UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

Global fdi greenfield investment trends in tourism, share this content.

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

Tourism Investment Report 2020

In association with fdi intelligence from the financial times.

For the third year in a row, the UNWTO has partnered with the fDi intelligence from the Financial Times to develop a joint publication on Tourism Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) analyzing data on Greenfield investments trends. The relevance of this report is pivotal to governments and investors because it exposed data on flows of capital, and destinations for investments providing insight on market trends for the tourism recovery.

In times of uncertainty, expertise and trusted information is more important than ever. This report provides investment and market data that both investors and stakeholders will need to maximize their impact of the sector in terms of economic growth, job creation and sustainability. Especially when around 100-120 million direct tourism jobs are at risk, which threatens to roll back the progress we have made in establishing tourism as a driver towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). For this edition, the UNWTO’ Innovation, Digital Transformation and Investments department has developed an interactive report using data (2015-2019) from the fDi Intelligence on Tourism FDI.

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit the tourism sector hard; the data suggests that global FDI into tourism plummeted by 73.2% in the first half of 2020, compared with a year earlier. This put an end to the sector’s record high years. This data has a close relationship with the UNWTO’ scenarios for international tourist numbers decline, which could fall between 60 and 80% this year depending on the speed with which travel restrictions are lifted. This could translate into a loss of 850 million to 1.1 billion international tourist arrivals and a fall of $910 billion to $1.2 trillion in export revenues.

If you want to learn more, please register here

Although, the investment cycle remained strong throughout 2019, with tourism mobilizing $61.8bn in global FDI, which, in turn, created more than 135,000 jobs. The trend appeared particularly consistent in Latin America and the Caribbean, where FDI reached new record levels. For example it created more than 56.000 jobs in Mexico from 2015 – 2019. Tourism FDI was also strong in the Middle East and Africa, where it rose to the highest level in a decade. However, almost half of all tourism investments globally (46.51%) are made at top 10 countries. From which around 30% of projects are concentrated in five countries: United Kingdom, United States, Germany, China, and Spain. It is important to notice that more than 30% of projects and of capital investment announced in the tourism cluster between 2015 and 2019 occurred in 2019.

The major sub sector that has led tourism investments are consider traditional investments, with construction as the main driver for around 57% of total Greenfield investments from 2015 to 2019. As such, the trends in accommodation are around the sustainability where multinational companies are investing in green, and clean energy matrix of their operations. According to the fDi intelligence of the Financial Times, investors are paying increasing attention to the social and environmental footprint of the projects they assess in tourism. They seem willing to prioritize developments that lift communities and preserve ecosystems, as long as financial sustainability is also taken into account.

Finally, there is also an increasing number of non-traditional investments related to services around software technologies that include: Travel arrangement & reservation services, Internet publishing, web search among other, which represent around 32% of total investments considering investments between 2015 - 2019. This data invites to research more about investments in technology as a source of FDI in the tourism sector. The Travel Tech startups have been introducing innovations in the tourism ecosystem, and they are constantly changing business models attracting more investors.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made clear that sustainable tourism requires that sustainable investments are at the center of new solutions, and not just of traditional investments that promote and underpin economic growth and productivity. It has also highlighted the importance of non-traditional investments that enhance innovation through the creation and diffusion of new solutions to decarbonize the sector. To harness the advantages of investments, it is critical that governments promote policies as well as new investment vehicles to recover, retain and attract foreign direct investments. Only this way can we reimagine tourism and enhance the sector’s positive impact on people and planet as we accelerate the achievement of SDGs.

The UNWTO is developing a series of investment guidelines to understand and generate sustainable investments and promote innovations in the tourism ecosystem. If you are interested in the UNWTO’ reports and guidelines to understand, enable and mobilize tourism investments , we invite you to register to receive the our investment updates.

Please feel free to download the full report:

TOURISM INVESTMENT 2020

TOURISM INVESTMENT 2019

TOURISM INVESTMENT 2018

If you have questions about the report, or need more specific information about tourism investments white us an email to [email protected]

If you want to receive news about tourism investments please register in the bottom bellow.

10 Economic impacts of tourism + explanations + examples

There are many economic impacts of tourism, and it is important that we understand what they are and how we can maximise the positive economic impacts of tourism and minimise the negative economic impacts of tourism.

Many argue that the tourism industry is the largest industry in the world. While its actual value is difficult to accurately determine, the economic potential of the tourism industry is indisputable. In fact, it is because of the positive economic impacts that most destinations embark on their tourism journey.

There is, however, more than meets the eye in most cases. The positive economic impacts of tourism are often not as significant as anticipated. Furthermore, tourism activity tends to bring with it unwanted and often unexpected negative economic impacts of tourism.

In this article I will discuss the importance of understanding the economic impacts of tourism and what the economic impacts of tourism might be. A range of positive and negative impacts are discussed and case studies are provided.

At the end of the post I have provided some additional reading on the economic impacts of tourism for tourism stakeholders , students and those who are interested in learning more.

Foreign exchange earnings

Contribution to government revenues, employment generation, contribution to local economies, development of the private sector, infrastructure cost, increase in prices, economic dependence of the local community on tourism, foreign ownership and management, economic impacts of tourism: conclusion, further reading on the economic impacts of tourism, the economic impacts of tourism: why governments invest.

Tourism brings with it huge economic potential for a destination that wishes to develop their tourism industry. Employment, currency exchange, imports and taxes are just a few of the ways that tourism can bring money into a destination.

In recent years, tourism numbers have increased globally at exponential rates, as shown in the World Tourism Organisation data below.

There are a number of reasons for this growth including improvements in technology, increases in disposable income, the growth of budget airlines and consumer desires to travel further, to new destinations and more often.

Here are a few facts about the economic importance of the tourism industry globally:

- The tourism economy represents 5 percent of world GDP

- Tourism contributes to 6-7 percent of total employment

- International tourism ranks fourth (after fuels, chemicals and automotive products) in global exports

- The tourism industry is valued at US$1trillion a year

- Tourism accounts for 30 percent of the world’s exports of commercial services

- Tourism accounts for 6 percent of total exports

- 1.4billion international tourists were recorded in 2018 (UNWTO)

- In over 150 countries, tourism is one of five top export earners

- Tourism is the main source of foreign exchange for one-third of developing countries and one-half of less economically developed countries (LEDCs)

There is a wealth of data about the economic value of tourism worldwide, with lots of handy graphs and charts in the United Nations Economic Impact Report .

In short, tourism is an example of an economic policy pursued by governments because:

- it brings in foreign exchange

- it generates employment

- it creates economic activity

Building and developing a tourism industry, however, involves a lot of initial and ongoing expenditure. The airport may need expanding. The beaches need to be regularly cleaned. New roads may need to be built. All of this takes money, which is usually a financial outlay required by the Government.

For governments, decisions have to be made regarding their expenditure. They must ask questions such as:

How much money should be spent on the provision of social services such as health, education, housing?

How much should be spent on building new tourism facilities or maintaining existing ones?

If financial investment and resources are provided for tourism, the issue of opportunity costs arises.

By opportunity costs, I mean that by spending money on tourism, money will not be spent somewhere else. Think of it like this- we all have a specified amount of money and when it runs out, it runs out. If we decide to buy the new shoes instead of going out for dinner than we might look great, but have nowhere to go…!

In tourism, this means that the money and resources that are used for one purpose may not then be available to be used for other purposes. Some destinations have been known to spend more money on tourism than on providing education or healthcare for the people who live there, for example.

This can be said for other stakeholders of the tourism industry too.

There are a number of independent, franchised or multinational investors who play an important role in the industry. They may own hotels, roads or land amongst other aspects that are important players in the overall success of the tourism industry. Many businesses and individuals will take out loans to help fund their initial ventures.

So investing in tourism is big business, that much is clear. What what are the positive and negative impacts of this?

Positive economic impacts of tourism

So what are the positive economic impacts of tourism? As I explained, most destinations choose to invest their time and money into tourism because of the positive economic impacts that they hope to achieve. There are a range of possible positive economic impacts. I will explain the most common economic benefits of tourism below.

