What Was the Age of Exploration?

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

- Key Figures & Milestones

- Physical Geography

- Political Geography

- Country Information

- Urban Geography

The Birth of the Age of Exploration

The discovery of the new world, opening the americas, the end of the era, contributions to science, long-term impact.

- M.A., Geography, California State University - East Bay

- B.A., English and Geography, California State University - Sacramento

The era known as the Age of Exploration, sometimes called the Age of Discovery, officially began in the early 15th century and lasted through the 17th century. The period is characterized as a time when Europeans began exploring the world by sea in search of new trading routes, wealth, and knowledge.

During this era, explorers learned more about areas such as Africa and the Americas and brought that knowledge back to Europe. Massive wealth accrued to European colonizers due to trade in goods, spices, and precious metals. Nevertheless, there were also vast consequences. Labor became increasingly important to support the massive plantations in the New World, leading to the trade of enslaved people, which lasted for 300 years and had an enormous impact on Africa and North America.

The impact of the Age of Exploration would permanently alter the world and transform geography into the modern science it is today.

Key Takeaways

- During the Age of Exploration, methods of navigation and mapping improved, switching from traditional portolan charts to the world's first nautical maps; the colonies and Europe also exchanged new food, plants, and animals.

- The Age of Exploration also decimated indigenous communities due to the combined impact of disease, overwork, and massacres.

- The impact persists today, with many of the world's former colonies still considered the developing world, while colonizing countries are the First World countries, holding a majority of the world's wealth and annual income.

Many nations were looking for goods such as silver and gold, but one of the biggest reasons for exploration was the desire to find a new route for the spice and silk trades.

When the Ottoman Empire took control of Constantinople in 1453, it blocked European access to the area, severely limiting trade. In addition, it also blocked access to North Africa and the Red Sea, two very important trade routes to the Far East.

The first of the journeys associated with the Age of Discovery were conducted by the Portuguese. Although the Portuguese, Spanish, Italians, and others had been plying the Mediterranean for generations, most sailors kept well within sight of land or traveled known routes between ports. Prince Henry the Navigator changed that, encouraging explorers to sail beyond the mapped routes and discover new trade routes to West Africa.

Portuguese explorers discovered the Madeira Islands in 1419 and the Azores in 1427. Over the coming decades, they would push farther south along the African coast, reaching the coast of present-day Senegal by the 1440s and the Cape of Good Hope by 1490. Less than a decade later, in 1498, Vasco da Gama would follow this route to India.

While the Portuguese were opening new sea routes along Africa, the Spanish also dreamed of finding new trade routes to the Far East. Christopher Columbus , an Italian working for the Spanish monarchy, made his first journey in 1492. Instead of reaching India, Columbus found the island of San Salvador in what is known today as the Bahamas. He also explored the island of Hispaniola, home of modern-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Columbus would lead three more voyages to the Caribbean, exploring parts of Cuba and the Central American coast. The Portuguese also reached the New World when explorer Pedro Alvares Cabral explored Brazil, setting off a conflict between Spain and Portugal over the newly claimed lands. As a result, the Treaty of Tordesillas officially divided the world in half in 1494.

Columbus' journeys opened the door for the Spanish conquest of the Americas. During the next century, men such as Hernan Cortes and Francisco Pizarro would decimate the Aztecs of Mexico, the Incas of Peru, and other indigenous peoples of the Americas. By the end of the Age of Exploration, Spain would rule from the Southwestern United States to the southernmost reaches of Chile and Argentina.

Great Britain and France also began seeking new trade routes and lands across the ocean. In 1497, John Cabot , an Italian explorer working for the English, reached what is believed to be the coast of Newfoundland. Many French and English explorers followed, including Giovanni da Verrazano, who discovered the entrance to the Hudson River in 1524, and Henry Hudson, who mapped the island of Manhattan first in 1609.

Over the next decades, the French, Dutch, and British would all vie for dominance. England established the first permanent colony in North America at Jamestown, Va., in 1607. Samuel du Champlain founded Quebec City in 1608, and Holland established a trading outpost in present-day New York City in 1624.

Other important voyages of exploration during this era included Ferdinand Magellan's attempted circumnavigation of the globe, the search for a trade route to Asia through the Northwest Passage , and Captain James Cook's voyages that allowed him to map various areas and travel as far as Alaska.

The Age of Exploration ended in the early 17th century after technological advancements and increased knowledge of the world allowed Europeans to travel easily across the globe by sea. The creation of permanent settlements and colonies created a network of communication and trade, therefore ending the need to search for new routes.

It is important to note that exploration did not cease entirely at this time. Eastern Australia was not officially claimed for Britain by Capt. James Cook until 1770, while much of the Arctic and Antarctic were not explored until the 20th century. Much of Africa also was unexplored by Westerners until the late 19th century and early 20th century.

The Age of Exploration had a significant impact on geography. By traveling to different regions around the globe, explorers were able to learn more about areas such as Africa and the Americas and bring that knowledge back to Europe.

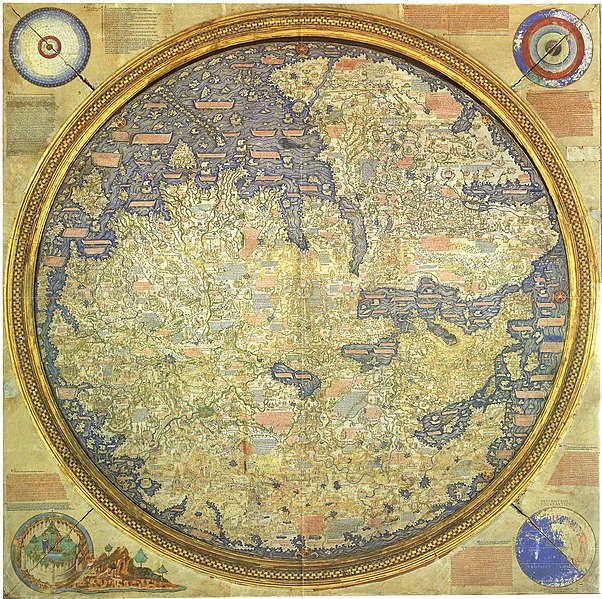

Methods of navigation and mapping improved as a result of the travels of people such as Prince Henry the Navigator. Before his expeditions, navigators had used traditional portolan charts, which were based on coastlines and ports of call, keeping sailors close to shore.

The Spanish and Portuguese explorers who journeyed into the unknown created the world's first nautical maps, delineating not just the geography of the lands they found but also the seaward routes and ocean currents that led them there. As technology advanced and known territory expanded, maps and mapmaking became more and more sophisticated.

These explorations also introduced a whole new world of flora and fauna to Europeans. Corn, now a staple of much of the world's diet, was unknown to Westerners until the time of the Spanish conquest, as were sweet potatoes and peanuts. Likewise, Europeans had never seen turkeys, llamas, or squirrels before setting foot in the Americas.

The Age of Exploration served as a stepping stone for geographic knowledge. It allowed more people to see and study various areas around the world, which increased geographic study, giving us the basis for much of the knowledge we have today.

The effects of colonization persist as well, with many of the world's former colonies still considered the developing world and the colonizing nations the First World countries, which hold a majority of the world's wealth and receive a majority of its annual income.

- Profile of Prince Henry the Navigator

- The History of Cartography

- The Rise of Islamic Geography in the Middle Ages

- Brief History and Geography of Tibet

- Prester John

- Biography of Robert Cavelier de la Salle, French Explorer

- Captain James Cook

- Istanbul Was Once Constantinople

- Biography of Explorer Cheng Ho

- Ellen Churchill Semple

- Biography of Ferdinand Magellan, Explorer Circumnavigated the Earth

- Carl Ritter

- 18th Century Grand Tour of Europe

- What Is Mackinder's Heartland Theory?

- Biography of Abraham Ortelius, Flemish Cartographer

- Important Cities in Black History

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Europe and the age of exploration.

