weight was 6.97 kg .

See the Tour de France bikes prices .

Tour de France Bike Weight in 2020

The following table shows the bikes of all teams participating in the 2020 Tour de France.

The average 2020 Tour de France bike weight was 7.22 kg .

The average 2020 Tour de France aero bike weight was 7.41 kg .

The average weight of a lightweight 2020 Tour de France bike was 7.03 kg .

You might also be interested in these Tour de France statistics that include info about riders’ weights, heights, BMI, and more.

The weight of Tour de France bikes fluctuates between 6.8 kg (the minimum weight stated by the UCI regulations) and 7.5 kg . However, some bikes can exceed this weight.

Aero road bikes, for example, are about 300g heavier on average than lightweight (or all-rounder) road bikes.

The same applies to disc brake road bikes. In 2021, most teams used disc brakes (which are heavier than rim brakes), except for teams like INEOS-Grenadiers or UAE. In 2023, no team used rim brakes.

Do you think the UCI will update the weight limit in the future so that bikes weighing 6.5 kg or even less will be allowed?

If you find any mistakes, don’t hesitate to contact me. Thank you!

Tour de France Bikes FAQ

UCI introduced the minimum weight limit already in 2000. Its main purpose is to protect cyclists against failures (and subsequent crashes) caused by too-light bike frame parts. If a crucial part is poorly designed and there is not enough material to make it stiff and durable, the risk of failure is higher.

No, there is no upper weight limit for a TdF bike.

The preview picture ©A.S.O./Charly Lopez (cropped)

Browse Other Cycling Statistics

General Stats Bicycle Statistics & Facts Best Bicycle Brands Road Bike Prices & Weights Statistics Road Bike Wheels Weights Statistics How Much Does a Tour de France Bike Cost?

Grand Tours Cycling Grand Tours Statistics (Compared) Tour de France Statistics Giro d’Italia Statistics Vuelta a España Statistics

Cycling Monuments Cycling Monuments (Compared) Milan–San Remo Statistics Tour of Flanders Statistics Paris–Roubaix Statistics Liège-Bastogne-Liège Statistics Giro di Lombardia Statistics

Browse Road Bikes

Road Bikes for Beginners Endurance Road Bikes

Road Bikes Under $1,000 Road Bikes Under $2,000 Road Bikes Under $3,000 Road Bikes Under $5,000 Road Bikes Over $10,000

Chinese Carbon Road Bikes

About The Author

Petr Minarik

2 thoughts on “how much does a tour de france bike weigh in 2023”.

Hello Petr, Thanks for your post which is really interesting and informative. I am writing a paper about composite materials used in Tour de France. I am wondering where you found these bike weights. Thank you!

Hi Yi, Thanks! I used manufacturer’s websites as the primary source. Then magazine and comparison websites, eventually videos. – Petr

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Start typing and press enter to search

Tour de France: How many calories will the winner burn?

Professor of Physics, University of Lynchburg

Disclosure statement

John Eric Goff does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

Imagine you begin pedaling from the start of Stage 17 of this year’s Tour de France . First, you would bike approximately 70 miles (112 km) with a gradual increase in elevation of around 1,300 feet (400 m). But you’ve yet to hit the fun part: the Hautes-Pyrénées mountains. Over the next 40 miles (64 km) you would have to climb three mountain peaks with a net increase of a mile (1.6 km) in elevation . On the fittest day of my life, I might not even be able to finish Stage 17 – much less do it in anything remotely close to the five hours or so the winner will take to finish the ride. And Stage 17 is just one of 21 stages that must be completed in the 23 days of the tour.

I am a sports physicist , and I’ve modeled the Tour de France for nearly two decades using terrain data – like what I described for Stage 17 – and the laws of physics. But I still cannot fathom the physical capabilities needed to complete the world’s most famous bike race. Only an elite few humans are capable of completing a Tour de France stage in a time that’s measured in hours instead of days. The reason they’re able to do what the rest of us can only dream of is that these athletes can produce enormous amounts of power. Power is the rate at which cyclists burn energy and the energy they burn comes from the food they eat. And over the course of the Tour de France, the winning cyclist will burn the equivalent of roughly 210 Big Macs.