One of the biggest benefits of tourism is the ability to make money through foreign exchange earnings.

Tourism expenditures generate income to the host economy. The money that the country makes from tourism can then be reinvested in the economy. How a destination manages their finances differs around the world; some destinations may spend this money on growing their tourism industry further, some may spend this money on public services such as education or healthcare and some destinations suffer extreme corruption so nobody really knows where the money ends up!

Some currencies are worth more than others and so some countries will target tourists from particular areas. I remember when I visited Goa and somebody helped to carry my luggage at the airport. I wanted to give them a small tip and handed them some Rupees only to be told that the young man would prefer a British Pound!

Currencies that are strong are generally the most desirable currencies. This typically includes the British Pound, American, Australian and Singapore Dollar and the Euro .

Tourism is one of the top five export categories for as many as 83% of countries and is a main source of foreign exchange earnings for at least 38% of countries.

Tourism can help to raise money that it then invested elsewhere by the Government. There are two main ways that this money is accumulated.

Direct contributions are generated by taxes on incomes from tourism employment and tourism businesses and things such as departure taxes.

Taxes differ considerably between destinations. I will never forget the first time that I was asked to pay a departure tax (I had never heard of it before then), because I was on my way home from a six month backpacking trip and I was almost out of money!

Japan is known for its high departure taxes. Here is a video by a travel blogger explaining how it works.

According to the World Tourism Organisation, the direct contribution of Travel & Tourism to GDP in 2018 was $2,750.7billion (3.2% of GDP). This is forecast to rise by 3.6% to $2,849.2billion in 2019.

Indirect contributions come from goods and services supplied to tourists which are not directly related to the tourism industry.

Take food, for example. A tourist may buy food at a local supermarket. The supermarket is not directly associated with tourism, but if it wasn’t for tourism its revenues wouldn’t be as high because the tourists would not shop there.

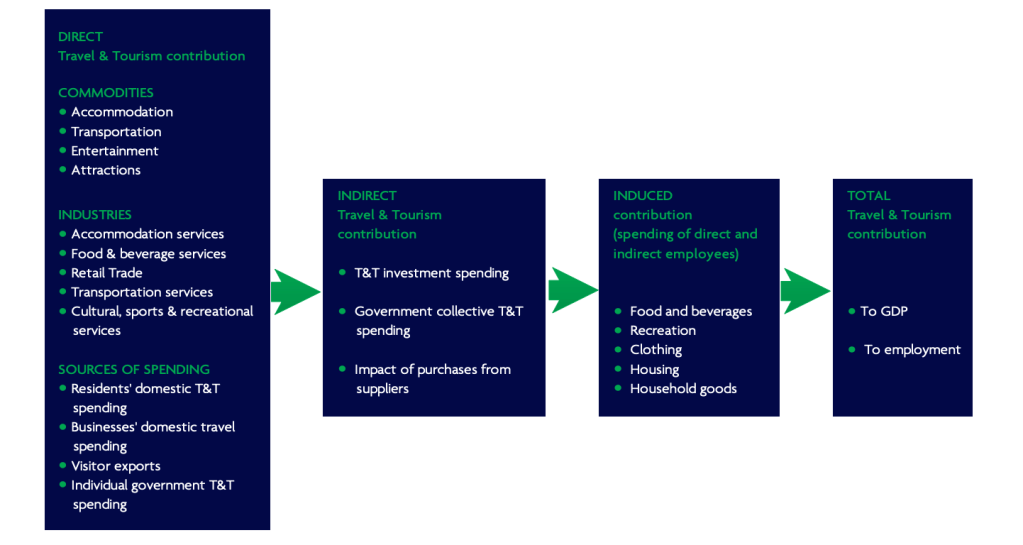

There is also the income that is generated through induced contributions . This accounts for money spent by the people who are employed in the tourism industry. This might include costs for housing, food, clothing and leisure Activities amongst others. This will all contribute to an increase in economic activity in the area where tourism is being developed.

The rapid expansion of international tourism has led to significant employment creation. From hotel managers to theme park operatives to cleaners, tourism creates many employment opportunities. Tourism supports some 7% of the world’s workers.

There are two types of employment in the tourism industry: direct and indirect.

Direct employment includes jobs that are immediately associated with the tourism industry. This might include hotel staff, restaurant staff or taxi drivers, to name a few.

Indirect employment includes jobs which are not technically based in the tourism industry, but are related to the tourism industry. Take a fisherman, for example. He does not have any contact of dealings with tourists. BUT he does sell his fish to the hotel which serves tourists. So he is indirectly employed by the tourism industry, because without the tourists he would not be supplying the fish to the hotel.

It is because of these indirect relationships, that it is very difficult to accurately measure the economic value of tourism.

It is also difficult to say how many people are employed, directly and indirectly, within the tourism industry.

Furthermore, many informal employments may not be officially accounted for. Think tut tut driver in Cambodia or street seller in The Gambia – these people are not likely to be registered by the state and therefore their earnings are not declared.

It is for this reason that some suggest that the actual economic benefits of tourism may be as high as double that of the recorded figures!

All of the money raised, whether through formal or informal means, has the potential to contribute to the local economy.

If sustainable tourism is demonstrated, money will be directed to areas that will benefit the local community most.

There may be pro-poor tourism initiatives (tourism which is intended to help the poor) or volunteer tourism projects.

The government may reinvest money towards public services and money earned by tourism employees will be spent in the local community. This is known as the multiplier effect.

The multiplier effect relates to spending in one place creating economic benefits elsewhere. Tourism can do wonders for a destination in areas that may seem to be completely unrelated to tourism, but which are actually connected somewhere in the economic system.

Let me give you an example.

A tourist buys an omelet and a glass of orange juice for their breakfast in the restaurant of their hotel. This simple transaction actually has a significant multiplier effect. Below I have listed just a few of the effects of the tourist buying this breakfast.

The waiter is paid a salary- he spends his salary on schooling for his kids- the school has more money to spend on equipment- the standard of education at the school increases- the kids graduate with better qualifications- as adults, they secure better paying jobs- they can then spend more money in the local community…

The restaurant purchases eggs from a local farmer- the farmer uses that money to buy some more chickens- the chicken breeder uses that money to improve the standards of their cages, meaning that the chickens are healthier, live longer and lay more eggs- they can now sell the chickens for a higher price- the increased money made means that they can hire an extra employee- the employee spends his income in the local community…

The restaurant purchase the oranges from a local supplier- the supplier uses this money to pay the lorry driver who transports the oranges- the lorry driver pays road tax- the Government uses said road tax income to fix pot holes in the road- the improved roads make journeys quicker for the local community…

So as you can see, that breakfast that the tourist probably gave not another thought to after taking his last mouthful of egg, actually had the potential to have a significant economic impact on the local community!

The private sector has continuously developed within the tourism industry and owning a business within the private sector can be extremely profitable; making this a positive economic impact of tourism.

Whilst many businesses that you will come across are multinational, internationally-owned organisations (which contribute towards economic leakage ).

Many are also owned by the local community. This is the case even more so in recent years due to the rise in the popularity of the sharing economy and the likes of Airbnb and Uber, which encourage the growth of businesses within the local community.

Every destination is different with regards to how they manage the development of the private sector in tourism.

Some destinations do not allow multinational organisations for fear that they will steal business and thus profits away from local people. I have seen this myself in Italy when I was in search of a Starbucks mug for my collection , only to find that Italy has not allowed the company to open up any shops in their country because they are very proud of their individually-owned coffee shops.

Negative economic impacts of tourism

Unfortunately, the tourism industry doesn’t always smell of roses and there are also several negative economic impacts of tourism.

There are many hidden costs to tourism, which can have unfavourable economic effects on the host community.

Whilst such negative impacts are well documented in the tourism literature, many tourists are unaware of the negative effects that their actions may cause. Likewise, many destinations who are inexperienced or uneducated in tourism and economics may not be aware of the problems that can occur if tourism is not management properly.

Below, I will outline the most prominent negative economic impacts of tourism.

Economic leakage in tourism is one of the major negative economic impacts of tourism. This is when money spent does not remain in the country but ends up elsewhere; therefore limiting the economic benefits of tourism to the host destination.

