What Is on Voyager’s Golden Record?

From a whale song to a kiss, the time capsule sent into space in 1977 had some interesting contents

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino

Senior Editor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Voyager-records-631.jpg)

“I thought it was a brilliant idea from the beginning,” says Timothy Ferris. Produce a phonograph record containing the sounds and images of humankind and fling it out into the solar system.

By the 1970s, astronomers Carl Sagan and Frank Drake already had some experience with sending messages out into space. They had created two gold-anodized aluminum plaques that were affixed to the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecraft. Linda Salzman Sagan, an artist and Carl’s wife, etched an illustration onto them of a nude man and woman with an indication of the time and location of our civilization.

The “Golden Record” would be an upgrade to Pioneer’s plaques. Mounted on Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, twin probes launched in 1977, the two copies of the record would serve as time capsules and transmit much more information about life on Earth should extraterrestrials find it.

NASA approved the idea. So then it became a question of what should be on the record. What are humanity’s greatest hits? Curating the record’s contents was a gargantuan task, and one that fell to a team including the Sagans, Drake, author Ann Druyan, artist Jon Lomberg and Ferris, an esteemed science writer who was a friend of Sagan’s and a contributing editor to Rolling Stone .

The exercise, says Ferris, involved a considerable number of presuppositions about what aliens want to know about us and how they might interpret our selections. “I found myself increasingly playing the role of extraterrestrial,” recounts Lomberg in Murmurs of Earth , a 1978 book on the making of the record. When considering photographs to include, the panel was careful to try to eliminate those that could be misconstrued. Though war is a reality of human existence, images of it might send an aggressive message when the record was intended as a friendly gesture. The team veered from politics and religion in its efforts to be as inclusive as possible given a limited amount of space.

Over the course of ten months, a solid outline emerged. The Golden Record consists of 115 analog-encoded photographs, greetings in 55 languages, a 12-minute montage of sounds on Earth and 90 minutes of music. As producer of the record, Ferris was involved in each of its sections in some way. But his largest role was in selecting the musical tracks. “There are a thousand worthy pieces of music in the world for every one that is on the record,” says Ferris. I imagine the same could be said for the photographs and snippets of sounds.

The following is a selection of items on the record:

Silhouette of a Male and a Pregnant Female

The team felt it was important to convey information about human anatomy and culled diagrams from the 1978 edition of The World Book Encyclopedia. To explain reproduction, NASA approved a drawing of the human sex organs and images chronicling conception to birth. Photographer Wayne F. Miller’s famous photograph of his son’s birth, featured in Edward Steichen’s 1955 “Family of Man” exhibition, was used to depict childbirth. But as Lomberg notes in Murmurs of Earth , NASA vetoed a nude photograph of “a man and a pregnant woman quite unerotically holding hands.” The Golden Record experts and NASA struck a compromise that was less compromising— silhouettes of the two figures and the fetus positioned within the woman’s womb.

DNA Structure

At the risk of providing extraterrestrials, whose genetic material might well also be stored in DNA, with information they already knew, the experts mapped out DNA’s complex structure in a series of illustrations.

Demonstration of Eating, Licking and Drinking

When producers had trouble locating a specific image in picture libraries maintained by the National Geographic Society, the United Nations, NASA and Sports Illustrated , they composed their own. To show a mouth’s functions, for instance, they staged an odd but informative photograph of a woman licking an ice-cream cone, a man taking a bite out of a sandwich and a man drinking water cascading from a jug.

Olympic Sprinters

Images were selected for the record based not on aesthetics but on the amount of information they conveyed and the clarity with which they did so. It might seem strange, given the constraints on space, that a photograph of Olympic sprinters racing on a track made the cut. But the photograph shows various races of humans, the musculature of the human leg and a form of both competition and entertainment.

Photographs of huts, houses and cityscapes give an overview of the types of buildings seen on Earth. The Taj Mahal was chosen as an example of the more impressive architecture. The majestic mausoleum prevailed over cathedrals, Mayan pyramids and other structures in part because Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan built it in honor of his late wife, Mumtaz Mahal, and not a god.

Golden Gate Bridge

Three-quarters of the record was devoted to music, so visual art was less of a priority. A couple of photographs by the legendary landscape photographer Ansel Adams were selected, however, for the details captured within their frames. One, of the Golden Gate Bridge from nearby Baker Beach, was thought to clearly show how a suspension bridge connected two pieces of land separated by water. The hum of an automobile was included in the record’s sound montage, but the producers were not able to overlay the sounds and images.

A Page from a Book

An excerpt from a book would give extraterrestrials a glimpse of our written language, but deciding on a book and then a single page within that book was a massive task. For inspiration, Lomberg perused rare books, including a first-folio Shakespeare, an elaborate edition of Chaucer from the Renaissance and a centuries-old copy of Euclid’s Elements (on geometry), at the Cornell University Library. Ultimately, he took MIT astrophysicist Philip Morrison’s suggestion: a page from Sir Isaac Newton’s System of the World , where the means of launching an object into orbit is described for the very first time.

Greeting from Nick Sagan

To keep with the spirit of the project, says Ferris, the wordings of the 55 greetings were left up to the speakers of the languages. In Burmese , the message was a simple, “Are you well?” In Indonesian , it was, “Good night ladies and gentlemen. Goodbye and see you next time.” A woman speaking the Chinese dialect of Amoy uttered a welcoming, “Friends of space, how are you all? Have you eaten yet? Come visit us if you have time.” It is interesting to note that the final greeting, in English , came from then-6-year-old Nick Sagan, son of Carl and Linda Salzman Sagan. He said, “Hello from the children of planet Earth.”

Whale Greeting

Biologist Roger Payne provided a whale song (“the most beautiful whale greeting,” he said, and “the one that should last forever”) captured with hydrophones off the coast of Bermuda in 1970. Thinking that perhaps the whale song might make more sense to aliens than to humans, Ferris wanted to include more than a slice and so mixed some of the song behind the greetings in different languages. “That strikes some people as hilarious, but from a bandwidth standpoint, it worked quite well,” says Ferris. “It doesn’t interfere with the greetings, and if you are interested in the whale song, you can extract it.”

Reportedly, the trickiest sound to record was a kiss . Some were too quiet, others too loud, and at least one was too disingenuous for the team’s liking. Music producer Jimmy Iovine kissed his arm. In the end, the kiss that landed on the record was actually one that Ferris planted on Ann Druyan’s cheek.

Druyan had the idea to record a person’s brain waves, so that should extraterrestrials millions of years into the future have the technology, they could decode the individual’s thoughts. She was the guinea pig. In an hour-long session hooked to an EEG at New York University Medical Center, Druyan meditated on a series of prepared thoughts. In Murmurs of Earth , she admits that “a couple of irrepressible facts of my own life” slipped in. She and Carl Sagan had gotten engaged just days before, so a love story may very well be documented in her neurological signs. Compressed into a minute-long segment, the brain waves sound, writes Druyan, like a “string of exploding firecrackers.”

Georgian Chorus—“Tchakrulo”

The team discovered a beautiful recording of “Tchakrulo” by Radio Moscow and wanted to include it, particularly since Georgians are often credited with introducing polyphony, or music with two or more independent melodies, to the Western world. But before the team members signed off on the tune, they had the lyrics translated. “It was an old song, and for all we knew could have celebrated bear-baiting,” wrote Ferris in Murmurs of Earth . Sandro Baratheli, a Georgian speaker from Queens, came to the rescue. The word “tchakrulo” can mean either “bound up” or “hard” and “tough,” and the song’s narrative is about a peasant protest against a landowner.

Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode”

According to Ferris, Carl Sagan had to warm up to the idea of including Chuck Berry’s 1958 hit “Johnny B. Goode” on the record, but once he did, he defended it against others’ objections. Folklorist Alan Lomax was against it, arguing that rock music was adolescent. “And Carl’s brilliant response was, ‘There are a lot of adolescents on the planet,’” recalls Ferris.

On April 22, 1978, Saturday Night Live spoofed the Golden Record in a skit called “Next Week in Review.” Host Steve Martin played a psychic named Cocuwa, who predicted that Time magazine would reveal, on the following week’s cover, a four-word message from aliens. He held up a mock cover, which read, “Send More Chuck Berry.”

More than four decades later, Ferris has no regrets about what the team did or did not include on the record. “It means a lot to have had your hand in something that is going to last a billion years,” he says. “I recommend it to everybody. It is a healthy way of looking at the world.”

According to the writer, NASA approached him about producing another record but he declined. “I think we did a good job once, and it is better to let someone else take a shot,” he says.

So, what would you put on a record if one were being sent into space today?

