1998 Tour de France

85th edition: july 11 - august 28, 1998, results, stages with running gc, map, photos and history.

1997 Tour | 1999 Tour | Tour de France database | 1998 Tour Quick Facts | Final GC | Individual stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1998 Tour de France

Quick Facts about the 1998 Tour de France :

The Golden Saying of Epictetus are available as an audiobook here. For the Kindle eBook version, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

3,875 kilometers ridden at an average speed of 39.983 km/hr

The race started in Ireland, where the prologue and first two stages were held. Then the race transferred to Brittany for a counter-clockwise trip around France, finishing in Paris.

189 riders started, 96 finished.

The 1998 Tour was marred by the Festina doping scandal that turned into the greatest crisis in the Tour's history.

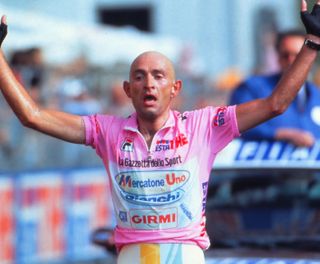

1997 winner Jan Ullrich arrived in poor form, allowing 1998 Giro winner Marco Pantani to take huge amounts of time in the mountains, in particular, stage 15 to Les Deux Alpes.

Marco Pantani is the last man to do the Giro-Tour double.

- Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno): 92hr 49min 46sec

- Jan Ullrich (Telekom) @ 3min 21sec

- Bobby Julich (Cofidis) @ 4min 8sec

- Christophe Rinero (Cofidis) @ 9min 16sec

- Michael Boogerd (Rabobank) @ 11min 26sec

- Jean-Cyril Robin (US Postal) @ 14min 47sec

- Roland Meier (Mapei-Bricobi) @ 15min 13sec

- Daniele Nardello (Mapei Bricobi) @ 16min 7sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande (Polti) @ 17min 35sec

- Axel Merckx (Polti) @ 17min 39sec

- Bjarne Riis (Telekom) @ 19min 10sec

- Dariusz Baranowski (US Postal) @ 19min 58sec

- Stéphane Heulot (FDJ) @ 20min 57sec

- Leonardo Piepoli (Saeco) @ 22min 45sec

- Bo Hamburger (Casino) @ 26min 39sec

- Kurt Van Wouwer (Lotto) @ 27min 20sec

- Kevin Livingston (Cofidis) @ 34min 3sec

- Jörg Jaksche (Polti) @ 35min 41sec

- Peter Farazijn (Lotto) @ 36min 10sec

- Andreï Teteriouk (Lotto) @ 37min 3sec

- Udo Bolts (Telekom) @ 37min 25sec

- Laurent Madouas (Lotto) @ 39min 54sec

- Geert Verheyen (Lotto) @ 41min 23sec

- Cedric Vasseur (Gan) @ 42min 14sec

- Evgeni Berzin (FDJ) @ 42min 51sec

- Thierry Bourguignon (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 43min 53sec

- Georg Totschnig (Telekom) @ 50min 13sec

- Benoit Salmon (Casino) @ 51min 18sec

- Alberto Elli (Casino) @ 1hr 13sec

- Philippe Bordenave (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 1hr 5min 55sec

- Christophe Agnolutto (Casino) @ 1hr 11min 3sec

- Oscar Pozzi (Asics) @ 1hr 14min 54sec

- Maarten Den Bakker (Rabobank) @ 1hr 16min 21sec

- Patrick Joncker (Rabobank) @ 1hr 16min 49sec

- Pascal Chanteur (Casino) @ 1hr 19min 32sec

- Massimiliano Lelli (Cofidis) @ 1hr 20min 32sec

- Massimo Podenzana (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 20min 47sec

- Viatcheslav Ekimov (US Postal) @ 1hr 22min 40sec

- Denis Leproux (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 1hr 25min 5sec

- Beat Zberg (Rabobank) @ 1hr 26min 8sec

- Lylian Lebreton (Big Mat-Auber) @ 1hr 28min 19sec

- Andrea Tafi (Mapei) @ 1hr 29min 22sec

- Rolf Aldag (Telekom) @ 1hr 29min 27sec

- Koos Moerenhout (Rabobank) @ 1hr 29min 37sec

- Peter Meinert (US Postal) @ 1hr 29min 52sec

- Riccardo Forconi (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 30min 33sec

- Fabio Sacchi (Polti) @ 1hr 31min 53sec

- Marty Jemison (US Postal) @ 1hr 34min 27sec

- Nicolas Jalabert (Cofidis) @ 1hr 38min 45sec

- Massimo Donati (Saeco) @ 1hr 38min 59sec

- Tyler Hamilton (US Postal) @ 1hr 39min 53sec

- Simone Borgheresi (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 40min 4sec

- George Hincapie (US Postal) @ 1hr 40min 39sec

- Stuart O'Grady (Gan) @ 1hr 46min 4sec

- Filippo Simeoni (Asics) @ 1hr 47min 19sec

- Jens Heppner (Telekom) @ 1hr 50min 43sec

- François Simon (Gan) @ 1hr 52min 41sec

- Frankie Andreu (US postal) @ 1hr 53min 44sec

- Thierry Gouvenou (Big Mat-Auber 93)) @ 1hr 55min 20sec

- Roberto Conti (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 55min 33sec

- Laurent Desbiens (Cofidis) @ 1hr 56min 28sec

- Erik Zabel (Telekom) @ 1hr 56min 57sec

- Leon Van Bon (Rabobank) @ 1hr 57min 30sec

- Paul Van Hyfte (Lotto) @ 1hr 58min 2sec

- Jacky Durand (Casino) @ 1hr 59min 42sec

- Christophe Mengin (FDJ) @ 2hr 0min 35sec

- Frédérick Guesdon (FDJ) @ 2hr 5min 8sec

- Wilfried Peeters (Mapei) @ 2hr 6min 16sec

- Rik Verbrugghe (Lotto) @ 2hr 6min 17sec

- Magnus Bäckstedt (Gan) @ 2hr 8min 30sec

- Eddy Mazzoleni (Saeco) @ 2hr 10min 19sec

- Fabio Fontanelli (Mercatone Uno) @ 2hr 11min 37sec

- Stefano Zanini (Mapei) @ 2hr 12min 11sec

- Alain Turicchia (Asics) @ 2hr 14min 12sec

- Mirko Crepaldi (Polti) @ 2hr 15min 5sec

- Diego Ferrari (Asics) @ 2hr 15min 46sec

- Xavier Jan (FDJ) @ 2hr 15min 51sec

- Pacal Lino (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 2hr 16min 13sec

- Fabio Roscioli (Asics) @ 2hr 17min 53sec

- Christian Henn (Telekom) @ 2hr 19min 52sec

- Vjatjeslav Djavanian (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 2hr 21min 31sec

- Rossano Brasi (Polti) @ 2hr 22min 10sec

- Jens Voigt (Gan) @ 2hr 25min 14sec

- Pascal Deramé (US Postal) @ 2hr 26min 25sec

- Tom Steels (Mapei) @ 2hr 26min 30sec

- Eros Poli (Gan) @ 2hr 31min 56sec

- Alecei Sivakov (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 2hr 33min 19sec

