- Become A Member

- Gift Membership

- Kids Membership

- Other Ways to Give

- Explore Worlds

- Defend Earth

How We Work

- Education & Public Outreach

- Space Policy & Advocacy

- Science & Technology

- Global Collaboration

Our Results

Learn how our members and community are changing the worlds.

Our citizen-funded spacecraft successfully demonstrated solar sailing for CubeSats.

Space Topics

- Planets & Other Worlds

- Space Missions

- Space Policy

- Planetary Radio

- Space Images

The Planetary Report

The eclipse issue.

Science and splendor under the shadow.

Get Involved

Membership programs for explorers of all ages.

Get updates and weekly tools to learn, share, and advocate for space exploration.

Volunteer as a space advocate.

Support Our Mission

- Renew Membership

- Society Projects

The Planetary Fund

Accelerate progress in our three core enterprises — Explore Worlds, Find Life, and Defend Earth. You can support the entire fund, or designate a core enterprise of your choice.

- Strategic Framework

- News & Press

The Planetary Society

Know the cosmos and our place within it.

Our Mission

Empowering the world's citizens to advance space science and exploration.

- Explore Space

- Take Action

- Member Community

- Account Center

- “Exploration is in our nature.” - Carl Sagan

Jake Rosenthal • Jan 20, 2016

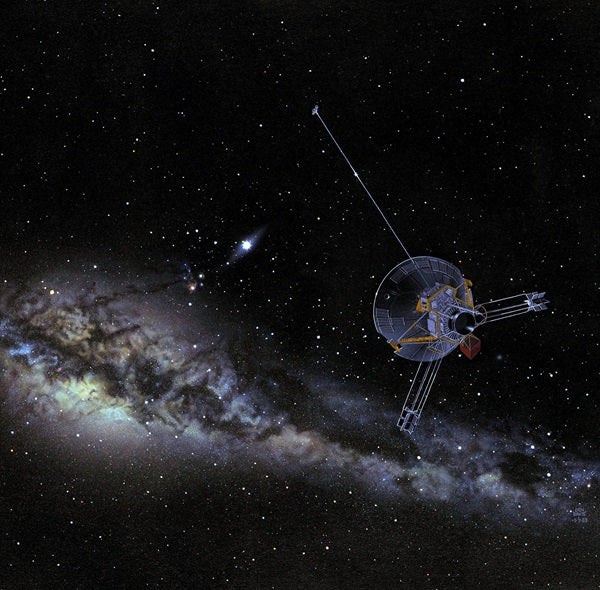

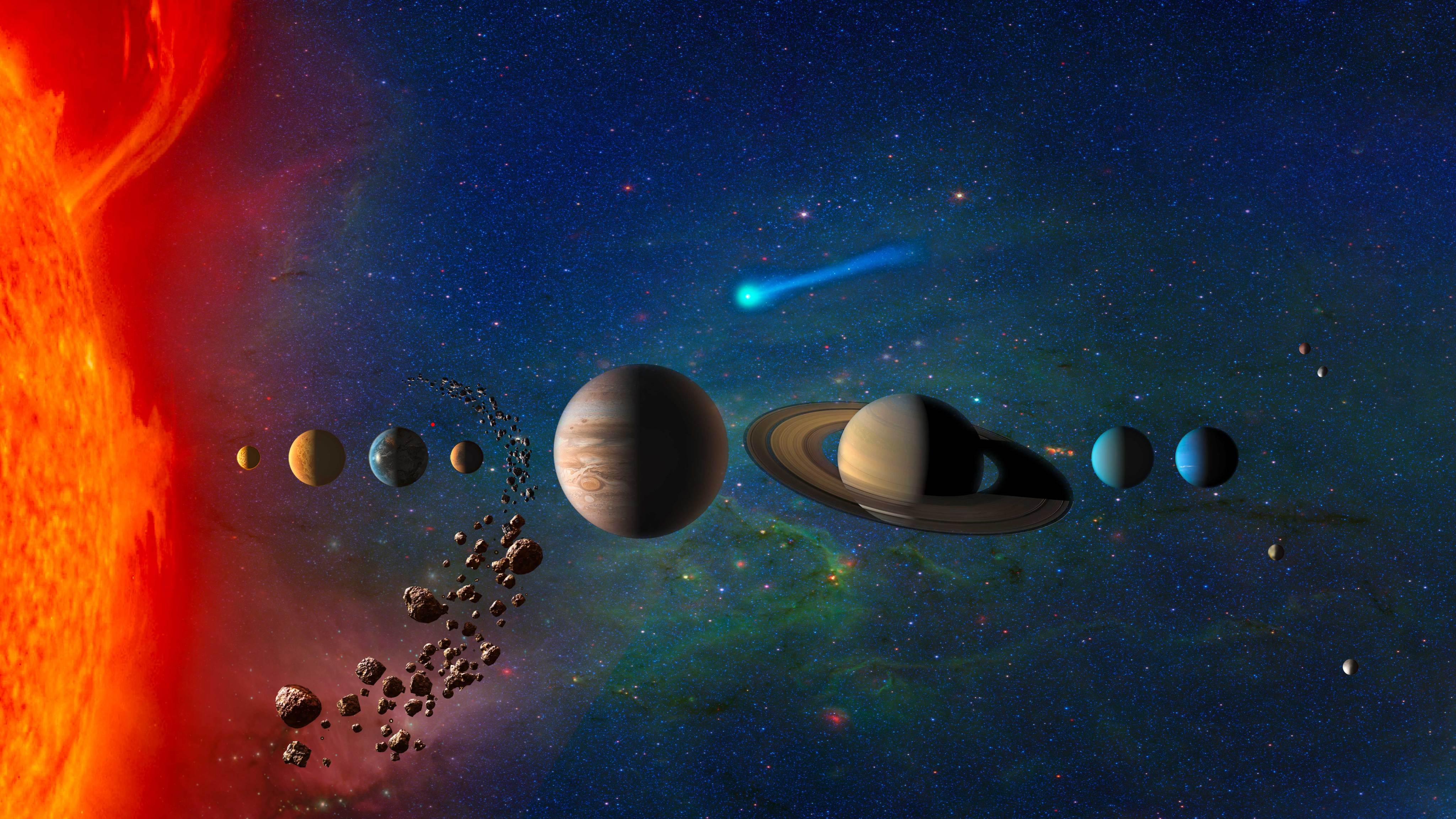

The Pioneer Plaque: Science as a Universal Language

In 1972, an attempt to contact extraterrestrial life was cast into space with the launch of the Pioneer 10 spacecraft. This space vehicle was designed to explore the environment of Jupiter, along with asteroids, solar winds, and cosmic rays. Among a succession of firsts achieved by the spacecraft, Pioneer 10 would attain enough velocity to escape the solar system. This tacked on yet another first: the possibility of the interception of a human machine by an extraterrestrial civilization, providing us the opportunity to make contact with life from another world.

The suggestion of a message on Pioneer 10 was brought to Dr. Carl Sagan mere months before launch—a staggeringly brief period in the timescale of the design and test of spacecraft. Sagan passed along the idea to NASA, and to his surprise, the suggestion was embraced and approved by every level of the hierarchy. At that, Sagan joined Professor Frank Drake of Cornell University and, Sagan’s then-wife, artist Linda Salzman Sagan, to craft this extraterrestrial message. How would this great undertaking be fulfilled? What would we say? What in our roughly five-thousand-year recorded history needs to be said to tell the universe who we are? And how would we say it?

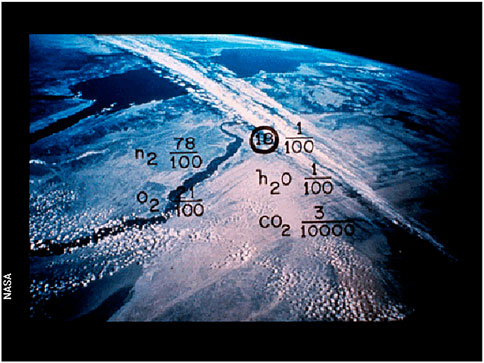

Humans speak nearly seven thousand languages, some with multiple dialects. The countless other species on Earth communicate with innumerably more, nearly all of which we have, thus far, failed to understand. By extrapolation, it is presumable that an alien language is different than any language we have developed. Human languages are products of human minds, and thereby, can be understood by human minds, by means of human senses—sight, sound, touch. How could we begin to imagine an extraterrestrial language if we cannot imagine with what senses the beings communicate? They may not have vocal chords with which they produce sounds or ears with which they capture them. So we must rely on universally-understood concepts, and devise a communication method neither specific to location nor species nor world. Perhaps, the only similarity between our species is the universe in which we both live. Thus, the language we are most likely to share is the study of the universe itself: science. The result of this conclusion was the Pioneer Plaque.