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino | | READ MORE

Megan Gambino is a senior web editor for Smithsonian magazine.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Voyager Golden Record Was Made

By Timothy Ferris

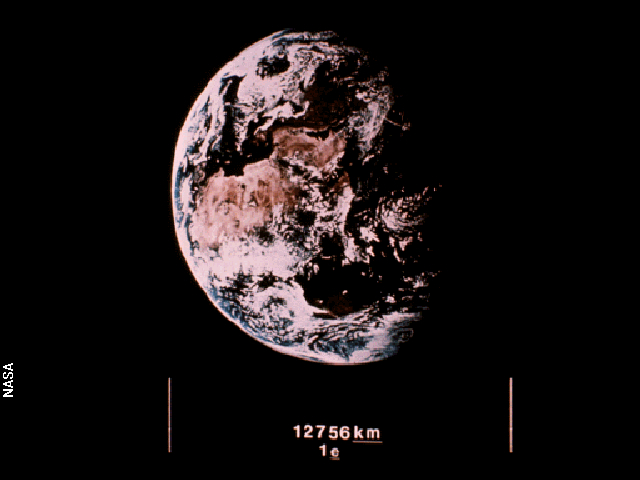

We inhabit a small planet orbiting a medium-sized star about two-thirds of the way out from the center of the Milky Way galaxy—around where Track 2 on an LP record might begin. In cosmic terms, we are tiny: were the galaxy the size of a typical LP, the sun and all its planets would fit inside an atom’s width. Yet there is something in us so expansive that, four decades ago, we made a time capsule full of music and photographs from Earth and flung it out into the universe. Indeed, we made two of them.

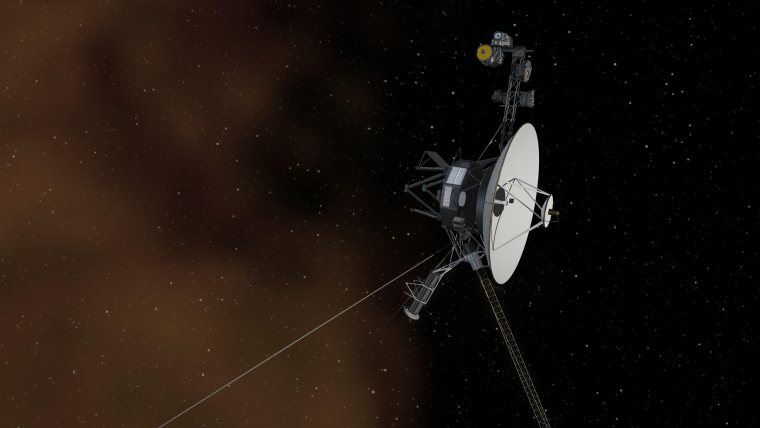

The time capsules, really a pair of phonograph records, were launched aboard the twin Voyager space probes in August and September of 1977. The craft spent thirteen years reconnoitering the sun’s outer planets, beaming back valuable data and images of incomparable beauty . In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first human-made object to leave the solar system, sailing through the doldrums where the stream of charged particles from our sun stalls against those of interstellar space. Today, the probes are so distant that their radio signals, travelling at the speed of light, take more than fifteen hours to reach Earth. They arrive with a strength of under a millionth of a billionth of a watt, so weak that the three dish antennas of the Deep Space Network’s interplanetary tracking system (in California, Spain, and Australia) had to be enlarged to stay in touch with them.

If you perched on Voyager 1 now—which would be possible, if uncomfortable; the spidery craft is about the size and mass of a subcompact car—you’d have no sense of motion. The brightest star in sight would be our sun, a glowing point of light below Orion’s foot, with Earth a dim blue dot lost in its glare. Remain patiently onboard for millions of years, and you’d notice that the positions of a few relatively nearby stars were slowly changing, but that would be about it. You’d find, in short, that you were not so much flying to the stars as swimming among them.

The Voyagers’ scientific mission will end when their plutonium-238 thermoelectric power generators fail, around the year 2030. After that, the two craft will drift endlessly among the stars of our galaxy—unless someone or something encounters them someday. With this prospect in mind, each was fitted with a copy of what has come to be called the Golden Record. Etched in copper, plated with gold, and sealed in aluminum cases, the records are expected to remain intelligible for more than a billion years, making them the longest-lasting objects ever crafted by human hands. We don’t know enough about extraterrestrial life, if it even exists, to state with any confidence whether the records will ever be found. They were a gift, proffered without hope of return.

I became friends with Carl Sagan, the astronomer who oversaw the creation of the Golden Record, in 1972. He’d sometimes stop by my place in New York, a high-ceilinged West Side apartment perched up amid Norway maples like a tree house, and we’d listen to records. Lots of great music was being released in those days, and there was something fascinating about LP technology itself. A diamond danced along the undulations of a groove, vibrating an attached crystal, which generated a flow of electricity that was amplified and sent to the speakers. At no point in this process was it possible to say with assurance just how much information the record contained or how accurately a given stereo had translated it. The open-endedness of the medium seemed akin to the process of scientific exploration: there was always more to learn.

In the winter of 1976, Carl was visiting with me and my fiancée at the time, Ann Druyan, and asked whether we’d help him create a plaque or something of the sort for Voyager. We immediately agreed. Soon, he and one of his colleagues at Cornell, Frank Drake, had decided on a record. By the time NASA approved the idea, we had less than six months to put it together, so we had to move fast. Ann began gathering material for a sonic description of Earth’s history. Linda Salzman Sagan, Carl’s wife at the time, went to work recording samples of human voices speaking in many different languages. The space artist Jon Lomberg rounded up photographs, a method having been found to encode them into the record’s grooves. I produced the record, which meant overseeing the technical side of things. We all worked on selecting the music.

I sought to recruit John Lennon, of the Beatles, for the project, but tax considerations obliged him to leave the country. Lennon did help us, though, in two ways. First, he recommended that we use his engineer, Jimmy Iovine, who brought energy and expertise to the studio. (Jimmy later became famous as a rock and hip-hop producer and record-company executive.) Second, Lennon’s trick of etching little messages into the blank spaces between the takeout grooves at the ends of his records inspired me to do the same on Voyager. I wrote a dedication: “To the makers of music—all worlds, all times.”

To our surprise, those nine words created a problem at NASA . An agency compliance officer, charged with making sure each of the probes’ sixty-five thousand parts were up to spec, reported that while everything else checked out—the records’ size, weight, composition, and magnetic properties—there was nothing in the blueprints about an inscription. The records were rejected, and NASA prepared to substitute blank discs in their place. Only after Carl appealed to the NASA administrator, arguing that the inscription would be the sole example of human handwriting aboard, did we get a waiver permitting the records to fly.

In those days, we had to obtain physical copies of every recording we hoped to listen to or include. This wasn’t such a challenge for, say, mainstream American music, but we aimed to cast a wide net, incorporating selections from places as disparate as Australia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, China, Congo, Japan, the Navajo Nation, Peru, and the Solomon Islands. Ann found an LP containing the Indian raga “Jaat Kahan Ho” in a carton under a card table in the back of an appliance store. At one point, the folklorist Alan Lomax pulled a Russian recording, said to be the sole copy of “Chakrulo” in North America, from a stack of lacquer demos and sailed it across the room to me like a Frisbee. We’d comb through all this music individually, then meet and go over our nominees in long discussions stretching into the night. It was exhausting, involving, utterly delightful work.

“Bhairavi: Jaat Kahan Ho,” by Kesarbai Kerkar

In selecting Western classical music, we sacrificed a measure of diversity to include three compositions by J. S. Bach and two by Ludwig van Beethoven. To understand why we did this, imagine that the record were being studied by extraterrestrials who lacked what we would call hearing, or whose hearing operated in a different frequency range than ours, or who hadn’t any musical tradition at all. Even they could learn from the music by applying mathematics, which really does seem to be the universal language that music is sometimes said to be. They’d look for symmetries—repetitions, inversions, mirror images, and other self-similarities—within or between compositions. We sought to facilitate the process by proffering Bach, whose works are full of symmetry, and Beethoven, who championed Bach’s music and borrowed from it.

I’m often asked whether we quarrelled over the selections. We didn’t, really; it was all quite civil. With a world full of music to choose from, there was little reason to protest if one wonderful track was replaced by another wonderful track. I recall championing Blind Willie Johnson’s “Dark Was the Night,” which, if memory serves, everyone liked from the outset. Ann stumped for Chuck Berry’s “ Johnny B. Goode ,” a somewhat harder sell, in that Carl, at first listening, called it “awful.” But Carl soon came around on that one, going so far as to politely remind Lomax, who derided Berry’s music as “adolescent,” that Earth is home to many adolescents. Rumors to the contrary, we did not strive to include the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun,” only to be disappointed when we couldn’t clear the rights. It’s not the Beatles’ strongest work, and the witticism of the title, if charming in the short run, seemed unlikely to remain funny for a billion years.

“Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground,” by Blind Willie Johnson

Ann’s sequence of natural sounds was organized chronologically, as an audio history of our planet, and compressed logarithmically so that the human story wouldn’t be limited to a little beep at the end. We mixed it on a thirty-two-track analog tape recorder the size of a steamer trunk, a process so involved that Jimmy jokingly accused me of being “one of those guys who has to use every piece of equipment in the studio.” With computerized boards still in the offing, the sequence’s dozens of tracks had to be mixed manually. Four of us huddled over the board like battlefield surgeons, struggling to keep our arms from getting tangled as we rode the faders by hand and got it done on the fly.

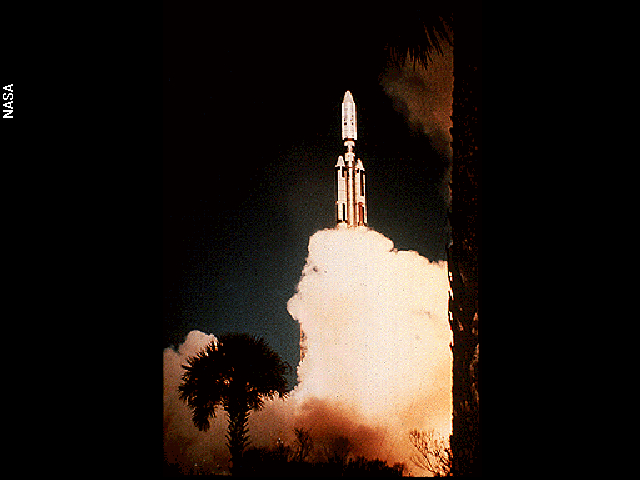

The sequence begins with an audio realization of the “music of the spheres,” in which the constantly changing orbital velocities of Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, and Jupiter are translated into sound, using equations derived by the astronomer Johannes Kepler in the sixteenth century. We then hear the volcanoes, earthquakes, thunderstorms, and bubbling mud of the early Earth. Wind, rain, and surf announce the advent of oceans, followed by living creatures—crickets, frogs, birds, chimpanzees, wolves—and the footsteps, heartbeats, and laughter of early humans. Sounds of fire, speech, tools, and the calls of wild dogs mark important steps in our species’ advancement, and Morse code announces the dawn of modern communications. (The message being transmitted is Ad astra per aspera , “To the stars through hard work.”) A brief sequence on modes of transportation runs from ships to jet airplanes to the launch of a Saturn V rocket. The final sounds begin with a kiss, then a mother and child, then an EEG recording of (Ann’s) brainwaves, and, finally, a pulsar—a rapidly spinning neutron star giving off radio noise—in a tip of the hat to the pulsar map etched into the records’ protective cases.

“The Sounds of Earth”

Ann had obtained beautiful recordings of whale songs, made with trailing hydrophones by the biologist Roger Payne, which didn’t fit into our rather anthropocentric sounds sequence. We also had a collection of loquacious greetings from United Nations representatives, edited down and cross-faded to make them more listenable. Rather than pass up the whales, I mixed them in with the diplomats. I’ll leave it to the extraterrestrials to decide which species they prefer.

“United Nations Greetings/Whale Songs”

Those of us who were involved in making the Golden Record assumed that it would soon be commercially released, but that didn’t happen. Carl repeatedly tried to get labels interested in the project, only to run afoul of what he termed, in a letter to me dated September 6, 1990, “internecine warfare in the record industry.” As a result, nobody heard the thing properly for nearly four decades. (Much of what was heard, on Internet snippets and in a short-lived commercial CD release made in 1992 without my participation, came from a set of analog tape dubs that I’d distributed to our team as keepsakes.) Then, in 2016, a former student of mine, David Pescovitz, and one of his colleagues, Tim Daly, approached me about putting together a reissue. They secured funding on Kickstarter , raising more than a million dollars in less than a month, and by that December we were back in the studio, ready to press play on the master tape for the first time since 1977.

Pescovitz and Daly took the trouble to contact artists who were represented on the record and send them what amounted to letters of authenticity—something we never had time to accomplish with the original project. (We disbanded soon after I delivered the metal master to Los Angeles, making ours a proud example of a federal project that evaporated once its mission was accomplished.) They also identified and corrected errors and omissions in the information that was provided to us by recordists and record companies. Track 3, for instance, which was listed by Lomax as “Senegal Percussion,” turns out instead to have been recorded in Benin and titled “Cengunmé”; and Track 24, the Navajo night chant, now carries the performers’ names. Forty years after launch, the Golden Record is finally being made available here on Earth. Were Carl alive today—he died in 1996 at the age of sixty-two—I think he’d be delighted.

This essay was adapted from the liner notes for the new edition of the Voyager Golden Record, recently released as a vinyl boxed set by Ozma Records .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Anthony Lydgate

By Megan Amram

By Manvir Singh

Voyager's Special Cargo: The Golden Record

This image highlights the special cargo onboard NASA's Voyager spacecraft: the Golden Record. Each of the two Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977 carry a 12-inch gold-plated phonograph record with images and sounds from Earth. An artist's rendering of the Voyager spacecraft is shown at bottom right, with a yellow circle denoting the location of the Golden Record. The cover of the Golden Record, shown on upper right, carries directions explaining how to play the record, a diagram showing the location of our sun and the two lowest states of the hydrogen atom as a fundamental clock reference. The larger image to the left is a magnified picture of the record inside.

The Voyagers were built by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., which continues to operate both spacecraft. JPL is a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. The Voyager missions are a part of the NASA Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate.

For more information about the Voyager spacecraft, visit http://www.nasa.gov/voyager and http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov .

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66094266/82_EatingLickingDrinking_HermanEckelmann_NAIC.0.0.0.0.jpg)

Filed under:

The 116 photos NASA picked to explain our world to aliens

Share this story.

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: The 116 photos NASA picked to explain our world to aliens

If any intelligent life in our galaxy intercepts the Voyager spacecraft, if they evolved the sense of vision, and if they can decode the instructions provided, these 116 images are all they will know about our species and our planet, which by then could be long gone:

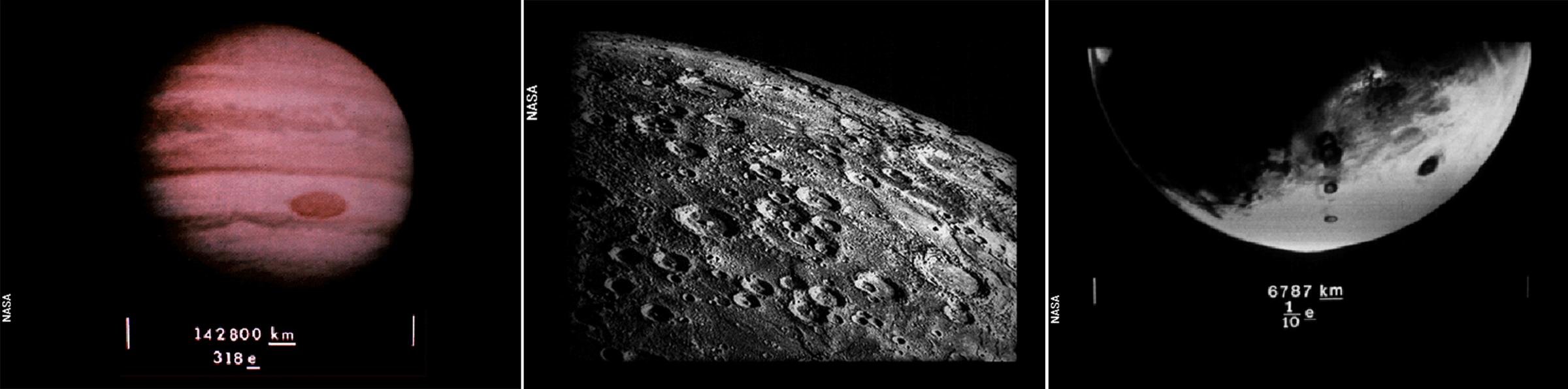

When Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 launched into space in 1977, their mission was to explore the outer solar system, and over the following decade, they did so admirably.

With an 8-track tape memory system and onboard computers that are thousands of times weaker than the phone in your pocket, the two spacecraft sent back an immense amount of imagery and information about the four gas giants, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

But NASA knew that after the planetary tour was complete, the Voyagers would remain on a trajectory toward interstellar space, having gained enough velocity from Jupiter's gravity to eventually escape the grasp of the sun. Since they will orbit the Milky Way for the foreseeable future, the Voyagers should carry a message from their maker, NASA scientists decided.

The Voyager team tapped famous astronomer and science popularizer Carl Sagan to compose that message. Sagan's committee chose a copper phonograph LP as their medium, and over the course of six weeks they produced the "Golden Record": a collection of sounds and images that will probably outlast all human artifacts on Earth.

How would aliens know what to do with the Golden Record?