- Aart Vierhouten (Rabobank) @ 2hr 35min 6sec

- Robbie McEwen (Rabobank) @ 2hr 36min 32sec

- Paolo Fornaciari (Saeco) @ 2hr 37min 50sec

- Massimiliano Mori (Saeco) @ 2hr 38min 12sec

- Bart Leysen (Mapei) @ 2hr 39min 43sec

- Francesco Frattini (Telekom) @ 2hr 43min 16sec

- Franck Bouyer (FDJ) @ 2hr 43min 45sec

- Mario Traversoni (Mercatone Uno) @ 2hr 44min 2sec

- Damien Nazon (FDJ) @ 3hr 12min 15sec

- Erik Zabel (Telekom): 327 points

- Stuart O'Grady (Gan): 230

- Tom Steels (Mapei-Bricobi): 221

- Robbie McEwen (Rabobank): 196

- George Hincapie (US postal): 151

- François Simon (Gan): 149

- Bobby Julich (Cofidis): 114

- Jacky Durand (Casino): 111

- Alain Turicchia (Asics): 99

- Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno): 90

- Christophe Rinero (Cofidis): 200 points

- Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno): 175

- Alberto Elli (Casino): 165

- Cédric Vasseur (Gan): 156

- Stéphane Heulot (FDJ): 152

- Jan Ullrich (Telekom): 126

- Bobby Julich (Cofidis): 98

- Michael Boogerd (Rabobank): 92

- Leonardo Piepoli (Saeco): 90

- Roland Meier (Cofidis): 89

Team Classification:

- Cofidis: 278hr 29min 58sec

- Casino @ 29min 9sec

- US Postal @ 41min 40sec

- Telekom @ 46min 1sec

- Lotto @ 1hr 4min 14sec

- Polti @ 1hr 6min 32sec

- Rabobank @ 1hr 46min 20sec

- Mapei @ 1hr 59min 53sec

- Big Mat-Auber 93 @ 2hr 3min 32sec

- Mercatone Uno @ 2hr 23min 4sec

- Jan Ullrich (Telekom) 92hr 53min 7sec

- Christophe Rinero (Cofidis) @ 5min 55sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande (Mapei) @ 14min 14sec

- Kevin Levingston (Cofidis) @ 30min 42sec

- Jörg Jaksche (Polti) @ 32min 20sec

Content continues below the ads

Individual stage results with running GC:

Prologue: Saturday, July 11, Dublin, Ireland 5.6 km Individual Time Trial

- Chris Boardman: 6min 12sec

- Abraham Olano @ 4sec

- Laurent Jalabert @ 5sec

- Bobby Julich s.t.

- Christophe Moreau s.t.

- Jan Ullrich s.t.

- Alex Zulle @ 7sec

- Laurent Dufaux @ 9sec

- Andrei Tchmil @ 10sec

- Viatcheslav Ekimov @ 11sec

GC: Same as Prologue time, there was no time bonus in play in the prologue.

Stage 1: Sunday, July 12, Dublin, Ireland - Dublin, Ireland, 180.5 km.

- Tom Steels: 4hr 29min 58sec

- Erik Zabel s.t.

- Robbie McEwen s.t.

- Gian-Matteo Fagnini s.t.

- Nicola Minali s.t.

- Frederic Moncassin s.t.

- Philippe Gaumont s.t.

- Mario Traversoni s.t.

- François Simon s.t.

- Jan Svorada s.t.

GC after Stage 1:

- Chris Boardman

- Erik Zabel @ 7sec

- Tom Steels @ 9sec

- Laurent Dufaux s.t.

Stage 2: Monday, July 13, Enniscorthy, Ireland - Cork, Ireland, 205.5 km.

- Jan Svorada: 5hr 45min 10sec

- Mario Cipollini s.t.

- Alain Turicchia s.t.

- Tom Steels s.t.

- Emmanuel Magnien s.t.

- Jan Kirsipuu s.t.

- Jeroen Blijlevens s.t.

- Silvio Martinello s.t.

GC after Stage 2:

- Tom Steels @ 7sec

- Abraham Olano @ 8sec

- Laurent Jalabert @ 9sec

- Jan Svorada @ 10sec

- Robbie McEwen @ 11sec

Stage 3: Tuesday, July 14, The Tour returns to France. Roscoff - Lorient, 169 km.

- Jens Heppner: 3hr 33min 36sec

- Xavier Jan s.t.

- George Hincapie @ 2sec

- Bo Hamburger s.t.

- Stuart O'Grady s.t.

- Vicente Garcia-Acosta s.t.

- Pascal Hervé s.t.

- Francisco Cabello s.t.

- Pascal Chanteur @ 5sec

- Fabrizio Guidi @ 1min 10sec

GC after Stage 3:

- Bo Hamburger

- Stuart O'Grady @ 3sec

- Jens Heppner s.t.

- Xavier Jan @ 21sec

- Pascal Hervé @ 22sec

- Vicente Garcia-Acosta @ 23sec

- Pascal Chanteur @ 28sec

- Francisco Cabello @ 47sec

- Erik Zabel @ 1min 2sec

Stage 4: Wednesday, July 15, Plouay - Cholet, 252 km.

- Jeroen Blijlevens: 5hr 48min 32sec

- Andrei Tchmil s.t.

- Lars Michaelsen s.t.

- Maximilian Sciandri s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

GC after stage 4:

- Stuart O'Grady

- Bo Hampburger @ 11sec

- George Hincapie s.t.

- Jens Heppner @ 14sec

- Xavier Jan @ 32sec

- Pascal Hervé @ 33sec

- Vicente Garcia-Acosta @ 34sec

- Pascal Chanteur @ 39sec

- Francisco Cabello @ 58sec

- Erik Zabel @ 1min 1sec

Stage 5: Thursday, July 16, Cholet - Châteauroux, 228.5 km.

- Mario Cipollini: 5hr 18min 49sec

- Christophe Mengin s.t.

- Andrea Farrigato s.t.

- Fabrizio Guidi s.t.

- Alessio Bongioni s.t.

GC after Stage 5:

- George Hincapie @ 7sec

- Bo Hamburger @ 11sec

- Pacal Hervé @ 33sec

- Erik Zabel @ 45sec

Stage 6: Friday, July 17, Le Châtre - Brive la Gaillarde, 204.5 km.

- Mario Cipollini: 5hr 5min 32sec

- Emmanuele Magnien s.t.

GC after Stage 6:

- George Hincapie @ 9sec

- Bo Hamburger @ 13sec

- Jens Heppner @ 16sec

- Xavier Jan @ 34sec

- Pascal Hervé @ 35sec

- Vicente Garcia-Acosta @ 36sec

- Pascal Chanteur @ 41sec

- Erik Zabel @ 43sec

- Jan Svorada @ 47sec

Stage 7: Saturday, July 18, Meyrignac l'Église- Corrèze 58 km Individual Time Trial.

The Festina team was forced to withdraw from the Tour before the start of the time trial.