Salvator Mundi

Albrecht Dürer

The Celestial Map- Northern Hemisphere

Astronomical table clock

Astronomicum Caesareum

Michael Ostendorfer

Mirror clock

Movement attributed to Master CR

Portable diptych sundial

Hans Tröschel the Elder

Celestial globe with clockwork

Gerhard Emmoser

The Celestial Globe-Southern Hemisphere

James Voorhies Department of European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2002

Artistic Encounters between Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas The great period of discovery from the latter half of the fifteenth through the sixteenth century is generally referred to as the Age of Exploration. It is exemplified by the Genoese navigator, Christopher Columbus (1451–1506), who undertook a voyage to the New World under the auspices of the Spanish monarchs, Isabella I of Castile (r. 1474–1504) and Ferdinand II of Aragon (r. 1479–1516). The Museum’s jerkin ( 26.196 ) and helmet ( 32.132 ) beautifully represent the type of clothing worn by the people of Spain during this period. The age is also recognized for the first English voyage around the world by Sir Francis Drake (ca. 1540–1596), who claimed the San Francisco Bay for Queen Elizabeth ; Vasco da Gama’s (ca. 1460–1524) voyage to India , making the Portuguese the first Europeans to sail to that country and leading to the exploration of the west coast of Africa; Bartolomeu Dias’ (ca. 1450–1500) discovery of the Cape of Good Hope; and Ferdinand Magellan’s (1480–1521) determined voyage to find a route through the Americas to the east, which ultimately led to discovery of the passage known today as the Strait of Magellan.

To learn more about the impact on the arts of contact between Europeans, Africans, and Indians, see The Portuguese in Africa, 1415–1600 , Afro-Portuguese Ivories , African Christianity in Kongo , African Christianity in Ethiopia , The Art of the Mughals before 1600 , and the Visual Culture of the Atlantic World .

Scientific Advancements and the Arts in Europe In addition to the discovery and colonization of far off lands, these years were filled with major advances in cartography and navigational instruments, as well as in the study of anatomy and optics. The visual arts responded to scientific and technological developments with new ideas about the representation of man and his place in the world. For example, the formulation of the laws governing linear perspective by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) in the early fifteenth century, along with theories about idealized proportions of the human form, influenced artists such as Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). Masters of illusionistic technique, Leonardo and Dürer created powerfully realistic images of corporeal forms by delicately rendering tendons, skin tissues, muscles, and bones, all of which demonstrate expertly refined anatomical understanding. Dürer’s unfinished Salvator Mundi ( 32.100.64 ), begun about 1505, provides a unique opportunity to see the artist’s underdrawing and, in the beautifully rendered sphere of the earth in Christ’s left hand, metaphorically suggests the connection of sacred art and the realms of science and geography.

Although the Museum does not have objects from this period specifically made for navigational purposes, its collection of superb instruments and clocks reflects the advancements in technology and interest in astronomy of the time, for instance Petrus Apianus’ Astronomicum Caesareum ( 25.17 ). This extraordinary Renaissance book contains equatoria supplied with paper volvelles, or rotating dials, that can be used for calculating positions of the planets on any given date as seen from a given terrestrial location. The celestial globe with clockwork ( 17.190.636 ) is another magnificent example of an aid for predicting astronomical events, in this case the location of stars as seen from a given place on earth at a given time and date. The globe also illustrates the sun’s apparent movement through the constellations of the zodiac.

Portable devices were also made for determining the time in a specific latitude. During the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, the combination of compass and sundial became an aid for travelers. The ivory diptych sundial was a specialty of manufacturers in Nuremberg. The Museum’s example ( 03.21.38 ) features a multiplicity of functions that include giving the time in several systems of counting daylight hours, converting hours read by moonlight into sundial hours, predicting the nights that would be illuminated by the moon, and determining the dates of the movable feasts. It also has a small opening for inserting a weather vane in order to determine the direction of the wind, a feature useful for navigators. However, its primary use would have been meteorological.

Voorhies, James. “Europe and the Age of Exploration.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/expl/hd_expl.htm (October 2002)

Further Reading

Levenson, Jay A., ed. Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration . Exhibition catalogue. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1991.

Vezzosi, Alessandro. Leonardo da Vinci: The Mind of the Renaissance . New York: Abrams, 1997.

Additional Essays by James Voorhies

- Voorhies, James. “ Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) and the Spanish Enlightenment .” (October 2003)

- Voorhies, James. “ Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ School of Paris .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Art of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries in Naples .” (October 2003)

- Voorhies, James. “ Elizabethan England .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and His Circle .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Fontainebleau .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Post-Impressionism .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Domestic Art in Renaissance Italy .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Surrealism .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- Collecting for the Kunstkammer

- East and West: Chinese Export Porcelain

- European Exploration of the Pacific, 1600–1800

- The Portuguese in Africa, 1415–1600

- Trade Relations among European and African Nations

- Abraham and David Roentgen

- African Christianity in Ethiopia

- African Influences in Modern Art

- Anatomy in the Renaissance

- Arts of the Mission Schools in Mexico

- Astronomy and Astrology in the Medieval Islamic World

- Birds of the Andes

- Dualism in Andean Art

- European Clocks in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries

- Gold of the Indies

- The Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburgs, 1400–1600

- Islamic Art and Culture: The Venetian Perspective

- Ivory and Boxwood Carvings, 1450–1800

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)

- The Manila Galleon Trade (1565–1815)

- Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art

- Polychrome Sculpture in Spanish America

- The Solomon Islands

- Talavera de Puebla

- Venice and the Islamic World: Commercial Exchange, Diplomacy, and Religious Difference

- Visual Culture of the Atlantic World

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1400–1600 A.D.

- Florence and Central Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- 15th Century A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- Architecture

- Astronomy / Astrology

- Cartography

- Central America

- Central Europe

- Colonial American Art

- Colonial Latin American Art

- European Decorative Arts

- Great Britain and Ireland

- Guinea Coast

- Iberian Peninsula

- Mesoamerican Art

- North America

- Printmaking

- Renaissance Art

- Scientific Instrument

- South America

- Southeast Asia

- Western Africa

- Western North Africa (The Maghrib)

Artist or Maker

- Apianus, Petrus

- Bos, Cornelis

- Dürer, Albrecht

- Emmoser, Gerhard

- Gevers, Johann Valentin

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Ostendorfer, Michael

- Troschel, Hans, the Elder

- Zündt, Matthias

Online Features

- 82nd & Fifth: “Celestial” by Clare Vincent

- MetCollects: “ Ceremonial ewer “

The Ages of Exploration

Age of discovery, age of discovery.

15th century to the early 17th century

The Age of Discovery refers to a period in European history in which several extensive overseas exploration journeys took place. Religion, scientific and cultural curiosity, economics, imperial dominance, and riches were all reasons behind this transformative age. The search for a westward trade route to Asia was one of the largest motivations for many of these voyages. Christopher Columbus’ voyage across the Atlantic Ocean in 1492 lead to the discovery of a New World, and created a new surge in exploration and colonization. World maps changed as European powers such as England, France, Spain, the Dutch, and Portugal began claiming lands. But there were also negative effects to the Europeans’ arrival in the New World. Europeans encountered, and in many cases conquered and enslaved, native peoples of the new lands to which they traveled.