The records are mounted on the outside of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 and protected by an aluminum case. Etched on the cover of that case are symbols explaining how to decode the record. Put yourself in an extraterrestrial's shoes and try to guess what the etchings seek to communicate. Stumped? Hover over or click on the yellow circles for the intended meaning of these interstellar brain teasers:

What else is on the Golden Record?

Any aliens who come across the Golden Record are in for a treat. It contains:

- 116 images encoded in analog form depicting scientific knowledge, human anatomy, human endeavors, and the terrestrial environment. (These images appear in color in the video above, but on the record, all but 20 are black and white.)

- Spoken greetings in more than 50 languages.

- A compilation of sounds from Earth.

- Nearly 90 minutes of music from around the world. Notably missing are the Beatles, who reportedly wanted to contribute "Here Comes the Sun" but couldn't secure permission from their record company. For the video above, I chose to include "Dark Was the Night" by Blind Willie Johnson, a 1927 track Sagan described as "haunting and expressive of a kind of cosmic loneliness."

The committee also made space for a message from the president of the United States:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/4249653/carter.0.jpg)

Where are they now?

Incredibly, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are still communicating with Earth — they aren't expected to lose power until the 2020s. That's how NASA knew that Voyager 1 became the first ever spacecraft to enter interstellar space in 2012: The probe detected high-density plasma characteristic of the space beyond the heliosphere (the bubble of solar wind created by the sun).

Voyager 2 is currently traveling through the outer layers of the heliosphere. It's moving southward relative to Earth's orbit, while Voyager 1 is moving northward. In more than 40,000 years, they will each pass closer to another star than they are to our sun. (Or, more accurately, stars will pass by them).

There are three other spacecraft headed toward interstellar space; two of them, Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11, are shown in this somewhat dated illustration:

NASA launched Pioneer 10 and 11 in 1972 and 1973, and has since lost communication with both. They aren't traveling as fast as the Voyagers, but they will eventually enter interstellar space as well.

They too, carry a message for extraterrestrial life, in the form of a 6-by-9-inch gold-anodized aluminum plaque, designed by Sagan and other members of the team that would go on to create the Voyager Golden Record five years later.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/4252067/GPN-2000-001621-x.0.jpg)

Like the Golden Record, the plaque features the pulsar map, uses hydrogen to define the binary units, and depicts humankind. NASA faced a backlash for the nudity of the human figures.

Another interstellar message

The fifth probe that will exit our solar system is New Horizons , the spacecraft that flew by Pluto in 2015. It is headed in a broadly similar direction as Voyager 2, but having launched in 2006, it's many years behind. It may not reach interstellar space for another 30 years.

New Horizons was sent into space without any message like the Golden Record, but it's not too late to add one. A group led by Jon Lomberg , a member of Sagan's Golden Record team, is trying to convince NASA to upload a crowdsourced message to the probe for any intelligent life that might come across it.

The spacecraft's memory system is similar to a flash drive, and it wouldn't be as durable as the copper records on Voyager. "The most conservative estimates are a lifetime of a few decades. Other physicists and engineers believe the message might remain for centuries or even millennia," says the website of the message initiative, adding, more hopefully, "Another unknown is the advanced technology possessed by any ETs who find the spacecraft. They might have ways of reading the faded memory we cannot yet imagine."

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

You need $500. How should you get it?

The lies that sell fast fashion, streaming got expensive. now what, sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Voyager Golden Record Finally Finds An Earthly Audience

Alexi Horowitz-Ghazi

The Voyager Golden Record remained mostly unavailable and unheard, until a Kickstarter campaign finally brought the sounds to human ears. Ozma Records/LADdesign hide caption

The Voyager Golden Record remained mostly unavailable and unheard, until a Kickstarter campaign finally brought the sounds to human ears.

The Golden Record is basically a 90-minute interstellar mixtape — a message of goodwill from the people of Earth to any extraterrestrial passersby who might stumble upon one of the two Voyager spaceships at some point over the next couple billion years.

But since it was made 40 years ago, the sounds etched into those golden grooves have gone mostly unheard, by alien audiences or those closer to home.

"The Voyager records are the farthest flung objects that humans have ever created," says Timothy Ferris, a veteran science and music journalist and the producer of the Golden Record. "And they're likely to be the longest lasting, at least in the 20th century."

In the late 1970s, Ferris was recruited by his friend, astronomer Carl Sagan, to join a team of scientists, artists and engineers to help create two engraved golden records to accompany NASA's Voyager mission — which would eventually send a pair of human spacecraft beyond the outer rings of the solar system for the first time in history.

Carl Sagan And Ann Druyan's Ultimate Mix Tape

Ferris was tasked with the technical aspects of getting the various media onto the physical LP, and with helping to select the music. In addition to greetings in dozens of languages and messages from leading statesmen, the records also contained a sonic history of planet Earth and photographs encoded into the record's grooves. But mostly, it was music.

"We were gathering a representation of the music of the entire earth," Ferris says. "That's an incredible wealth of great stuff."

Ferris and his colleagues worked together to sift through Earth's enormous discography to decide which pieces of sound would best represent our planet. They really only had two criteria: "One was: Let's cast a wide net. Let's try to get music from all over the planet," he says. "And secondly: Let's make a good record."

That meant late nights of listening sessions while "almost physically drowning in records," Ferris says.

The final selection, which was engraved in copper and plated in gold, included opera, rock 'n' roll, blues, classical music and field recordings selected by ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax .

When Voyager 1 and its identical sister craft Voyager 2 launched in 1977, each carried a gold record titled T he Sounds Of Earth that contained a selection of recordings of life and culture on Earth. The cover contains instructions for any extraterrestrial being wishing to play the record. NASA/Getty Images hide caption

When Voyager 1 and its identical sister craft Voyager 2 launched in 1977, each carried a gold record titled T he Sounds Of Earth that contained a selection of recordings of life and culture on Earth. The cover contains instructions for any extraterrestrial being wishing to play the record.

Ferris says that from the very start, many people on the production team expected and hoped for the record to be commercially released soon after the launch of Voyager.

"Carl Sagan tried to interest labels in releasing Voyager," Ferris says. "It never worked."

Ferris says that's likely because the music rights were owned by several different record labels who were hesitant to share the bill. So — except for a limited CD-ROM release in the early 1990s — the record went largely unheard by the wider world.

David Pescovitz, an editor at technology news website Boing Boing and a research director at the nonprofit Institute for the Future, was seven years old when the Voyager spacecraft launched.

"When you're seven years old and you hear that a group of people created a phonograph record as a message for possible extraterrestrials and launched it on a grand tour of the solar system," says Pescovitz, "it sparks the imagination."

A couple years ago, Pescovitz and his friend Tim Daly, a record store manager at Amoeba Music in San Francisco, decided to collaborate on bringing the Golden Record to an earthbound audience.

Pescovitz approached his former graduate school professor — none other than Ferris, the Golden Record's original producer — about the project, and Ferris gave his blessing, with one important caveat.

Voyagers' Records Wait for Alien Ears

"You can't release a record without remastering it," says Ferris. "And you can't remaster without locating the master."

That turned out to be a taller order than expected. The original records were mastered in a CBS studio, which was later acquired by Sony — and the master tapes had descended into Sony's vaults.

Pescovitz enlisted the company's help in searching for the master tapes; in the meantime, he and Daly got to work acquiring the rights for the music and photographs that comprised the original. They also reached out to surviving musicians whose work had been featured on the record to update incomplete track information.

Finally, Pescovitz and Daly got word that one of Sony's archivists had found the master tapes.

Pescovitz remembers the moment he, Daly and Ferris traveled to Sony's Battery Studios in New York City to hear the tapes for the first time.

"They hit play, and the sounds of the Solomon Islands pan pipes and Bach and Chuck Berry and the blues washed over us," Pescovitz says. "It was a very moving and sublime experience."

Daly says that, in remastering the album, the team decided not to clean up the analog artifacts that had made their way onto the original master tapes, in order to preserve the record's authenticity down to its imperfections.

"We wanted it to be a true representation of what went up," Daly says.

Pescovitz and Daly teamed up with Lawrence Azerrad, a graphic designer who has made record packaging for the likes of Sting and Wilco , to design a luxuriant box set, complete with a coffee table book of photographs and, of course, tinted vinyl.

"I mean, if you do a golden record box set, you have to do it on gold vinyl," Daly says.

They put the project on Kickstarter and expected to sell it mostly to vinyl collectors, space nerds and audiophiles — but they underestimated the appeal.

"The internet was just on fire, talking about this thing," Daly says.

They blew past their initial funding goal in two days, eventually raising more than $1.3 million dollars, making it the most successful musical Kickstarter campaign ever. Among the initial 11,000 contributors were family members of NASA's original Voyager mission team.

An Alien View Of Earth

Last week, Ferris got his box set in the mail. He says that his friend, the late Carl Sagan, would be delighted by what they made.