- Jan Ullrich: 1hr 15min 25sec

- Tyler Hamilton @ 1min 10sec

- Bobby Julich @ 1min 18sec

- Laurent Jalabert @ 1min 24sec

- Viatcheslav Ekimov @ 1min 40sec

- Abraham Olano @ 2min 13sec

- Evgeni Berzin @ 2min 21sec

- Francesco Casagrande @ 2min 22sec

- Stephane Heulot @ 2min 22sec

- Bo Hamburger @ 2min 29sec

GC after Stage 7:

- Jan Ullrich: 31hr 24min 37sec

- Bo Hamburger @ 1min 18sec

- Laurent Jalabert @ 1min 14sec

- Tyler Hamilton @ 1min 30sec

- Viatcheslav Ekimov @ 1min 46sec

- Vicente Garcia-Acosta @ 1min 50sec

- Stuart O'Grady @ 1min 53sec

- Abraham Olano @ 2min 12sec

- Jens Heppner @ 2min 17sec

Stage 8: Sunday, July 19, Brive la Gaillarde - Montauban, 190.5 km.

- Jacky Durand: 4hr 40min 55sec

- Andrea Tafi s.t.

- Fabio Sacchi s.t.

- Eddy Mazzoleni s.t.

- Laurent Desbiens s.t.

- Joona Laukka s.t.

- Philippe Gaumont @ 1min 34sec

- Erik Zabel @ 7min 45sec

- Serguei Ivanov s.t.

GC after Stage 8:

- Laurent Desbiens

- Andrea Tafi @ 14sec

- Jacky Durand @ 43sec

- Joona Laukka @ 2min 54sec

- Jan Ullrich @ 3min 21sec

- Bo Hamburger @ 4min 39sec

- Laurent Jalabert @ 4min 45sec

- Tyler Hamilton @ 4min 51sec

- Viatcheslav Ekimov @ 5min 7sec

Stage 9: Monday, July 20, Montauban - Pau, 210 km.

- Leon Van Bon: 5hr 21min 10sec

- Jens Voigt s.t.

- Masimilliano Lelli s.t.

- Christophe Agnolutto s.t.

- Erik Zabel @ 12sec

GC after stage 9:

- Laurent Desbiens: 41hr 31min 18sec

- Vicente Garcia-Acosta @ 5min 11sec

Stage 10: Tuesday, July 21, Pau - Luchon, 196.5 km.

- Rudolfo Massi: 5hr 49min 40sec

- Marco Pantani @ 36sec

- Michael Boogerd @ 59sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande s.t.

- Jose-Maria Jimenez s.t.

- Fernando Escartin s.t.

- Jean-Cyril Robin s.t.

- Leonardo Piepoli s.t.

GC after Stage 10:

- Jan Ullrich: 47hr 25min 18sec

- Bo Hamburger @ 2min 17sec

- Laurent Jalabert @ 2min 38sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 3min 3sec

- Abraham Olano @ 3min 11sec

- Michael Boogerd @ 3min 36sec

- Evgeni Berzin @ 3min 39sec

- Stephane Heulot @ 3min 40sec

- Bjarne Riis @ 3min 51sec

- Marco Pantani @ 4min 41sec

Stage 11: Wednesday, July 22, Luchon - Plateau de Beille, 170 km.

- Marco Pantani: 5hr 15min 27sec

- Roland Meier @ 1min 26sec

- Bobby Julich @ 1min 33sec

- Michael Boogerd s.t.

- Christophe Rinero s.t.

- Jan Ullrich @ 1min 40sec

- Kevin Livingston @ 2min 1sec

- Angel Casero @ 2min 3sec

GC after Stage 11:

- Jan Ullrich: 52hr 42min 25sec

- Bobby Julich @ 1min 11sec

- Laurent Jalabert @ 3min 1sec

- Marco Pantani s.t.

- Michael Boogerd @ 3min 29sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 4min 16sec

- Bo Hamburger @ 4min 44sec

- Fernando Escartin @ 5min 16sec

- Roland Meier @ 5min 18sec

- Angel Casero @ 5min 53sec

Stage 12: Friday, July 24, Tarascon sur Ariège - Le Cap d'Agde, 222 km.

- Tom Steels: 4hr 12min 51sec

- Stephane Barthe s.t.

- Andrea Ferrigato s.t.

- Aert Vierhouten s.t.

- Leonardo Guidi s.t.

GC after Stage 12:

- Jan Ullrich: 56hr 55min 16sec

Stage 13: Saturday, July 25, Frontignan la Peyrade - Carpentras, 196 km.

- Daniele Nardello: 4hr 32min 46sec

- Stephane Heulot s.t.

- Marty Jamison s.t.

- Koos Moerenhout s.t.

- Serguei Ivanov @ 2min 27sec

- Fabio Roscioli @ 2min 43sec

- François Simon

- Maarten Den Bakker s.t.

GC after Stage 13:

- Jan Ullrich: 61hr 30min 53sec

- Stephane Heulot @ 5min 5sec

Stage 14: Sunday, July 26, Valréas - Grenoble, 186.5 km.

- Stuart O'Grady: 4hr 30min 53sec

- Orlando Rodriguez s.t.

- Leon Van Bon s.t.

- Peter Meinert s.t.

- Giuseppe Calcaterra s.t. (Crossed the line 2nd, but relegated for not holding his line in the sprint.

- Frederic Guesdon @ 8min 27sec

- Rafael Diaz Justo s.t.

- Erik Zabel @ 10min 5sec

GC after Stage 14:

- Jan Ullrich: 66hr 11min 51sec

Stage 15: Monday, July 27, Grenoble - Les Deux Alpes, 189 km.

- Marco Pantani: 5hr 43min 45sec

- Rudolfo Massi @ 1min 54sec

- Fernando Escartin @ 1min 59sec

- Christophe Rinero @ 2min 57sec

- Bobby Julich @ 5min 43sec

- Michael Boogerd @ 5min 48sec

- Marcos Serrano @ 6min 4sec

- Jean-Cyril Robin @ 6min 34sec

- Manuel Beltran @ 6min 40sec

- Dariusz Baranowski s.t.

25. Jan Ullrich @ 8min 57sec

GC after Stage 15:

- Marco Pantani: 71hr 58min 37sec

- Bobby Julich @ 3min 53sec

- Fernando Escartin @ 4min 14sec

- Jan Ullrich @ 5min 56sec

- Christophe Rinero @ 6min 12sec

- Michael Boogerd @ 6min 16sec

- Rodolfo Massi @ 7min 53sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 8min 1sec

- Roland Meier @ 8min 57sec

- Daniele Nardello @ 9min 14sec

Stage 16: Tuesday, July 28, Vizille - Albertville, 204 km.

- Jan Ullrich: 5hr 39min 47sec

- Bobby Julich @ 1min 49sec

- Axel Merckx s.t.

- Bjarne Riis s.t.

GC after Stage 16:

- Marco Pantani: 77hr 38min 24sec

- Bobby Julich @ 5min 42sec

- Fernando Escartin @ 6min 3sec

- Christophe Rinero @ 8min 1sec

- Michael Boogerd @ 8min 5sec

- Rodolfo Massi @ 12min 15sec

- Jean-Cyril Robin @ 12min 34sec

- Leonardo Piepoli @ 12min 45sec

- Roland Meier @ 13min 19sec

Stage 17: Wednesday, July 29, Aix-les Bains - Vasseur, 149 km.

After a riders' strike in which they completed the course slowly, without their backnumbers, the stage was annulled. Teams ONCE, Riso Scotti and Banesto abandoned the race.

Stage 18: Thursday, July 30, Aix les Bains - Neuchatel (Switzerland), 218.5 km.

- Tom Steels: 4hr 53min 27sec

- Jacky Durand s.t.

- Nicolas Jalabert s.t.