The biggest culprits of economic leakage are multinational and internationally-owned corporations, all-inclusive holidays and enclave tourism.

I have written a detailed post on the concept of economic leakage in tourism, you can take a look here- Economic leakage in tourism explained .

Another one of the negative economic impacts of tourism is the cost of infrastructure. Tourism development can cost the local government and local taxpayers a great deal of money.

Tourism may require the government to improve the airport, roads and other infrastructure, which are costly. The development of the third runway at London Heathrow, for example, is estimated to cost £18.6billion!

Money spent in these areas may reduce government money needed in other critical areas such as education and health, as I outlined previously in my discussion on opportunity costs.

One of the most obvious economic impacts of tourism is that the very presence of tourism increases prices in the local area.

Have you ever tried to buy a can of Coke in the supermarket in your hotel? Or the bar on the beachfront? Walk five minutes down the road and try buying that same can in a local shop- I promise you, in the majority of cases you will see a BIG difference In cost! (For more travel hacks like this subscribe to my newsletter – I send out lots of tips, tricks and coupons!)

Increasing demand for basic services and goods from tourists will often cause price hikes that negatively impact local residents whose income does not increase proportionately.

Tourism development and the related rise in real estate demand may dramatically increase building costs and land values. This often means that local people will be forced to move away from the area that tourism is located, known as gentrification.

Taking measures to ensure that tourism is managed sustainably can help to mitigate this negative economic impact of tourism. Techniques such as employing only local people, limiting the number of all-inclusive hotels and encouraging the purchasing of local products and services can all help.

Another one of the major economic impacts of tourism is dependency. Many countries run the risk of becoming too dependant on tourism. The country sees $ signs and places all of its efforts in tourism. Whilst this can work out well, it is also risky business!

If for some reason tourism begins to lack in a destination, then it is important that the destination has alternative methods of making money. If they don’t, then they run the risk of being in severe financial difficulty if there is a decline in their tourism industry.

In The Gambia, for instance, 30% of the workforce depends directly or indirectly on tourism. In small island developing states, percentages can range from 83% in the Maldives to 21% in the Seychelles and 34% in Jamaica.

There are a number of reasons that tourism could decline in a destination.

The Gambia has experienced this just recently when they had a double hit on their tourism industry. The first hit was due to political instability in the country, which has put many tourists off visiting, and the second was when airline Monarch went bust, as they had a large market share in flights to The Gambia.

Other issues that could result in a decline in tourism includes economic recession, natural disasters and changing tourism patterns. Over-reliance on tourism carries risks to tourism-dependent economies, which can have devastating consequences.

The last of the negative economic impacts of tourism that I will discuss is that of foreign ownership and management.

As enterprise in the developed world becomes increasingly expensive, many businesses choose to go abroad. Whilst this may save the business money, it is usually not so beneficial for the economy of the host destination.

Foreign companies often bring with them their own staff, thus limiting the economic impact of increased employment. They will usually also export a large proportion of their income to the country where they are based. You can read more on this in my post on economic leakage in tourism .

As I have demonstrated in this post, tourism is a significant economic driver the world over. However, not all economic impacts of tourism are positive. In order to ensure that the economic impacts of tourism are maximised, careful management of the tourism industry is required.

If you enjoyed this article on the economic impacts of tourism I am sure that you will love these too-

- Environmental impacts of tourism

- The 3 types of travel and tourism organisations

- 150 types of tourism! The ultimate tourism glossary

- 50 fascinating facts about the travel and tourism industry

- 23 Types of Water Transport To Keep You Afloat

Economic Leakage in Tourism: What It Is and How to Prevent It

Tourism is a significant driver of economic and social development. It is responsible for generating income, employment, investment, and ultimately, improving the quality of life for locals. But local communities in different destinations are not fully experiencing the benefits of this activity due to economic leakage in tourism.

When it happens, all the investment and effort put into growing tourism doesn’t pay off once part of the money generated by this industry leaves the host city or country.

This blog covers what economic leakage in tourism is, its consequences and what actions to take in order to keep tourists’ expenditures inside your destination.

What is economic leakage in tourism?

Tourism leakage happens when the revenue generated through tourism is lost to other countries or economies.

Tourism is an activity that traditionally brings foreign currency into a country’s economy. But due to globalization and travel conglomerates , this money is likely to leave the host country preventing the economic and social development of touristic areas.

Historically, economic leakage in tourism is more significant in developing countries . Sometimes it can nearly neutralize the money generated by tourism activity.

In Fiji, it is estimated that 60% of the money earned through tourism ends up leaving the country . In another study, tourism leakage estimates range from 40% in India to 80% in the Caribbean .

What triggers economic leakage in tourism?

Leakage is intrinsic to tourism and is present in all countries. However, its intensity varies in degree depending on how developed the destination is and the actions taken in order to prevent it.

Basically, leakage occurs through six main mechanisms :

1) Good and Service

In order to supply travelers’ demands, many destinations import goods and services. This type of economic leakage in tourism is more noticeable in islands, which are highly dependent on imports.

2) Infrastructure

In this case, tourism leakage happens when the host country doesn’t have the ability or technology to build tourism-related infrastructure and depends on foreign companies for it. For example, to build airports and ports or to implement a new travel technology.

3) Foreign ownership

When the tourism industry is not well-developed in a destination, it’s common for governments to attract foreign investment in order to start the activity in that area. However, when foreigners have ownership of the touristic infrastructure, the profits generated by this activity are taken away from the host market. That is the case in a destination dominated by international resort chains, for example.

4) Promotional expenditures

Having an international presence is paramount for many destinations, on the other hand, it’s a source of tourism leakage. When a destination invests in attracting foreign visitors , the money spent on advertisement and publicity goes abroad.

5) Tax exemptions

When a destination gives tax exemptions to foreign investors it is giving up tourism income. This strategy to grow the tourism industry is common in developing destinations, but it should be well planned in order to not harm the local community.

6) Foreign employment

During the high season, the increase in demand leads to the opening of temporary job opportunities. This often attracts foreign workers interested in making money and leaving the destination after the end of the season.

Why is economic leakage in tourism an issue for destinations?

Although tourism has lots of benefits —it boosts the local economy, creates new jobs, promotes cultural exchange— on the other hand, it also has negative impacts :

- Puts pressure on the local infrastructure

- Impacts the environment

- Changes the daily life of residents

- Drains local resources

- Affects the local production chain

- Increases the demand for goods, services and accommodations, which rises their prices

When the money earned through tourism leaves the host destination, little or nothing can be done in order to mitigate these bad impacts and promote social, cultural and environmental well-being for the local community.

Hence, tourism stops being an attractive investment and turns into an issue for the destination.

How can tourism stakeholders prevent tourists’ expenditures from leaving a destination?

Tourism leakage is harmful to destinations, especially the ones that rely on tourism as the primary source of income.

In order to prevent it, the government, destination managers, travel companies, the local industry, residents and visitors should work together to make sure the money spent on this activity is reaching the right pockets.

Some actions that destination leaders can take in order to reduce economic leakage in tourism are:

- Support local suppliers

The host community is a great source of workforce, services, and products that should be integrated into the local tourism industry. Destination managers should incentivize travel companies to buy from local producers before searching for suppliers abroad.

- Attract conscious travelers

Destination marketers should invest in campaigns to attract conscious travelers . This type of traveler knows the importance of tourism as an economic and social driver for the host community. They make sustainable choices, support the local suppliers and protect the environment.

- Promote niche tourism

Travelers looking for a niched experience are interested in discovering the local culture, history, culinary and hidden gems. Unlike mass tourism, which is usually offered by international companies and associated with overtourism, niche tourism is often offered by locals to a small group of travelers.

- Incentivize local companies

Instead of giving tax exemptions to international companies, try reducing the taxes for local accommodations, operators and producers. A relief in taxes gives a chance for the local tourism ecosystem to flourish.

- Limitate the presence of multinational corporations

All-inclusive packages are very popular among travelers. The issue is that about 80% of travelers’ expenditures on these packages go to international corporations . By restricting the presence of these companies in a destination, travelers should turn to local providers in order to have a complete stay.