Advancements in ships, navigational instruments, and knowledge of world geography grew significantly. Vessels of the Age of Discovery continued to be built of wood and powered by sail or oar, and, on occasion, both. Medieval navigational tools such as the compass, kamal, astrolabe, cross-staff, and the mariner’s quadrant were still used but became replaced by more effective tools. Newer tools such as the mariner’s astrolabe, traverse board, and back staff soon provided better navigational support in determining longitude and latitude. These tools, along with improved maps enabled explorers to travel the vast oceans as never before. The Age of Discovery created a new period of global interaction, and began a new age of European colonialism that would intensify over the next several centuries.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

European History/Exploration and Discovery

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Causes of the Age of Exploration

- 3 Portuguese Roles in Early Exploration

- 4.1 Prince Henry (1394–1460)

- 4.2 Bartolomeu Dias (1450-1500)

- 4.3 Vasco da Gama (1460–1524)

- 4.4 Pedro Álvares Cabral (1467–1520)

- 4.5 Ferdinand Magellan (1480–1521)

- 4.6 Francis Xavier (1506 –1552)

- 5.1 Francisco Pizarro (1529-1541)

- 5.2 Christopher Columbus (1451-1506)

- 5.3 Ferdinand Magellan (1480-1521)

- 5.4 Vasco Nuñez de Balboa (1475-1519)

- 5.5 Hernando Cortés (1485-1547)

- 5.6 Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1566)

- 5.7 Juan Ponce de León (1474-1521)

- 6.1 Sir Francis Drake (1540-1596)

- 6.2 John Cabot (1450-1499)

- 7.1 Rene-Robert de La Salle

- 7.2 Father Jacques Marquette

- 7.3 Louis Jolliet

- 7.4 Jacques Cartier (1491-1551)

- 7.5 Samuel de Champlain (1567-1635)

- 8.1 Willem Barentsz (1550-1597)

- 8.2 Henry Hudson (1565-1611)

- 8.3 Willem Janszoon (1571-1638)

- 8.4 Abel Tasman (1603-1659)

- 9 Results of the Age of Exploration

Introduction

During the fifteenth and the sixteenth century the states of Europe began their modern exploration of the world with a series of sea voyages. The Atlantic states of Spain and Portugal were foremost in this enterprise though other countries, notably England and the Netherlands, also took part.

These explorations increased European knowledge of the wider world, particularly in relation to sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas . These explorations were frequently connected to conquest and missionary work, as the states of Europe attempted to increase their influence, both in political and religious terms, throughout the world.

Causes of the Age of Exploration

The explorers of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries had a variety of motivations, but were frequently motivated by the prospects of trade and wealth. The earliest explorations, round the coast of West Africa , were designed to bypass the trade routes that brought gold across the Sahara Desert . The improved naval techniques that developed then allowed Europeans to travel further afield, to India and, ultimately, to the Americas.

The early explorations of Spain and Portugal were particularly aided by new ship designs. Prior to the fifteenth century Spain and Portugal largely relied on a ship known as the galley . Although galleys were fast and manoeuvrable, they were designed for use in the confined waters of the Mediterranean, and were unstable and inefficient in the open ocean. To cope with oceanic voyages, European sailors adapted a ship known as the cog , largely used in the Baltic and North Sea , which they improved by adding sail designs used in the Islamic world. These new ships, known as caravels , had deep keels, which gave them stability, combined with lateen sails , which allowed them to best exploit oceanic winds.

The astrolabe was a new navigational instrument in Europe that borrowed from the Islamic world, which used it in deserts. Using coordinates via the sky, one rotation of the astrolabe's plate, called a tympan , represented the passage of one day, allowing sailors to approximate the time, direction in which they were sailing, and the number of days passed. The astrolabe was replaced by the sextant as the chief navigational instrument in the 18th century. The sextant measured celestial objects in relation to the horizon, as opposed to measuring them in relation to the instrument. As a result, explorers were now able to sight the sun at noon and determine their latitude, which made this instrument more accurate than the astrolabe.

Portuguese Roles in Early Exploration

In 1415, the Portuguese established a claim to some cities (Ceuta, Tangiers) on what is today the Kingdom of Morocco , and in 1433 they began the systematic exploration of the west African coast. In August 1492, Christopher Columbus , whose nationality is still today subject to much debate, set sail on behalf of Ferdinand and Isabella whose marriage had united their crowns forming what is still today the Kingdom of Spain, and on October 12 of that same year, he eventually reached the Bahamas thinking it was the East Indies . In his mind he had reached the eastern end of the rich lands of India and China described in the thirteenth century by the Venetian explorer Marco Polo.

As a result, a race for more land, especially in the so-called "East Indies" arose. In 1481, a papal decree granted all land south of the Canary Islands to Portugal, however, and the areas explored by Columbus were thus Portuguese territories. In 1493, the Spanish-descendant Pope Alexander VI , declared that all lands west of the longitude of the Cape Verde Islands should belong to Spain while new lands discovered east of that line would belong to Portugal. These events led to increasing tension between the two powers given the fact that the king of Portugal saw the role of Pope Alexander VI Borgia as biased towards Spain. His role in the matter is still today a matter of strong controversy between European historians of that period.

The resolution to this occurred in 1494 at the Treaty of Tordesillas , creating, after long and tense diplomatic negotiations between the Kingdoms of Spain and Portugal, a dividing line 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands. Portugal received the west African Coast and the Indian Ocean route to India, as well as part of the Pacific Ocean waterways, while Spain gained the Western Atlantic Ocean and the lands further to the west. «Unknowingly», Portugal received Brazil. King John II of Portugal, however, seems to have had prior knowledge of the location of that Brazilian territory, for in the difficult negotiations of the Treaty of Tordesillas he managed, in a move still open for debate amongst historians of the period today, to push the dividing line further to the west, making it possible to celebrate the official discovery of Brazil and the reclaiming of the land only in 1500, already under the auspices of the treaty.

Important Portuguese Explorers

Prince henry (1394–1460).

Prince Henry "the Navigator" financially supported various voyages. He created a school for the advancement of navigation, laying the groundwork for Portugal to become a leader in the Age of Exploration.

Bartolomeu Dias (1450-1500)

Bartolomeu Dias , the first European to sail around the Cape of Good Hope , also found that India was reachable by sailing around the coast of the continent. As a result, trade with Asia and India was made considerably easier because travellers would no longer have to travel through the Middle East. Thus, there was a rise in Atlantic trading countries and a decline in Middle East and Mediterranean countries.

Vasco da Gama (1460–1524)

Vasco da Gama was the first to successfully sail directly from Europe to India in 1498. This was an important step for Europe because it created a sea route from Europe that would allow trade with the Far East instead of using the Silk Road Caravan route .

Pedro Álvares Cabral (1467–1520)

On April 21, 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral accidentally discovered Brazil while seeking a western route to the Indies. He first landed in modern-day Bahia.

Ferdinand Magellan (1480–1521)

Magellan was a Portuguese explorer sailing in a Spanish expedition, and was the first person to sail the Pacific Ocean and around South America. He attempted to circumnavigate the globe but died in the Philippines, although his crew successfully completed the voyage. One of his ships led by Juan Sebastian Elcano, who took over after Magellan died, made all the way around the globe!

Francis Xavier (1506 –1552)

Francis Xavier was a Spanish missionary, born in the castle of Xavier, a village near the city of Pamplona, from where he has his name. He was a member of the nobility and during his student years in Paris he became friends with Ignacio de Loiola with whom he would found the Jesuit Order He travelled extensively around Africa, India, the South Pacific, and even Japan and China.

Early Spanish Explorers

There were a number of other important explorers that were involved in the Age of Exploration.

Francisco Pizarro (1529-1541)

Pizarro was a Spanish explorer who militarily fought and conquered the Incan people and culture, claiming most of South America for Spain. He gained immense gold and riches for Spain from the defeat of the Incan empire.

Christopher Columbus (1451-1506)

Columbus , an explorer thought to be of Genoa (Italy), who after many unsuccessful attempts at finding patronship, explored the possibility of a western passage to the East Indies for the Spanish crown. Due to miscalculations on the circumference of the world Columbus did not account for the possibility of another series of continents between Europe and Asia, Columbus discovered the Caribbean in 1492. He introduced Spanish trade with the Americas which allowed for an exchange of cultures, diseases and trade goods, known as The Grand Exchange , whose consequences, good and bad, are still being experienced today.

Ferdinand Magellan (1480-1521)

Magellan was a Portuguese explorer who served the King of Spain, and was the first person to sail the Pacific Ocean and around South America. He attempted to be the first to circumnavigate the globe but was killed in the Philippines. His crew managed to successfully complete the voyage under the leadership of the Spanish Juan Sebastian del Cano. His parents had died when he was ten years old and he was sent to Lisbon in Portugal when he was twelve.