- Aert Vierhouoten s.t.

- Viatcheslav Djavanian s.t.

GC after Stage 18:

- Marco Pantani: 82hr 31min 51sec

- Daniele Nardello @ 13min 36sec

- Bjarne Riis @ 14min 45sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 15min 13sec

Stage 19: Friday, July 31, La Chaux de Fonds (Switzerland) - Autun, 242 km.

Team TVM abandoned.

- Magnus Backstedt: 5hr 10min 14sec

- Maarten De Bakker s.t.

- Pascal Derame s.t.

- Frederic Guesdon @ 25sec

- Thierry Gouvenou s.t.

GC after Stage 19:

- Marco Pantani: 87hr 58min 43sec

Stage 20: Saturday, August 1, Montceau les Mines - Le Creusot 52 km individual time trial.

- Jan Ullrich: 1hr 3min 52sec

- Bobby Julich @ 1min 1sec

- Marco Pantani @ 2min 35sec

- Dariusz Baranowski @ 3min 11sec

- Andrei Teteriouk @ 3min 46sec

- Viatcheslav Ekimov @ 3min 48sec

- Christophe Rinero @ 3min 50sec

- Riccardo Forconi @ 3min 55sec

- Axel Merckx @ 3min 59sec

- Roland Meier @ 4min 29sec

GC after Stage 20:

- Marco Pantani: 89hr 5min 10sec

- Bobby Julich @ 4min 8sec

- Christophe Rinero @ 9min 16sec

- Michael Boogerd @ 11min 26sec

- Jean-Cyril Robin @ 14min 57sec

- Roland Meier @ 15min 13sec

- Danielo Nardello @ 16min 7sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 15min 35sec

- Axel Merckx @ 17min 39sec

21st and Final Stage: Sunday, August 2, Melun - Paris (Champs Elysées), 147.5 km.

- Tom Steels: 3hr 44min 36sec

- Stefano Zanini s.t.

- Mario Taversoni s.t.

- Damien Nazon s.t.

Complete Final 1998 Tour de France General Classification.

The Story of the 1998 Tour de France:

These excerpts are from "The Story of the Tour de France", Volume 2. If you enjoy them we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print, eBook or audiobook. The Amazon link here will make the purchase easy.

Always looking to make the Tour interesting as well as profitable for its owners, the 1998 edition started in Dublin, Ireland. The prologue and the first 2 stages were to be held on the Emerald Isle. Then, without a rest day, the riders were to be transferred to Roscoff on the northern coast of Brittany. Then the Tour headed inland for a couple of stages before turning directly south for the Pyrenees, then the Alps and then Paris. This wasn't a race loaded with hilltop finishes but it did have 115.6 kilometers of individual time trial including 52 in the penultimate stage. This should have been a piece of cake for Ullrich. He not only won the Tour de France in 1997, he won the HEW Cyclassics and the Championship of Zurich.

Ullrich was a well-rounded rider who could do anything and who truly deserved his Number 2 world ranking. But the demands of his fame were more than he could handle. His autobiography Ganz oder Ganz Nicht (All or Nothing at All) is disarmingly frank and honest about his troubles. After the 1997 Tour he signed contracts for endorsements that gave him staggering sums of money. He would never have to worry about a paycheck again. Over the winter his weight had ballooned and his form was suspect. In his words, he had begun 1998 with a new personal best, he weighed more than he had ever weighed in his entire life. In the post-Tour celebrations, he let himself go. He said that after winning the Tour, training was the furthest thing from his mind. He then fell into a vicious cycle. He couldn't find good form and good health. He would lie in bed frustrated, and shovel down chocolate. He would then go out and train too hard for his lapsed form and then get sick again.

He rationalized things. "I can't just train all year long. My life consists of more than cycling," he told himself. Meanwhile, his trainer Peter Becker ground his teeth in frustration seeing his prodigiously talented client riding fewer than 50 kilometers a day.

The results of his winter excess were obvious. He attained no notable successes in the spring, but in the new era of Tour specialization this wasn't necessarily a sign that things were going wrong. Yet in Ullrich's case there were few signs that things were going right. In March he pulled out of the Tirreno–Adriatico only 30 kilometers into the first stage.

Ullrich had a new foe in the 1998 Tour. Marco Pantani had been a Charly Gaul-type racer who would detonate on a climb and bring himself to a high placing in a single stage. In May he proved that he could do more than just climb when he won the Giro d'Italia. The signal that Pantani was riding on a new level was the penultimate stage, a 34-kilometer time trial. He lost only 30 seconds to one of the masters of the discipline, Sergey Gonchar. As we noted in 1997, Pantani had suffered a horrific racing accident in 1995 that shattered his femur. He became determined to return to his former high level and through assiduous training he exceeded his former level. There was a telling flag that wasn't made known until later. Technologists checking Pantani's blood after the accident in Turin found that his hematocrit was over 60 percent.

Hematocrit is the measurement of the percentage of blood volume that is occupied by red blood cells, the tools the body uses to feed oxygen to the muscles. Normal men of European descent have a hematocrit in the low to mid 40s. It declines slightly as a response to the effects of training. It would not be expected to increase during a stage race, as some racers have asserted. Exceptional people may exceed that by a significant amount. Damiano Cunego, winner of the 2004 Giro, through a fortunate twist of genetic fate has a natural hematocrit of about 53. To improve sports performances endurance athletes took to using synthetic EPO or erythropoietin, a drug that raises the user's hematocrit. This is not without danger because as the hematocrit rises, so does the blood's viscosity. By the late 1990s athletes were dying in their sleep as their lower sleeping heart rates couldn't shove the red sludge through their blood vessels. Until 2004 there was no way to test for EPO so the only thing limiting how much EPO an athlete would use was his willingness to tempt death. A friend of mine traveled with a famous Spanish professional racing team in the 1990s and was horrified to see the riders sleeping with heart monitors hooked up to alarms. If the athlete's sleeping heart rate should fall below a certain number, he was awakened, given a saline injection, and put on a trainer. In January of 1997 the UCI implemented the 50% rule. If a rider were found to have a hematocrit exceeding 50% he would be suspended for 2 weeks. Since there was no test at the time to determine if a rider had synthetic EPO in his system, the 2-week suspension wasn't considered a positive for dope, only a suspension so that the rider could "regain his health". There were ways for cagey riders to get around the 50% limit, but that story is for 1999.

So let's get one thing straight and understood. Doping was and is part of the sport. As we proceed through the sordid story of 1998, the actions of the riders to protect themselves and their doping speak for themselves. Without a positive test no single rider may be accused but as a group they are guilty. As individuals, unless proven otherwise, the riders are all innocent. As Miguel Indurain asked after he was accused of doping long after he had retired, "How do I prove my innocence?" He's right. It's almost impossible to prove a negative, that is, that a rider didn't do something.

Yet, complicating matters is that a rational, knowledgeable person knows that just because a rider has never tested positive for dope doesn't mean that he has been riding clean. Many riders who never failed a drug test have later been found to be cheaters, as in the case of World Time Trial Champion David Millar. But again, we must be fair. In the absence of a positive test in which the chain of custody of the samples is guaranteed and a fair appeals process is in place to protect the rider's interests, I grit my teeth and consider a rider innocent.