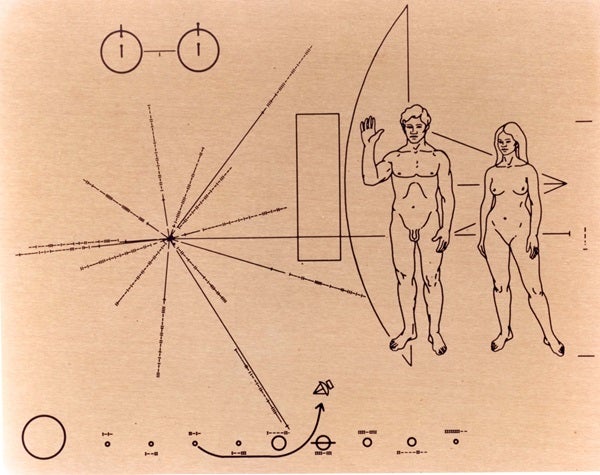

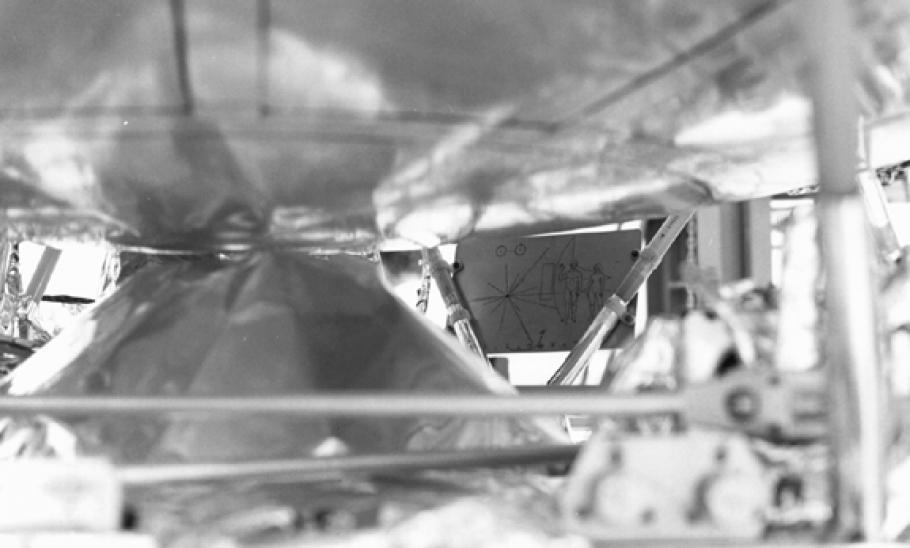

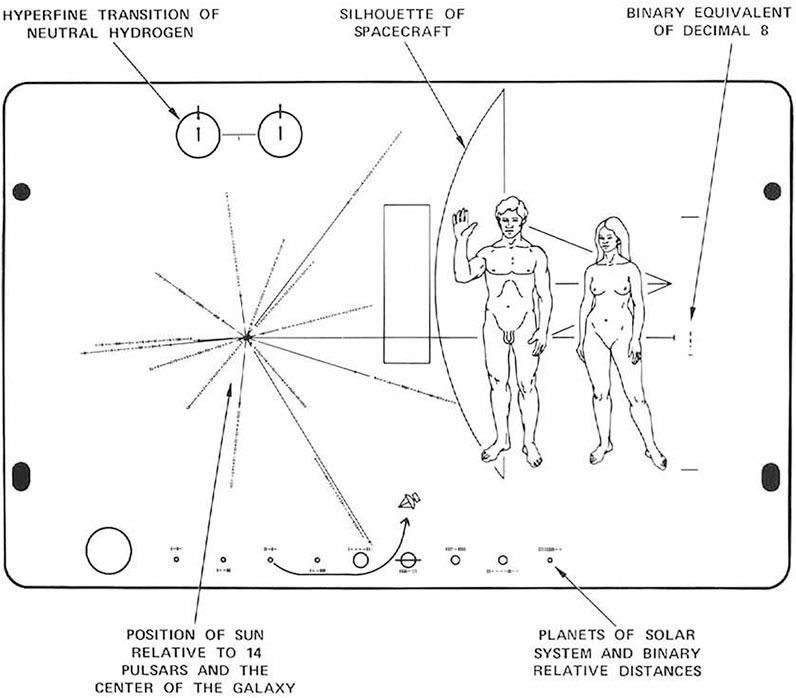

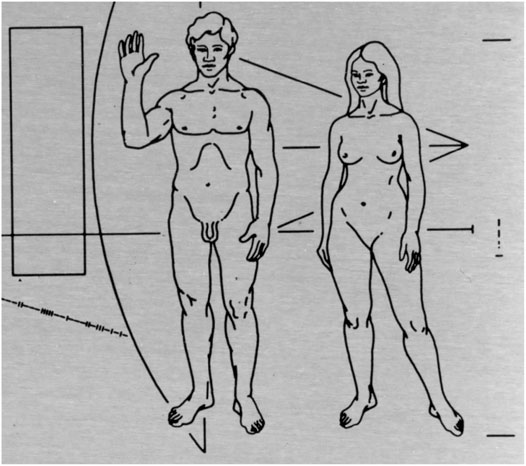

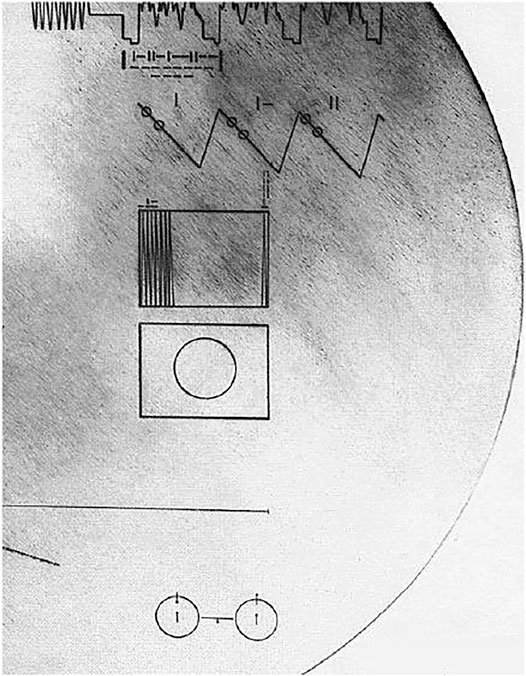

The Pioneer Plaque is a physical, symbolic message affixed to the exterior of the Pioneer 10 spacecraft. At the core of this message is a fundamental concept that establishes a standard of distance and time, which, thereafter, is employed by the other components of the plaque. The design team postulated that hydrogen, being the most abundant element in the cosmos, would be one of the first elements to be studied by a civilization. With this in mind, they inscribed two hydrogen atoms at the top left of the plaque, each in a different energy state. When atoms of hydrogen change from one energy state to another—a process called the hyperfine transition—electromagnetic radiation is released. It is this wave that harbors the standard of measure used throughout the illustrations on the plaque. The wavelength (approximately 21 centimeters) serves as a spatial measurement, and the period (approximately .7 nanoseconds) serves as a measurement of time. The final detail of this schematic is a small tick between the atoms of hydrogen, assigning these values of distance and time to the binary number 1.

The most prominent figures on the plaque are those of two adult humans: a man and woman. The man bends his arm and displays an open palm—an international greeting, but one that, admittedly, may be meaningless to an extraterrestrial civilization. The woman hangs her arms by her sides and stands with her weight shifted rearward as to dispel any misunderstandings regarding a fixed body and limb position; we are mobile and flexible. Beside the illustrations of the humans is the binary number 8, inscribed between two ticks, indicating the height the woman. The civilization could then conclude that the woman is 8 units tall, the unit being the wavelength (21 centimeters) described by the hyperfine transition key; thus, the woman is 8 times 21 centimeters, or about 5.5 feet tall.

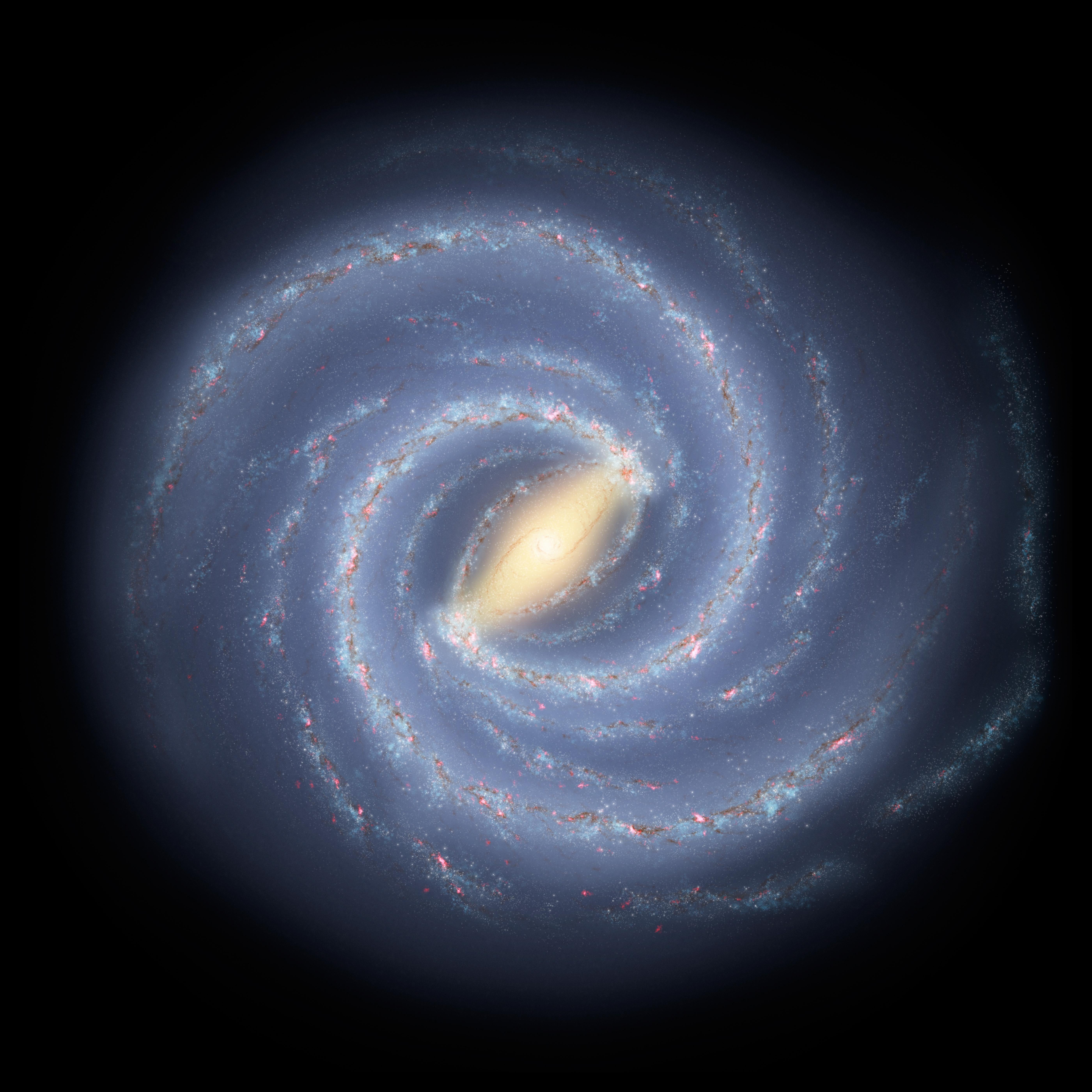

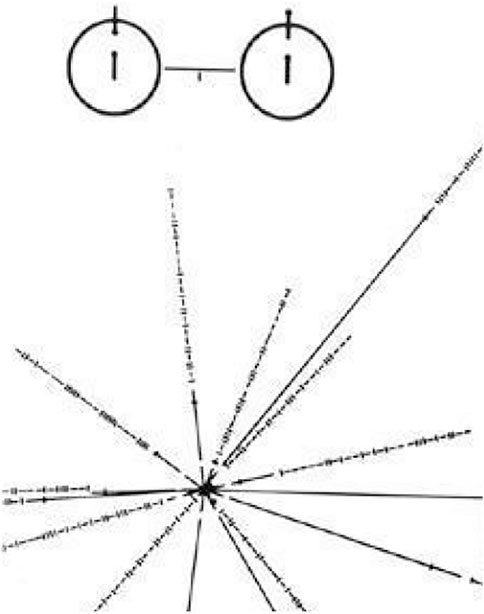

At the heart of the plaque is an array of lines and dashes—a cosmic address on the interstellar letter. In the center is our home star; the radial spokes signify the relative distances and directions to pulsars—rapidly rotating neutron stars that emit electromagnetic radiation at regular intervals. Accompanying each line is the period of the respective pulsar—once again, in binary. Not only does this map communicate position, but time as well—an epoch in the lifetime of the universe during which the message was sent. The rate of electromagnetic bursts from pulsars changes over time; thus, the period of the pulsars denoted on the plaque serves as a timestamp. It is presumed that a civilization that has developed radio astronomy will have the capability to comprehend the nature of pulsars. Given the information presented in the pulsar map, it is feasible that such a civilization could date back the message and triangulate our position. As further confirmation of our locale, our solar system’s planets (nine at the time) are depicted in the bottom margin of the plaque with their respective distances to the sun in binary. Supposedly, in the history of the Milky Way, only one star has ever fit the characteristics displayed on the plaque.

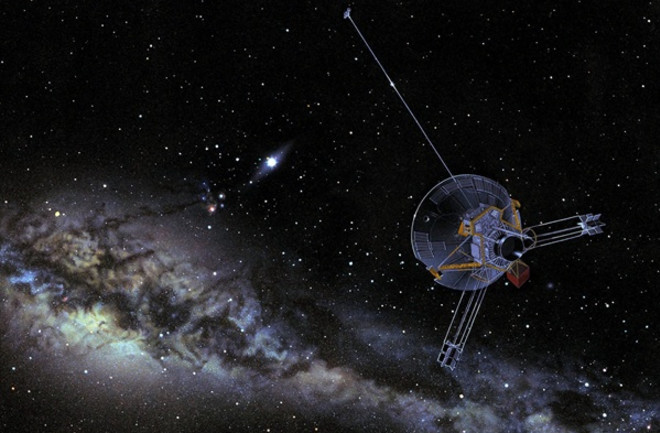

The last signal from the Pioneer 10 spacecraft was received on January 22, 2003; NASA reported that the power source had depleted. Although the spacecraft can no longer speak to us, it presses onward—it now speaks for us. As interstellar courier, it bears the accumulated voice of every human, transcribed in, perhaps, the only common language in all the cosmos. We are but cosmic toddlers just learning how to take our first steps into space, and just learning how to speak to the universe.

Since Pioneer 10 was directed neither to an exoplanet nor a star, contact is extremely unlikely. But if, by the merest happenstance, the spacecraft is intercepted by an alien species, there is at least a chance that the species can interpret our message. In all likelihood however, Pioneer 10 and its plaque will be lost in the immense tranquility of empty space. But in no case was our attempt for naught. Pioneer 10 remains more than just a ghost of a ship, and the plaque is more than a shout into the void. The message we sent to the universe still echoes in our ears. Born from such a mission—one that spans space, time, and perhaps, civilizations—is a new mindset, an otherworldly perspective.

From the vantage of a distant world, our sun will be just another star, and our planet hidden in the radiance of the stellar glow. On such a world—one so distant and different from our own—we have not the slightest indication of what life will be like, how it began, how it evolved. If beings were to emerge, we know not their anatomy nor biology nor psychology, their physical traits, their sensory capabilities, their intellectual sophistication, their disposition; more or less, we are blind to every aspect of their species. They could be different in every way—in ways we have yet to understand or could even imagine. We make numerous assumptions about what life is and what life is not—educated guesses based off a sample size of one. But if, in some form or another, advanced consciousness arises elsewhere in the cosmos, it is possible that those beings will wonder, as we did: What are the lights in the sky? Where did the planets come from? What else is out there? Who else is out there? They may compile a system of knowledge of the cosmos and the laws that govern it; we call this “science.” About this hypothetical species, we know but one thing: the science they develop—the natural laws they discover—if they were to do so, would be exactly the same as our own.

Although not every human conducts science, it is conducted for every human. Science speaks to all of us in a way nothing ever has. It sparks new ideas and alternate perspectives. It brings each of us together and all of us forward. It is, at the very least, an international language, because there is an implied assertion with every question: there is something we do not know; and with our missions, we learn together. We probe the unknown looking for answers, venturing to understand the universe as it is—not the way we want it or believe it to be. Every step of the way, we strive not to fit the universe to the limits of our minds, but stretch our minds to the limitlessness of the universe.

For every great scientific discovery and technological advancement, there was a time before, when the universe was a little less known. The significance and brilliance of our technologies and the science that drives them is too often overlooked. We forget the time before—a time without cell phones and personal computers, automobiles and airplanes—during which we wondered what it would be like to communicate at the speed of light and fly around to the other side of the planet in a matter of hours. Right now, at this time, we wonder what it would be like to find life elsewhere in the cosmos and to make first contact. This is the time before that great discovery, and there will be a time after. Maybe in the near future, or maybe a more distant one, it will be commonplace to carry on conversations with extraterrestrials; and again, we will forget how, right now, we are ceaselessly wondering, in endless search for an answer.

A Message from Earth , by Carl Sagan, Linda Salzman Sagan, and Frank Drake

The Cosmic Connection , by Carl Sagan

PIONEER 10 SPACECRAFT SENDS LAST SIGNAL , by Michael Mewhinney

Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

For full functionality of this site it is necessary to enable JavaScript. Here are instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your web browser .

Fill your inbox with inspiring stories every week.