- Stimulate the diversification of the local economy

The more dependent on tourism a destination is, the bigger the tourism leakage. A destination with a diversified economy has more bargaining power when dealing with international investors.

- Digitalize the tourism offer

Increasing the online exposure of local travel providers is a way to drive them more bookings. Destinations that are digitalizing their tourism offer, such as Visit Zagorije , not only make local companies more competitive but also facilitate the booking process for visitors.

Tourism leakage is an issue all destinations have to deal with. When not addressed, tourism income is drained out of the local community, preventing its economic, social and environmental development.

In this article, we have presented seven initiatives to fight back economic leakage in tourism :

If you are a destination manager or marketer interested in empowering your local tourism stakeholders, SmartDestination is the right partner for you. They are a group of award-winning tech companies specialized in travel, tourism and hospitality with a complete solution to digitalize your tourism offer.

Contact them if you want to boost your travel and tourism product.

ORIOLY on August 17, 2022

by Felipe Fonseca

Subscribe to our newsletter

Receive the latest news and resources in your inbox

Thank you for subscribing the newsletter

Low Budget Digital Marketing Strategies for Tour Operators

In this ebook you will learn strategies to boost your digital marketing efforts, and the best part, at a low and even zero cost for your business.

The Ultimate Guide to Mastering Trip Advisor

TripAdvisor is an excellent tool to sell tours and activities online and this guide will teach everything you need to know to master it.

A Simple Guide on How to Sell Tours With Facebook

Zuckerberg’s platform is by far the most popular among all social media. So why not selling tours and activities with Facebook help?

Comprehensive Guide on Digital Marketing in Tourism for 2021

Online marketing is a new thing and it changes fast, for that reason we made this eBook where we compiled the latest online marketing trends in tourism!

Other resources

Live Virtual Tours: Everything You Need

5 Channel Ideas to Sell your Tours

How to start a food tour business, related articles.

Orioly updates and new functionalities: Coupon system, improved POS Desk application and more

Tour organizers can assign coupons to partners, send documents in Polish, and use the improved POS Desk application.

How to Manage Tour Guides: A Practical Guide to Hire, Lead, and Inspire Your Staff

The travel industry is a dynamic and competitive field, focused on providing customers with memorable and amazing experiences, and the quality of your tour guides can significantly impact that. That’s why managing and inspiring these professionals, as well as hiring the best of them, is crucial to ensuring your business’s success and bringing a smile […]

How to Enable Guests to Book Additional Activities with Accommodation?

Discover the advantages you gain as an accommodation provider by offering the booking of additional activities through Orioly.

Is Caribbean tourism in overdrive? Investigating the antecedents and effects of overtourism in sovereign and nonsovereign small island tourism economies (SITEs)

International Hospitality Review

ISSN : 2516-8142

Article publication date: 10 February 2021

Issue publication date: 21 June 2021

Drawing on theories of development economics and sustainable tourism, this research explores the differences between sovereign and nonsovereign small island tourism economies (SITEs) and identifies the antecedents and effects of overtourism in the Caribbean.

Design/methodology/approach

The research design is based on a comparative case study of selected Caribbean SITEs. Case study research involves a detailed empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context. The main purpose of a case study is to provide a contextual analysis of the conditions and processes involved in the phenomenon under study. A comparative case study is an appropriate research methodology to explore new multi-faceted concepts with limited empirical evidence.

The results confirm previous studies that nonsovereign SITEs have a distinctive overdrive toward tourism specialization. Moreover, the findings indicate that overtourism is driven by both global and domestic policy factors and generates significant economic volatility, social inequality and ecological stress. The paper discusses the tourism policy implications of the evolving economic disconnectedness, environmental decay and social tensions in SITEs in the Caribbean.

Originality/value

Policy recommendations are presented for transitioning toward a more inclusive development and strengthening the resilience of small island tourism development in the Caribbean.

- Small island tourism economy

- Overtourism

- Nonsovereign island states

Peterson, R. and DiPietro, R.B. (2021), "Is Caribbean tourism in overdrive? Investigating the antecedents and effects of overtourism in sovereign and nonsovereign small island tourism economies (SITEs)", International Hospitality Review , Vol. 35 No. 1, pp. 19-40. https://doi.org/10.1108/IHR-07-2020-0022

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Ryan Peterson and Robin B. DiPietro

Published in International Hospitality Review . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

It is a truism that international tourism is part and parcel of the Caribbean. Over the past century, tourism arrivals have grown tenfold, from less than five million visitors during the early 1970s to well over 36 million tourists in 2017 ( Statista, 2020 ). Since the turn of the century, Caribbean tourism growth tripled ( United Nations World Tourism Organization [UNWTO], 2019 ) and is expected to continue to grow over the next decade ( World Travel and Tourism Council [WTTC], 2019 ). Recent tourism industry reports indicate that the Caribbean is gearing up for another tourism growth burst, attracting new hotel investors and well over 31,000 new accommodations in the construction pipeline ( Britell, 2020 ). The Caribbean is indeed one of the most tourism-intense regions of the world with international tourism contributing, on average, to 20% of exports, 15% of GDP (gross domestic product) and 14% of labor ( WTTC, 2019 ). Likewise, accounting for at least 13% of capital investments ( WTTC, 2019 ), international tourism is one of the most resource-intense industries, including financial, human and natural resources ( McElroy, 2006 ). In the wake of the global COVID-19 pandemic, the unprecedented plunge in Caribbean travel and tourism is a clear and present sign of both the value and the vulnerability of tourism across the Caribbean ( International Monetary Fund – IMF, 2020 ).

Despite this significant and continued tourism growth, there are increasing signs that economic growth has largely stagnated across the Caribbean, especially in the smaller and more tourism-dependent island economies ( Acevedo et al. , 2017 ; Peterson, 2019 ; Leigh et al. , 2017 ). Initial evidence suggests that the surge in international tourism has not contributed significantly to the lackluster economic growth since the early 2000s ( Chamon et al. , 2017 ). Whereas tourism arrivals and accommodations have expanded and continue to grow across the Caribbean, tourism expenditures have not increased commensurately ( Acevedo et al. , 2017 ). Therefore, the purpose of this exploratory study is to (1) investigate the status and qualities of overtourism in sovereign and nonsovereign Caribbean small island tourism economies (SITEs) and (2) examine the antecedents and effects of overtourism in mature SITEs in order to determine implications for industry and academics to help create a more sustainable model for small island tourism development.

This reality of overtourism is consistent with previous studies reporting stagnant growth and diminishing productivity in Caribbean tourism economies ( Acevedo et al. , 2017 ; Peterson, 2017 ). Moreover, the performance of SITEs has lagged other (non-) Caribbean small island economies for at least a decade ( Acevedo et al. , 2017 ). Thus, the confluence of enduring tourism growth with diminishing economic development in SITEs raises questions about the role and contribution of tourism for sustainable and inclusive development in the Caribbean ( United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG), 2018 ), especially considering the complex of economic and environmental shocks in addition to the longstanding social vulnerabilities and institutional weaknesses (International Monetary Fund [IMF], 2019 ; Peterson, 2019 ).

When a country has a focus on tourism as an economic advantage and a significant export industry, it is traditionally associated with economic production and growth ( Brida et al. , 2016 ; Cannonier and Galloway, 2019 ; Croes, 2006 ; Croes et al. , 2021 ; Marsiglio, 2018 ). There are also potential adverse externalities related to this tourism specialization ( Daye et al. , 2008 ; Dodds and Butler, 2019a ; Duval, 2004 ; Gossling, 2002 ; Hall and Williams, 2008 ; McElroy, 2003 ; Peterson, 2009 ; Wilkinson, 1989 ). The tourism-led growth hypothesis proposes international tourism drives economic growth ( Brida et al. , 2016 ). However, several studies indicate that this relationship is intermediated and moderated by several other contingency factors and tourism destination-specific conditions, including the capacity to adapt to and absorb large-scale, high-pace tourism construction and growth ( Bishop, 2010 ; Cole, 2007 ; McElroy, 2006 ). The relationship between tourism specialization and economic growth is moderated by absorptive capacities ( Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012 ; Baldacchino, 2006 ; Brautigam and Woolcock, 2001 ; Peterson, 2017 ), which describe the optimum level of tourism specialization that can be assimilated and absorbed by an economy before reaching an inflection point after which tourism specialization experiences diminishing returns and negative externalities ( Dodds and Butler, 2019a ; Marsiglio, 2018 ).