Vasco Nuñez de Balboa (1475-1519)

Balboa was a Spanish conquistador who founded the colony of Darién in Panama. He was the first to see the Pacific Ocean from America, and he settled much of the island of Hispaniola .

Hernando Cortés (1485-1547)

Cortés was a Spanish conquistador who assembled an army from the Spanish Colonies consisting of 600 men, 15 horsemen and 15 cannons. Using the assistance of a translator, Doña Marina , he assembled alliances with discontented subdued tribes in the Aztec empire. Through decisive use of superior weapons and native assistance, also the help of European disease which had already wrecked native populations, successfully conquered the Aztecs capturing Montezuma II , the current emperor, the city of Tenochtitlan and looting large amounts of Aztec gold.

Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1566)

Las Casas was a Spanish priest who advocated civil rights for Native Americans and strongly protested the way they were enslaved and badly treated. He wrote A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies and De thesauris in Peru .

Juan Ponce de León (1474-1521)

Juan Ponce de León was a Spanish conquistador hailing from Valladolid, Spain. He had served as the Governor of Puerto Rico when he started his own expedition in 1513, discovering Florida on March 27 of the same year and reaching its eastern coast on April 2. He called the land Florida (Spanish for flowery), either because of the vegetation he saw there, or it was Easter (Spanish: Pascua Florida ) that time. De Leon then organized subsequent voyages to Florida; the last one occurring in 1521 when he died.

English Explorers

Sir francis drake (1540-1596).

Sir Francis Drake was a letter of marque, one who is a privateer, for Britain during the time of Queen Elizabeth I . Though he is most remembered for helping command the English fleet against the Spanish Armada , he also spent many years in the Caribbean and successfully circumnavigated the world between 1577-1580.

John Cabot (1450-1499)

John Cabot, originally Giovanni Caboto was born in Genoa, Italy.

French Explorers

Rene-robert de la salle.

LaSalle was born in Rouen, France. He originally studied to be a Jesuit, but left the school to find adventure. He sailed to a French colony in Canada and became a fur trader. Indians told him of two great rivers (the Mississippi and Ohio). He made several explorations of them. He died when his men revelled in about 1687.

Father Jacques Marquette

Marquette was born in Laon, France, in the summer of 1637. He joined the Jesuits at age seventeen. The Jesuits told him to go be a missionary in Quebec. He founded missions all over the place. He explored many rivers. He died, age 38.

Louis Jolliet

Jolliet was born in a settlement near Quebec City. He was going to be a Jesuit priest, but abandoned these plans. He explored many rivers with Marquette. His place and date of death is unknown.

Jacques Cartier (1491-1551)

Jacques Cartier was an explorer who claimed Canada for France. He was born in Saint Malo, France in 1491. He was also the first European, not just the first Frenchman to describe and chart Saint Lawrence River and Gulf of Saint Lawrence. He made three important voyages. He died in Saint Malo, in 1551, aged 65.

Samuel de Champlain (1567-1635)

Samuel de Champlain was the "Father of New France". Founded Quebec City and today Lake Champlain is named in his honor.

Dutch Explorers

In the late 16th century Dutch explorers began to head out all over the world.

Willem Barentsz (1550-1597)

On June 5, 1594 Barentsz left the island of Texel aboard the small ship Mercury, as part of a group of three ships sent out in separate directions to try and enter the Kara Sea, with the hopes of finding the Northeast passage above Siberia. During this journey he discovered what is today Bjørnøya, also known as Bear Island.

Later in the journey, Barentsz reached the west coast of Novaya Zemlya, and followed it northward before being forced to turn back in the face of large icebergs. Although they did not reach their ultimate goal, the trip was considered a success.

Setting out on June 2, 1595, the voyage went between the Siberian coast and Vaygach Island. On August 30, the party came across approximately 20 Samoyed "wilde men" with whom they were able to speak, due to a crewmember speaking their language. September 4 saw a small crew sent to States Island to search for a type of crystal that had been noticed earlier. The party was attacked by a polar bear, and two sailors were killed.

Eventually, the expedition turned back upon discovering that unexpected weather had left the Kara Sea frozen. This expedition was largely considered to be a failure.

In May 1596, he set off once again, returning to Bear Island. Barentsz reached Novaya Zemlya on July 17. Anxious to avoid becoming entrapped in the surrounding ice, he intended to head for the Vaigatch Strait, but became stuck within the many icebergs and floes. Stranded, the 16-man crew was forced to spend the winter on the ice, along with their young cabin boy.

Proving successful at hunting, the group caught 26 Arctic foxes in primitive traps, as well as killing a number of polar bears. When June arrived, and the ice had still not loosened its grip on the ship, the scurvy-ridden survivors took two small boats out into the sea on June 13. Barentsz died while studying charts only seven days after starting out, but it took seven more weeks for the boats to reach Kola where they were rescued.

Henry Hudson (1565-1611)

In 1609, Hudson was chosen by the Dutch East India Company to find an easterly passage to Asia. He was told to sail around the Arctic Ocean north of Russia, into the Pacific and to the Far East. Hudson could not continue his voyage due to the ice that had plagued his previous voyages, and many others before him. Having heard rumors by way of Jamestown and John Smith, he and his crew decided to try to seek out a Southwest Passage through North America.

After crossing the Atlantic Ocean, his ship, the Halve Maen (Half Moon), sailed around briefly in the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays, but Hudson concluded that these waterways did not lead to the Pacific.

He then sailed up to the river that today bears his name, the Hudson River. He made it as far as present-day Albany, New York, where the river narrows, before he was forced to turn around, realizing that it was not the Southwest Passage.

Along the way, Hudson traded with numerous native tribes and obtained different shells, beads and furs. His voyage established Dutch claims to the region and the fur trade that prospered there. New Amsterdam in Manhattan became the capital of New Netherland in 1625

Willem Janszoon (1571-1638)

Early in Willem's life,1601 and 1602, he set out on two trips to the Dutch possessions in the East Indies. On November 18, 1605, he sailed from Bantam to the coast of western New Guinea. He then crossed the eastern end of the Arafura Sea, without seeing the Torres Strait, into the Gulf of Carpentaria, and on February 26, 1606 made landfall at the Pennefather River on the western shore of Cape York in Queensland, near the modern town of Weipa. This is the first recorded European landfall on the Australian continent. Willem Janszoon proceeded to chart some 320 km of the coastline, which he thought to be a southerly extension of New Guinea.

Willem Janszoon returned to the Netherlands in the belief that the south coast of New Guinea was joined to the land along which he coasted, and Dutch maps reproduced this error for many years to come.

Janszoon reported that on July 31, 1618 he had landed on an island at 22° South with a length of 22 miles and 240 miles SSE of the Sunda Strait. This is generally interpreted as a description of the peninsula from Point Cloate to North West Cape on the Western Australian coast, which Janszoon presumed was an island without fully circumnavigating it.

Abel Tasman (1603-1659)

In 1634 Tasman was sent as second in command of an exploring expedition in the north Pacific. His fleet included the ships Heemskerck and Zeehaen. After many hardships Formosa (now Taiwan) was reached in November, 40 out of the crew of 90 having died. Other voyages followed, to Japan in 1640 and 1641 and to Palembang in the south of Sumatra in 1642, where he made a friendly trading treaty with the Sultan. In August 1642 Tasman was sent in command of an expedition for the discovery of the "Unknown Southland", which was believed to be in the south Pacific but which had not been seen by Europeans

On November 24, 1642 Tasman sighted the west coast of Tasmania near Macquarie Harbour. He named his discovery Van Diemen's Land after Anthony van Diemen, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies. Proceeding south he skirted the southern end of Tasmania and turned north-east until he was off Cape Frederick Hendrick on the Forestier Peninsula. An attempt at landing was made but the sea was too rough; however, the carpenter swam through the surf, and, planting a flag, Tasman claimed formal possession of the land on December 3, 1642.