Vertical Thrust:The Story of NASA’sLegendary Logo Design

Subscribe now..

Ceros Inspire is where creative marketing meets interactive design. Get a fresh batch of stories delivered to your inbox weekly.

Looking to create more engaging digital content?

Ceros is the best way to create interactive content without writing a single line of code.

DIY Time Traveler’s Guide to Surviving History

So, You’re Lost in Space: How to Read the Pioneer Plaque

- December 4, 2020

From out of space…a postcard?

This week, begin to decipher the cryptic symbols engraved on the face of the plaque which accompanies Pioneer 10 out of the familiar solar system and into undiscovered space

History and Composition

In 1973, one year after it was launched on February 27, 1972, the Pioneer 10 spacecraft became the first manmade object to leave the Earth’s solar system. The spacecraft was created to study Jupiter where the spacecraft would then use the immense momentum created by the gas giant to propel itself out of the solar system. Pioneer 10 is a small spacecraft, measuring in at 2.9 meters (9.5 feet) tall, only slightly taller than any unfortunate chrononaut that may find it floating in interstellar space, and it is relatively light at 258 kilograms (570 pounds). Since 1972, the spacecraft has trekked faithfully through the empty expanse of space towards the star Aldebaran—the eye of Taurus—about 65 light years away from Earth, powered by four radioisotope thermoelectric generators. While it is traveling around 11.5 km/second (about 25,700 mph) Pioneer 10 will take more than 2 million years to reach the celestial neighbor. Intended as a scientific instrument, it was known during its construction that Pioneer 10 would become the first manmade object to leave the familiar solar system for destinations unknown. In a spark of inspiration, it was agreed that in the unlikely chance it would be discovered by intelligent life, the spacecraft would be equipped with a simple greeting card from humanity. The engraving was designed in 3 short weeks by Carl Sagan, Frank Drake (of Drake Equation fame), and Linda Salzman Sagan. The 6-inch-by-9-inch (15.24 by 22.86 cm) plate is mounted externally on the antenna support structure, behind the ARC plasma experimental package. The Pioneer Plaque is 0.05 inches thick made of 6061 T6 gold-anodized aluminum plate, intended to be durable enough to endure the rough interstellar voyage. The message on the plaque is etched ~10 -2 cm deep, so the symbols would remain readable even after the accumulated damage barrage of micrometeorites over the travel distance of ~10 parsecs* (32.6156 light years), and possibly as far as 100 parsecs (326.156 light years)

Hyperfine Transition of Hydrogen

To begin deciphering the Pioneer Plaque, the top left diagram is the most important as it represents the legend and “universal yardstick” that will be used throughout the diagram. Rather than any specific language, the Pioneer Plaque uses mathematics as a universal language. It could be assumed that any technologically-advanced intelligence capable of catching the spacecraft would also be familiar with some common scientific features in space, most importantly, the characteristics of hydrogen, as it is the most abundant element in the universe. The two circles represent the same hydrogen atom in different states. This symbol represents the 21-cm hyperfine transition of neutral atomic hydrogen.

The hyperfine transition in neutral hydrogen atoms occurs when the atoms change energy states and electromagnetic radiation energy is released at a precise wavelength. The transition of these states is represented by the inverted symbols on the top of circles displaying the antiparallel to parallel nuclear and electronic spins. As a wavelength, the change in energy states can represent two potential values: a unit of length (21 cm) or a unit of time (1450 hz). This creates a legend for the hydrogen-based cipher that is used throughout the diagram. The transition between each state is connected by a line in the diagram with the binary digit for 1 below to represent this transition as a binary value. The binary values used throughout the diagram represent either the length of time value of the hydrogen cipher

Binary Translation

Binary was chosen as an interstellar language on the plaque since it is the simplest representation of numbers and can survive long periods of time under the predicted erosion caused by micrometeorites in its path along the interstellar journey.

Binary is a base two system, where a value can either be 0 or 1. It is read from left to right, where the position of the value (n) represents the value 2 n . The values for each position are multiplied by 2 n and finally added together to get the final value. For example, the binary value below is 100111 represents the integer value 39:

Each string of binary values on the diagram can be assumed to be read in either direction, making the true translation slightly obscured at first glance. However, since the string of binary values are displayed in the order of most significant digits, they all start with 1 and end in 1 or 0.

For example, on the far right center of the diagram, next to the women’s figure is the value either 0001 or 1000 in binary. Since the string must start with 1, the most significant digit, the value in binary is ‘1000’ representing the integer value of 8.

Once translated from binary to an integer value, the value is translated to its intended length value by multiplying it by the hyperfine transition of hydrogen value of 21-cm.

8 (in binary) x 21 (cm) = 168 (cm)

The value is intended to represent the average height of women at around 168 cm (or about 5-foot-6 inches)

Solar System Diagram

The bottom diagram represents the Earth’s solar system and is perhaps the most recognizable diagram for any terrestrial travelers. The nine planets (and the Sun) present at the time of the Pioneer’s launch are represented from left to right: the Sun, Mercury, Venus, the weary and familiar sight of Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto.

While each planet’s size and distance between each other is not to scale, they are accompanied by additional binary values that represent their relative distance from the Sun. These binary symbols are different from the binary values used throughout the plaque since they do not use the hydrogen cipher. This difference is indicated by the binary values being displayed as serif letters instead of sans-serif. After it has been translated from binary, the values represent a multiple of 1/10th the semimajor axis of the orbit of Mercury or 0.0387 A.U:

integer value from binary X 0.0387 (AU) = orbital distance from the Sun

These values on the diagram would be difficult to resolve without knowing the orbit of Mercury. However, even if the distances of the solar system’s planet cannot be deciphered by an alien life, the representation of the rings of Saturn should help to distinguish the Earth’s solar system from the remaining thousands of the nearest stars that the pulsars could indicate. In addition, the small schematic of the Pioneer spacecraft indicates which planet in the diagram the craft was launched from as well the path it took around Jupiter and out of the solar system. The antenna is also positioned to point back at Earth to further clarify its point of origin.

With the combination of the 10 visible fingers and toes on each human and the use of the binary value of 10 to represent the orbit of Mercury it is also possible that this could be correctly interpreted as an indication of the Earth’s development of a base-10 counting system

How to Read a Pulsar Map with the Galactic Center

The most prominent and cryptic symbols of the plaque are the radial display on the left. This represents a display of stellar landmarks that give the position and frequency of 14 pulsars relative to the center of the map’s home star, the Earth’s Sun. Pulsars are rotating neutron stars that emit strong directional jets of high energy particles. Since the stream of electromagnetic radiation can only be observed when it is pointed in the direction of the observer, as the star rotates it acts much like a cosmic lighthouse. Pulsars can be identified by their unique and predictable rotational period.

Frank Drake identified the 14 pulsars with short periods of rotation and the greatest longevity and luminosity to make them easy to identify even after long stretches of time to serve as the prominent landmarks. The pulsars are displayed on the plaque as an axial radial map with the Earth’s Sun at the center, connected by 15 solid lines that end in tick marks. Each of the 14 radial lines represent a unique pulsar’s relative distance from the Sun. The 15th line is the longest horizontal line and runs behind the diagrams of the man and woman. This line has no binary representation and represents the galactic plane and the distance the Sun sits from the center of the galaxy. This is a reference line for all the other pulsar’s distances. The length of a pulsar’s line can be compared to the length of the 15th line to gauge their relative distances compared to the distance between the Sun and the center of the galaxy.

If the Pioneer craft is intercepted within the next few tens of millions of years—even after it has travelled hundreds of parsecs—it is likely that all 14 pulsars will still be detectable. Even if they are not all as visible, only a few pulsars are needed to triangulate the Pioneer’s point of origin. In addition, two of the Pulsars (0950 and 1929) are particularly close to the Earth’s sun, allowing the position of the Earth to be approximated to within 1 in 103 stars.

The characteristic frequency of each pulsar is represented in binary along each axial line, however since the hydrogen cipher can represent both a distance and a time, there is no direct indication which is used for the pulsars. However, since the binary values are exceptionally large, they can be assumed to be a time, rather than distance, although a smart traveler (with ample time) could try both.

integer value from binary x 1450 (hz) = Period (in units of hyperfine transition of Hydrogen)

Along the axial spokes, the string of binary numbers represent the unique frequency of the pulsar at the time of the Pioneer launch. Pulsars radiate at a regular frequency emitting electromagnetic radiation at predictable intervals and over time that frequency decreases, allowing the exact period of the pulsar to serve as a timestamp. The pulsars allow an intelligent civilization with historical records of pulsars to determine the time elapsed since the Pioneer was launched, acting as a landmark of time and space.

The tick marks near the end of each axial spoke line represent the z-coordinate relative to the galactic plane. They are also used to determine the distance from the galactic center for each pulsar. The angle between the line representing the galactic plane and the tick mark of a pulsar represents the direction angle from the galactic center.

The distance each pulsar is shown on the pulsar map as a relative distance. The distance for each pulsar is from the center of the map to the tick mark on the line for each pulsar. The length of the 15th line for the galactic plane can be labelled as 100, so that when the length is compared to the distances for each pulsar they lie between 1 and 100.

While the map is a flat two-dimensional object, it can be extrapolated based on the polar coordinates (r, θ) of each pulsar. As a coordinate, r is the distance a pulsar is from the Sun and θ is the angle between the galactic plane and the tick mark on the end of the axial spoke. Pulsars above the horizontal line of the galactic plane are stars found above the Sun’s relative position in the galaxy (+) and those beneath it sit below the Sun along the galactic disc (-)

Human Diagrams

The plaque includes an artistic diagram of two humans to represent the starry-eyed creatures that created and launched the plaque and spacecraft. The figures, a man and a woman, were intended as a universal greeting and representatives of all mankind.

Any meaning from the stances or features of the figures would likely be lost on any alien life, but among humans the man’s upraised hand is considered a universal symbol of goodwill and was included for want of a better symbol. However, it has the additional advantage of clearly displaying the human hand and the opposable thumb. With the ten visible fingers and toes, an optimistic writer could hope that this could potentially be a clue to humanity’s arboreal lineage and base-10 counting system. The woman stands in a different, more relaxed pose than the man, with her body weight shifted to display the flexible and mobile nature of the human body as well as the diversity among different human body types. Originally they were envisioned to be holding hands in a gesture of goodwill, but were eventually decided to be separated to avoid accidentally implying that they are a single organism. Both figures are positioned in front of a large schematic of the Pioneer spacecraft to put them in scale with the spacecraft. Whether or not the Pioneer Plaque will be discovered by alien life or curious and lost chrononauts, the plaque serves as a message to the universe from a time when humanity had first begun to take bold strides into the stars and beyond

Pioneer 10 was sent with an intergalactic return address, but no stamps

We have completed maintenance on Astronomy.com and action may be required on your account. Learn More

- Login/Register

- Solar System

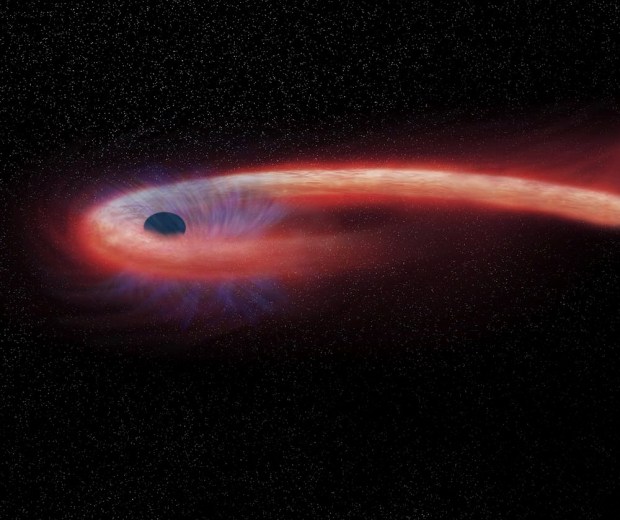

- Exotic Objects

- Upcoming Events

- Deep-Sky Objects

- Observing Basics

- Telescopes and Equipment

- Astrophotography

- Space Exploration

- Human Spaceflight

- Robotic Spaceflight

- The Magazine

Will the messages we sent to the stars be understood?

While we cannot take anything for granted when it comes to how these messages might or might not be interpreted, let’s assume that the beings who might find the spacecraft can at least see or hear with eyes or ears similar to our own. Each message was designed with not only the information it was to carry in mind, but also the means to establish understanding through common denominators found throughout the universe.