Cycling is a game of watts

To make a bicycle move, a Tour de France rider transfers energy from his muscles, through the bicycle and to the wheels that push back on the ground. The faster a rider can put out energy, the greater the power. This rate of energy transfer is often measured in watts. Tour de France cyclists are capable of generating enormous amounts of power for incredibly long periods of time compared to most people.

For about 20 minutes, a fit recreational cyclist can consistently put out 250 watts to 300 watts . Tour de France cyclists can produce over 400 watts for the same time period . These pros are even capable of hitting 1,000 watts for short bursts of time on a steep uphill – roughly enough power to run a microwave oven .

But not all of the energy a Tour de France cyclist puts into his bike gets turned into forward motion. Cyclists battle air resistance and frictional losses between their wheels and the road. They get help from gravity on downhills but they have to fight gravity while climbing.

I incorporate all of the physics associated with cyclist power output as well as the effects of gravity, air resistance and friction into my model . Using all that, I estimate that a typical Tour de France winner needs to put out an average of about 325 watts over the roughly 80 hours of the race. Recall that most recreational cyclists would be happy if they could produce 300 watts for just 20 minutes!

Turning food into miles

So where do these cyclists get all this energy from? Food, of course!

But your muscles, like any machine, can’t convert 100% of food energy directly into energy output – muscles can be anywhere between 2% efficient when used for activities like swimming and 40% efficient in the heart . In my model, I use an average efficiency of 20%. Knowing this efficiency as well as the energy output needed to win the Tour de France, I can then estimate how much food the winning cyclist needs.

Top Tour de France cyclists who complete all 21 stages burn about 120,000 calories during the race – or an average of nearly 6,000 calories per stage. On some of the more difficult mountain stages – like this year’s Stage 17 – racers will burn close to 8,000 calories. To make up for these huge energy losses, riders eat delectable treats such as jam rolls, energy bars and mouthwatering “jels” so they don’t waste energy chewing .

Last year’s winner , Tadej Pogačar, weighs only 146 pounds. Tour de France cyclists don’t have much fat to burn for energy. They have to keep putting food energy into their bodies so they can put out energy at what seems like a superhuman rate. So this year, while watching a stage of the Tour de France, note how many times the cyclists eat – now you know the reason for all that snacking.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter .]

- Tour de France

- Pyrenees mountains

- Significant Figures

- Sports medicine

Senior Research Development Coordinator

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

Here's How This Team Fuels Its Riders for the Most Grueling Race in the World

Nutrient-packed meals and snacks galore keep EF Pro Cycling Riders rolling strong.

And it’s not like they have any weight to lose. They’re already riding the razor’s edge between top performance and tanking immunity, so keeping them well fed and fully nourished is of the utmost importance.

In that regard, the team chefs are the real stars of the show, says Nigel Mitchell, R.D., head of nutrition for EF Pro Cycling .

“We are able to maintain an energy balance with the riders over a grand tour. We can get the energy back in them that they’re burning. And that’s because the chefs help provide them with good food, fueling strategies, and plenty of opportunities to eat,” Mitchell says.

But it wasn’t always this way. “Fifteen or so years ago, it was harder. The riders spoke a lot about flavor or food fatigue—being tired of eating! That’s because they didn’t have team chefs,” Mitchell says. “They ate at hotels that had the same menu every day—chicken and pasta, chicken and pasta over and over. They got tired of it. The food was also calorie dense, but nutrient light, so the riders didn’t feel great after eating. Today, the chefs pack the foods with nutrition and flavor. We never hear about food fatigue these days,” he says.

Here’s a look at what goes into making those perfect menus, meals, and feeding opportunities.

Begin the Day Right With Breakfast

Four hours before go time, the riders stream into the café for a morning meal, which consists of omelets, toast, jams and nut butters, and oatmeal with an array of toppings like seeds and nuts, Mitchell says. “They have a chance to really fuel up for the day right away.”