Tasman had intended to proceed in a northerly direction but as the wind was unfavourable he steered east. On December 13 they sighted land on the north-west coast of the South Island, New Zealand. After some exploration he sailed further east, and nine days later was the first European known to sight New Zealand, which he named Staten Landt on the assumption that it was connected to an island (Staten Island, Argentina) at the south of the tip of South America. Proceeding north and then east one of his boats was attacked by Māori in waka, and four of his men were killed.

En route back to Batavia, Tasman came across the Tongan archipelago on January 21, 1643. While passing the Fiji Islands Tasman's ships came close to being wrecked on the dangerous reefs of the north-eastern part of the Fiji group. He charted the eastern tip of Vanua Levu and Cikobia before making his way back into the open sea. He eventually turned north-west to New Guinea, and arrived at Batavia on June 15, 1643.

With three ships on his second voyage (Limmen, Zeemeeuw and the tender Braek) in 1644, he followed the south coast of New Guinea eastward. He missed the Torres Strait between New Guinea and Australia, and continued his voyage along the Australian coast. He mapped the north coast of Australia making observations on the land and its people.

From the point of view of the Dutch East India Company Tasman's explorations were a disappointment: he had neither found a promising area for trade nor a useful new shipping route. For over a century, until the era of James Cook, Tasmania and New Zealand were not visited by Europeans - mainland Australia was visited, but usually only by accident

Results of the Age of Exploration

The Age of Exploration led, directly to new communication and trade routes being established and the first truly global businesses to be established. Tea, several exotic fruits and new technologies were also introduced into Europe.

It also led to the decimation and extinction of Natives in other nations due to European diseases and poor working conditions. It also led indirectly to an increase in slavery (which was already widely practised throughout the world), as the explorations led to a rise in supply and thus demand for cotton , indigo , and tobacco .

Finally, as a result of the Age of Exploration, Spain dominated the end of the sixteenth century. The Age of Exploration provided the foundation for the European political and commercial worldwide imperialism of the late 1800s. From 1580 to 1640 Spain would inherit the right to reign over Portugal, whose interests where now in the hands of its political and geographical neighbour. Spain's power, under Spanish leader Philip II , was bigger than ever before and renewed and financed the power of the Papacy to fight against Protestant Reformation. However, in the seventeenth century, as the explorations were coming to an end and money was becoming scarcer, other countries began to openly challenge the spirit of the Tordesilas treaty and the power of Spain, which began to lapse and lose its former power.

European History 01. Background • 02. Middle Ages • 03. Renaissance • 04. Exploration • 05. Reformation 06. Religious War • 07. Absolutism • 08. Enlightenment • 09. French Revolution • 10. Napoleon 11. Age of Revolutions • 12. Imperialism • 13. World War I • 14. 1918 to 1945 • 15. 1945 to Present Glossary • Outline • Authors • Bibliography

- Book:European History

- Pages semi-protected against vandalism

Navigation menu

Brewminate: A Bold Blend of News and Ideas

Causes and Impacts of the European Age of Exploration

Share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

A time when Europe was swept up in the Renaissance and the Reformation, other major changes were taking place in the world.

Introduction

With today’s global positioning satellites, Internet maps, cell phones, and superfast travel, it is hard to imagine exactly how it might have felt to embark on a voyage across an unknown ocean. What lay across the ocean? In the early 1400s in Europe, few people knew. How long would it take to get there? That depended on the wind, the weather, and the distance. Days would have run together, with no sounds but the voices of the captain and the crew, the creaking of the sails, the blowing wind, and the splash of waves against the ship’s hull.

Would you be willing to undertake such a voyage? Only those most adventurous, most daring, and most confident in their abilities to sail in any weather, manage any crew, and meet any circumstance dared do so. They sailed west from England, Spain, and Portugal to North America. They sailed south from Portugal and Spain to South America, to lands where the Incas lived. They traveled to Africa, past the kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai. The crew of one Portuguese expedition even sailed completely around the world.

European explorers changed the world in many dramatic ways. Because of them, cultures divided by 3,000 miles or more of water began interacting. European countries claimed large parts of the world. As nations competed for territory, Europe had an enormous impact on people living in distant lands.

The Americas, in turn, made important contributions to Europe and the rest of the world. For example, from the Americas came crops such as corn and potatoes, which grew well in Europe. By increasing Europe’s food supply, these crops helped create population growth.

Another great change during the early modern age was the Scientific Revolution. Between 1500 and 1700, scientists used observation and experiments to make dramatic discoveries. For example, Isaac Newton formulated the laws of gravity. The Scientific Revolution also led to the invention of new tools, such as the microscope and the thermometer.

Advances in science helped pave the way for a period called the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment began in the late 1600s. Enlightenment thinkers used observation and reason to try to solve problems in society. Their work led to new ideas about government, human nature, and human rights.

The Age of Exploration, the Scientific Revolution, and the Enlightenment helped to shape the world we live in today.

The Causes of European Exploration

Why did European exploration begin to flourish in the 1400s? Two main reasons stand out. First, Europeans of this time had several motives for exploring the world. Second, advances in knowledge and technology helped to make the Age of Exploration possible.

Motives for Exploration

For early explorers, one of the main motives for exploration was the desire to find new trade routes to Asia. By the 1400s, merchants and Crusaders had brought many goods to Europe from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Demand for these goods increased the desire for trade.

Europeans were especially interested in spices from Asia. They had learned to use spices to help preserve food during winter and to cover up the taste of food that was no longer fresh.

Trade with the East, however, was difficult and very expensive. Muslims and Italians controlled the flow of goods. Muslim traders carried goods to the east coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Italian merchants then brought the goods into Europe. Problems arose when Muslim rulers sometimes closed the trade routes from Asia to Europe. Also, the goods went through many hands, and each trading party raised the price.

European monarchs and merchants wanted to break the hold that Muslims and Italians had on trade. One way to do so was to find a sea route to Asia. Portuguese sailors looked for a route that went around Africa. Christopher Columbus tried to reach Asia by sailing west across the Atlantic.

Other motives also came into play. Many people were excited by the opportunity for new knowledge. Explorers saw the chance to earn fame and glory, as well as wealth. As new lands were discovered, nations wanted to claim the lands’ riches for themselves.

A final motive for exploration was the desire to spread Christianity beyond Europe. Both Protestant and Catholic nations were eager to make new converts. Missionaries of both faiths followed the paths blazed by explorers.

Advances in Knowledge and Technology

The Age of Exploration began during the Renaissance. The Renaissance was a time of new learning. A number of advances during that time made it easier for explorers to venture into the unknown.

One key advance was in cartography, the art and science of mapmaking. In the early 1400s, an Italian scholar translated an ancient book called Guide to Geography from Greek into Latin. The book was written by the thinker Ptolemy (TOL-eh-mee) in the 2nd century C.E. Printed copies of the book inspired new interest in cartography. European mapmakers used Ptolemy’s work as a basis for drawing more accurate maps.

Discoveries by explorers gave mapmakers new information with which to work. The result was a dramatic change in Europeans’ view of the world. By the 1500s, Europeans made globes, showing Earth as a sphere. In 1507, a German cartographer made the first map that clearly showed North and South America as separate from Asia.

In turn, better maps made navigation easier. The most important Renaissance geographer, Gerardus Mercator (mer-KAY-tur), created maps using improved lines of longitude and latitude. Mercator’s mapmaking technique was a great help to navigators.

An improved ship design also helped explorers. By the 1400s, Portuguese and Spanish shipbuilders were making a new type of ship called a caravel. These ships were small, fast, and easy to maneuver. Their special bottoms made it easier for explorers to travel along coastlines where the water was not deep. Caravels also used lateen sails, a triangular style adapted from Muslim ships. These sails could be positioned to take advantage of the wind no matter which way it blew.

Along with better ships, new navigational tools helped sailors travel more safely on the open seas. By the end of the 1400s, the compass was much improved. Sailors used compasses to find their bearing, or direction of travel. The astrolabe helped sailors determine their distance north or south from the equator.

Finally, improved weapons gave Europeans a huge advantage over the people they met in their explorations. Sailors could fire their cannons at targets near the shore without leaving their ships. On land, the weapons of native peoples often were no match for European guns, armor, and horses.