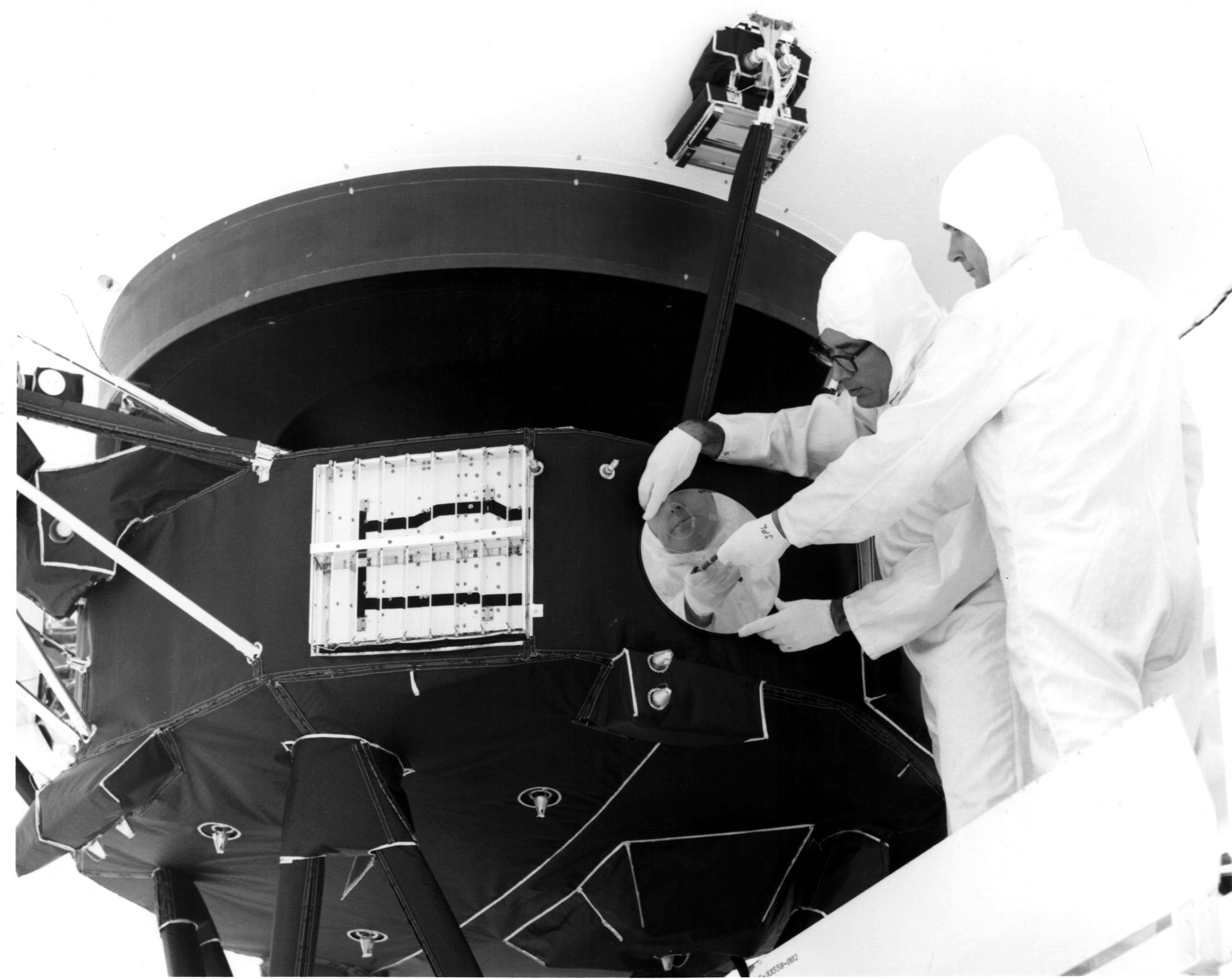

The Pioneer plaque

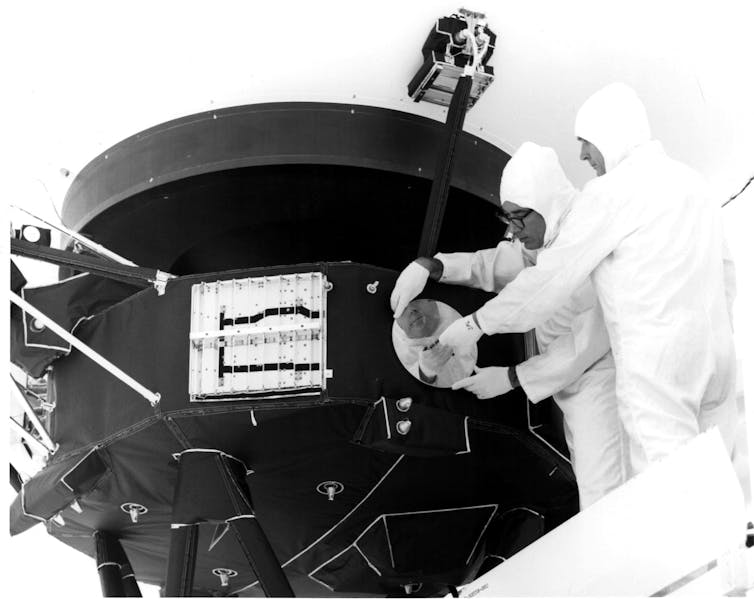

Pioneer 10 and 11 each carry a 6 x 9-inch (15 x 23 centimeters), gold-anodized aluminum plaque. The plaque is affixed to support struts close to the spacecraft’s bus (main body). Carl Sagan and Frank Drake played key roles in designing the plaque and Linda Salzman Sagan, Sagan’s wife at the time, was the artist who actually drew the images engraved on the plaque.

The couple both have a bland expression (which may have been an attempt to avoid anything that could be interpreted as hostile) and the man is seen raising his right hand with the palm facing the viewer. While this gesture clearly conveys a greeting when viewed by another human, an extraterrestrial may have no way of interpreting this gesture. (Could you interpret a gesture made by an antelope … or a praying mantis?) It does show, however, that humans have opposable thumbs, as well as the general range of motion of the upper limbs.

With regards to the scientific data presented, the top left of the plaque shows the hyperfine transition of neutral hydrogen as a means of conveying to the reader baseline units of time (0.7 nanoseconds, the frequency of the transition) and distance (21 cm, the wavelength of the light released by the transition). If one is able to deduce that the image is that of hydrogen, the time and distance should be understandable.

The plaque also contains a map of our Sun relative to 14 pulsars as well as the center of our galaxy, conveying both the distances to the pulsars and their frequency in binary notation. As this image conveys copious objective data, a spacefaring species might well be able to easily interpret it.

Finally, the plaque contains a map of the solar system. The solar system map is likely among the more easily interpreted parts of the plaque, with Pioneer shown to have originated from the third planet. The plaque was created at a time when Pluto was still considered the ninth planet (before the discovery of other trans-Neptunian dwarf planets such as Eris and Sedna, among others), but it would still direct the reader’s attention to Earth if they were able to figure out that our solar system was the one depicted.

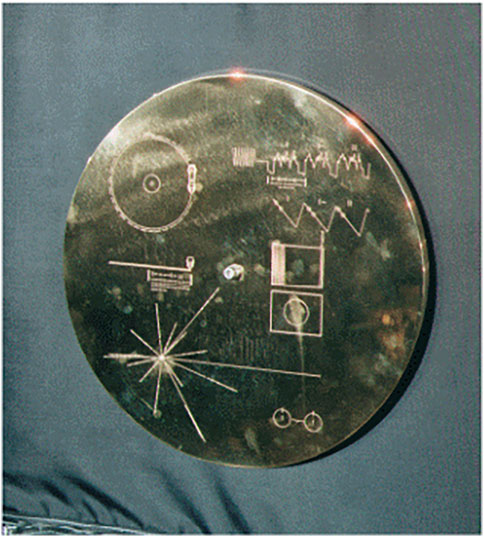

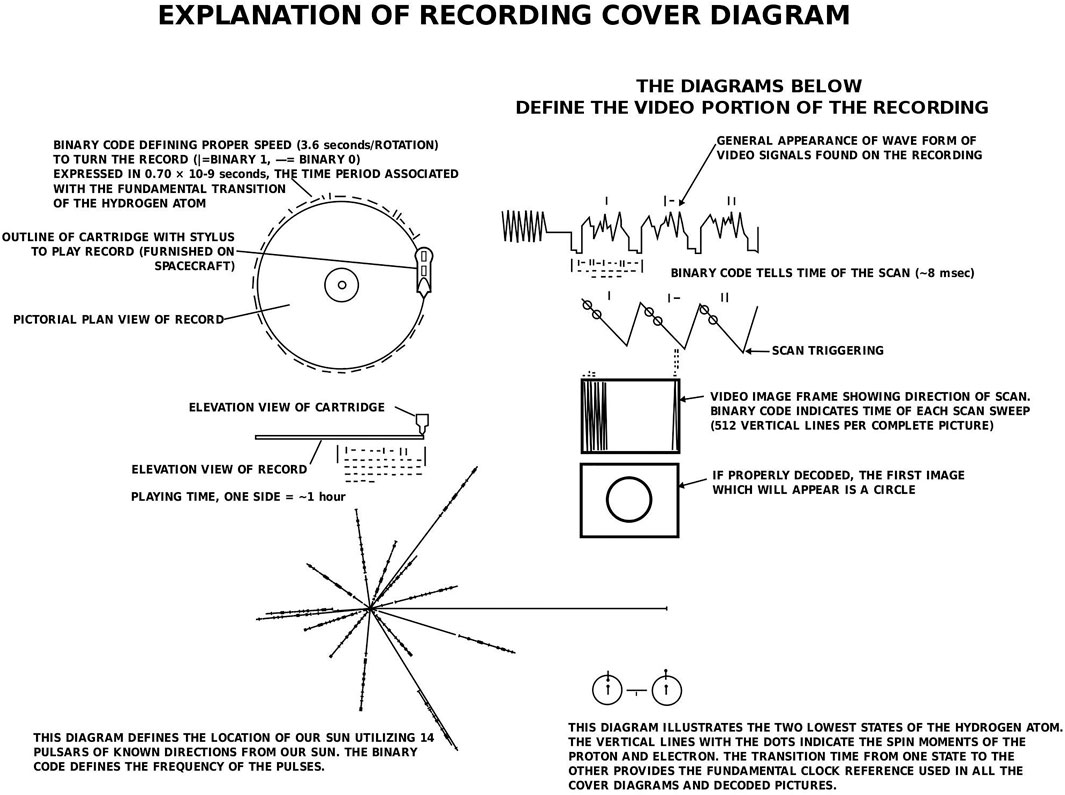

The Voyager record asks more of whoever finds it but gives more information in return. These phonographs, attached to the spacecraft bus, feature a cover illustration and over 90 minutes of audio on the reverse side. The cover illustration features the same image of hydrogen and the same pulsar map as found on the Pioneer plaque. Of critical importance, the Voyager records convey instructions on how to play them, such as how to affix the attached stylus, at what rate of rotation the record must be spun, and the proper waveform of signals generated by the record. It also explicitly tells the reader how to know if they are viewing the images properly via an engraving of what the first image (a circle) should look like. While this may seem very daunting, the challenge is primarily technical and might well be easily overcome by an advanced spacefaring species.

Similarly, the musical selections chosen demonstrate a wide range of human musical styles (ranging from works of Beethoven and Stravinsky to those of Chuck Berry, among others). While the lyrics of “Johnny B. Goode” are probably gibberish to an extraterrestrial, the beat and rhythm of the song would convey a tremendous amount to an alien listener.

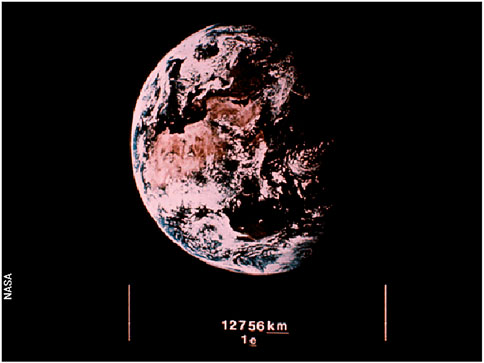

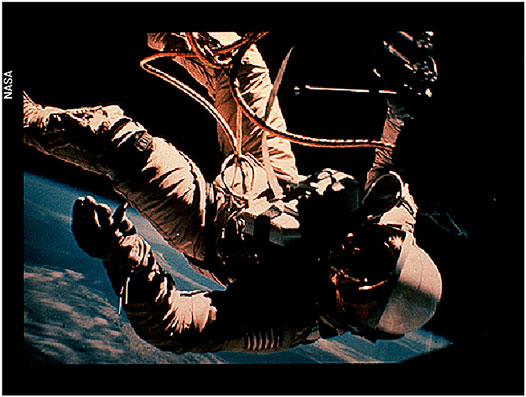

Of perhaps the greatest importance are the 115 images encoded on the record . The first six images, if decoded properly, provide immense technical data for the reader regarding mathematical definitions, scales and sizes, as well as additional information regarding our location and how to find us. Images of the Sun and its spectrum, as well as some of the planets in our solar system, could help the discoverer of the Voyagers to find us should they decide to pay the Earth a visit. There are also approximately 20 medical and scientific diagrams including the structure of DNA and detailed images of human anatomy. These images could likely be interpreted correctly given their concrete nature.

The Voyager record also contains a plethora of images of humans engaged in a variety of activities (including eating, looking through a microscope, and even going on a spacewalk). While many of these images would be hard to interpret (e.g., a picture of a woman licking an ice cream cone or a photo of a string quartet) the images would at least convey that humans have created a complex civilization with some degree of advanced technology.

The Big Picture

As Marshall McLuhan famously said, “The medium is the message.” While the recipients of the Pioneer plaque or the Voyager record might never understand everything we are trying to convey, the fact that these messages were placed on interstellar spacecraft carry (both for them and for us) a deeper message — that humans created these spacecraft and that we want to tell the universe who we are.