When reviewing the history of tourism in the Caribbean, it is increasingly apparent that growth rather than development remains the overriding focus, i.e. the quality of life for residents and, in turn, the quality of experience for visitors have not always met the various principles of sustainable tourism ( Daye et al. , 2008 ; Duval, 2004 ; Joppe, 2019 ; Scheyvens and Biddulph, 2017 ). In fact, economic considerations and benefits of tourism specialization tend to induce tourism myopia – a short-term growth orientation on tourism arrivals, receipts and (tax) revenues – and trigger a gradual tourism overshoot of socioecological ceilings with significant costs in the medium to long term ( Dodds and Butler, 2019b ; Ewing-Chow, 2019 ; Joppe, 2019 ; Marsiglio, 2017 ; Raworth, 2017 ).

Crandall (1994) concludes that while tourism is accepted as a significant boon to local economies, there is little realization on the part of government, tourism authorities and investors that tourism leads to economic spillovers, social changes and ecological challenges, especially when unplanned or uncontrolled. Although, certainly, this is not a new experience, this accelerating tourism spillover effect has recently been coined “overtourism” ( Dodds and Butler, 2019b ; Goodwin, 2017 ). Thus, coping with the short-term economic success of tourism growth is inextricably linked to managing and mitigating the risks of overtourism in contemporary tourism destinations ( WTTC, 2019 ).

Whereas previous research on international tourism in the Caribbean focuses almost exclusively on the sovereign (independent) small island tourism states, nonsovereign (dependent) island tourism economies are generally less scrutinized and often excluded, largely due to their nonsovereign political status. Ironically, these subnational island jurisdictions are oftentimes relatively more tourism intense and prone to overtourism ( Baldacchino, 2006 ; McElroy, 2006 ; Peterson, 2019 ; WTTC, 2019 ). Therefore, the heterogenous nature of Caribbean tourism economies, consisting of both sovereign island states and subnational jurisdictions, calls for the explicit acknowledgment and incorporation of subnational island jurisdictions in tourism studies, especially considering the political economic context of small island tourism development ( Armstrong and Read, 2000 ; Daye et al. , 2008 ; McElroy, 2006 ). In fact, over the past decade, several studies have called for research on the political economy of small island tourism development in the (British, Dutch and French) dependencies in the Caribbean ( Baldacchino, 2006 ; Bishop, 2010 ; Daye et al. , 2008 ; McElroy, 2006 ).

Consequently, this paper addresses the current state of overtourism in sovereign and nonsovereign SITEs in the Caribbean. The aim of this exploratory study is to (1) investigate the status and qualities of overtourism in sovereign and nonsovereign Caribbean SITEs and (2) examine the antecedents and effects of overtourism in mature SITEs. In Section 2 , the theoretical background of this study is discussed by reviewing the conceptual origins and mechanisms of overtourism. The research methodology is described in Section 3 , followed by a presentation of the main findings, while conclusions and recommendations are presented in the final part of the paper.

2. Theoretical background

In general, overtourism describes the adverse impacts of uncontrolled tourism growth – an overshoot of tourism – that influences the quality of life and the well-being of citizens and the degradation of natural habitats and ecologies, which result in diminishing visitor experiences and expenditures, and consequently stagnating economic returns ( United Nations World Tourism Organization – UNWTO, 2018 ). Overtourism portrays relentless, frequently unregulated, tourism growth that has moved beyond the level of acceptable change and absorptive capacity in a destination due to significant levels of tourism intensity (total visitors to population), tourism density (visitors per km 2 ) and tourism dependency (tourism exports to GDP) ( McElroy, 2006 ; World Travel and Tourism Council – WTTC, 2019 ). The compounding and composite effects result in significant pressures on infrastructure (i.e. congestion, transportation and energy), resource consumption and pollution (i.e. leakage and waste), spatial and cultural alienation (i.e. real estate and social identity) and visitors' experiences and residents' quality of life ( Center for Responsible Travel–CERT, 2018 ; World Travel and Tourism Council – WTTC, 2019 ).

The genesis of overtourism dates back to at least the 1970s and 1980s when initial concerns were raised about the potential adverse social and environmental impacts of uncontrolled tourism growth and consequently the long-run economic repercussions thereof ( Budowski, 1976 ; Butler, 1980 ; Cohen, 1978 ; Doxey, 1978 ; Dunkel, 1984 ; Farrell and Runyan, 1991 ; Getz, 1983 ; Holder, 1988 ; Mathieson and Wall, 1982 ; Richter, 1994 ; Wilkinson, 1989 ). By the early 2000s, several empirical studies reported on the negative externalities of tourism in SITEs ( Bishop, 2010 ; Duval, 2004 ; McElroy, 2003 , 2006 ; Sheller, 2003 ). Over the past decade, further evidence has been forthcoming on the role and rise of overtourism, albeit mainly focused on metropolitan areas and cities ( Capocchi et al. , 2019 ; CERT, 2018 ; Dodds and Butler, 2019b ).

As a concept, overtourism is rooted in development economics and discussions on overdevelopment, overdependency and overconsumption ( Kohr, 1977 ; Meier and Stiglitz, 2001 ). From a postdevelopment theoretical perspective ( Cowen and Shenton, 1996 ), overtourism refers to the social inequality and the environmental destruction due to excessive tourism consumption and tourism-related infrastructure expansion ( Raworth, 2017 ). Overtourism is conceptually embedded in the study of how economies grow and societies change over the course of history ( Meier and Stiglitz, 2001 ) and is frequently viewed in negative terms as the mutually constitutive reverse of inclusive development ( Gupta and Vegeling, 2016 ; UNSDG, 2018 ; World Bank, 2018 ).

In development economics, it is not only the rate of real GDP per capita growth that matters but also more importantly the pattern of labor force participation and income distribution in growth ( Meier, 2001 ). Inclusive development focuses on productive employment as a means of increasing income as well as raising standards of living and economic well-being ( Gupta and Vegeling, 2016 ; Ianchovichina and Lundstrom; 2009 ; Rainir and Ramos, 2013 ; Rauniyar and Kanbur, 2010 ). Gupta and Vegeling (2016) emphasize the social and ecological aspects of inclusive development. Whereas social elements address citizen well-being and participation in labor and consumption markets, ecological elements concentrate on the conservation of local ecosystems, the management of ecosystem services and the regulation of environmental resources. Inclusive development stems from the realization that relentless economic growth often gives rise to negative externalities, extractive resource depletions and exploitative labor practices ( Raworth, 2017 ), which are clear and present features of overtourism and readily acknowledged in SITEs ( Daye et al. , 2008 ; Duval, 2004 ; Island Resource Foundation, 1996 ; McElroy, 2006 ; Pattullo, 1996 ; Sheller, 2003 ).

According to Scheyvens and Biddulph (2017) , one of the most enduring critiques of tourism is its noninclusive development. They contend that tourism oftentimes provides opportunities for the privileged, creating profits for international (nonlocal) resorts and building exclusive enclaves for the rich, thereby excluding the indigenous community, marginalizing local cultures and lifestyles and depleting scarce natural resources ( Scheyvens and Biddulph, 2017 ). In reflecting on the tourism overdependency in the Caribbean, Daye et al. (2008) indicate that there is significant economic volatility and leakage due to the outflow of capital. Duval (2004) concludes that if left uncontrolled, Caribbean tourism often leads to environmentally extractive and socially exclusive developments, which in the long run undermine future economic development. It is the unbalanced and unequal distribution of benefits and costs amongst stakeholders that nourishes overtourism.