"I think this record exceeds Carl's — not only his expectations, but probably his highest hopes for a release of the Voyager record," Ferris says. "I'm glad these folks were finally able to make it happen."

Pescovitz says he's just glad to have returned the Golden Record to the world that created it.

At a moment of political division and media oversaturation, Pescovitz and Daly say they hope that their Golden Record can offer a chance for people to slow down for a moment; to gather around the turntable and bask in the crackly sounds of what Sagan called the "pale blue dot" that we call home.

"As much as it was a gift from humanity to the cosmos, it was really a gift to humanity as well," Pescovitz says. "It's a reminder of what we can accomplish when we're at our best."

Here’s What Humanity Wanted Aliens to Know About Us in 1977

I t was nearly 30 years ago—Jan. 24, 1986, nearly a decade after it had been launched—that the Voyager 2 spacecraft made its closest pass to Uranus and, as TIME phrased it, “taught scientists more about Uranus than they had learned in the entire 205 years since it was discovered.”

But the sophisticated equipment that sent information back to NASA wasn’t the only important thing on board the spacecraft. The Voyager 2, like the Voyager 1, carried with it a record, plated in gold, on which had been encoded sounds and images meant to “portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth,” according to NASA . The message from Earth was curated by a committee led by Carl Sagan and contained 115 images of “scenes from Earth.”

It was estimated in 1977, when the Voyagers launched, that it would take 40,000 years for them to reach a star system where there might be a being capable of deciphering the record. But, should that ever happen, what exactly could those photos say about humanity? Here’s a hint, from a few of the pictures on the golden record, and our best guesses at how hypothetical aliens might interpret them:

Cute young Earthlings and an image of their planet, or maybe giant Earthlings and a smaller planet under their control:

A fully grown earthling, or maybe a demonstration of the kinds of weapons available on earth:.

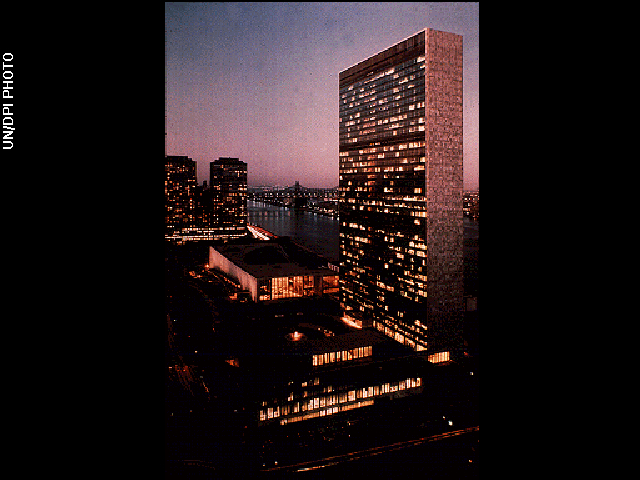

An Earth city building at sunset, or maybe the spacecraft with which a large number of Earthlings will come find you:

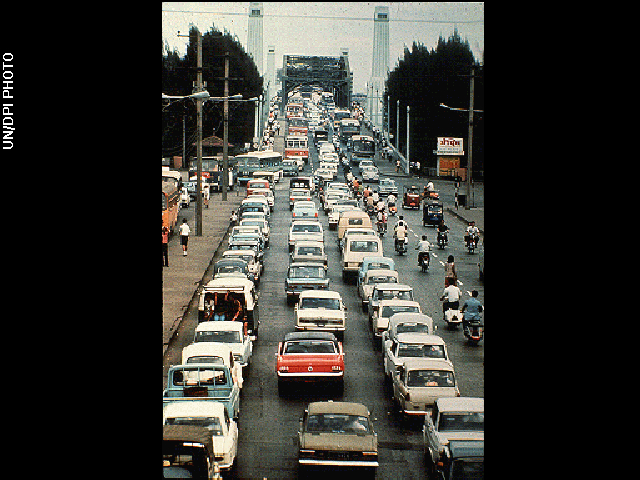

Earth traffic jam, or maybe why Earthlings will be fleeing to move to your home planet:

Earth scientist at work, or maybe an Earthling with goggles that can see you right now:

How this thing got to you, or maybe a missile:

An image of early Earth spaceflight, or a being we abandoned in space:

Celestial bodies near the Earth, Jupiter, Mercury and Mars, or maybe the places we’ve already conquered:

Where to find us, or maybe where to stay away from:

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Hear NASA’s ‘Golden Record’ From 1977 Voyager Mission

By Ryan Reed

In 1977, NASA launched the two Voyager spacecrafts with gold-plated records featuring sound collages showcasing the diverse culture, nature and industry of planet Earth – from Chuck Berry to Bach, industrial machinery to volcanic eruptions. The “Golden Record” project, led by author-astrophysicist Carl Sagan, was an optimistic attempt to communicate with extra-terrestrial life – or anyone else who may stumble upon the discs (and figure out how to play them).

Nearly 40 years later, the records – hand-etched with the greeting, “To the makers of music – all worlds, all times” – are still drifting in their search for interstellar contact. But BBC Radio 3 has compiled some of these disparate sounds into an hour-long digital playlist, available to stream at their website .

The mix begins with an introduction from 1977 UN Secretary General Kurt Waldheim. “As the Secretary General of the United Nations, an organization of 147 member states who represent almost all of the human inhabitants of the planet Earth, I send greetings on behalf of the people of our planet,” he says. “We step out of our solar system into the universe seeking only peace and friendship – to teach if we are called upon, to be taught if we are fortunate. We know full well that our planet and all its inhabitants are but a small part of this immense universe that surrounds us, and it is with humility and hope that we take this step.”

Trump’s Team Has a Plan to Ensure He Doesn’t Go to Jail for Violating Gag Order

Kendrick did everything he needed to on ‘euphoria’, ted cruz wants airlines to keep your cash when they cancel your flight, billie eilish would like to reintroduce herself.

Also included are human greetings in 55 different languages, with a blend of music and field recordings spanning all corners of the Earth, including blues pioneer Blind Willie Johnson, composer Igor Stravinsky, Australian aboriginal songs and the hum of planes and trains.

Along with the sprawling audio, Voyager housed 118 photographs and, according to a NASA report , the “brain waves of a young women [sic] in love.” The “Golden Record” project team wanted to include the Beatles’ forward-looking anthem “Here Comes the Sun,” but were denied because the band didn’t own the song’s copyright.

- By Andre Gee

Werewolf Billionaire CEO Husbands Are Taking Over Hollywood

- It's Giving 50 Shades

- By Ej Dickson

Alicia Keys Musical, Fleetwood Mac-Inspired Play Lead 2024 Tony Nominees

- Tony Awards 2024

- By Jon Blistein

Far-Right Influencers Celebrate Jerry Seinfeld Once Again Claiming 'PC Crap' Killed Comedy

- Old Material

- By Miles Klee

Anita Hill Pens Op-Ed Standing With Victims and Survivors Following Harvey Weinstein Reversal

- Power of Community

- By Larisha Paul

Most Popular

Ethan hawke lost the oscar for 'training day' and denzel washington whispered in his ear that losing was better: 'you don't want an award to improve your status', nicole kidman's daughters make their red carpet debut at afi life achievement award gala, louvre considers moving mona lisa to underground chamber to end 'public disappointment', sources gave an update on hugh jackman's 'love life' after fans raised concerns about his well-being, you might also like, netflix co-ceo ted sarandos among rts london convention speakers — global bulletin, bridal designer yumi katsura, who revolutionized the industry, dies, the best yoga mats for any practice, according to instructors, slamdance film festival leaving park city for los angeles in 2025, details matter: ncaa settling house and carter won’t end legal woes.

Rolling Stone is a part of Penske Media Corporation. © 2024 Rolling Stone, LLC. All rights reserved.

Verify it's you

Please log in.

- Air Transport

- Defense and Space

- Business Aviation

- Aircraft & Propulsion

- Connected Aerospace

- Emerging Technologies

- Manufacturing & Supply Chain

- Advanced Air Mobility

- Commercial Space

- Sustainability

- Interiors & Connectivity

- Airports & Networks

- Airlines & Lessors

- Safety, Ops & Regulation

- Maintenance & Training

- Supply Chain

- Workforce & Training

- Sensors & Electronic Warfare

- Missile Defense & Weapons

- Budget, Policy & Operations

- Airports, FBOs & Suppliers

- Flight Deck

- Marketplace

- Advertising

- Marketing Services

- Fleet, Data & APIs

- Research & Consulting

- Network and Route Planning

Market Sector

- AWIN - Premium

- AWIN - Aerospace and Defense

- AWIN - Business Aviation

- AWIN - Commercial Aviation

- Advanced Air Mobility Report - NEW!