The prologue for the 1998 Tour was on July 11 but the story of the Tour starts in March when a car belonging to the Dutch team TVM was found to have a large cache of drugs. Fast forward to July 8. Team Festina soigneur Willy Voet was searched at a customs stop as he was on his way from Belgium to Calais and then on to the Tour's start in Dublin. What the customs people found in his car set the cycling world on fire. Among the items Voet was transporting were 234 doses of EPO, testosterone, amphetamines and other drugs that could only have one purpose, to improve the performance of the riders on the Festina team. For now we'll leave Voet in the hands of the police who took him to Lille for further searching and questioning.

In Dublin Chris Boardman won the 5.6-kilometer prologue with a scorching speed of 54.2 kilometers an hour. Ullrich momentarily silenced his critics when he came in sixth, only 5 seconds slower. Tour Boss Jean-Marie Leblanc said that the Voet problem didn't concern him or the Tour and that the authorities would sort things out. Bruno Roussel, the director of the Festina team expressed surprise over Voet's arrest.

The first stage was run under wet and windy conditions with Tom Steels, who had been tossed from the previous year's Tour for throwing a water bottle at another rider, winning the sprint. But the cold rain didn't cool down the Festina scandal. Police raided the team warehouse and found more drugs, including bottles labeled with specific rider's names. Roussel expressed yet more mystification at the events and said he would hire a lawyer to deal with all of the defamatory things that had been written about the team. The next day Erik Zabel was able to win the Yellow Jersey by accruing intermediate sprint time bonifications.

When the Tour returned to France on July 14 the minor news was that Casino rider Bo Hamburger was the new Tour leader. The big news was that Voet had started to really talk to the police and told them that he was acting on instructions from Festina team management. Roussel said he was "shocked". The next day things got still worse for Festina. Roussel and team doctor Eric Rijckaert were taken by the police for questioning. Leblanc continued to insist that the Tour was not involved with the messy Festina doings and if no offenses had occurred during the Tour, there would be no action taken to expel Festina.

While the race continued on its way to the Pyrenees with Stuart O'Grady now the leader, the first Australian in Yellow since Phil Anderson and the second ever, the Festina affair continued to draw all of the attention. The world governing body of cycling, the U.C.I., suspended Roussel. Both the Andorra-based Festina watch company and Leblanc continued to voice support for the team's continued presence in the race.

Stage 6, on July 15, turned the entire cycling world upside-down. Roussel admitted that the Festina team had systematized its doping. The excuse was that since the riders were doping themselves, often with terribly dangerous substances like perfluorocarbon (synthetic hemoglobin), it was safer to have the doping performed under the supervision of the team's staff. Leblanc reacted by expelling the team from the Tour. Then several Festina riders including Richard Virenque and Laurent Dufaux called a news conference, asserted their innocence and vowed to continue riding in the Tour.

There was still a race going on amid all of the Festina doings and the first real sorting came with the 58-kilometer time trial of stage 7. Ullrich again showed that against the clock he is an astounding rider. American Tyler Hamilton came in second and was only able to come within 1 minute, 10 seconds of the speedy German. Another American rider, Bobby Julich of the Cofidis team turned in a surprising third place, only 8 seconds slower than Hamilton. So now the General Classification with 2 more stages to go before the mountains:

- Jan Ullrich

- Bo Hamburger @ 1 minute 18 seconds

- Bobby Julich @ same time

- Laurent Jalabert @ 1 minute 24 seconds

- Tyler Hamilton @ 1 minute 30 seconds

Virenque announced that the Festina riders would not try to ride the Tour after their expulsion. That took Alex Zülle, World Champion Laurent Brochard, Laurent Dufaux and Christophe Moreau, among others, out of the action. The reaction from the Tour management, the team doctors and the fans was indicative of the blinders all parties were wearing. The Tour subjected 55 riders to blood tests and found no one with banned substances in his system. The Tour then declared that this meant that the doping was confined to a few bad apples. What it really meant was that for decades the riders and their doctors had learned how to dope so the drugs didn't show up in the tests. And, in 1998 there was no test for EPO. The team doctors protested that the Festina affair was bringing disrepute upon the other teams and their profession. The fans hated to see their beloved riders singled out and thought that Festina was getting unfair treatment. Officials, reflecting upon the easy ride TVM had received in March when their drug-laden car was found, reopened that case.

Stage 10, the long anticipated showdown between Ullrich and Pantani, had finally arrived. It was a Pyrenean stage, going from Pau to Luchon with the Aubisque, the Tourmalet, the Aspin and the Peyresourde. With no new developments in the drug scandals, the attention could finally be focused on the sport of bicycle racing. It was cold and wet in the mountains, which saps the energy of the riders as much as or more than a hot day. It was on the Peyresourde that the action finally started. Casino rider Rudolfo Massi was already off the front. Ullrich got itchy feet and attacked the dozen or so riders still with him. Pantani responded with his own attack and was gone. Pantani closed to within 36 seconds of Massi after extending his lead on the descent of the Peyresourde. Ullrich and 9 others including Julich came in a half-minute after Pantani. After losing the lead in stage 8 when a break of non-contenders was allowed to go, Ullrich was back in Yellow. Pantani was sitting in eleventh place, 4 minutes, 41 second back.

Stage 11, July 22, had 5 climbs rated second category or better with a hilltop finish at Plateau de Beille, an hors category climb new to the Tour. As usual, the best riders held their fire until the final climb. Ullrich flatted just before the road began to bite but was able to rejoin the leaders before things broke up. And break up they did when Pantani took off and no one could hold his wheel. Ullrich was left to chase with little help as he worked to limit his loss. At the top Pantani was first with the Ullrich group a minute and a half back. While Pantani said he was too tired from the Giro to consider winning the Tour, he was slowly closing the gap.

After the Pyrenees and with a rest day next, the General Classification stood thus:

- Bobby Julich @ 1 minute 11 seconds

- Laurent Jalabert @ 3 minutes 1 second

- Marco Pantani @ same time

Festina director Roussel, still in custody, issued a public statement accepting responsibility for the systematic doping within the team.

On July 24, the day of stage 12, the heat in the doping scandal was raised a bit more, if that were possible. Three more Festina team officials including the 2 assistant directors were arrested. A Belgian judge performing a parallel investigation found computer records of the Festina doping program on Erik Rijckaert's computer. Rijckaert said that the Festina riders all contributed to a fund to purchase drugs for the team. Six Festina riders were rounded up and questioned by the Lyon police: Zülle, Dufaux, Brochard, Virenque, Pascal Herve and Didier Rous. The scandal grew larger. TVM manager Cees Priem, the TVM team doctor and mechanic were arrested. A French TV reporter said that he had found dope paraphernalia in the hotel room of the Asics team.

So how did the riders handle this growing stink? Much as they did when they were caught up in the Wiel's affair in 1962. They became indignant. They were furious that the Festina riders had been forced to strip in the French jail and fuming that so much attention was focused on the ever-widening doping scandal instead of the race. In 1962 Jean Bobet talked the riders out of making themselves ridiculous by striking over being caught red-handed. There was no such voice of sanity in 1998. The riders initiated a slow-down, refusing to race for the first 16 kilometers.