Get on the Snacking Bus

After breakfast, the riders get packed up and get on the bus to the start. “The bus is a real performance center,” Mitchell says. “The soigneurs make race foods like paninis and rice cakes. Those are on the bus along with bananas and energy bars, and of course, coffees. There’s plenty of snacking to be done on the bus.”

Stuff Those Pockets

The riders are eating about 400 to 500 calories an hour on the bike in the form of gels, bars, drinks, and food, Mitchell says. “Before they go to the start, they’re stocking their pockets with their favorite race foods. We make sure there’s a good variety of flavors and foods. And of course they’ll be plenty of chances to grab more snacks in the feed zones and from the race car out on course.”

Maximize the Macros

With the focus on real food, it’s relatively easy to make sure the riders get all the macronutrients—fat, protein, and carbs—they need, Mitchell says. The carbs are pretty straight forward, since they’re munching them morning through night. The team pays closer attention to protein, making sure riders get a minimum of 2 grams of protein per kg of body weight, so 140 grams for a 70 kg (~150 lb.) rider.

“We make sure they have protein at every meal, so it’s well spaced throughout the day as they need it,” Mitchell says. “With two or three eggs and oatmeal with toppings, it’s easy to get 30 or 40 grams right away at breakfast. There’s a little protein in their race foods, like the paninis. Then they get a recovery shake with 20 grams when they’re done and plenty of protein with dinner and evening snacks.”

“Fat is under appreciated and extremely important for health, immunity, and performance,” Mitchell says. To make sure the riders get enough, EF provides omega-3 supplements as well as snacks that contain healthy fats, including seeds and nuts like pistachios, which contain alpha-linoleic acid (ALA), which converts to the omega-3 eicosapentenoic acid (EPA) in the body to help fight inflammation and preserve muscle tissue.

Hydration matters. Like food, the team management makes sure there’s plenty of water and other hydration beverages at every turn for their riders. “We get a body weight and take a urine sample from the riders each morning,” Mitchell says. “That’s very crude science, but it gives us an idea of their hydration status. I’ve done 30 grand tours, and I have never had a rider with serious hydration issues the morning of a race.”

Riders can choose the drink mix flavors they prefer. EF also uses Skratch Superfuel , a high carb drink that contains a carbohydrate called cluster dextrin, which digests steadily like real food and doesn’t get in the way of your hydration like some dense, high-calorie drinks can. “We can get 300 or 400 calories in one bottle, which is really quite incredible,” Mitchell says.

Recover Right

The riders get their recovery drinks straight away after the finish. Then onto the bus for more snacking until they get to their destination where dinner awaits. “Dinner is typically a lean white meat, a couple sources of carbs, vegetables, salad and dessert,” Mitchell says. “There’s also a food room back at the hotel, so they can grab some snacks like dried fruit and nuts before bed.”

Real juice from vegetables is a great performance and health enhancer during an arduous three-week grand tour, Mitchell says. “As the tour wears on, the riders really feel like they need extra nutrition, but they literally can’t eat enough vegetables and salad without feeling like all the fiber is just sitting in their stomach,” Mitchell says.

“So we remove some of the fiber by juicing the vegetables. That way they can pack in all the nutrients from carrots and beets and other vegetables without having to eat it all. They still have salad, but they don’t feel like they need to try to eat as much of it. I introduced vegetable juicing at Team Sky 10 years ago and now everyone does it.”

Go with Gut-Friendly Foods

Your gut flora is essential for proper digestion and good health and performance and it takes a beating during a grand tour with all the heavy exertion and incredibly high calorie load, Mitchell says. “We work to protect gut flora and health as best we can because if it becomes compromised so does your digestion. I remember talking to a rider in the late 1990s and early 2000s who said he would just lie in bed with his stomach distended by the end of the Tour because his gut health was so compromised.”

To avoid that, Mitchell focuses on foods that are more alkaline than acidic. “Lots of sports drinks and foods are acidic. We’re looking to lower that load. So, for instance, you can have one gel, no problem. If you take eight during a race, that could be a problem. That’s where real foods like rice cakes and bananas are so important. They help maintain a healthy pH in the gut, so it can do its job releasing digestive enzymes and breaking down food and absorbing nutrients.”