- Aerospace Daily & Defense Report

- Aviation Daily

- The Weekly of Business Aviation

- Air Charter Guide

- Aviation Week Marketplace

- Route Exchange

- The Engine Yearbook

- Aircraft Bluebook

- Airportdata.com

- Airport Strategy and Marketing (ASM)

- CAPA – Centre for Aviation

- Fleet Discovery Civil

- Fleet Discovery Military

- Fleet & MRO Forecast

- MRO Prospector

- Air Transport World

- Aviation Week & Space Technology

- Aviation Week & Space Technology - Inside MRO

- Business & Commercial Aviation

- CAPA - Airline Leader

- Routes magazine

- Downloadable Reports

- Recent webinars

- MRO Americas

- MRO Australasia

- MRO Baltics & Eastern Europe Region

- MRO Latin America

- MRO Middle East

- Military Aviation Logistics and Maintenance Symposium (MALMS)

- Asia Aerospace Leadership Forum & MRO Asia-Pacific Awards

- A&D Mergers and Acquisitions

- A&D Programs

- A&D Manufacturing

- A&D Raw Materials

- A&D SupplyChain

- A&D SupplyChain Europe

- Aero-Engines Americas

- Aero-Engines Europe

- Aero-Engines Asia-Pacific

- Digital Transformation Summit

- Engine Leasing Trading & Finance Europe

- Engine Leasing, Trading & Finance Americas

- Routes Americas

- Routes Europe

- Routes World

- CAPA Airline Leader Summit - Airlines in Transition

- CAPA Airline Leader Summit - Americas

- CAPA Airline Leader Summit - Latin America & Caribbean

- CAPA Airline Leader Summit - Australia Pacific

- CAPA Airline Leader Summit - Asia & Sustainability Awards

- CAPA Airline Leader Summit - World & Awards for Excellence

- GAD Americas

- A&D Mergers and Acquisitions Conference (ADMA)

- A&D Manufacturing Conference

- Aerospace Raw Materials & Manufacturers Supply Chain Conference (RMC)

- Aviation Week 20 Twenties

- Aviation Week Laureate Awards

- ATW Airline Awards

- Program Excellence Awards and Banquet

- CAPA Asia Aviation Summit & Awards for Excellence

- Content and Data Team

- Aviation Week & Space Technology 100-Year

- Subscriber Services

- Advertising, Marketing Services & List Rentals

- Content Sales

- PR & Communications

- Content Licensing and Reprints

- AWIN Access

This article is published in Aerospace Daily & Defense Report , part of Aviation Week Intelligence Network (AWIN), and is complimentary through May 01, 2024. For information on becoming an AWIN Member to access more content like this, click here .

NASA Works To Restore Voyager 1 Engineering Data Transmissions

NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft is depicted in this artist’s concept traveling through interstellar space, which it entered in 2012.

HOUSTON—The NASA Voyager 1’s mission engineering team reports continued progress in efforts to restore the transmission of scientific data to Earth from one of the two most distant human-made objects in existence.

The Voyager 2 and 1 missions were launched from Cape Canaveralon Aug. 20 and Sept. 5, 1977, respectively, to explore Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune before departing the Solar System. Voyager 1 crossed the boundary in August 2012 and Voyager 2 in November 2018.

Last Nov. 14, Voyager 1, now more than 15 billion miles from Earth, stopped transmitting engineering and science data back to its flight team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). The engineering portion of the transmissions back to Earth resumed on April 20, thanks to some JPL detective work. It is hoped the science data soon will begin the 22.5-hr. light-speed journey back as well, according to an April 22 NASA mission update.

While Voyager 2 continues to function normally, the engineering team learned in March through limited communications that Voyager 1 had experienced a malfunction in one of the spacecraft’s three computers, the flight data system (FDS). It packages the spacecraft’s science and engineering data before they are transmitted back to Earth.

Analysis identified the problem as a chip in the FDS that stores memory, including some of the software code that had stopped working, rendering the science and engineering data unusable. Executing a remedy meant commanding a move of the affected code elsewhere in the FDS memory.

No single location within the dated FDS memory was large enough to shoulder the whole move. To address the challenge, the engineering team separated the affected code into sections and prepared them for storage at different places within the FDS, with adjustments to ensure they could function together. The portion of the coding responsible for the engineering transmissions back to Earth was moved on April 18, according to the status update.

Communications from Voyager 1 confirming success in resuming the transmission of engineering data were received back on Earth on April 20.

“During the coming weeks, the team will relocate and adjust the other affected portions of the FDS software,” the update states. “These include the portions that will start returning science data.”

Traveling on different trajectories, Voyager 1 to the north and Voyager 2 to the south, the two spacecraft are exploring the boundaries of the Sun’s sphere of influence, including those of its magnetic field and solar wind. Powered by radioisotope thermoelectric generators, the Voyagers are anticipated to function through at least 2025.

Each spacecraft also carries a “Golden Record,” a 12-in. gold-plated copper disk assembled as a form of time capsule intended to convey sounds and imagery that portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth in the event of an encounter with a distant intelligent life form.

Mark is based in Houston, where he has written on aerospace for more than 25 years. While at the Houston Chronicle, he was recognized by the Rotary National Award for Space Achievement Foundation in 2006 for his professional contributions to the public understanding of America's space program through news reporting.

- NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Related Content

Stay Connected. Stay Informed Grow Your Business.

Voyager 1 talking to Earth again after NASA engineers 24 billion kilometres away devise software fix

NASA's Voyager 1 probe — the most distant man-made object in the universe — is returning usable information to ground control following months of spouting gibberish, the US space agency says.

The spaceship stopped sending readable data back to Earth on November 14, 2023, even though controllers could tell it was still receiving their commands.

In March, teams working at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory discovered that a single malfunctioning chip was to blame.

They then had to devise a clever coding fix that worked within the tight memory constraints of its 46-year-old computer system.

"There was a section of the computer memory no longer working," project leader Dr Linda Spilker told the ABC.

"So we had to reprogram what was in that memory, move it to a different location, link everything back together and send everything up in a patch.

"And then on Saturday morning, we watched as Voyager 1 sent its first commands back and we knew we were back in communication once again."

Dr Spilker said they were receiving engineering data, so they knew the health and safety of the spacecraft.

"The next step is going to be to develop a patch so we can send back the science data," she said.

"That will really be exciting, to once again learn about interstellar space and what has been going on there that we've missed since November."

Dr Spilker said Voyager sent back data in real time, so the team had no facility to retrieve data covering the time since transmission was lost.

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 was mankind's first spacecraft to enter the interstellar medium , in 2012, and is currently more than 24 billion kilometres from Earth.

Messages sent from Earth take about 22.5 hours to reach the spacecraft.

Its twin, Voyager 2, also left the solar system in 2018 as it was tracked by Australia's Parkes radio telescope.

Australia was also vital to a 2023 search for Voyager 2 after signals were lost, with Canberra's Deep Space Communication Complex monitoring for signals and then sending a successful command to shift the spacecraft's antenna 2 degrees .

Both Voyager spacecraft carry " Golden Records ": 12-inch, gold-plated copper disks intended to convey the story of our world to extraterrestrials.

These include a map of our solar system, a piece of uranium that serves as a radioactive clock allowing recipients to date the spaceship's launch, and symbolic instructions that convey how to play the record.

The contents of the record, selected for NASA by a committee chaired by legendary astronomer Carl Sagan, include encoded images of life on Earth, as well as music and sounds that can be played using an included stylus.

Their power banks were expected to be depleted sometime after 2025, but Dr Spilker said several systems had been turned off, so they were hopeful the two spacecraft would function into the 2030s.

They will then continue to wander the Milky Way, potentially for eternity, in silence.

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

Nasa restores contact with missing voyager 2 spacecraft after weeks of silence.

How songs from tiny villages in the Pacific are now floating in outer space

Voyager 1 spacecraft enters interstellar space

- Astronomy (Space)

- Computer Science

- Space Exploration

- United States

VOYAGER GOLDEN RECORD

- The Contents

- The Making of

- Where Are They Now

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Q & A with Ed Stone

golden record

Where are they now.

- frequently asked questions

- Q&A with Ed Stone

golden record / whats on the record

Music from earth.

The following music was included on the Voyager record.