On July 25 several Festina riders confessed to using EPO, including Armin Meier, Laurent Brochard and Christophe Moreau. The extent of the concern over the drug scandal was made clear when the French newspaper Le Monde editorialized that the 1998 Tour should be cancelled. It's important to note that what should have been outrage from the riders of the peloton, when confronted with the undeniable fact that they were racing against cheaters, was never voiced. Instead, the peloton defended the cheaters. When pro racers start screaming that they were robbed by the dopers then we may start to think that there has been some reform in the peloton. Until then, the pack is guilty.

As the Tour moved haltingly towards the Alps the top echelons of the General Classification remained unchanged. Alex Zülle issued a statement of regret admitting his use of EPO, saying what any rational observer should have assumed, that Festina was not the only team doping.

On Monday, July 27 the Tour reached the hard alpine stages. Stage 15 started in Grenoble and went over the Croix de Fer, the Télégraphe, and the Galibier to a hilltop finish at Les Deux Alpes. It was generally surmised that if Ullrich could stay with Pantani until the final climb he would be safe because the climb to Les Deux Alpes averages 6.2% with an early section of a little over 10% gradient. Ullrich's big-gear momentum style of climbing would be well suited to this climb.

Pantani didn't wait for the last climb. On the Galibier he exploded and quickly disappeared up the mountain. At the top he had 2½ minutes on Ullrich. On the descent Pantani used his superb descending skills to increase his lead on the now isolated Ullrich. By the start of the final ascent Pantani had a lead of more than 4 minutes. On the climb to Les Deux Alpes Ullrich's lack of deep, hard conditioning made itself manifest. He was in trouble and needed teammates Riis and Udo Bolts to pace him up the mountain. At the top of the mountain the catastrophe (as far as Telekom was concerned) was complete. Pantani was in Yellow, having taken almost 9 minutes out of the German who came in twenty-fifth that day. The new General Classification shows how dire Ullrich's position was:

- Marco Pantani

- Bobby Julich @ 3 minutes 53 seconds

- Fernando Escartin @ 4 minutes 14 seconds

- Jan Ullrich @ 5 minutes 56 seconds

Stage 16 was the last day of truly serious climbing with the Porte, Cucheron, Granier, Gran Cucheron and the Madeleine. On the final climb Ullrich showed that he was doing much better than the day before when he attacked and only Pantani could go with him. Since Pantani was the leader and had the luxury of riding defensively, he let Ullrich do all the work. If Ullrich couldn't drop Pantani, he could at least put some distance between himself and Julich and Escartin, which he did. Pantani and Ullrich came in together with Ullrich taking the stage victory in Albertville. Julich and Escartin followed the duo by 1 minute, 49 seconds. Ullrich was back on the General Classification Podium:

- Bobby Julich @ 5 minutes 42 seconds

- Fernando Escartin @ 6 minutes 3 seconds

On Wednesday July 29, stage 17, the riders staged a strike. They started by riding very slowly and at the site of the first intermediate sprint they sat down. After talking with race officials they took off their numbers and rode slowly to the finish in Aix-les-Bains with several TVM riders in the front holding hands to show the solidarity of the peloton. If the reader thinks that the other members of the peloton did not know that the TVM team was doping I have ocean-front land in Arkansas for him to buy. Along the way the Banesto, ONCE and Risso Scotti teams abandoned the Tour. The Tour organization voided the stage allowing those riders who were members of teams that had not officially abandoned to start on Thursday.

Why all this anger now? First of all, the day before drugs were said to be found in a truck belonging to the Big Mat Auber 93 team. The next day this turned out to be untrue. Then the entire TVM squad was taken into custody and the team's cars and trucks were seized. They, like the Festina team, were handled roughly by the police, sparking outrage from the riders not yet in jail.

Thursday, July 30, stage 18: Kelme and Vitalicio Seguros quit the Tour. That made all 4 Spanish teams out. Rudolfo Massi, winner of stage 10 was taken into custody. At the start of the stage there were now only 103 riders left in the peloton, down from 189 starters.

Friday, July 31, stage 19. TVM abandoned the Tour. It turned out that ONCE's team doctor Nicolas Terrados was also put under arrest after a police search found drugs on their bus that later turned out to be legal.

So now it was Ullrich's last chance to take the Tour with the stage 20 52-kilometer individual time trial. Pantani was too good, losing only 2 minutes and 35 seconds to Ullrich. That sealed the Tour for Pantani. Ullrich acknowledged that he had not taken his preparation for the Tour seriously and paid a very high price for his lack of discipline. Sounding a note that will become a metaphor for the balance of his career, he promised to work harder in the future and not repeat his mistakes.

Of 189 starters in this Tour, 96 finished.

Final 1998 Tour de France General Classification:

- Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno): 92 hours 49 minutes 46 seconds

- Jan Ullrich (Telekom) @ 3 minutes 21 seconds

- Bobby Julich (Cofidis) @ 4 minutes 8 seconds

- Christophe Rinero (Cofidis) @ 9 minutes 16 seconds

- Michael Boogerd (Rabobank) @ 11 minutes 26 seconds

Climbers' competition:

- Christophe Rinero: 200 points

- Marco Pantani: 175 points

- Alberto Elli: 165 points

Points competition:

- Erik Zabel: 327 points

- Stuart O'Grady: 230 points

- Tom Steels: 221 points

Pantani became the first Italian to win the Tour since Felice Gimondi in 1965. He became the seventh man to do the Giro-Tour double, joining Coppi, Anquetil, Merckx, Hinault, Roche and Indurain.

The drug busts of 1998 did little to alter rider and team behavior. There would be more drug raids and more outraged screams from the riders. But the police knew what they were dealing with. The riders had formed a conspiracy to cheat and to break the law. Their code of silence was nothing more than a culture of intimidation to allow the riders to do what they had done for more than 100 years, take drugs to relieve their pain, allow them to sleep and improve their performance. Their anger at the treatment they received from the police is indicative of their sense of entitlement, their feeling that this was something that they could and sometimes had to do. On the other hand cops like to catch bad guys and when they do, they aren't always gentle.

Now, there is one other question that needs to be asked. Voet, who had chosen a lightly-traveled road on his way to Calais, was expecting the customs station at the French frontier to be abandoned. It wasn't and he was stopped and searched by border agents who seemed to be waiting for him. Roussel believes that when Tour Boss Jean-Marie Leblanc, who is conservative politically, talked Roussel into letting Bernadette Chirac, wife of conservative French President Jacques Chirac, do a bit of self-promotion when she visited the Tour for stage 7, the Tour became a target in the war between France's Right and the Left. The left-center coalition government had given the Ministry for Sports and Youth to the left-leaning Marie-George Buffet. Roussel hypothesized that Festina, Leblanc and the Tour were sacrificed to give Buffet a victory against the Right and incidentally, against doping. Certainly it was clear after the 1998 Tour that systematized doping was part of the professional cycling scene and had been that way for some time. Roussel asks why did this festering problem erupt into scandal at this point? A deeper exploration of the subject is beyond the intended scope of this book.

If the reader is interested I recommend Les Woodland's The Crooked Path to Victory where the complex subject of sport, politics, dope and the 1998 Tour is brilliantly dissected.