Portugal Begins the Age of Exploration

The Age of Exploration began in Portugal. This small country is located on the Iberian Peninsula. Its rulers sent explorers first to nearby Africa and then around the world.

Key Portuguese Explorers

The major figure in early Portuguese exploration was Prince Henry, the son of King John I of Portugal. Nicknamed “the Navigator,” Prince Henry was not an explorer himself. Instead, he encouraged exploration and planned and directed many important expeditions.

Beginning in about 1418, Henry sent explorers to sea almost every year. He also started a school of navigation where sailors and mapmakers could learn their trades. His cartographers made new maps based on the information ship captains brought back.

Henry’s early expeditions focused on the west coast of Africa. He wanted to continue the Crusades against the Muslims, find gold, and take part in Asian trade.

Gradually, Portuguese explorers made their way farther and farther south. In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias became the first European to sail around the southern tip of Africa.

In July 1497, Vasco da Gama set sail with four ships to chart a sea route to India. Da Gama’s ships rounded Africa’s southern tip and then sailed up the east coast of the continent. With the help of a sailor who knew the route to India from there, they were able to across the Indian Ocean.

Da Gama arrived in the port of Calicut, India, in May 1498. There he obtained a load of cinnamon and pepper. On the return trip to Portugal, da Gama lost half of his ships. Still, the valuable cargo he brought back paid for the voyage many times over. His trip made the Portuguese even more eager to trade directly with Indian merchants.

In 1500, Pedro Cabral (kah-BRAHL) set sail for India with a fleet of 13 ships. Cabral first sailed southwest to avoid areas where there are no winds to fill sails. But he sailed so far west that he reached the east coast of present-day Brazil. After claiming this land for Portugal, he sailed back to the east and rounded Africa. Arriving in Calicut, he established a trading post and signed trade treaties. He returned to Portugal in June 1501.

The Impact of Portuguese Exploration

Portugal’s explorers changed Europeans’ understanding of the world in several ways. They explored the coasts of Africa and brought back gold and enslaved Africans. They also found a sea route to India. From India, explorers brought back spices, such as cinnamon and pepper, and other goods, such as porcelain, incense, jewels, and silk.

After Cabral’s voyage, the Portuguese took control of the eastern sea routes to Asia. They seized the seaport of Goa (GOH-uh) in India and built forts there. They attacked towns on the east coast of Africa. They also set their sights on the Moluccas, or Spice Islands, in what is now Indonesia. In 1511, they attacked the main port of the islands and killed the Muslim defenders. The captain of this expedition explained what was at stake. If Portugal could take the spice trade away from Muslim traders, he wrote, then Cairo and Makkah “will be ruined.” As for Italian merchants, “Venice will receive no spices unless her merchants go to buy them in Portugal.”

Portugal’s control of the Indian Ocean broke the hold Muslims and Italians had on Asian trade. With the increased competition, prices of Asian goods—such as spices and fabrics—dropped, and more people in Europe could afford to buy them.

During the 1500s, Portugal also began to establish colonies in Brazil. The native people of Brazil suffered greatly as a result. The Portuguese forced them to work on sugar plantations, or large farms. They also tried to get them to give up their religion and convert to Christianity. Missionaries sometimes tried to protect them from abuse, but countless numbers of native peoples died from overwork and from European diseases. Others fled into the interior of Brazil.

The colonization of Brazil also had a negative impact on Africa. As the native population of Brazil decreased, the Portuguese needed more laborers. Starting in the mid–1500s, they turned to Africa. Over the next 300 years, ships brought millions of enslaved West Africans to Brazil.

Later Spanish Exploration and Conquest

After Columbus’s voyages, Spain was eager to claim even more lands in the New World. To explore and conquer “New Spain,” the Spanish turned to adventurers called conquistadors , or conquerors. The conquistadors were allowed to establish settlements and seize the wealth of natives. In return, the Spanish government claimed some of the treasures they found.

Key Explorers

In 1519, Spanish explorer Hernán Cortés (er–NAHN koor–TEZ), with and a band of fellow conquistadors, set out to explore present-day Mexico. Native people in Mexico told Cortés about the Aztecs. The Aztecs had built a large and wealthy empire in Mexico.

With the help of a native woman named Malinche (mah–LIN–chay), Cortés and his men reached the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán (tay–nawh–tee–TLAHN). The Aztec ruler, Moctezuma II, welcomed the Spanish with great honors. Determined to break the power of the Aztecs, Cortés took Moctezuma hostage.

Cortés now controlled the Aztec capital. In 1520, he left the city of Tenochtitlán to battle a rival Spanish force. While he was away, a group of conquistadors attacked the Aztecs in the middle of a religious celebration. In response, the Aztecs rose up against the Spanish. The soldiers had to fight their way out of the city. Many of them were killed during the escape.

The following year, Cortés mounted a siege of the city, aided by thousands of native allies who resented Aztec rule. The Aztecs ran out of food and water, yet they fought desperately. After several months, the Spanish captured the Aztec leader, and Aztec resistance collapsed. The city was in ruins. The mighty Aztec Empire was no more.

Four factors contributed to the defeat of the Aztec Empire. First, Aztec legend had predicted the arrival of a white-skinned god. When Cortés appeared, the Aztecs welcomed him because they thought he might be this god, Quetzalcoatl. Second, Cortés was able to make allies of the Aztecs’ enemies. Third, their horses, armor, and superior weapons gave the Spanish an advantage in battle. Fourth, the Spanish carried diseases that caused deadly epidemics among the Aztecs.

Aztec riches inspired Spanish conquistadors to continue their search for gold. In the 1520s, Francisco Pizarro received permission from Spain to conquer the Inca Empire in South America. The Incas ruled an empire that extended throughout most of the Andes Mountains. By the time Pizarro arrived, however, a civil war had weakened that empire.

In April 1532, the Incan emperor, Atahualpa (ah–tuh–WAHL–puh), greeted the Spanish as guests. Following Cortés’s example, Pizarro launched a surprise attack and kidnapped the emperor. Although the Incas paid a roomful of gold and silver in ransom, the Spanish killed Atahualpa. Without their leader, the Inca Empire quickly fell apart.

The Impact of Later Spanish Exploration and Conquest

The explorations and conquests of the conquistadors transformed Spain. The Spanish rapidly expanded foreign trade and overseas colonization. For a time, wealth from the Americas made Spain one of the world’s richest and most powerful countries.

Besides gold and silver, ships from the Americas brought corn and potatoes to Spain. These crops grew well in Europe. The increased food supply helped spur a population boom. Conquistadors also introduced Europeans to new luxury items, such as chocolate.

In the long run, however, gold and silver from the Americas hurt Spain’s economy. Inflation, or an increase in the supply of money, led to a loss of its value. It now cost people a great deal more to buy goods with the devalued money. Additionally, monarchs and the wealthy spent their riches on luxuries, instead of building Spain’s industries.

The Spanish conquests had a major impact on the New World. The Spanish introduced new animals to the Americas, such as horses, cattle, sheep, and pigs. But they destroyed two advanced civilizations. The Aztecs and Incas lost much of their culture along with their wealth. Many became laborers for the Spanish. Millions died from disease. In Mexico, for example, there were about twenty-five million native people in 1519. By 1605, this number had dwindled to one million.

Other European Explorations

Spain and Portugal dominated the early years of exploration. But rulers in rival nations wanted their own share of trade and new lands in the Americas. Soon England, France, and the Netherlands all sent expeditions to North America.

Key Explorers

Explorers often sailed for any country that would pay for their voyages. The Italian sailor John Cabot made England’s first voyage of discovery. Cabot believed he could reach the Indies by sailing northwest across the Atlantic. In 1497, he landed in what is now Canada. Believing he had reached the northeast coast of Asia, he claimed the region for England.

Another Italian, Giovanni da Verrazano, sailed under the French flag. In 1524, Verrazano explored the Atlantic coast from present-day North Carolina to Canada. His voyage gave France its first claims in the Americas. Unfortunately, on a later trip to the West Indies, he was killed by native people.