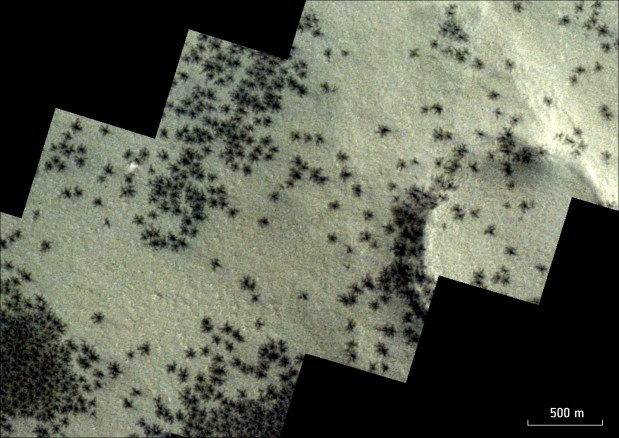

The science behind the ‘spiders’ on Mars and the Inca City

2024 Full Moon calendar: Dates, times, types, and names

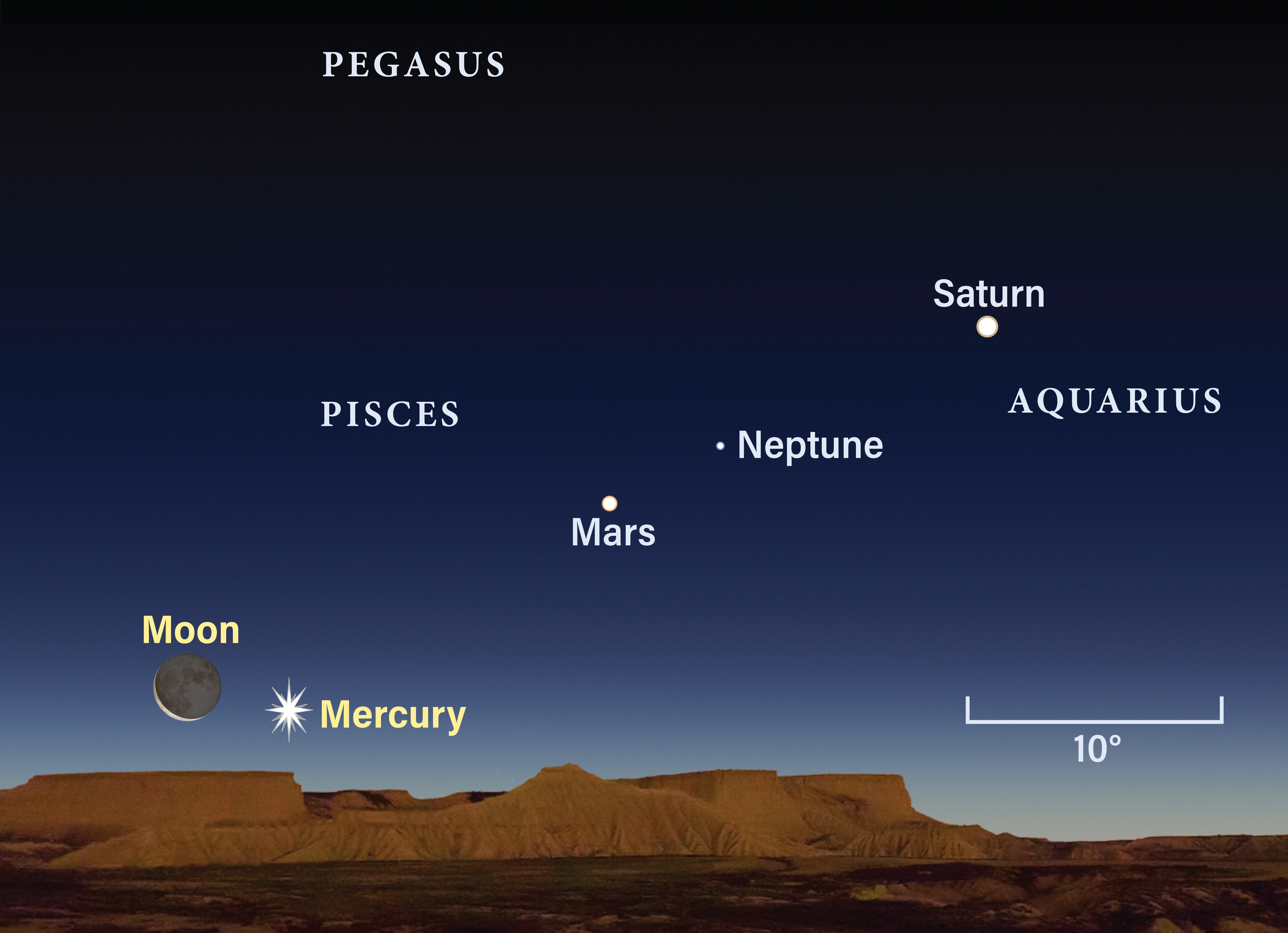

Planets on parade: This Week in Astronomy with Dave Eicher

What happens if someone dies in space?

The Milky Way, to ancient Egyptians, was probably mixed Nuts

The reasons why numbers go on forever

Astronomy Magazine Annual Index

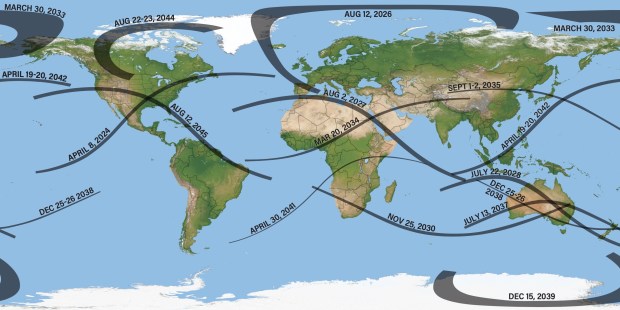

How to see the next 20 years of eclipses, including the eclipse of a lifetime

IceCube researchers detect a rare type of particle sent from powerful astronomical objects

Pioneer 10: Greetings from Earth

Pioneer 10 was a breakthrough mission, accomplishing several firsts among spacecraft. It was the first to fly beyond Mars, the first to fly through the asteroid belt, first to swing by the planet Jupiter, and first to leave the solar system. Along the way, the spacecraft even generated a mystery of its own – the Pioneer Anomaly – that took decades for scientists to solve.

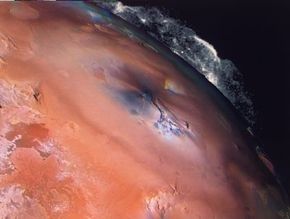

Thanks to Pioneer 10's pictures, the planet Jupiter and its moons , which were formerly only small circles in a telescope, became large, vibrant worlds in the eyes of scientists. For decades after those images beamed back to Earth, Pioneer 10 kept going. It sent valuable scientific data about the sun and cosmic rays before its signal became too faint for Earthlings to hear.

Pioneer 10 also carries a plaque with a message to any intelligent life it might encounter on its journey. The Pioneer plaque includes diagrams of Earth's location and drawings of a man and a woman.

Instruments and art

Launched on March 2, 1972, Pioneer 10 was the latest in a series of missions to explore space, which was still a very new frontier at the time. The earliest Pioneers aimed for the moon, while later generations forged farther and farther into space.

This spacecraft, powered by four radioisotope thermoelectric generators, measured 9.5 feet (2.9 meters) long and weighed 570 pounds (258 kilograms). Among the instruments and camera equipment on board, Pioneer also carried something special: a six- by nine-inch (15.2 by 22.8 centimeters) gold plaque.

The plaque depicts two nude figures – a man and a woman – along with diagrams of the solar system and the sun's position in space. It was intended to serve as a map to Earth for any extraterrestrials who might be curious about who made the spacecraft.

Two people designed the plaque: famed television host and astronomer Carl Sagan , and Frank Drake , founder of SETI and author of an equation that measures the likelihood of communicating with intelligent life.

Imaging Jupiter

Pioneer 10's primary target was the planet Jupiter . It launched from Earth on an Atlas-Centaur three-stage launcher, intended to boost the spacecraft to 32,400 mph (52,142 kph). Sailing away from Earth faster than any spacecraft before it, Pioneer soared by the moon just 11 hours later and made it past Mars in only three months.

Perhaps Pioneer's most dangerous phase was the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, which it reached on July 15. Pioneer faced the risk of colliding with bits of asteroids, anywhere from the size of a small particle to rocks as big as the state of Alaska, according to NASA. But it made it safely to the other side and reached Jupiter on Dec. 3, 1973.

Pioneer 10 was just intended to be a scout for future missions, so its stay at Jupiter was brief. It came within 81,000 miles (130,000 kilometers) of the surface as it sailed past. Pictures beamed back to Earth revealed Jupiter as a liquid giant, while other instruments recorded information on Jupiter's radiation belts and magnetic fields.

The spacecraft also sent back snapshots of some of Jupiter's moons. Although the shots were taken from a distance, scientists could pick out shadows and featureson Europa , Ganymede , Io and Callisto . It was incredible resolution compared to the almost 400 years of observations previously done through telescopes.

On through the outer solar system

Pioneer's story does not end there. For about a quarter-century, the little spacecraft flew farther and farther away from Earth and continued producing science. It measured particles streaming from the sun, and cosmic rays incoming from outside the solar system.

Along with sister ship Pioneer 11, the spacecraft also embroiled scientists in an intergalactic mystery. For decades, NASA was puzzled as to why the two probes travelled 3,000 miles (4,828 km) less than projected, every single year.

Dubbed the "Pioneer Anomaly," it was only in 2012 that NASA found out what happened : heat flowing through the spacecrafts' power systems and instruments was pushing back on the Pioneers as they moved out of the solar system.

NASA concluded Pioneer's science mission on March 31, 1997, but kept track of the spacecraft through the Deep Space Network . Obtaining its signal was used as training for flight controllers looking to get data from the Lunar Prospector mission, which flew for 19 months before being deliberately crashed into the moon's surface in 1999 .

Pioneer 10 last sent data back to Earth on April 27, 2002. Its decaying signals were just too faint for NASA's antennas to pick up anymore.

As far as we know, the spacecraft sails on. NASA warmly refers to Pioneer 10 as a " ghost ship " of the outer solar system as the spacecraft coasts in the general direction of Aldebaran – the eye of the bull in the constellation Taurus.

Residents of that region of space will need to be patient if they want to see Pioneer 10. NASA expects it will take the spacecraft 2 million years to traverse the 68 light-years of space to Aldebaran.

— Elizabeth Howell, SPACE.com Contributor

- Jupiter, Largest Planet of the Solar System

- Carl Sagan: Cosmos, Pale Blue Dot & Famous Quotes

- NASA's 10 Greatest Science Missions

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, " Why Am I Taller ?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace

Mars exploration, new rockets and more: Interview with ESA chief Josef Aschbacher

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video)

Hubble Space Telescope pauses science due to gyroscope issue

Most Popular

- 2 'Cat nights' are here as Leo, Leo minor, and Lynx constellations prowl the evening sky

- 3 Highly precise atomic clocks could soon get even better. Here's how

- 4 Mars exploration, new rockets and more: Interview with ESA chief Josef Aschbacher

- 5 Everything we know about James Gunn's Superman

Voyager Golden Records 40 years later: Real audience was always here on Earth

Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Penn State

Disclosure statement

Jason Wright acknowledges funding from NASA, the NSF, the Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Words at The Pennsylvania State University, and from Breakthrough Listen, part of the Breakthrough Initiatives sponsored by the Breakthrough Prize Foundation ( https://breakthroughinitiatives.org/ ).