Food for a Happy Mood

Finally, everyone knows that food is more than fuel. It’s also comfort and even a source of joy. When you’re pushing your pedals for more than two thousand miles over monstrous mountain passes through all types of weather, trying to stay upright and avoid massive crashes and chaos, you need all the joy you can get. That’s why the team makes sure the riders get some special meals.

“Once or twice a week we try to have steaks,” Mitchell says. “Usually before flat stages or the day before a rest day, so they have plenty of time for digestion. It’s good for the riders nutritionally, of course. But from an emotional point of view, it’s really important.”

Likewise the last supper on the night before the last stage, the table is set with happy mood foods, Mitchell says. “The chef will ask what they want and inevitably, it’s homemade burgers and fries. That’s really good mood food. It makes them happy as well as go fast.”

.css-1t6om3g:before{width:1.75rem;height:1.75rem;margin:0 0.625rem -0.125rem 0;content:'';display:inline-block;-webkit-background-size:1.25rem;background-size:1.25rem;background-color:#F8D811;color:#000;background-repeat:no-repeat;-webkit-background-position:center;background-position:center;}.loaded .css-1t6om3g:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/bicycling/static/images/chevron-design-element.c42d609.svg);} Tour de France

Challengers of the 2024 Giro d'Italia and TdF

2024 Tour de France May Start Using Drones

The 2024 Tour de France Can’t Miss Stages

Riders Weigh In on the Tour de France Routes

2024 Tour de France Femmes Can't-Miss Stages

How Much Money Do Top Tour de France Teams Make?

2024 Tour de France/ Tour de France Femmes Routes

How Much Did Tour de France Femmes Riders Earn?

5 Takeaways from the Tour de France Femmes

Who Won the 2023 Tour de France Femmes?

Results From the 2023 Tour de France Femmes

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

Cycling Road

Understanding the Increase in Weight of Tour de France Bikes

The UCI, cycling’s international governing body, has a rule stating that bikes must weigh no less than 6.8kg to prevent teams and bike manufacturers from building bikes that are too light and fragile to withstand the rigors of professional racing.

There were once times when pro cycling teams mocked the rule as being outdated because, with our current technology, bike manufacturers can easily make carbon fiber bikes that weigh far less than 6.8kg while still meeting the EN ISO 4210-6 safety requirements.

In fact, pro teams used to artificially add extra weight to their bikes to meet the 6.8kg weight limit rule.

However, new generations of Tour de France bikes are now significantly heavier than they used to be. The average bike in the pro peloton today weighs around 7.2kg. Why?

In this article, we’ll discuss why road bikes are getting heavier and why that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

What Is The Average Tour de France Bike Weight?

Based on videos of GCN and CyclingTips who regularly weigh Tour de France bikes every year, aero bikes weigh upwards of 7.5kg. But most importantly, bikes that the Tour de France pros use in mountainous stages weigh from 7.0 to 7.3kg. This is far above the UCI weight limit of 6.8kg.

Looking back to 2015 and earlier, lightweight bikes are so much lighter. Trek Emonda , for example, which first launched in 2014 and weighs 4.6kg was the lightest production bike at the time. Then there are the first and second versions of Cannondale SuperSix Evo Hi-Mod that weigh less than 6.8kg even without the highest-level components.

Of course, you can’t race them in UCI-sanctioned races, but these bikes were the norm. Even if you can’t race with them, everyone can buy these bikes.

Clearly, manufacturers know how to actually make lightweight bikes that are safe to use. At one time, they just decided not to.

Despite today’s weight inflation, though, apparently, Tour de France riders are getting faster than ever. So, what happened there? Why are lightweight bikes getting heavier and why are these new-gen heavy bikes faster than the old lightweight ones?

The Advantage of Aerodynamics

Because carbon fiber technology advanced so quickly and bikes were getting so light, the UCI did have a second look at their 6.8kg regulations a few years ago. Ultimately, they decided to keep the rule in place.