Overtourism extends previous theoretical frameworks and models of tourism lifecycles and complex adaptive tourism systems. The origins can be traced back to notions of the tourism destination life cycle ( Butler, 1980 ) and tourism carrying capacity ( Mathieson and Wall, 1982 ), which have been widely discussed in the Caribbean. The concept of overtourism underscores the nonlinear, interdependent and dynamic nature of tourism systems, which encompass several interacting social, political, economic, ecological and digital subsystems, especially within the small(er) scale of island economies ( Peterson et al. , 2017 ). These complex adaptive tourism systems are “nested” or embedded within social ecologies and often evolve in distinct ways with extensive cascades of uncertain and oftentimes path dependent and long-term effects ( Dodds and Butler, 2019b ; Farrell and Twining-Ward, 2004 ).

In reflecting on the growth of Caribbean tourism, McElroy (2006) contends that part of the problem in the Caribbean is that much of the tourism growth during the late 1990s was too fast and fragmented. According to Farrell and Runyan (1991) , this rapid and unbalanced growth of tourism produces an inherent propensity for environmental overrun and sociocultural disruption, which in due course would affect industry viability and economic sustainability. As the intensity and concentration of tourism growth increases, the capacity of delicate socioecological island systems to absorb these changes can be drastically exceeded and may produce undesirable resource degradation ( Farrell and Runyan, 1991 ).

Due to their relatively limited size and scale, small states and islands tend to be more susceptible to external pressures and internal disturbances. Unlike the tangible economic benefits (e.g. employment exports, and foreign exchange earnings) that accrue in the short term, the long-term costs (e.g. beach erosion, coastal pollution, congestion and social inequality and poverty) often remain concealed until critical thresholds are crossed ( McElroy, 2003 ). Whereas exogenous shocks occur in a sudden and disruptive manner, the externalities of overtourism cascade gradually over time until spilling over into the public domain.

The case in point is especially poignant in Caribbean SITEs that rely on their natural and social ecologies for safeguarding economic development and well-being. Whereas sustainable tourism requires the conservation of ecological integrity and environmental resources, its production is, paradoxically, largely dependent upon the consumption of nature-based tourism experiences ( Williams and Ponsford, 2008 ). Likewise, whereas much of Caribbean tourism is staged by its cultural authenticity and natural hospitality, its production is labor-intensive with exhaustive demands on emotional labor ( Shani et al. , 2014 ; Sönmez et al. , 2017 ). This ambiguity has epitomized much of the progress, pitfalls and perils of Caribbean tourism over the past century ( Duval, 2004 ).

Higher levels of overtourism in Caribbean SITEs are positively associated with lower labor force participation, more ecological stress and higher economic volatility.

The impact of overtourism in Caribbean SITEs is transmitted through both direct channels as well as indirect channels.

Previous studies indicate that overtourism stems from the complex dynamics of international tourism demand and local tourism supply ( Acevedo et al. , 2017 ; Capocchi et al. , 2019 ; Daye et al. , 2008 ; Cole, 2007 ; Dodds and Butler, 2019b ; Farrell and Twining-Ward, 2004 ; Joppe, 2019 ; Koens et al. , 2018 ; McElroy, 2006 . In reviewing the progressive development and potential challenges of tourism growth across SITEs, McElroy (2003 , 2006 ) discusses different interrelated causes of a tourism overrun, defined as high-density tourism with damaging levels of visitation due to tourism's sociocultural pressures and environmental footprint. The critical factors that spur overtourism in the Caribbean include the substantial inflow of foreign private tourism investments; the significant stock and rapid expansion of large-scale accommodation facilities; the growth in air traffic and cruise calls; the increase in labor immigration and the subsequent rise in unplanned coastal urbanization and real-estate infrastructures ( McElroy, 2003 , 2006 ). Previous studies indeed confirm that this system of an interlocked tourism supply chain, including the interlinked growth in tourism investments and airlift and the subsequent expansion of accommodations and required labor, contributes to surging levels of tourism intensity and density in the Caribbean ( Acevedo et al. , 2017 ), which gradually engender a state of overtourism in SITEs ( Cole, 2007 ; McElroy, 2006 ).

In comparison to nonsovereign Caribbean SITEs, sovereign Caribbean SITEs experience significantly higher levels of overtourism.

Cole (2007) indicates that an overshoot in Caribbean tourism arises from several interdependent factors, including growing tourism demand; surpassing physical limits of beachfront or coastal areas for resort construction; increasing labor migration due to limited local workforce; growing visitors' sense of overcrowding and an escalation in residents feeling overwhelmed or displaced by visitors and/or immigrant workers. The latter describes intensifying sentiments of visitor annoyance and apathy by local communities ( Doxey, 1978 ). The unfolding of these events triggers a spiral of demise where surging small island coastal tourism causes increasing crowding, congestion and contamination. Frequently, this leads to irreversible ecological destruction, social decay and aesthetic repulsion and a further uncontrolled spiraling effect ( Dehoorne et al. , 2010 ).

In addressing the dominance of political linkages in nonsovereign island economies ( Bertram, 2004 ) and the political economy of tourism development in small islands, several studies discuss the influence of (inter)institutional actors and networks of power and control that shape tourism policies and influence tourism developments adversely ( Baldacchino, 2006 ; Crandall, 1994 ; Duval, 2004 ; Bishop, 2010 ; Joppe, 2019 ; Richter, 1994 ). The political economy of Caribbean island tourism is oftentimes riddled by exclusion and extraction rather than inclusion and regeneration ( Bishop, 2010 ; Daye et al. , 2008 ; Duval, 2004 ; McElroy and Albuquerque, 2002 ). Crandall (1994) and Richter (1994) contend that these tensions stem from a combination of factors, including narrow and concentrated economic beneficiaries of tourism, land disputes, increasing public-sector infrastructure strains and taxes, rising costs of living, excessive migration with limited career opportunities and social dislocations. According to Baldacchino (2006) and Bertram (2004) , these features are closely intertwined with the political economy of nonsovereign island economies.

The confluence of these failures intensify the negative externalities due to several structural political economic conditions, including (1) a regulatory deficiency in environmental conservation and enforcement, (2) limited economic diversification and innovation, (3) lopsided (private) benefits and (public) costs of tourism growth, (4) marginal social inclusion and nongovernmental participation in tourism policy and development and (5) a strong and persistent bias toward short-term tourism promotion, expansion and growth ( Bishop, 2010 ; Cole, 2007 ; Daye et al. , 2008 ; Dodds and Butler, 2019b ; Joppe, 2019 ; McElroy, 2003 ). Moreover, Williams and Ponsford (2008) argue that politically-linked public institutions and agents tend to circumvent regulations and regulatory enforcement largely due to the economic “lock-in” of the tourism industry. Hall and Williams (2008) describe this tourism “lock-in” as path dependency, which is conducive to institutional failures (e.g. close personal and political ties and resource dependency), network failures (e.g. dissonance and ignorance of new developments) and capability failures (e.g. lack of institutional learning capabilities).

Higher levels of overtourism are associated with both international tourism demand as well as interdependent tourism supply factors.

In conclusion, whereas growing international tourism demand creates the conditions for overtourism, several interdependent domestic supply factors are regarded as the key determinants that drive overtourism ( Acevedo et al. , 2017 ; Bishop, 2010 ; Cole, 2007 ; Dodds and Butler, 2019b ; Duval, 2004 ; Joppe, 2019 ; Hall and Williams, 2008 ; McElroy, 2006 ; Richter, 1994 ; Williams and Ponsford, 2008 ). Overtourism is likely to ascend when both push and pull forces are mutually reinforcing, i.e. surging demand and expansionary supply. Consequently, the confluence and acceleration of multiple tourism demand and tourism supply forces shape the evolution of overtourism in Caribbean SITEs.

3. Research methodology

The aim of this exploratory study is to (1) investigate the status and qualities of overtourism in sovereign and nonsovereign Caribbean SITEs, and (2) examine the antecedents and effects of overtourism in mature SITEs. The two main research questions addressed are as follows: (1) how do sovereign and nonsovereign SITEs in the Caribbean differ? (2) what are the main drivers and impacts of overtourism in selected Caribbean SITEs?