© McGann Publishing

- Tour de France

- Giro d'Italia

- La Vuelta ciclista a España

- World Championships

- Amstel Gold Race

- Milano-Sanremo

- Tirreno-Adriatico

- Liège-Bastogne-Liège

- Il Lombardia

- La Flèche Wallonne

- Paris - Nice

- Paris-Roubaix

- Volta Ciclista a Catalunya

- Critérium du Dauphiné

- Tour des Flandres

- Gent-Wevelgem in Flanders Fields

- Clásica Ciclista San Sebastián

- INEOS Grenadiers

- Groupama - FDJ

- EF Education-EasyPost

- Decathlon AG2R La Mondiale Team

- BORA - hansgrohe

- Bahrain - Victorious

- Astana Qazaqstan Team

- Intermarché - Wanty

- Lidl - Trek

- Movistar Team

- Soudal - Quick Step

- Team dsm-firmenich PostNL

- Team Jayco AlUla

- Team Visma | Lease a Bike

- UAE Team Emirates

- Arkéa - B&B Hotels

- Alpecin-Deceuninck

- Grand tours

- Countdown to 3 billion pageviews

- Favorite500

- Profile Score

- Stage winners

- All stage profiles

- Race palmares

- Complementary results

- Finish photo

- Contribute info

- Contribute results

- Contribute site(s)

- Results - Results

- Info - Info

- Live - Live

- Game - Game

- Stats - Stats

- More - More

- »

Race information

- Date: 02 August 1998

- Start time: -

- Avg. speed winner: 39.27 km/h

- Race category: ME - Men Elite

- Distance: 147 km

- Points scale: GT.A.Stage

- Parcours type:

- ProfileScore: 22

- Vert. meters: 1593

- Departure: Melun

- Arrival: Paris

- Race ranking: 0

- Startlist quality score: 1692

- Won how: Sprint of large group

- Avg. temperature:

Grand Tours

- Vuelta a España

Major Tours

- Volta a Catalunya

- Tour de Romandie

- Tour de Suisse

- Itzulia Basque Country

- Milano-SanRemo

- Ronde van Vlaanderen

Championships

- European championships

Top classics

- Omloop Het Nieuwsblad

- Strade Bianche

- Gent-Wevelgem

- Dwars door vlaanderen

- Eschborn-Frankfurt

- San Sebastian

- Bretagne Classic

- GP Montréal

Popular riders

- Tadej Pogačar

- Wout van Aert

- Remco Evenepoel

- Jonas Vingegaard

- Mathieu van der Poel

- Mads Pedersen

- Primoz Roglic

- Demi Vollering

- Lotte Kopecky

- Katarzyna Niewiadoma

- PCS ranking

- UCI World Ranking

- Points per age

- Latest injuries

- Youngest riders

- Grand tour statistics

- Monument classics

- Latest transfers

- Favorite 500

- Points scales

- Profile scores

- Reset password

- Cookie consent

About ProCyclingStats

- Cookie policy

- Contributions

- Pageload 0.0645s

2-FOR-1 GA TICKETS WITH OUTSIDE+

Don’t miss Thundercat, Fleet Foxes, and more at the Outside Festival.

GET TICKETS

BEST WEEK EVER

Try out unlimited access with 7 days of Outside+ for free.

Start Your Free Trial

Powered by Outside

Shock and Awe at the 1998 Tour de France: Marco Pantani and Bobby Julich

From grenoble to les deux alpes in the the years of pantani and jan ullrich..

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>Download the app .

Storm clouds loomed in Grenoble on Monday, July 27. And for once, on this Tour, they were literal rather than metaphorical. They hung low in the valley, obscuring the mountains. It was gloomy and bitterly cold—53°F in the valley, 39°F at the summits of the four mountains on the itinerary: the Col de la Croix de Fer, Col du Télégraphe, Col du Galibier, and Les Deux Alpes. Hard enough without the cold and the rain.

It was the first of three days in the Alps, the second and final summit finish of this Tour. Marco Pantani ’s last chance. Il Pirata was still a distant fourth, three minutes behind Jan Ullrich, with Laurent Jalabert and Bobby Julich equal second, just over a minute down. But today would not be Pantani’s day, as far as Julich was concerned—it would be his. “I had a battle plan. I definitely looked on that day as my opportunity. I was so close to that jersey for two weeks and never got to touch it. This was the day I thought I had it.”

It was miserable in Grenoble and would be treacherous in the mountains. The riders were reluctant to leave the team buses, and when they appeared they wore arm warmers, rain jackets, and gloves, with more layers stuffed in pockets. In a subdued mood, they got under way, Rodolfo Massi leading over the top of the Croix de Fer after 30 km of climbing. By now conditions were deteriorating. The temperature plummeted and the rain turned to hail as they climbed toward 2,000 m (6,500 feet). And there was a crash, Daniele Nardello tumbling off the road, taking Pantani down with him—but he was quickly back up. Julich tried to use the climb as a launch pad for a long-range attack, believing that it was worth a tentative jab. Ullrich and his team might not regard him as a serious rival, and let him go. But Ullrich seemed nervous; at his instruction, his Telekom teammates brought Julich back. When Julich was caught, his Cofidis teammate Christophe Rinero countered. He got away and was joined by Massi, Marcos-Antonio Serrano, and José María Jiménez.

Behind, Ullrich’s Telekom team rode hard to control the race in the valley between the Croix de Fer and the Télégraphe, which acted as a first step to the monstrous Galibier. When the road began to climb again, Luc Leblanc became aggressive. And Ullrich seemed worried, reacting to his accelerations with nervous urgency. It was ominous. The final climb was still to come, yet here was the yellow jersey riding hard to chase down the 31-year-old former world champion, whose best days were behind him.

Clearly Ullrich was anxious. He was also now isolated, his teammates having paid for their riding in the valley.

As Ullrich chased down Leblanc, Julich came up more steadily, followed by Pantani and the rest. There was a regrouping; eight riders bunched together, as though for shelter. It was a brief lull. The next to dart off the front was the Spaniard Fernando Escartín. No reaction; the Ullrich group was still catching its breath after Leblanc’s attack. They fanned across the road as more riders came up from behind to swell their numbers, including reinforcements for Ullrich and Julich in Bjarne Riis and Kevin Livingston.

The climb eased. “It was almost a false flat, but definitely still climbing—a bit of respite,” says Julich. “And I remember Kevin, once he came back up to the group, going straight to the front. He started to go hard; instead of smoothly bringing it up, he kind of attacked. And I yelled at him, ‘Slow down!’ And he looked back at me; he was in full race mode. He was kind of pissed at me.”

Leblanc went again, pressing hard on the front, stringing it out. Ullrich marked the move; Pantani tucked in behind. It was as close as Pantani had been to the front; he had been riding unusually conservatively until now.

Then he goes. With the muck and grime from the road clinging to his pale Mercatone Uno team clothing, Pantani looks like a little chimney sweep, with his goatee beard, a bandanna knotted at the back of his head, and a small diamond-encrusted gold hoop in his ear. It was a carefully cultivated look, a disguise, a mask, amounting to an effort by Pantani to overcome years of self-consciousness about his appearance. His hair had started falling out when he was 15 and he was conspicuously bald by his early twenties. His ears also stuck out, inspiring unkind nicknames, including “Elephantino.” Eventually, he would resort to surgery and have his ears pinned back. But for now the bandanna did the job.

He has this... smile on his face. I’ll never forget it.

Implausibly, on this gloomiest of days, Il Pirata is wearing dark glasses with yellow frames, matching the flashes of yellow on his Bianchi bike and clothing, and his all-yellow shoes and tires.