- Bach, Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F. First Movement, Munich Bach Orchestra, Karl Richter, conductor. 4:40

- Java, court gamelan, "Kinds of Flowers," recorded by Robert Brown. 4:43

- Senegal, percussion, recorded by Charles Duvelle. 2:08

- Zaire, Pygmy girls' initiation song, recorded by Colin Turnbull. 0:56

- Australia, Aborigine songs, "Morning Star" and "Devil Bird," recorded by Sandra LeBrun Holmes. 1:26

- Mexico, "El Cascabel," performed by Lorenzo Barcelata and the Mariachi México. 3:14

- "Johnny B. Goode," written and performed by Chuck Berry. 2:38

- New Guinea, men's house song, recorded by Robert MacLennan. 1:20

- Japan, shakuhachi, "Tsuru No Sugomori" ("Crane's Nest,") performed by Goro Yamaguchi. 4:51

- Bach, "Gavotte en rondeaux" from the Partita No. 3 in E major for Violin, performed by Arthur Grumiaux. 2:55

- Mozart, The Magic Flute, Queen of the Night aria, no. 14. Edda Moser, soprano. Bavarian State Opera, Munich, Wolfgang Sawallisch, conductor. 2:55

- Georgian S.S.R., chorus, "Tchakrulo," collected by Radio Moscow. 2:18

- Peru, panpipes and drum, collected by Casa de la Cultura, Lima. 0:52

- "Melancholy Blues," performed by Louis Armstrong and his Hot Seven. 3:05

- Azerbaijan S.S.R., bagpipes, recorded by Radio Moscow. 2:30

- Stravinsky, Rite of Spring, Sacrificial Dance, Columbia Symphony Orchestra, Igor Stravinsky, conductor. 4:35

- Bach, The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 2, Prelude and Fugue in C, No.1. Glenn Gould, piano. 4:48

- Beethoven, Fifth Symphony, First Movement, the Philharmonia Orchestra, Otto Klemperer, conductor. 7:20

- Bulgaria, "Izlel je Delyo Hagdutin," sung by Valya Balkanska. 4:59

- Navajo Indians, Night Chant, recorded by Willard Rhodes. 0:57

- Holborne, Paueans, Galliards, Almains and Other Short Aeirs, "The Fairie Round," performed by David Munrow and the Early Music Consort of London. 1:17

- Solomon Islands, panpipes, collected by the Solomon Islands Broadcasting Service. 1:12

- Peru, wedding song, recorded by John Cohen. 0:38

- China, ch'in, "Flowing Streams," performed by Kuan P'ing-hu. 7:37

- India, raga, "Jaat Kahan Ho," sung by Surshri Kesar Bai Kerkar. 3:30

- "Dark Was the Night," written and performed by Blind Willie Johnson. 3:15

- Beethoven, String Quartet No. 13 in B flat, Opus 130, Cavatina, performed by Budapest String Quartet. 6:37

Inside NASA's 5-month fight to save the Voyager 1 mission in interstellar space

After working for five months to re-establish communication with the farthest-flung human-made object in existence, NASA announced this week that the Voyager 1 probe had finally phoned home.

For the engineers and scientists who work on NASA’s longest-operating mission in space, it was a moment of joy and intense relief.

“That Saturday morning, we all came in, we’re sitting around boxes of doughnuts and waiting for the data to come back from Voyager,” said Linda Spilker, the project scientist for the Voyager 1 mission at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “We knew exactly what time it was going to happen, and it got really quiet and everybody just sat there and they’re looking at the screen.”

When at long last the spacecraft returned the agency’s call, Spilker said the room erupted in celebration.

“There were cheers, people raising their hands,” she said. “And a sense of relief, too — that OK, after all this hard work and going from barely being able to have a signal coming from Voyager to being in communication again, that was a tremendous relief and a great feeling.”

The problem with Voyager 1 was first detected in November . At the time, NASA said it was still in contact with the spacecraft and could see that it was receiving signals from Earth. But what was being relayed back to mission controllers — including science data and information about the health of the probe and its various systems — was garbled and unreadable.

That kicked off a monthslong push to identify what had gone wrong and try to save the Voyager 1 mission.

Spilker said she and her colleagues stayed hopeful and optimistic, but the team faced enormous challenges. For one, engineers were trying to troubleshoot a spacecraft traveling in interstellar space , more than 15 billion miles away — the ultimate long-distance call.

“With Voyager 1, it takes 22 1/2 hours to get the signal up and 22 1/2 hours to get the signal back, so we’d get the commands ready, send them up, and then like two days later, you’d get the answer if it had worked or not,” Spilker said.

The team eventually determined that the issue stemmed from one of the spacecraft’s three onboard computers. Spilker said a hardware failure, perhaps as a result of age or because it was hit by radiation, likely messed up a small section of code in the memory of the computer. The glitch meant Voyager 1 was unable to send coherent updates about its health and science observations.

NASA engineers determined that they would not be able to repair the chip where the mangled software is stored. And the bad code was also too large for Voyager 1's computer to store both it and any newly uploaded instructions. Because the technology aboard Voyager 1 dates back to the 1960s and 1970s, the computer’s memory pales in comparison to any modern smartphone. Spilker said it’s roughly equivalent to the amount of memory in an electronic car key.

The team found a workaround, however: They could divide up the code into smaller parts and store them in different areas of the computer’s memory. Then, they could reprogram the section that needed fixing while ensuring that the entire system still worked cohesively.

That was a feat, because the longevity of the Voyager mission means there are no working test beds or simulators here on Earth to test the new bits of code before they are sent to the spacecraft.

“There were three different people looking through line by line of the patch of the code we were going to send up, looking for anything that they had missed,” Spilker said. “And so it was sort of an eyes-only check of the software that we sent up.”

The hard work paid off.

NASA reported the happy development Monday, writing in a post on X : “Sounding a little more like yourself, #Voyager1.” The spacecraft’s own social media account responded , saying, “Hi, it’s me.”

So far, the team has determined that Voyager 1 is healthy and operating normally. Spilker said the probe’s scientific instruments are on and appear to be working, but it will take some time for Voyager 1 to resume sending back science data.

Voyager 1 and its twin, the Voyager 2 probe, each launched in 1977 on missions to study the outer solar system. As it sped through the cosmos, Voyager 1 flew by Jupiter and Saturn, studying the planets’ moons up close and snapping images along the way.

Voyager 2, which is 12.6 billion miles away, had close encounters with Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune and continues to operate as normal.

In 2012, Voyager 1 ventured beyond the solar system , becoming the first human-made object to enter interstellar space, or the space between stars. Voyager 2 followed suit in 2018.

Spilker, who first began working on the Voyager missions when she graduated college in 1977, said the missions could last into the 2030s. Eventually, though, the probes will run out of power or their components will simply be too old to continue operating.

Spilker said it will be tough to finally close out the missions someday, but Voyager 1 and 2 will live on as “our silent ambassadors.”

Both probes carry time capsules with them — messages on gold-plated copper disks that are collectively known as The Golden Record . The disks contain images and sounds that represent life on Earth and humanity’s culture, including snippets of music, animal sounds, laughter and recorded greetings in different languages. The idea is for the probes to carry the messages until they are possibly found by spacefarers in the distant future.

“Maybe in 40,000 years or so, they will be getting relatively close to another star,” Spilker said, “and they could be found at that point.”

Denise Chow is a reporter for NBC News Science focused on general science and climate change.

After months of silence, Voyager 1 has returned NASA’s calls

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

For the last five months, it seemed very possible that a 46-year-old conversation had finally reached its end.

Since its launch from Kennedy Space Center on Sept. 5, 1977, NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft has diligently sent regular updates to Earth on the health of its systems and data collected from its onboard instruments.

But in November, the craft went quiet.

Voyager 1 is now some 15 billion miles away from Earth. Somewhere in the cold interstellar space between our sun and the closest stars, its flight data system stopped communicating with the part of the probe that allows it to send signals back to Earth. Engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge could tell that Voyager 1 was getting its messages, but nothing was coming back.

“We’re to the point where the hardware is starting to age,” said Linda Spilker, the project scientist for the Voyager mission. “It’s like working on an antique car, from 15 billion miles away.”

Week after week, engineers sent troubleshooting commands to the spacecraft, each time patiently waiting the 45 hours it takes to get a response here on Earth — 22.5 hours traveling at the speed of light to reach the probe, and 22.5 hours back.

Science & Medicine

This space artist created the Golden Record and changed the way we see the universe

Space artist Jon Lomberg has produced work that attempts to visualize what we can’t truly see, and to communicate with creatures we can’t yet imagine.

July 26, 2023

By March, the team had figured out that a memory chip that stored some of the flight data system’s software code had failed, turning the craft’s outgoing communications into gibberish.

A long-distance repair wasn’t possible. There wasn’t enough space anywhere in the system to shift the code in its entirety. So after manually reviewing the code line by line, engineers broke it up and tucked the pieces into the available slots of memory.

They sent a command to Voyager on Thursday. In the early morning hours Saturday, the team gathered around a conference table at JPL: laptops open, coffee and boxes of doughnuts in reach.

At 6:41 a.m., data from the craft showed up on their screens. The fix had worked .

“We went from very quiet and just waiting patiently to cheers and high-fives and big smiles and sighs of relief,” Spilker said. “I’m very happy to once again have a meaningful conversation with Voyager 1.”

Voyager 1 is one of two identical space probes. Voyager 2, launched two weeks before Voyager 1, is now about 13 billion miles from Earth, the two crafts’ trajectories having diverged somewhere around Saturn. (Voyager 2 continued its weekly communications uninterrupted during Voyager 1’s outage.)