Because of that, pro teams artificially added extra weights to their bikes. This is often in the form of heavier components or leads taped to the frame or wheels. This brings the bike up to the minimum weight limit.

Later, companies realize that instead of adding dead weights, which gives pros no advantage during the race, they might as well add weights that do make them faster.

With the help of wind tunnel testing, bike companies have been able to design bikes that are more aerodynamic than ever before. Other than the thicker frame tubes, features such as integrated handlebars and stems, hidden cables, and deep-section wheels, all of this help reduce drag and make the bike faster.

Because of all these features, aero bikes are significantly heavier than lightweight bikes. And this is the first reason why we’re seeing the start of inflation in Tour de France bike weights.

The Rise of All-Arounder Bikes

But aero bikes aren’t new. For a while, pros have been switching between lightweight bikes for mountainous stages and aero bikes for flat/sprint stages.

They thought because aero bikes are heavier, they wouldn’t be able to climb as well as lightweight bikes. But as it turns out, that’s not always the case. As long as pros are able to ride above 30km/h, aero properties will always be more important than weight. Even on the longest and steepest mountain like the Alps the Huez, grand tour riders can still hold an average speed of 20km/h where some aerodynamic properties still matter.

So there’s a sweet spot between weight and aero, which gives birth to all-arounder bikes. They are essentially climbing bikes with some aero optimization, giving them a little bit of extra weight but can climb faster than pure climbing bikes on most hills because of the aero shapes.

The Specialized Tarmac is one example of an all-arounder bike. It’s not the lightest in the market, but with some aero features, it’s one of the fastest bikes you can buy.

Optimized for aero and equipped with deeper-section carbon wheels, most of these lightweight all-around bikes weigh from 6.8 to 7.5kg.

The Age of Disc Brakes

The final reason for the current state of Tour de France bikes is the rise of disc brakes. Disc brake bikes are heavier than their rim brake counterparts, but most top-level aero and all-arounder bikes come equipped with disc brakes now.

Not only the calipers and disc rotors themselves are heavier, but the fork, frame seat stay, chain stay, and wheels of a disc brake-compatible bike must also be reinforced and be made heavier than their rim brake counterparts to compensate for the higher stopping force.

All combined, a top-level disc brake road bike is said to weigh about 500g more than a rim brake bike of the same model.

But all these weights are not for nothing. Sure, rim brakes vs disc brakes preference is still a very controversial topic even today, but there are some clear advantages of disc brakes that make almost all pro teams ride exclusively disc brakes today.

With disc brakes, you can slow down from a high speed with better reliability, and as a result, pros are more confident in going on a higher-speed descent. Disc brakes also have better compatibility with tubeless tire setup, which has a lower rolling resistance compared to standard butyl or tubular setup.

The use of disc brakes also allows wider rims and tires, which can lower rolling resistance and add comfort. These will surely add weight, but looking at how pro peloton has been continuously increasing their tire width from 23mm to 28mm today, the swap must’ve been worth it.

Is Disc Brake the Biggest Contributor to Weight Inflation?

Aero and disc brakes are surely the main contributors to why Tour de France bikes are now heavier than 6.8kg. The disc brake has been blamed as the reason why bikes today are so much heavier than older rim brake bikes. But is that true?

To answer that, we need to look at road bike manufacturers who still give a choice to customers whether they want a rim brake or disc brake bike.

The best example of this is the Pinarello Dogma F since it’s one of the new-gen bikes that still have a rim brake option.

In a video on the YouTuber GC Performance’s channel, he weighed the Dogma F rim brake bike in size 53 with a Campagnolo Super Record EPS groupset and Princeton 4540 wheels with White Industries hubs. The total weight without pedals is 7.19kg.

In another of his video , he weighed the disc brake version of Pinarello Dogma F. Same paint job, same size, same groupset, but heavier wheels (Princeton 4550, slightly deeper than the 4550). The weight? Also 7.19kg.

What happened there? Why is the rim brake bike not lighter than the disc brake variation?