Penn State provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

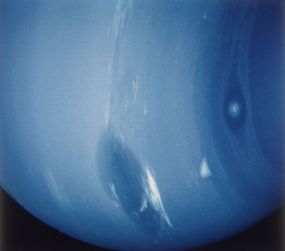

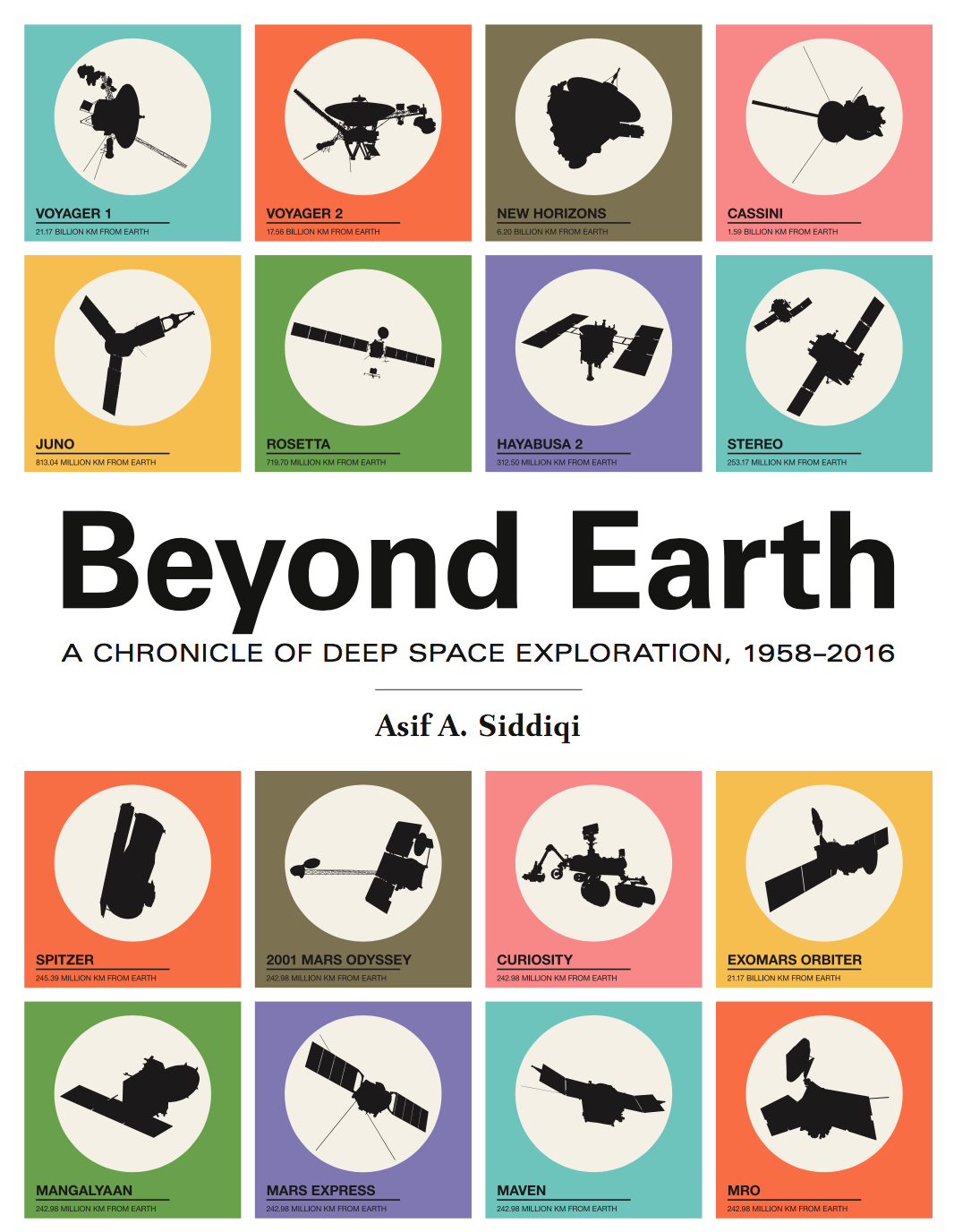

Forty years ago, NASA launched Voyager I and II to explore the outer solar system. The twin spacecraft both visited Jupiter and Saturn; from there Voyager I explored the hazy moon Titan, while Voyager II became the first (and, to date, only) probe to explore Uranus and Neptune. Since they move too quickly and have too little propellant to stop themselves, both spacecraft are now on what NASA calls their Interstellar Mission , exploring the space between the stars as they head out into the galaxy.

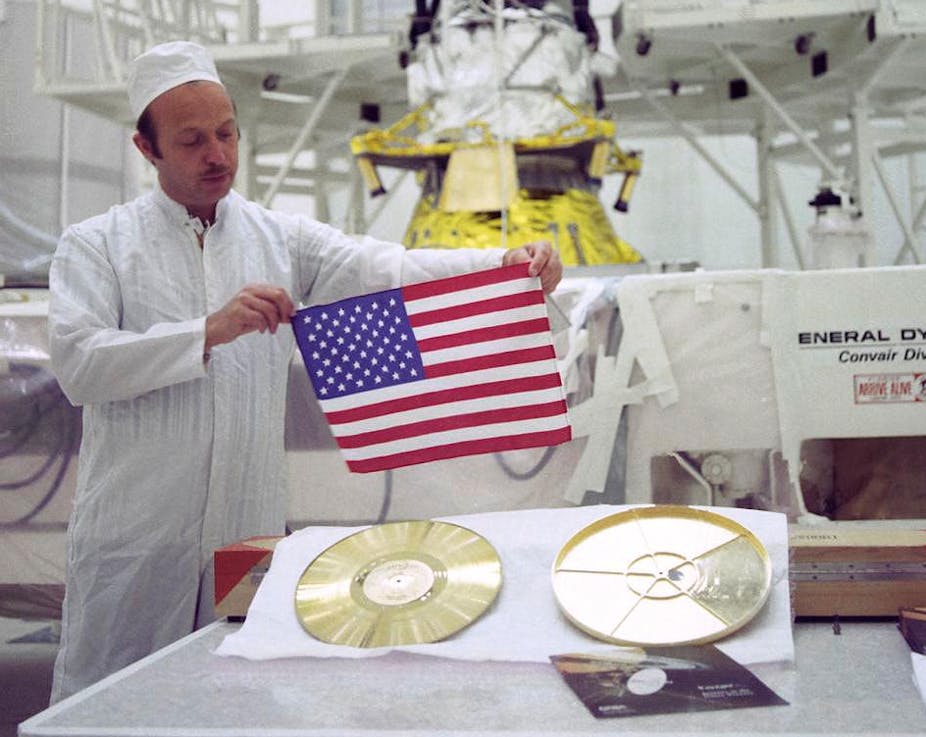

Both craft carry Golden Records : 12-inch phonographic gold-plated copper records, along with needles and cartridges, all designed to last indefinitely in interstellar space. Inscribed on the records’ covers are instructions for their use and a sort of “map” designed to describe the Earth’s location in the galaxy in a way that extraterrestrials might understand.

The grooves of the records record both ordinary audio and 115 encoded images . A team led by astronomer Carl Sagan selected the contents, chosen to embody a message representative of all of humanity. They settled on elements such as audio greetings in 55 languages , the brain waves of “a young woman in love” (actually the project’s creative director Ann Druyan, days after falling in love with Carl Sagan ), a wide-ranging selection of musical excerpts from Blind Willie Johnson to honkyoku , technical drawings and images of people from around the world, including Saan Hunters, city traffic and a nursing mother and child.

Since we still have not detected any alien life, we cannot know to what degree the records would be properly interpreted. Researchers still debate what forms such messages should take . For instance, should they include a star map identifying Earth? Should we focus on ourselves, or all life on Earth? Should we present ourselves as we are, or as comics artist Jack Kirby would have had it, as “the exuberant, self-confident super visions with which we’ve clothed ourselves since time immemorial”?

But the records serve a broader purpose than spreading the word that we’re here on our blue marble. After all, given the vast distances between the stars, it’s not realistic to expect an answer to these messages within many human lifetimes. So why send them and does their content even matter? Referring to earlier, similar efforts with the Pioneer spacecraft , Carl Sagan wrote , “the greater significance of the Pioneer 10 plaque is not as a message to out there; it is as a message to back here.” The real audience of these kinds of messages is not ET, but humanity.

In this light, 40 years’ hindsight shows the experiment to be quite a success, as they continue to inspire research and reflection.

Only two years after the launch of these messages to the stars, “Star Trek: The Motion Picture” imagined the success of similar efforts by (the fictional) Voyager VI. Since then, there have been Ph.D. theses written on the records’ content , investigations into the identity of the person heard laughing and successful crowdfunded efforts to reissue the records themselves for home playback.

The choice to include music has inspired introspection on the nature of music as a human endeavor, and what it would (or even could) mean to an alien species. If an ET even has ears, it’s still far from clear whether it would or could appreciate rhythm, tones, vocal inflection, verbal language or even art of any kind. As music scholars Nelson and Polansky put it , “By imagining an Other listening, we reflect back upon ourselves, and open our selves and cultures to new musics and understandings, other possibilities, different worlds.”

The records also represent humanity’s deliberate effort to put artifacts among the stars. Unlike everything on Earth, which is subject to erosion and all but inevitable destruction (from the sun’s eventual demise, if nothing else), the Golden Records are essentially eternal, a permanent time capsule of humanity. And unlike the Voyager spacecraft themselves – which were designed to have finite lifespans and whose journey into interstellar space was incidental to their primary function of exploring the outer planets – the Golden Records’ only purpose is to serve as ambassadors of humanity to the stars.

Placing artifacts in interstellar space thus makes the galaxy subject to the social studies, in addition to astronomy. The Golden Records mark our claim to interstellar space as part of our cultural landscape and heritage , and once the Voyager spacecraft themselves are not functional any longer, they will become proper achaeological objects . They are, in a sense, how we as a species have planted our flag of exploration in space. Anthropologist Michael Oman-Reagan muses , “Has NASA been to interstellar space because this spacecraft has? Have we, as a human species, [now] been to interstellar space?”

I would argue we have, and we are a better species for it. Like the Pioneer plaques and the Arecibo Message before them, the Golden Records inspire us to broaden our minds about what it means to be human; what we value as humans; and about our place and role in the cosmos by having us imagine what we might, or might not, have in common with any alien species our Voyagers eventually encounter on their very long journeys.

- Extraterrestrial life

- Space exploration

- Golden Record

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Nutrition Research Coordinator – Bone Health Program

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Advertisement

How Voyager Works

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

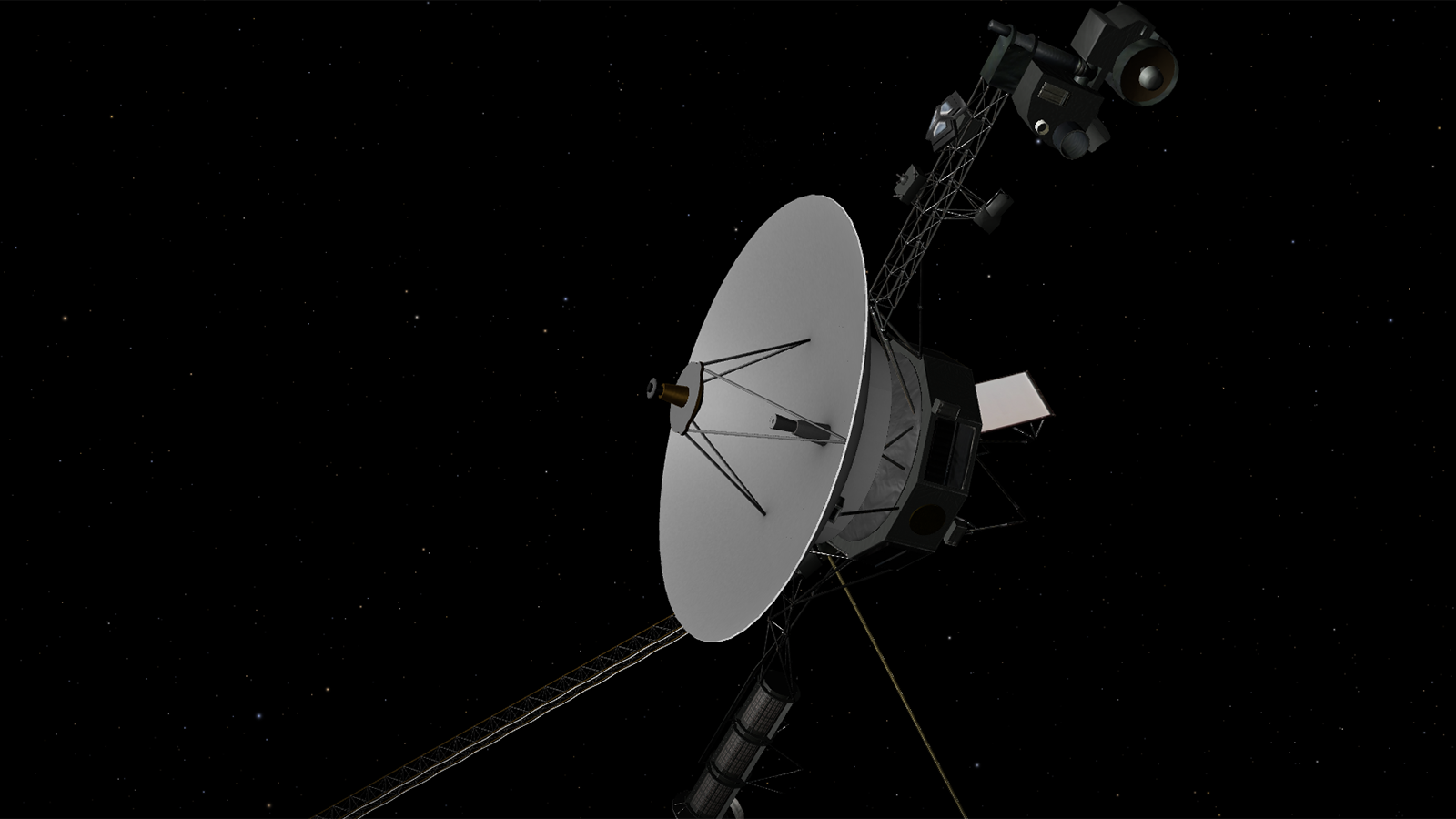

At this moment, two spacecraft that were launched from Earth in 1977 hurtle through space at more than 30,000 mph (48,280 km/h). They are both several billion miles away, farther from Earth than any other man-made object. On Aug. 25, 2012, one of them crossed into interstellar space, making the first spacecraft to leave the solar system

Voyager 1 and 2 carry coded messages to potential alien civilizations. They have already taught scientists a great deal about the heliosheath , the outermost layer of the solar system. But none of this is even what they were designed for.

The Voyager spacecrafts were built to fly past the outer planets ( Jupiter , Saturn , Neptune and Uranus ) and study them closely, the first time in human history they'd been observed up close. The spacecraft succeeded magnificently, advancing planetary science by vast leaps. It was only after they’d accomplished their primary mission that they continued on to become Earth’s most far-ranging explorers.