Space shuttle Endeavour is lifted into the sky, takes final position as star of new museum wing

A shrink-wrapped Endeavour was hoisted and then carefully placed in its final location Tuesday at the still-under-construction Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center.

Jan. 30, 2024

They are the farthest-flung human-made objects in the universe, having traveled farther from their home planet than anything else this species has built. The task of keeping communications going grows harder with each passing day. Every 24 hours, Voyager 1 travels 912,000 miles farther away from us. As that distance grows, the signal becomes slower and weaker.

When the probe visited Jupiter in 1979, it was sending back data at a rate of 115.2 kilobits per second, Spilker said. Today, 45 years and more than 14 billion miles later, data come back at a rate of 40 bits per second.

The team is cautiously optimistic that the probes will stay in contact for three more years, long enough to celebrate the mission’s 50th anniversary in 2027, Spilker said. They could conceivably last until the 2030s.

The conversation can’t last forever. Microscopic bits of silica keep clogging up the thrusters that keep the probes’ antennas pointed toward Earth, which could end communications. The power is running low. Eventually, the day will come when both Voyagers stop transmitting data to Earth, and the first part of their mission ends.

But on the day each craft goes quiet, they begin a new era, one that could potentially last far longer. Each probe is equipped with a metallic album cover containing a Golden Record , a gold-plated copper disk inscribed with sounds and images meant to describe the species that built the Voyagers and the planet they came from.

Erosion in space is negligible; the images could be readable for another billion years or more. Should any other intelligent life form encounter one of the Voyager probes and have a means of retrieving the data from the record, they will at the very least have a chance to figure out who sent them — even if our species is by that time long gone.

JPL tries to keep Voyager space probes from disconnecting the world’s longest phone call

Keeping in touch with NASA’s two aging Voyager spacecraft is getting harder to do as they get farther away and their power sources dwindle.

Sept. 3, 2022

More to Read

Too expensive, too slow: NASA asks for help with JPL’s Mars Sample Return mission

April 15, 2024

NASA’s attempt to bring home part of Mars is unprecedented. The mission’s problems are not

March 25, 2024

Budget deal for NASA offers glimmer of hope for JPL’s Mars Sample Return mission

March 6, 2024

Corinne Purtill is a science and medicine reporter for the Los Angeles Times. Her writing on science and human behavior has appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, Time Magazine, the BBC, Quartz and elsewhere. Before joining The Times, she worked as the senior London correspondent for GlobalPost (now PRI) and as a reporter and assignment editor at the Cambodia Daily in Phnom Penh. She is a native of Southern California and a graduate of Stanford University.

More From the Los Angeles Times

More than 50 are injured when L.A. Metro train, bus collide outside Exposition Park

April 30, 2024

A 17-year-old girl was fatally shot while walking home in Long Beach. Police release video of a suspect

The scrappiest place on Earth? Altercation at Disney California Adventure leads to ejection

Why the Lakers lost their last timeout despite successful challenge against Nuggets

Cornell Chronicle

- Architecture & Design

- Arts & Humanities

- Business, Economics & Entrepreneurship

- Computing & Information Sciences

- Energy, Environment & Sustainability

- Food & Agriculture

- Global Reach

- Health, Nutrition & Medicine

- Law, Government & Public Policy

- Life Sciences & Veterinary Medicine

- Physical Sciences & Engineering

- Social & Behavioral Sciences

- Coronavirus

- News & Events

- Public Engagement

- New York City

- Photos of the Week

- Big Red Sports

- Freedom of Expression

- Student Life

- University Statements

- Around Cornell

- All Stories

- In the News

- Expert Quotes

- Cornellians

“Science Guy” Bill Nye ’77 recalled the state of mechanical engineering when he was a student and looked ahead to the field’s future at “Sibley 150,” a celebration of 150 years of mechanical engineering at Cornell.

Slide rules, sundials and comedy: Bill Nye hails scientific solutions

By david nutt, cornell chronicle.

The way Bill Nye ’77 tells it, he was an unpromising student admitted to Cornell due to a “some sort of clerical error” when he made a historic contribution to interstellar exploration.

As a senior, having completed his mechanical engineering requirements to the “great relief for everybody,” Nye was taking Astronomy 102 with “this famous guy, Carl Sagan .” In class, Sagan announced he was planning to include “Roll Over Beethoven” by Chuck Berry on the Voyager spacecrafts’ fabled Golden Record – but Nye insisted “Johnny B. Goode” would be the better choice.

Sure enough, that’s what is on the Voyager record.

During a Q&A session, an audience member asked how young people will solve global warming, to which Nye responded: clean water, renewable electricity and access to the internet.

“I take full credit for that,” Nye said, during the keynote address for “Sibley 150,” a celebration of 150 years of mechanical engineering at Cornell held April 25. “That’s why I went to engineering school, to get ‘Johnny B. Goode’ in the cosmos, so that alien entities could enjoy early rock-n-roll.”

A beloved science-education advocate and a famous guy in his own right, Nye gave a Janus-like view of the state of mechanical engineering, looking back to when he graduated in 1977 and peering ahead to the field’s future: the challenges it faces and the solutions that science offers.

Assisted by a slideshow, a few props – including a slide rule – and his giddy wit, Nye led the audience in Philips Hall on a tour of his formative experiences at Cornell and the surprising trajectory of his life after graduation. Nye recalled taking ballroom dancing for a physical education requirement, a skill that served him well, decades later, when he appeared on Dancing with the Stars – and subsequently tore his quadriceps tendon. Just as enduring has been his enthusiasm for Ultimate Frisbee. He played on Cornell’s first Ultimate team in 1973.

“I’m first to admit, everybody, Ultimate ain’t much of a name for a sport … We tried to have ‘flatball,’ but that didn’t catch on,” he said.

He spoke movingly of his professors, including Sagan and the “eccentric” Richard Phelan, M.S. ’50, who, with President Emeritus Dale Corson – “a heck of a guy” responsible for planning the Arecibo Observatory – designed the sundial on the Engineering quad.

Nye delved into his own love for, and deeply personal connection to, those old-fashioned devices. Nye’s father, Edwin Darby Nye, had relied on sundials as a prisoner of war for 44 months, and he went on to write a book, “Sundials of Maryland and Virginia,” which Nye playfully suggested would be of some use “if you’re having trouble sleeping.”

The younger Nye channeled that interest into helping design three sundials for the Mars Exploration Rover, as well as the Solar Noon Clock for Rhodes Hall.

“It’s all just part of how Cornell has affected me. The dancing, the sun dial, the clock, the Mars dials. Cornell has changed my life. Cornell has made me who I am. That’s not all good,” he said, to a burst of laughter. “I cannot thank Cornell enough for that mistake in the admissions department, and everything that’s happened since then.”

‘We can – dare I say it – change the world’

1977 was a significant year in Nye’s life, and for science. He graduated from Cornell. The Voyager spacecraft were launched. And people were already tracking the rise in global temperature that would result in the current climate crisis.

“Fifty years ago, people saw climate change coming,” he said. “And I’m hip. Young people, when you say ‘OK, Boomer, what have you done?’ Almost nothing. And so it is going to be up to you guys.”

Upon graduation, Nye took an engineering job at Boeing for $15,000 a year – nowadays students “drop $15,000 at Collegetown Bagels,” he joked. He specialized in hydraulics systems on 747s and even spent some time working on Air Force One because there was a vibration that rankled one of the pilots.

“It was the thing they give the young guy who can still do math,” he said.

However, engineering wasn’t his sole focus. While living in Seattle, Nye entered and won a regional Steve Martin lookalike contest sponsored by the comedian’s record company. (Nye lost the national competition to a man from Nashville who could play the banjo.)

“After I won this contest, people wanted me to be Steve Martin at a party or an event,” he said. “And you know, I’m not Steve Martin, because he’s really funny. But what do I have? That’s right. I’m funny looking. So I started trying to do comedy.”

Nye would work at Boeing during the day, go home and take a nap, then venture out to comedy clubs at night. Soon he was submitting jokes to a Seattle television show called Almost Live!, where he eventually debuted as “the Science Guy” – combining his knack for comedy with his passion for science.

“This was my first bit as a science guy,” the perpetually bow-tied Nye said, as he flashed an image of that early television appearance. “And you can see, I’m wearing a straight tie. It’s so weird.”

There was one emblem of the 1970s that Nye found particularly troubling: the infamous Ford Pinto, which had a reputation for exploding during rear-end collisions.

“This really bothered me as an engineer, that this was considered acceptable in the U.S.,” Nye said.

Nye poses with student assistants from “Sibley 150” following his keynote address.

Nye launched his “Science Guy” show, which went on to win 19 Emmy Awards, to get children excited about science and solve those types of problems.