Sailing on behalf of the Netherlands, English explorer Henry Hudson journeyed to North America in 1609. Hudson wanted to find a northwest passage through North America to the Pacific Ocean. Such a water route would allow ships to sail from Europe to Asia without entering waters controlled by Spain.

Hudson did not find a northwest passage, but he did explore what is now called the Hudson River in present-day New York State. His explorations were the basis of the Dutch claim to the area. Dutch settlers established the colony of New Amsterdam on Manhattan in 1625.

In 1610, Hudson tried again, this time under the flag of his native England. Searching farther north, he sailed into a large bay in Canada that is now called Hudson Bay. He spent three months looking for an outlet to the Pacific, but there was none.

After a hard winter in the icy bay, some of Hudson’s crew rebelled. They set him, his son, and seven loyal followers adrift in a small boat. Hudson and the other castaways were never seen again. Hudson’s voyage, however, laid the basis for later English claims in Canada.

The Impact of European Exploration of North America

Unlike the conquistadors in the south, northern explorers did not find gold and other treasure. As a result, there was less interest, at first, in starting colonies in that region.

Canada’s shores did offer rich resources of cod and other fish. Within a few years of Cabot’s trip, fishing boats regularly visited the region. Europeans were also interested in trading with Native Americans for whale oil and otter, beaver, and fox furs. By the early 1600s, Europeans had set up a number of trading posts in North America.

English exploration also contributed to a war between England and Spain. As English ships roamed the seas, some captains, nicknamed “sea dogs,” began raiding Spanish ports and ships to take their gold. Between 1577 and 1580, sea dog Francis Drake sailed around the world. He also claimed part of what is now California for England, ignoring Spain’s claims to the area.

The English raids added to other tensions between England and Spain. In 1588, King Philip II of Spain sent an armada, or fleet of ships, to invade England. With 130 heavily armed vessels and about thirty thousand men, the Spanish Armada seemed an unbeatable force. But the smaller English fleet was fast and well armed. Their guns had a longer range, so they could attack from a safe distance. After several battles, a number of the armada’s ships had been sunk or driven ashore. The rest turned around but faced terrible storms on the way home. Fewer than half of the ships made it back to Spain.

The defeat of the Spanish Armada marked the start of a shift in power in Europe. By 1630, Spain no longer dominated the continent. With Spain’s decline, other countries—particularly England and the Netherlands—took a more active role in trade and colonization around the world.

Bartolomé de Las Casas: From Conquistador to Protector of the Indians

Bartolomé de las Casas experienced a remarkable change of heart during his lifetime. At first, he participated in Spain’s conquest and settlement of the Americas. Later in life, he criticized and condemned it. For more than fifty years, he fought for the rights of the defeated and enslaved peoples of Latin America. How did this conquistador become known as “the Protector of the Indians?”

Bartolomé de las Casas (bahr–taw–law–MEY day las KAH-sahs) ran through the streets of Seville, Spain, on March 31, 1493. He was just nine years old and on his way to see Christopher Columbus, who had just returned from his first voyage to the Americas. Bartolomé wanted to see him and the “Indians,” as they were called, as they paraded to the church.

Bartolomé’s father and uncles were looking forward to seeing Columbus, as well. Like many other people in Europe during the late 1400s, they saw the Americas as a place of opportunity. They signed up to join Columbus on his second voyage. Two years after that, Bartolomé followed in his father’s footsteps and voyaged to the Americas himself. He sailed to the island of Hispaniola, the present-day nations of Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Las Casas as Conquistador and Priest

One historian wrote that when Las Casas first arrived in the Americas, he was “not much better than the rest of the gentlemen-adventurers who rushed to the New World, bent on speedily acquiring fortunes.” He supported the Spanish conquest of the Americas and was a loyal servant of Spain’s king and queen, Ferdinand and Isabella. Once in Hispaniola, Las Casas helped to manage his father’s farms and businesses. Enslaved Indians worked in the family’s fields and mines.

Spanish conquistadors wanted to gain wealth and glory in the Americas. They had another goal, as well—to convert Indians to Christianity. Las Casas shared this goal. So, the young conquistador went back to Europe to become a priest. He returned to Hispaniola sometime in 1509 or 1510. There he began to teach and baptize the Indians. At the same time, he continued to manage Indian slaves.

On a Path to Change

History often seems to be made up of moments when someone has a change of heart. The path that he or she has been traveling takes a dramatic turn. It often appears to others that this change is sudden. In reality, a series of events usually causes a person to make the decision to change. One such event happened to Las Casas in 1511.

Roman Catholics in Hispaniola witnessed horrible acts of cruelty and injustice against the native peoples of the West Indies at the hands of the Spanish conquistadors. One of the priests there, Father Antonio de Montesinos, spoke out against the harsh treatment of the Indians in a sermon delivered to a Spanish congregation in Hispaniola in 1511. De Montesinos said:

You are in mortal sin . . . for the cruelty and tyranny you use in dealing with these innocent people . . . by what right or justice do you keep these Indians in such a cruel and horrible servitude? . . . Why do you keep them so oppressed? . . . Are not these people also human beings?

One historian called this sermon “the first cry for justice in America” on behalf of the Indians. Las Casas recorded the sermon in one of his books, History of the Indies . No one is sure if he was present at the sermon or heard about it later. But one thing seems certain; even though he must have seen some of the same injustices described by de Montesinos, Las Casas continued to support the Spanish conquest and the goals of conquering new lands, earning wealth, and converting Indians to Christianity.

However, in 1513, something happened that changed Las Casas’s life. He took part in the conquest of Cuba. As a reward, he received more Indian slaves and an encomienda , or land grant. But he also witnessed a massacre. The Spanish killed thousands of innocent Indians, including women and children, who had welcomed the Spanish into their town. In his book The Devastation of the Indies: A Brief Account , he wrote, “I saw here cruelty on a scale no living being has ever seen or expects to see.”

A Turning Point

The Cuban massacre in 1513 and other scenes of violence against Indians Las Casas witnessed finally pushed him to a turning point. He could no longer believe that the Spanish conquest was right. Before, he had thought that only some individuals acted cruelly and inhumanely. Now he saw that the whole Spanish system of conquest brought only death and suffering to the people of the West Indies.

On August 15, 1514, when he was about thirty years old, Las Casas gave a startling sermon. He asked his congregation to free their enslaved Indians. He also said that they had to return or pay for everything they had taken away from the Indians. He refused to forgive the colonists’ sins in confession if they used Indians as forced labor. Then he announced that he would give up his ownership of Indians and the business he had inherited from his father.

Protector of the Indians

For the rest of his life, Las Casas fought for the rights of the Indians in the Americas. He traveled back and forth to Europe working on their behalf. He talked with popes and kings, debated enemies, and wrote letters and books on the subject.

Las Casas influenced both a pope and a king. In 1537, Pope Paul III wrote that Indians were free human beings, not slaves, and that anyone who enslaved them could be thrown out of the Catholic Church. In 1542, Holy Roman emperor Charles V, who ruled Spain, issued the New Laws, banning slavery in Spanish America.

In 1550 and 1551, Las Casas also took part in a famous debate against Juan Ginés Sepúlveda in Spain. Sepúlveda tried to prove that Indians were “natural slaves.” Many Spanish, especially those hungry for wealth and glory, shared this belief. Las Casas passionately argued against Sepúlveda with the same message he would deliver over and over throughout his life. Las Casas argued that:

• Indians, like all human beings, have rights to life and liberty. • The Spanish stole Indian land through bloody and unjust wars. • There is no such thing as a good encomienda. • Indians have the right to make war against the Spanish.

Las Casas died in 1566. The voices and the deeds of the conquistadors slowly eroded the memory of his words. But in other European countries, people began to read The Devastation of the Indies: A Brief Account . As time passed, more of Las Casas’s works were published. In the centuries to follow, fighters for justice took up his name as a symbol for their own struggles for human rights.