Yet it was a matter of extremely good luck and timing that the missions were possible at all -- and an equal stroke of bad luck that almost scuttled the Voyager project before it ever left the ground. These ambitious missions were the product of new advances in the science and math of orbital trajectories, but they were almost cast by the wayside in favor of the expensive space shuttle program. Virtually every unmanned space mission undertaken today relies on knowledge and experience gained by the Voyagers.

We’ll take a close look at the ungainly Voyager space probes and all the technical equipment they carry on board. We’ll trace their trajectory from the development stages to their ultimate fate light years away from Earth. There will be stops at the largest planets in our solar system along the way. And if you’re wondering what's on the golden records each Voyager carries as messages for alien life forms, we’ll give them a spin. Will any aliens ever find them?

Voyager 1 and 2: The Grand Tour

Voyager equipment, to neptune and beyond, voyager golden record.

The 1970s were a transitional period for the U.S. space effort. The Apollo program was coming to a close, and NASA was trying to figure out what form manned spaceflight would take. The Mariner missions expanded our knowledge of the inner planets by sending space probes to fly past (and in some cases orbit) Mars , Venus and Mercury . There were tentative plans to send a Mariner mission to visit some of the outer planets, but using chemical rocket propulsion, such a trip would take 15 years or more.

At the same time, important advances were being made in the science of gravity-assisted orbital trajectories . While the math and physics involved are pretty complicated, the basic idea is that a spacecraft can use the gravity of a nearby planet to give it a large boost in velocity as long as the spacecraft follows the proper orbit. The higher the mass of the planet, the stronger the gravitational force, and the bigger the boost. That meant that once a space probe reached Jupiter (the most massive planet in our solar system ), it could use Jupiter’s gravity like a slingshot and head out to explore the more distant planets.

In 1965, an engineer named Gary Flandro noticed that in the mid-1970s, the outer planets would be aligned in such a way as to make it possible for a spacecraft to visit them all using a series of gravity-assisted boosts [source: Evans ]. This particular alignment wasn't just a once-in-a-lifetime event -- it wouldn't occur again for another 176 years. It was an amazing coincidence that the technical ability to accomplish such a mission was developed a few years before the planets lined up to allow it.

Initially, the ambitious project, known as the Grand Tour, would have sent a series of probes to visit all the outer planets. In 1972, however, budget projections for the project were approaching $900 million, and NASA was planning development of the space shuttle [source: Evans ]. With the immense shuttle development costs looming, the Grand Tour was cancelled and replaced with a more modest mission profile. This would be an extension of the Mariner program, referred to as the Mariner Jupiter-Saturn mission (MJS) . Based on the Mariner platform and improved with knowledge gained from Pioneer 10’s 1973 fly-by of Jupiter, the new probes eventually took the name Voyager. Design was completed in 1977. Optimistic NASA engineers thought they might be able to use gravity-assisted trajectories to reach Uranus and Neptune if the initial mission to visit Jupiter and Saturn (and some of their moons) was completed successfully. The idea of the Grand Tour flickered back to life.

The final Voyager mission plan looked like this: Two spacecraft (Voyager 1 and Voyager 2) would be launched a few weeks apart. Voyager 1 would fly past Jupiter and several of Jupiter’s moons from a relatively close distance, scanning and taking photos. Voyager 2 would also fly past Jupiter, but at a more conservative distance. If all went well, both probes would be catapulted toward Saturn by Jupiter’s gravity. Voyager 1 would then investigate Saturn, specifically the rings, as well as the moon Titan. At that point, Voyager 1’s trajectory would take it out of the solar system’s ecliptic (the plane of the planets’ orbits), away from all other planets, and eventually out of the solar system itself.

Meanwhile, Voyager 2 would visit Saturn and several of Saturn’s moons. If it was still functioning properly when that was completed, it would be boosted by Saturn’s gravity to visit Uranus and Neptune before also leaving the ecliptic and exiting the solar system. This was considered a long shot, but amazingly, everything worked as planned.

Next, what kind of hardware did the Voyagers carry into space?

Voyager 2 launched from Cape Canaveral, Fla., on board a Titan-Centaur rocket on Aug. 20, 1977. Voyager 1 launched on Sept. 5, 1977. Why is the numbering reversed? Once en route to the outer planets, Voyager 1 passed by Voyager 2 and reached Jupiter first. NASA thought the public would be confused if Voyager 2 started reporting back first, so the numbering doesn't follow the launch order.

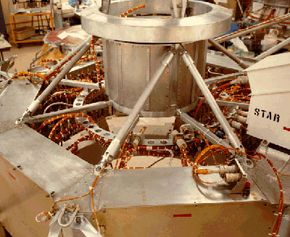

Both Voyager spacecraft are identical. They don't have a sleek, aerodynamic design because there's no aerodynamic friction in space to worry about. Weighing 1,592 pounds (722 kilograms), they're made up of a main bus, a high-gain antenna, three booms that held scientific instruments and the power supply, and two other antennae.

The main bus is the body of the Voyager. It's a 10-sided box 5.9 feet (1.8 meters) across, and it contains some scientific instruments, electronics and a fuel tank for the rocket thrusters. The thrusters are used to reorient the craft as it moves through space.

Mounted on top of the main bus, the high-gain antenna is 12 feet (3.7 meters) across and looks like a satellite dish. This antenna is how the Voyagers receive commands from Earth and send the data they gather back. No matter where a Voyager spacecraft flies, the high-gain antenna always points toward Earth.

One of the booms extending off of the main bus carries Voyager’s radioisotope thermoelectric power supply . Pellets of plutonium dioxide release heat through natural decay. This heat is converted into electricity using a series of thermocouples. Although the power output isn't very strong, it powers the electronics and instruments on board the Voyagers for a very long time. Power isn't expected to deplete completely until 2020. The power supply was placed on a boom to keep the radiation from interfering with the other scientific instruments.

The other two booms carry a series of instruments. These include:

- Magnetometer

- Cosmic ray detector

- Plasma detector

- Photopolarimeter

- Infrared interferometer

- Spectrometer

- Ultraviolet spectrometer

- Low energy charged particle detector

- Plasma wave detector

[source: Evans, Dethloff & Schorn ]

Perhaps the most significant instruments on board the Voyagers, as far as the public is concerned, are the cameras. Also mounted on the instrument boom, the cameras have a resolution of 800x800, with both wide-angle and narrow-field versions. The cameras returned unprecedented photos of the outer planets and gave us views of our solar system that we had never before witnessed (including the famous departure shot showing both Earth and Earth’s moon in the same frame). The boom carrying the cameras could be moved independently from the rest of the craft.

The Voyager’s computer system was very impressive as well. Knowing the craft would be on its own much of the time, with the lag between command and response from Earth growing longer the farther the craft went into space, engineers developed a self-repairing computer system . The computer has multiple modules that compare the data they receive and the output instructions they decide on. If one module differs from the others, it's assumed to be faulty and is eliminated from the system, replaced by one of the backup modules. It was tested shortly after launch, when a delay in boom deployment was misread as a malfunction. The problem was corrected successfully.

In the next section, we’ll find out what we learned from the Voyager missions.

While the Voyagers themselves did all the data gathering, there were important mission elements on the ground as well. The Voyagers’ signals became increasingly difficult to detect as they flew out into the outer solar system, so NASA improved a worldwide network of radio receiving stations to better detect them. A series of 230-foot (70-meter) radio dishes pull in the Voyager data and send signals out to it, maintaining almost continuous communication [source: Evans ].

Although the lifetime mission cost for Voyager exceeded $750 million, by 1989 the spacecrafts had returned enough scientific data to fill 6,000 editions of the Encyclopedia Britannica [source: Evans ]. The science modules on board were chosen from proposals submitted by research teams across the United States. The information about Jupiter , Saturn , Uranus and Neptune (and many of their moons) that we learned from the Voyager missions wasn't just vast in quantity, but also in influence. It shaped science textbooks in schools across the U.S., informed public perceptions of the solar system and laid the foundation for the modern space program. Much of what we know about the outer planets came from Voyager. That’s not to mention the thousands of photographs taken from vantage points humans had never experienced before. Those brilliant images of Jupiter and Saturn fired the public’s imagination and fueled enthusiasm for future space exploration.

From Voyager, we learned more about the weather on Jupiter; the rings around Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus; volcanic activity on Jupiter's moon Io; the masses and densities of Saturn’s moons; the atmospheric pressure on Titan, Saturn's largest moon; the magnetic field of Uranus; and a persistent weather system on Neptune as large as Earth , known as the Great Dark Spot . By the time Voyager 2 reached Neptune, it was 1989. More than 10 years had passed since launch, and many of the scientists working on the original mission had moved on. Voyager had passed by Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus in 1979, 1981 and 1986, respectively.

So where are they now? The two Voyagers aren't together. Voyager 1 is moving north (relative to the orientation of Earth out of the solar system), while Voyager 2 is moving south. In 2007, they both entered the heliosheath, the outermost section of the solar system. There, the solar wind meets interstellar magnetic fields and forms a boundary with a shock wave. The Voyagers traversed the shock wave and sent data back, giving astronomers their first idea of the shape and location of the heliosheath. On Sept. 21, 2013, Voyager scientists reported that Voyager 1 left the solar system on Aug. 25, 2012.

Although some instruments on the Voyagers are no longer working, they do continue to send back important information. Imagine a car that has been on the road continuously since 1977, and you'll get some idea of how amazing these spacecraft are. At their current distance, it takes radio signals traveling at the speed of light more than 14 hours to reach Earth. The craft are running low on fuel for their orienting thrusters and will have to power down some instruments in the coming years as their plutonium runs out as well. By 2020, they will be dark and silent.

Yet they will continue on their current trajectory, moving over 30,000 mph (48,280 km/h), arcing out into the Milky Way for tens of thousands of years. With no atmosphere in space, they will never corrode, and there is little for them to crash into in interstellar space. It will take them about 40,000 years before they even come within light years of another star . The Voyagers may be traveling for hundreds of thousands or even millions of years.

What if the Voyagers meet an intelligent alien civilization some day? We’ve left a message for them.

When NASA realized that the Voyagers would eventually travel beyond the edge of our solar system , they decided it might be a good idea to include some kind of message to any intelligent aliens who might some day find them. A committee headed by astronomer Carl Sagan put these messages together. They're contained on gold-plated copper discs, which are engraved much like a vinyl record album. A portion of the disc contains audio information, including a variety of music, greetings spoken in 55 different languages (including some that are very obscure or long extinct) and a selection of nature sounds. The discs also include 122 images, encoded as vibrations on the disc with instructions for decoding.

On each disc’s cover plate are several symbols that depict the method of playing back the record (a stylus and mounting platter are included as well). The image decoding instructions are revealed, describing the “image start” signal, the aspect ratio of the images, and a reproduction of the first image, so the aliens would know if they got it right. A star map clearly showing the location of Earth completes the picture.

If the aliens wonder how long the Voyager they find has been traveling, they can examine the piece of uranium-238 attached to the main bus near the record. Examining the isotope ratios (assuming they know the half-life of uranium-238), they could then deduce how long the sample had been in space.

What music will the aliens hear when they play the record? Mostly traditional music from a variety of cultures, such as Native Americans chants, Scottish bagpipes and African ritual music. It is also something of a “greatest hits” collection of classical music. The most contemporary songs are “Johnny B. Goode” by Chuck Berry and a jazz number by Louis Armstrong.

The images on the record are varied, and include maps of Earth, images of the other planets in our solar system, pictures of various animals and several images of humans. Carl Sagan wrote a book about the record, called "Murmurs of Earth." A companion CD-ROM was released decades later.

The Voyager discs are similar to a plaque that was placed aboard Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11, although the creators of the Voyager discs spent a lot of time making sure the aliens could decode it. Many Earth scientists could not decode the information on the Pioneer plaque. At the time, some voiced concerns that any hostile aliens finding the Voyager disc would have a map leading them directly to Earth. However, the Voyagers will spend tens of thousands of years in interstellar space before they are anywhere near another star, so the matter isn’t really an immediate concern. If the discs are ever found, it may be so far in the future that humans no longer exist.

For more interesting articles about space exploration, try the next page.

In "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" (the first Star Trek film), much of the plot revolved around a strange electronic life form known as V’Ger. By the end of the film, it is revealed that V’Ger is one of the Voyager space probes (Voyager 6, which never existed in the real world) that has either gained sentience on its own or been given sentience by an alien race. It wants to eradicate all of humanity, but instead evolves into yet another form of life.

Within the fictional Star Trek universe, there is some dispute as to V’Ger’s place in Trek history. Some suggest that V’Ger created the Borg, a cold, logical alien race that would become the primary villains in "Star Trek: The Next Generation." Others think the Borg encountered V’Ger, but that the cyborg aliens existed before the chance meeting.

Voyager Space FAQ

What is the temperature of interstellar space, how far away is voyager 2, how far away is voyager 1, do the voyagers have a camera, what is the difference between voyager 1 and 2, lots more information, related articles.

- Are we not the only Earth out there?

- How Lunar Landings Work

- NASA's 10 Greatest Achievements

- How do spacecraft re-enter the Earth?