3.1 Data compilation

Based on previous studies and available secondary historical data covering the years between 2000 and 2018 ( Caribbean Tourism Organization–CTO, 2020 ; United Nations World Tourism Organization–UNWTO, 2019 ; World Bank–WB, 2018 ; World Travel and Tourism Council–WTTC, 2019 ), sixteen (16) Caribbean SITEs were selected including both sovereign and nonsovereign SITEs (see Table 1 ). The sovereign SITEs comprise Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. The nonsovereign SITEs consist of Anguilla, Aruba, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Martinique, St. Maarten and the US Virgin Islands. Several Caribbean island tourism-dependent economies were excluded due to their relatively larger population size and land mass (e.g. Jamaica) or limited/incomplete data (e.g. Turks and Caicos). Previous studies indicate that both population size and land mass influence the shape and style of (over)tourism growth ( Briguglio et al. , 1996 ; Cole, 2007 ; McElroy, 2006 ). Likewise, this study acknowledges that Caribbean SITEs differ in their style and stage of tourism development, and in fact, a key element of interest in this study is whether sovereign and nonsovereign SITEs differ in any systematic manner.

Building forth on previous studies, the following indicators and measurements were used subject to the availability of sufficient and complete data. The overtourism construct is formed by a composite of three sub-indicators including tourism intensity (total visitors to population), tourism density (visitors per km 2 ) and tourism dependency (tourism exports to GDP) ( Cole, 2007 ; Dodds and Butler, 2019b ; McElroy, 2006 ). The tourism arrivals, cruise visitor, population and trade data were drawn from the tourism publications and databases of the CTO, 2020 , the UNWTO, 2019 , the World Bank ( WB, 2018 ) and the WTTC, 2019 and used to calculated to sub-indices of overtourism tourism intensity, tourism density and tourism dependency. To test for heteroskedasticity under assumption of nonlinearity, the White test was conducted with no significant effects (Chi-Square = 20; p > 0.05).

The dependent variables comprise the direct and indirect transmission channels of overtourism and are based on previously operationalized measurements by Capocchi et al. (2019) , Daye et al. (2008) , Dodds and Butler (2019b) , Duval (2004) , Gupta and Vegeling (2016) , Joppe (2019) , Koens et al. (2018) and McElroy (2003 , 2006 ). Data on economic growth, income inequality, labor force participation and environmental pollution data were compiled from several databases from the CTO (2019a, b) , the UNWTO (2019) and the WB (2018) .

Likewise, the variables describing international tourism demand and domestic tourism supply are based on previous tourism studies ( Acevedo et al. , 2017 ; Bishop, 2010 ; Cole, 2007 ; Dodds and Butler, 2019b ; Duval, 2004 ; Joppe, 2019 ; Hall and Williams, 2008 ; McElroy, 2006 ; Richter, 1994 ; Williams and Ponsford, 2008 ). Based on tourism data from the UNWTO (2018) , the WTTC (2019) and the WB (2018) , tourism demand and supply were measured by the relative destination market share of Caribbean tourism arrivals, amount of airlift, number of accommodations and the size of tourism labor force ( Acevedo et al. , 2017 ; Cole, 2007 ; McElroy, 2006 ; Richter, 1994 ). Furthermore, from an infrastructure perspective, the number and (spatial) concentration of cruise arrivals as well as resorts was measured. The number of rooms per resort was used as proxy measure for resort style ( McElroy, 2006 ). The degree of tourism export specialization was calculated by analyzing tourism receipts, the ratio of tourism exports to GDP and total imports and exports as percentage of GDP ( WTTC, 2019 ; WB, 2018 ).

3.2 Analyzing significant differences in overtourism

To identify the differentiating features of overtourism across sovereign and nonsovereign SITEs (see Proposition 3 ) and consistent with previous studies and measures ( McElroy, 2003 , 2006 ), the data were standardized across several indicators in order to normalize the data and facilitate comparative and inferential analyses. Available country data are standardized by using a min–max scaling method. The general formula for the min–max scaling (0, 1) is the following: y = ( x − min X ) ( max X − min X ) , where x is the original value, and y is the normalized value. For example, in terms of normalizing tourism intensity, the Cayman Islands received a standardized maximum score of 1 [(32–3)/(32–3)]. In similar fashion, the tourism density [(7,951–292)/(36,088–292)] and tourism dependency [(20–14)/(87–14)] scores are calculated and normalized. Subsequently, the normalized values of the different sub-indices are averaged to reach an overall composite overtourism index score. Due to data limitations and case sample constraints and based on previous studies ( Kinseng et al. , 2018 ), a nn-parametric test (Mann Whitney U test with Fisher exact significance test) was conducted to identify the significant differences between sovereign and nonsovereign Caribbean SITEs.

3.3 Analyzing regressors of overtourism

To explore the formative structure of the overtourism construct, in addition to reducing the number of individual variables and the potential multicollinearity, a principal component regression (PCR) analysis – a special form of partial least square regression – was applied ( Bair et al. , 2006 ), in which the formative overtourism construct was regressed on the newly identified components. The small case sample size and data limitations precluded the use of structural equation modeling or path analysis. In PCR and consistent with previous studies ( Li et al. , 2018 ), instead of regressing the dependent variable, i.e. overtourism, on all the explanatory variables directly, the principal components of the explanatory variables are used as regressors. In applying PCR, there are three basic steps ( Li et al. , 2018 ), i.e. to conduct a principal component analysis of the individual variables, identify the validity and reliability parameters of the principal components and run a stepwise multivariate regression analysis on the valid components to identify the significant regressors. In examining the main antecedents of overtourism (see Propositions 1 , 2 and 4 ), the applied PCR follows production-like logic consisting of the different identified principal regressors ( Du et al. , 2016 ). The production function form is estimated as a log-linear relationship using ln ( Y ) = a 0 + ∑ a i ln ( I i ) + ε , with Y = overtourism composite index, I = antecedent factors (i.e. the PCR predictors) and a = coefficients.

4.1 How do sovereign and nonsovereign SITEs in the caribbean differ?

In examining the proposition that sovereign Caribbean SITEs experience significantly higher levels of overtourism, the findings indicate that there are significant differences between sovereign and nonsovereign SITEs (see Table 2 ). Caribbean nonsovereignties experience higher levels of tourism intensity, density and dependency. Their trade openness and tourism specialization underscore a strong outward economic orientation, which is also corroborated by relatively more airlift and cruise calls. Demographically, nonsovereign SITEs have a larger migrant labor stock and population density ratio, largely due to tourism labor immigration and their sub-national jurisdictional status. Conversely, their coastal length is smaller with less coastal beach space. Consequently, coastal density levels for resorts, visitors and pollution are relatively greater in nonsovereign tourism dependencies. While not being significant, the cruise intensity and average resort size is slightly larger in nonsovereign SITEs due to the establishment of comparatively more international and larger resorts, as well as having more cruise calls.

In terms of climate change impact, nonsovereign SITEs are comparatively less prone to the costs of climate change when compared to sovereign SITEs. From a geopolitical perspective, nonsovereign SITEs may have access to finance and international assistance due to their subnational jurisdictional ties, and therefore more likely to absorb the costs of climate change ( Baldacchino, 2006 ; Bertram, 2004 ; McElroy and Pearce, 2006 ). Alternatively, nonsovereign SITEs may be geographically dispersed and positioned on the peripheral of the Caribbean Hurricane belt, thereby reducing the direct exposure, risks and costs of extreme weather events. This would nurture the relatively uninterrupted and continuous expansion and growth of tourism. The findings indicate that climate change and tourism density are indeed negatively associated ( β = −0.14; p < 0.05).

These results corroborate previous studies that nonsovereign Caribbean SITEs share a unique overtourism profile consisting of high tourism intensity, density and dependency levels; mature and expansive port and tourism infrastructures; large-scale beach front accommodations and international luxury chains; significant tourism promotion and tourism labor immigration and tourism-induced ecological stress with increasing social crowding especially in coastal zones ( Budowski, 1976 ; Butler, 1980 ; Cohen, 1978 ; Dodds and Butler, 2019b ; Doxey, 1978 ; Dunkel, 1984 ; Farrell and Runyan, 1991 ; Getz, 1983 ; Holder, 1988 ; Mathieson and Wall, 1982 ; McElroy, 2006 ; Wilkinson, 1989 ) .