The Legacy of Las Casas

Today, historians remember Las Casas as the first person to actively oppose the oppression of Indians and to call for an end to Indian slavery. Later, in the 19th century, Las Casas inspired both Father Hidalgo, the father of Mexican independence, and Simón Bolívar, the liberator of South America.

In the 1960s, Mexican American César Chávez learned about injustice at an early age. His family worked as migrants, moving from place to place to pick crops. With barely an eighth-grade education, Chávez organized workers, formed a union, and won better pay and better working and living conditions. Speaking for the powerless, he rallied people to his side with his cry, “Sí, Se Puede!” (“Yes, We Can!”) Just as the name “Chávez” will always be connected to the struggles of the farm workers, the name “Las Casas” will forever be connected to any fight for human rights and dignity for the native people of the Americas.

The Impact of Exploration on Europe

The voyages of explorers had a dramatic impact on European commerce and economies. As a result of exploration, more goods, raw materials, and precious metals entered Europe. Mapmakers carefully charted trade routes and the locations of newly discovered lands. By the 1700s, European ships traveled trade routes that spanned the globe. New centers of commerce developed in the port cities of the Netherlands and England.

Exploration and trade contributed to the growth of capitalism. This economic system is based on investing money for profit. Merchants gained great wealth by trading and selling goods from around the world. Many of them used their profits to finance still more voyages and to start trading companies. Other people began investing money in these companies and shared in the profits. Soon, this type of shared ownership was applied to other kinds of businesses.

Another aspect of the capitalist economy concerned the way people exchanged goods and services. Money became more important as precious metals flowed into Europe. Instead of having a fixed price, items were sold for prices that were set by the open market. This meant that the price of an item depended on how much of the item was available and how many people wanted to buy it. Sellers could charge high prices for scarce items that many people wanted. If the supply of an item was large and few people wanted it, sellers lowered the price. This kind of system, based on supply and demand, is called a market economy.

Labor, too, was given a money value. Increasingly, people began working for hire instead of directly providing for their own needs. Merchants hired people to work from their own cottages, turning raw materials from overseas into finished products. This growing cottage industry was especially important in the manufacture of textiles. Often, entire families worked at home, spinning wool into thread or weaving thread into cloth. Cottage industry was a step toward the system of factories operated by capitalists in later centuries.

A final result of exploration was a new economic policy called mercantilism. European rulers believed that building up wealth was the best way to increase a nation’s power. For this reason, they tried to reduce the products they bought from other countries and to increase the items they sold.

Having colonies was a key part of this policy. Nations looked to their colonies to supply raw materials for their industries at home. These industries turned the raw materials into finished goods that they could sell back to their colonies, as well as to other countries. To protect this valuable trade with their colonies, rulers often forbade colonists from trading with other nations.

Originally published by Flores World History , free and open access, republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Chapter 1 — Worlds Collide: Before and After 1492

The origins of european exploration, learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the major historical developments that fueled Europe’s “age of exploration”

- Explain the significance of Portugal’s expansion into Africa and the neighboring Atlantic islands, particularly for the slave trade out of Africa

- Discuss the motives for early Portuguese and Spanish exploration, including Columbus’s voyage to the New world

Long before the famed mariner Christopher Columbus “discovered” America for the Europeans, Norse (Viking) seafarers from Scandinavia established colonial outposts in Iceland and Greenland and, around the year 1000, Leif Erikson reached Newfoundland in present-day Canada. But the colonies failed. Culturally and geographically isolated, a combination of limited resources, inhospitable weather, food shortages, and Native resistance drove the Norse back into the sea. It was explorers sailing for Portugal and Spain who ushered in an unprecedented age of exploration and contact with the Americas beginning in the fifteenth century.

In the hundreds of years that passed between these two episodes of Atlantic exploration, Europe had experienced tremendous change. Greater contact with the East had helped inspire a Renaissance in scholarship and art while introducing new trade goods. In the 1340s, merchants returning from the region of the Black Sea unwittingly brought with them the bubonic plague. Within a few short years about one-third of Europe’s population had perished. A high birth rate, however, coupled with bountiful harvests, brought dramatic population growth during the next century. Meanwhile, European nation-states began to consolidate their power under the authority of ambitious kings and queens. By 1492, when Christopher Columbus’s three ships landed in the Bahamas, Europe had emerged from the long Middle Ages and was poised to seize a permanent place in the history of the Americas.

EUROPE ON THE BRINK OF CHANGE

The story of Columbus’s arrival in the Americas might be said to have begun as far back as the Crusades. A series of military conflicts waged between Christians and Muslims after Muslim rulers had gained control over the Holy Land, the Crusades brought Europeans into closer contact with the Middle East. Religious zeal inspired many of the knights who volunteered to fight on behalf of Christendom. Adventure, the chance to win land and titles, and the Church’s promise of wholesale forgiveness of sins also motivated many. The battle for the Holy Lands did not conclude until the Crusaders lost their Mediterranean stronghold at Acre (in present-day Israel) in 1291 and the last of the Christians left the area a few years later.

This map of the early Crusades, from the collection of the Norman B. Levanthal Map Center, shows the extent of the contested region in the east and the routes of the crusading armies from Europe.

Although the Crusaders did not ultimately succeed in their goals, the experience of the Crusades had profound effects, both positive and negative. On the negative side, the wide-scale persecution of Jews began. Christians classed them with the infidel Muslims and labeled them “the killers of Christ.” In the coming centuries, kings either expelled Jews from their kingdoms or forced them to pay heavy tributes for the privilege of remaining. Muslim-Christian hatred also festered, and intolerance grew.

On the positive side, maritime trade between East and West expanded. As Crusaders experienced the feel of silk, the taste of spices, and the utility of porcelain, desire for these products created new markets for merchants. In particular, the Adriatic port city of Venice prospered enormously from trade with Islamic merchants. From the days of the early adventurer Marco Polo, Venetian sailors had traveled to ports on the Black Sea and established their own colonies along the Mediterranean Coast. From there, they gained overland access to goods from the East, traded hundreds of miles along routes collectively known as the Silk Road. But transporting goods along the old Silk Road was costly, slow, and unprofitable. Muslim middlemen collected taxes as the goods changed hands. Robbers waited to ambush the treasure-laden caravans. A direct water route to the East, cutting out the land portion of the trip, would allow European merchants to maximize returns. In addition to seeking a water passage to the wealthy cities in the East, sailors wanted to find a route to the exotic and wealthy Spice Islands in modern-day Indonesia and the East Indies, whose location was kept secret by Muslim rulers. Longtime rivals of Venice, the merchants of Genoa and Florence also looked to expand their commercial interests.

PORTUGUESE EXPLORATION

Located on the Iberian Peninsula of southwestern Europe, Portugal, with its port city of Lisbon, soon became the center for merchants desiring to undercut the Venetians’ hold on trade. With a population of about one million and supported by its ruler Prince Henry, whom historians call “the Navigator,” this independent kingdom fostered exploration of and trade with western Africa. Skilled shipbuilders and navigators who took advantage of maps from all over Europe, Portuguese sailors used triangular sails and built lighter vessels called caravels that could sail down the African coast on longer ocean voyages. Portuguese mariners also began to use the astrolabe, a tool to calculate latitude, that allowed for more precise navigation on the open seas.

Motivated by economic as well as religious goals, the Portuguese established forts along the Atlantic coast of Africa during the fifteenth century. Their trading posts there generated new profits that funded further trade and further colonization. By the end of the fifteenth century the Portuguese mariner Vasco de Gama leapfrogged his way southward and around the southern tip of Africa to reach the Indian Ocean. From there he followed the winds to India and lucrative Asian markets. Meanwhile, the vagaries of ocean currents and the limits of the day’s technology forced other Portuguese, as well as Spanish, mariners to sail west into the open sea before cutting back east to Africa. So doing, the Portuguese and Spanish stumbled upon several islands off the Atlantic coast of Europe and Africa, including the Azores, the Canary Islands, and the Cape Verde Islands. Although small and little known to Americans today, these islands became training grounds for the later colonization of the New World, particularly the cultivation of sugar.