- How Fixing the Hubble Spacecraft Works

- How Project Mercury Worked

- How Spaceports Will Work

- How Aliens Work

More Great Links

- Voyager Web site

- Evans, Ben. "NASA's Voyager Missions: Exploring the Outer Solar System and Beyond." Springer; 1st ed 2004. 2nd printing edition (April 15, 2008).

- Dethloff, Henry C & Schorn, Ronald A. "Voyager's Grand Tour: To the Outer Planets and Beyond." Smithsonian (March 17, 2003).

- NASA. “Voyager 2 Proves Solar System Is Squashed.” http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

The National Air and Space Museum's full-scale mockup of the Pioneer 10 spacecraft was recently moved to its new location in the Boeing Milestones of Flight Hall as a part of a major renovation to the gallery. The spacecraft includes power supplies, a large dish antenna, and several science instruments used during encounters with the outer planets of the solar system. It also contains something that might sound more like science fiction: A note to any alien civilization that might come across the spacecraft in the distant future.

A replica of the Pioneer 10 spacecraft on display in the Boeing Milestones of Flight Hall at the Museum in Washington, DC.

Pioneer 10 and 11 were the first spacecraft designed to visit the outer solar system—the region beyond Mars. Designed as identical spacecraft, Pioneer 10 was launched on March 2, 1972, and Pioneer 11 on April 6, 1973. Both traversed the asteroid belt and visited Jupiter, while Pioneer 11 also visited Saturn on its way out of the solar system. Pioneer 10 and 11 returned data until 2002 and 1995, respectively, until their power supplies became too weak to support operations. Pioneer 10 and 11, although no longer functioning, are leaving the solar system at 2.6 and 2.5 AU per year, respectively. One AU is the mean distance from the Earth to the Sun, or approximately 150 million km (93 million miles). During planning stages of the Pioneer 10 and 11 missions, science writer Eric Burgess suggested adding a greeting to an alien civilization. The mission team eventually decided to add a small plaque with the message. The plaques were designed by Carl Sagan and Frank Drake and drawn by Sagan's wife at the time, Linda Salzman Sagan. The gold-covered aluminum plaques were affixed to the antenna supports of the two spacecraft. They faced inward for protection from possible erosion caused by micrometeorite strikes. In the mockup on display in the Museum, the artwork faces outward. In Pioneer's new location in the Museum, visitors can get a view of the plaque from the balcony near the Albert Einstein Planetarium box office on the second floor. Look between the large dish antenna and the main part of the spacecraft closer to the wall. The rectangular plaque, about 23 x 15 centimeters (9 x 6 inches), can be seen behind the dish facing the floor away from the National Mall. You can also catch a glimpse standing on the first floor near the bottom of the escalators in front of the Museum store.

Deciphering the Pioneer Plaque The Pioneer plaque contains drawings of two humans and our place in the galaxy. The spacecraft is drawn behind a human male and female for scale. The solar system appears along the lower edge. Each planet and Pluto is shown with a binary number indicating the average distance from the Sun. Distances are listed in units of 1/10th the Mercury distance. The diagram in the upper left shows atomic hydrogen, by far the most abundant element in the universe. It shows a hydrogen atom undergoing a shift in its electron energy level. This change emits electromagnetic radiation at a wavelength of 21 centimeters (8 inches), and is the most common such emission in the universe. This is used as a frequency and distance scale represented by the binary number 1. Converging lines in the left show the position of the Sun relative to 14 pulsars in the Milky Way and the center of the galaxy. Pulsars are very dense remnants of exploded giant stars, and they rotate at very stable frequencies. The frequency of each pulsar is listed in binary numerals relative to the frequency of hydrogen emission. The average human height, of approximately 168 centimeters (or 5 feet 6 inches), is listed on the right-hand side as the binary number 8 (1000, shown as | - - - ), relative to the 21 centimeter (8 inch) wavelength of hydrogen emission. Leaving the Solar System Besides Pioneer 10 and 11, three other spacecraft have reached the Sun's escape velocity and are currently moving out into the stars: Voyager 1, Voyager 2, and New Horizons . The two Voyagers visited the gas giant planets of our solar system. A version of the Pioneer plaque also appears on a gold-covered phonograph record on each of the Voyager spacecraft. Although the Voyager spacecraft were launched five years after the Pioneers, they are traveling faster, and currently the Voyager 1 spacecraft is the most distant form the Earth. New Horizons just flew by Pluto and will continue through the Kuiper Belt. New Horizons contains several objects including a sample of the ashes of Clyde Tombaugh, the discoverer of Pluto . However, it does not carry any material intended to greet alien civilization.

It is very unlikely that the Pioneers or any of the other spacecraft will ever been seen by any alien civilization, even very far into future. Despite this, four of the outgoing spacecraft contain messages. We can see them more as messages to ourselves, not to aliens. They remind us that in the mid-20 th Century A.D., human beings took the first steps toward exploring the universe.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

- Get Involved

- Host an Event

Thank you. You have successfully signed up for our newsletter.

Error message, sorry, there was a problem. please ensure your details are valid and try again..

- Free Timed-Entry Passes Required

- Terms of Use

The most distant human-made object

No spacecraft has gone farther than NASA's Voyager 1. Launched in 1977 to fly by Jupiter and Saturn, Voyager 1 crossed into interstellar space in August 2012 and continues to collect data.

Mission Type

What is Voyager 1?

Voyager 1 has been exploring our solar system for more than 45 years. The probe is now in interstellar space, the region outside the heliopause, or the bubble of energetic particles and magnetic fields from the Sun.

- Voyager 1 was the first spacecraft to cross the heliosphere, the boundary where the influences outside our solar system are stronger than those from our Sun.

- Voyager 1 is the first human-made object to venture into interstellar space.

- Voyager 1 discovered a thin ring around Jupiter and two new Jovian moons: Thebe and Metis.

- At Saturn, Voyager 1 found five new moons and a new ring called the G-ring.

In Depth: Voyager 1

Voyager 1 was launched after Voyager 2, but because of a faster route, it exited the asteroid belt earlier than its twin, having overtaken Voyager 2 on Dec. 15, 1977.

Voyager 1 at Jupiter

Voyager 1 began its Jovian imaging mission in April 1978 at a range of 165 million miles (265 million km) from the planet. Images sent back by January the following year indicated that Jupiter’s atmosphere was more turbulent than during the Pioneer flybys in 1973–1974.

Beginning on January 30, Voyager 1 took a picture every 96 seconds for a span of 100 hours to generate a color timelapse movie to depict 10 rotations of Jupiter. On Feb. 10, 1979, the spacecraft crossed into the Jovian moon system and by early March, it had already discovered a thin (less than 30 kilometers thick) ring circling Jupiter.

Voyager 1’s closest encounter with Jupiter was at 12:05 UT on March 5, 1979 at a range of about 174,000 miles (280,000 km). It encountered several of Jupiter’s Moons, including Amalthea, Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, returning spectacular photos of their terrain, opening up completely new worlds for planetary scientists.

The most interesting find was on Io, where images showed a bizarre yellow, orange, and brown world with at least eight active volcanoes spewing material into space, making it one of the most (if not the most) geologically active planetary body in the solar system. The presence of active volcanoes suggested that the sulfur and oxygen in Jovian space may be a result of the volcanic plumes from Io which are rich in sulfur dioxide. The spacecraft also discovered two new moons, Thebe and Metis.

Voyager 1 at Saturn

Following the Jupiter encounter, Voyager 1 completed an initial course correction on April 9, 1979 in preparation for its meeting with Saturn. A second correction on Oct. 10, 1979 ensured that the spacecraft would not hit Saturn’s moon Titan.

Its flyby of the Saturn system in November 1979 was as spectacular as its previous encounter. Voyager 1 found five new moons, a ring system consisting of thousands of bands, wedge-shaped transient clouds of tiny particles in the B ring that scientists called “spokes,” a new ring (the “G-ring”), and “shepherding” satellites on either side of the F-ring—satellites that keep the rings well-defined.

During its flyby, the spacecraft photographed Saturn’s moons Titan, Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, and Rhea. Based on incoming data, all the moons appeared to be composed largely of water ice. Perhaps the most interesting target was Titan, which Voyager 1 passed at 05:41 UT on November 12 at a range of 2,500 miles (4,000 km). Images showed a thick atmosphere that completely hid the surface. The spacecraft found that the moon’s atmosphere was composed of 90% nitrogen. Pressure ad temperature at the surface was 1.6 atmospheres and 356 °F (–180°C), respectively.

Atmospheric data suggested that Titan might be the first body in the solar system (apart from Earth) where liquid might exist on the surface. In addition, the presence of nitrogen, methane, and more complex hydrocarbons indicated that prebiotic chemical reactions might be possible on Titan.

Voyager 1’s closest approach to Saturn was at 23:46 UT on 12 Nov. 12, 1980 at a range of 78,000 miles(126,000 km).

Voyager 1’s ‘Family Portrait’ Image

Following the encounter with Saturn, Voyager 1 headed on a trajectory escaping the solar system at a speed of about 3.5 AU per year, 35° out of the ecliptic plane to the north, in the general direction of the Sun’s motion relative to nearby stars. Because of the specific requirements for the Titan flyby, the spacecraft was not directed to Uranus and Neptune.

The final images taken by the Voyagers comprised a mosaic of 64 images taken by Voyager 1 on Feb. 14, 1990 at a distance of 40 AU of the Sun and all the planets of the solar system (although Mercury and Mars did not appear, the former because it was too close to the Sun and the latter because Mars was on the same side of the Sun as Voyager 1 so only its dark side faced the cameras).

This was the so-called “pale blue dot” image made famous by Cornell University professor and Voyager science team member Carl Sagan (1934-1996). These were the last of a total of 67,000 images taken by the two spacecraft.

Voyager 1’s Interstellar Mission

All the planetary encounters finally over in 1989, the missions of Voyager 1 and 2 were declared part of the Voyager Interstellar Mission (VIM), which officially began on Jan. 1, 1990.

The goal was to extend NASA’s exploration of the solar system beyond the neighborhood of the outer planets to the outer limits of the Sun’s sphere of influence, and “possibly beyond.” Specific goals include collecting data on the transition between the heliosphere, the region of space dominated by the Sun’s magnetic field and solar field, and the interstellar medium.

On Feb. 17, 1998, Voyager 1 became the most distant human-made object in existence when, at a distance of 69.4 AU from the Sun when it “overtook” Pioneer 10.

On Dec. 16, 2004, Voyager scientists announced that Voyager 1 had reported high values for the intensity for the magnetic field at a distance of 94 AU, indicating that it had reached the termination shock and had now entered the heliosheath.

The spacecraft finally exited the heliosphere and began measuring the interstellar environment on Aug. 25, 2012, the first spacecraft to do so.

On Sept. 5, 2017, NASA marked the 40th anniversary of its launch, as it continues to communicate with NASA’s Deep Space Network and send data back from four still-functioning instruments—the cosmic ray telescope, the low-energy charged particles experiment, the magnetometer, and the plasma waves experiment.

The Golden Record

Each of the Voyagers contain a “message,” prepared by a team headed by Carl Sagan, in the form of a 12-inch (30 cm) diameter gold-plated copper disc for potential extraterrestrials who might find the spacecraft. Like the plaques on Pioneers 10 and 11, the record has inscribed symbols to show the location of Earth relative to several pulsars.

The records also contain instructions to play them using a cartridge and a needle, much like a vinyl record player. The audio on the disc includes greetings in 55 languages, 35 sounds from life on Earth (such as whale songs, laughter, etc.), 90 minutes of generally Western music including everything from Mozart and Bach to Chuck Berry and Blind Willie Johnson. It also includes 115 images of life on Earth and recorded greetings from then U.S. President Jimmy Carter (1924– ) and then-UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim (1918–2007).

By January 2024, Voyager 1 was about 136 AU (15 billion miles, or 20 billion kilometers) from Earth, the farthest object created by humans, and moving at a velocity of about 38,000 mph (17.0 kilometers/second) relative to the Sun.

National Space Science Data Center: Voyager 1

A library of technical details and historic perspective.

Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration

A comprehensive history of missions sent to explore beyond Earth.

Discover More Topics From NASA

Our Solar System

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Voyager Golden Record Was Made

By Timothy Ferris

We inhabit a small planet orbiting a medium-sized star about two-thirds of the way out from the center of the Milky Way galaxy—around where Track 2 on an LP record might begin. In cosmic terms, we are tiny: were the galaxy the size of a typical LP, the sun and all its planets would fit inside an atom’s width. Yet there is something in us so expansive that, four decades ago, we made a time capsule full of music and photographs from Earth and flung it out into the universe. Indeed, we made two of them.

The time capsules, really a pair of phonograph records, were launched aboard the twin Voyager space probes in August and September of 1977. The craft spent thirteen years reconnoitering the sun’s outer planets, beaming back valuable data and images of incomparable beauty . In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first human-made object to leave the solar system, sailing through the doldrums where the stream of charged particles from our sun stalls against those of interstellar space. Today, the probes are so distant that their radio signals, travelling at the speed of light, take more than fifteen hours to reach Earth. They arrive with a strength of under a millionth of a billionth of a watt, so weak that the three dish antennas of the Deep Space Network’s interplanetary tracking system (in California, Spain, and Australia) had to be enlarged to stay in touch with them.