4.2 What are the main antecedents and effects of overtourism in selected Caribbean SITEs?

An unrestrictive principal component analysis with Kaiser normalization and varimax rotation was conducted to identify the main constructs of overtourism. The analysis yielded five (5) components with satisfactory loadings (>0.60), acceptable adequacy (KMO > 0.68; Bartlett's test of sphericity < 0.001) and reliability (Cronbach α > 0.70) for an exploratory study (see Table 3 ). Consistent with previous studies ( Cole, 2007 ; Dodds and Butler, 2019b ; McElroy, 2006 ), the findings indicate that the status of overtourism component incorporates tourism intensity, tourism density and tourism dependency, reflecting the volume, concentration and contribution of tourism, respectively.

Based on the (unweighted) average of tourism intensity, density and dependency sub-indices, a general overtourism index was calculated (see Table 4 for sub-indices). The average overtourism index demonstrates that the propensity for overtourism is relatively higher in nonsovereign SITEs, i.e. St. Maarten, Aruba, Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands, Anguilla and the US Virgin Islands, which indeed share a unique and significantly different overtourism profile (Chi-square = 7.27 and p < 0.01), despite individual destination niche differences (see Table 4 ). These islands represent Dutch, British and US nonsovereign Caribbean SITEs. These results support the proposition that sovereign Caribbean SITEs experience significantly higher levels of overtourism.

Based on the results of the principal component analysis, three independent constructs – antecedents of overtourism – were identified, i.e. tourism supply chain, tourism architectural style and tourism export specialization. Whereas the tourism supply chain component describes the supply chain effect of the growth in airlift, accommodations and labor, the tourism infrastructure component describes the spatial concentration and design of cruise and accommodation infrastructures in a specific geographic area or coastal zone. The tourism export specialization component describes the outward (export-led) economic orientation and tourism specialization focused on, e.g. tourism investments and expansion, export earnings and revenues and promotion. The tourism ecological stress component consists of coastal resort stress, coastal visitor stress and coastal pollution and is an indirect effect of overtourism. It describes the stressors and pressures from land- and marine-based tourism activities in (concentrated) coastal areas, which are conducive to ecological decay and coastal erosion ( Duval, 2004 ; Ewing-Chow, 2019 ; Gossling, 2002 ; Hunter and Shaw, 2007 ; Marsiglio, 2018 ; McElroy, 2006 ; Williams and Ponsford, 2008 ).

The findings also indicated that several variables had insufficient factor loadings (<0.60) and were therefore disregarded and excluded from further analysis. These variables include relative tourism market share and population density and are both considered structural features of destination size ( McElroy, 2006 ).

To examine Proposition 1 , 2 , and 4 , regression analysis was conducted on the previously identified components to assess the relationship between the state of overtourism, tourism ecological stress and labor force participation. Due to the hypothesized nonlinear nature of tourism development ( Butler, 1980 ; Farrell and Twining-Ward, 2004 ), a quadratic multivariate regression analysis was applied. The findings (see Table 5 ) indicate that a quadratic function has superior fit ( F -test = 11.41 and p < 0.001) with an adjusted R 2 of 0.64 and a significant curve-linear relationship ( p < 0.01) between the state of overtourism and tourism ecological stress ( β 2 = 0.96 and β 1 = 0.02).

This concave relationship indicates that as the intensity and density of tourism increases, the ecological pressures grow and, more importantly, accelerate after exceeding a critical threshold, as measured by the inflection point. This underscores a tourism overshoot beyond the natural absorptive capacity of the local ecology, which generates negative pressures on real GDP growth in the long run. Furthermore, this adverse impact is compounded by the negative (nonlinear) effects of climate change ( β 2 = −0.75; adjusted R 2 = 0.28; p < 0.10) on the real output. These results provide support for proposition that higher levels of overtourism in Caribbean SITEs are positively associated with relatively more ecological stress ( Proposition 1 ).

In terms of the labor market impact, the results of the quadratic regression analysis indicate that overtourism has a negative (curve-linear) effect on labor force participation ( β 2 = −2.14; adjusted R 2 = 0.29; p < 0.05), which depicts a tourism overrun and exhaustion of the domestic labor market and tourism workforce capacity. Further analysis indicates that overtourism has a negative (curve-linear) effect on real GDP growth between 1995 and 2018 ( β 2 = −5.28; adjusted R 2 = 0.39; p < 0.05) and is a significant source of output volatility – as measured by the output variance – in selected Caribbean SITEs ( β = 0.84; adjusted R 2 = 0.23; p < 0.05). The results suggest that beyond a certain optimum state of tourism intensity, density and dependency, there is an exponentially adverse effect on the socioecology of selected Caribbean SITEs, including Anguilla, Aruba, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, St. Maarten and the US Virgin Islands. These findings provide support for proposition that higher levels of overtourism in Caribbean SITEs are positively associated with relatively lower labor force participation and higher economic volatility ( Proposition 1 ). Moreover, the results indicate that the impact of overtourism in Caribbean SITEs is transmitted through both direct as well as indirect channels ( Proposition 2 ).

Turning toward to the antecedents of overtourism (see Table 6 ), the results indicate that three supply-oriented components influence the state of overtourism (adjusted R 2 = 0.81; p < 0.05). A significant association is found for tourism supply chain ( β = 0.47; p < 0.01). Likewise, tourism infrastructure ( β = 0.30; p < 0.05) and tourism export specialization ( β = 0.25; p < 0.05) show significant positive relationships with the state of overtourism. From an international tourism demand-based perspective, the relative tourism market share (in the Caribbean) has a significant positive effect on the state of overtourism ( β = 0.26; p < 0.05). Although the tourism supply chain effect shows a relatively stronger association, the findings indicate that there is no single factor that determines the extent or state of overtourism. Rather, it is a combination of mutually reinforcing supply and demand conditions and the multiplicative forces that shape the state of overtourism in selected Caribbean SITEs. These results provide support for proposition that higher levels of overtourism in Caribbean SITEs are positively associated with both international tourism demand and supply factors ( Proposition 4 ).

5. Discussion

In reviewing the overall findings of this study, the general results corroborate previous research ( Acevedo et al. , 2017 ; Baldacchino, 2006 ; Bishop, 2010 ; Capocchi et al. , 2019 ; Dodds and Butler, 2019b ; Duval, 2004 ; Joppe, 2019 ; McElroy, 2006 ; Scheyvens and Biddulph, 2017 ; Richter, 1994 ; Williams and Ponsford, 2008 ) and support the research propositions (see Table 7 ). More specifically, the research indicates that there are significant differences between sovereign and nonsovereign SITEs in the Caribbean.

Nonsovereign SITEs are more likely to experience a higher propensity for overtourism and the adverse effects and risks thereof. Their longstanding outward economic growth orientation is geared at increasing tourism exports and fostering tourism investments, with a constant focus on expanding airlift, cruise calls and related tourism infrastructures and services. These progrowth tourism policies usually entail numerous fiscal and economic incentives, including e.g. tax holidays, government guarantees and special concessions for international tourism investors and contractors. Furthermore, the private tourism sector is actively involved in the shaping of tourism policies and is an (in)direct beneficiary of tourism (tax) revenues.

The tourism infrastructure in nonsovereign SITEs is mainly characterized by large scale and international chain resorts, which are mostly concentrated in coastal areas. In addition, nonsovereign SITEs enjoy frequent cruise calls and experience higher cruise intensity levels. Their past tourism achievements have been rewarded with numerous destination marketing and branding awards, and they enjoy a relatively popular reputation among visitors, which reinforces further tourism intensity and export specialization.

Their subsequent demographic development is characterized by a comparatively large migrant labor stock and high population density, mainly due to tourism labor immigration stemming primarily from the increasing specialization in and style of tourism. The confluence of these factors generates higher coastal density levels and environmental pollution in nonsovereign tourism dependencies. Although not immune to the gradual “slow-burn” effects of global warming and sea level rise, nonsovereign SITEs are also comparatively less prone to the costs of extreme weather events when compared to sovereign SITEs.