“He makes this jump,” says Julich. “It’s, like, come on! What? Here I am telling my teammate to slow down and he just blasts past. He goes about 15 pedal strokes and then he turns around and looks back and he has this… smile on his face. I’ll never forget it. This smile. And I thought, now he’s going to slow up.”

Julich was wrong. Out of the saddle, hands on the drops, Pantani, having watched Ullrich use his strength to chase down Leblanc, sprints hard.

He would use a single bullet, not a scatter gun: one devastating acceleration rather than a flurry of attacks. Eight seconds later he glanced back while still pedaling. Two seconds later he paused, freewheeled, stood on the pedals, twisted his body to the right, angling his head back down the road—a long, lingering glance. He wasn’t slowing down. He was surveying the wreckage. No wonder he was smiling.

Luc Leblanc tried to go after him. He almost made it. But there was no catching Pantani. Once on his own, Il Pirata removed his dark glasses and rolled down his arm warmers. He was going to work. The loose ends of his bandanna flapped at the back of his head as he sprinted up the climb, hands in the hooks of the handlebars. There were 5.5 km to the top of the 2,645-meter Galibier. “Up there, I could see the weather setting in,” says Julich, “and I thought, this is going to be nuts.”

Even in mild weather, the Galibier was fearsome. Jaksche had been given some advice by his team leader, Leblanc. “Luc helped me a lot,” says Jaksche, “and on the Galibier I came up to that front group before Pantani took off. Luc said, ‘Never look to the left or the right; just look at the road.’ I said, ‘Why?’ Then I looked. ‘Ah, I see.’”

The five riders ahead of Pantani—Escartín on his own, and ahead of him the four-man break of Rinero, Massi, Serrano, and Jiménez—were his prey. Their labored efforts reflected the dismal conditions while Pontoon’s defied them. Rain spattered the lens of the TV camera, distorting the image, turning the road slick and black, but Pantani appeared to be gliding up it. Behind, meanwhile, Ullrich sat at the front and looked around for help. Julich pulled alongside but offered none. Up front, Pantani caught and passed Escartín. Then Ullrich’s team car accelerated to the front of the chasing group, warning the rider in yellow not to do too much work; there was still a long way to go, and the cold sapped strength and energy as effectively as the gradient.

Ahead, Pantani went through the breakaway like a hot knife through butter. Jiménez, the handsome and enigmatic Spanish climber known as “El Chava,” clung to his rear wheel. The image of this pair together on the upper slopes of this rain-lashed mountain is poignant because, these days, they are often mentioned in the same breath, as tragic icons of the destructive power of drugs. Like Pantani, Jiménez would enter a downward spiral of despair and depression. He died two months before Pantani, in December 2003. He was 32, Pantani 34.

Toward the summit of the Galibier, Jiménez was dropped by Pantani, who then caught Rinero. Then El Chava got his second wind and sprinted back up to Pantani’s rear wheel, the effort visible in his heaving rib cage. But Pantani rose out of the saddle once more and crossed the summit of the Galibier alone, grabbing a rain jacket from one of his directeurs sportifs, Orlando Maini, who had jumped out of the car and was waiting for him. He tried to put it on, on the move, but couldn’t. He stopped, allowing Jiménez to pass him; they would team up again on the descent.

He looked absolutely frozen.

Julich crested the summit at the head of the chasing group, two minutes behind Pantani, knowing that the long descent would be more crucial than in normal conditions. “Climbing the Galibier in that lead group, we were all just kinda stuck in mud. There were none of us who could do anything. Pantani was gone. We were just chopping wood trying to get up that climb.

“But I knew the descent was going to be important. And from the limited experience I had, I knew I had to get my rain jacket on before we started the descent. I had my Gore-Tex jacket in my back pocket; I had gone back and got it from the team car on the Télégraphe, before we started on the Galibier. I remember thinking to myself, OK, Bobby, if you have to stop at the top to put on your rain jacket then do it; and zip it up, make sure it’s on.

“But I got caught up in the moment because guys were taking bottles and feeds, and we crested the top so quickly and you start the descent. So I thought, oh no, I’m not going to stop, I’ll get this on while I’m riding.” That was easier said than done; Julich’s hands were numb from the cold.

He couldn’t operate the zipper, nor could he react quickly when he realized he was heading too fast into the first hairpin bend. Ahead of him was a camper van. He careened off the road. “I almost ended up smashing into that camper van. I went round the front of it. I had my hands off the bars, and when I went to hit the brakes, in that weather the brake pads weren’t working very well.

“I had meant to stop anyway, so I thought, I’ll stop here and put it on. But then the guy who had the camper van, he jumped up and pushed me back on my bike before I was ready! I hadn’t got my jacket on; I was still trying to zip it up. That made me panic a bit. Once I got going, finally I got it zipped up, and then I remember catching the group and looking over at Jan.” Ullrich, almost alone among the overall contenders, opted not to put on a rain jacket. “He had these arm warmers on,” says Julich, “and this vest, and he had a bottle in his mouth; he was holding it with his teeth. I looked over at him and he looked absolutely frozen. I was freezing even with my jacket on. You couldn’t go round the turns because you were shaking so bad.”

Now, says Julich, it was no longer a bike race. It was a game of self-preservation. A game that Ullrich was evidently losing. His upper body was locked, rigid. His face was puffy. Huge bags began to appear under his eyes.

Jörg Jaksche recalls, “It was not really a race anymore. It was just about trying to survive.” He says that his countryman Ullrich suffered even more in the cold because—ironically, given the attention paid to his weight—he was so skinny. But Jaksche has another theory about why Ullrich struggled so badly that day. “It sounds silly, but the Italians didn’t have only Power Bars for race food. This is a crucial moment,” says Jaksche. “And Ullrich’s team, Telekom, they had all this technical race food—the Power Bars. But they are shit when it’s cold. You can’t eat them. They turn into bricks.

“On the Italian teams, we ate small paninis with marmalade or honey or Nutella. Not so sophisticated, maybe, but better in those conditions. And I think this is one reason why Jan had such a bad time.”

Pantani rode most of the descent with Jiménez, though El Chava struggled for much of it with his rain jacket, trying to close the zipper. Pantani urged him through as they plummeted together. Pantani drank from his bottle and ate his paninis from his pocket: coal on the fire for later. He slipped his dark glasses back on. Further down they were joined by some of the other survivors from the break: Serrano, Rinero, Massi, and also Escartín. Strength in numbers. They were companions for Pantani to the base of the final climb, to the ski station at Les Deux Alpes. The gap opened to three minutes; it made Pantani maillot jaune virtuel, the yellow jersey on the road.

I gave everything and risked everything.

Julich recalls, “When you get to the bottom, there’s a long valley with the tunnels before you get to Les Deux Alpes. By that time I started to get pretty warm; I had the jacket zipped up. And I was like, OK, it’s on, here’s the last climb, here we go. I was trying to get the guys to work but everyone was just frozen solid. I was with Jalabert in a little group at the base of the climb, and all of a sudden I saw him ripping off all his clothes, and I thought, I’m gonna do the same thing. It was like a garage sale at the bottom of that climb. Gloves, arm warmers, my Gore-Tex jacket, which had just saved my life. All on the side of the road.”

All except Ullrich, who had nothing to remove. Then, as if things couldn’t get worse for him, he punctured. He pulled to the right side of the road, stuck his hand in the air, and his team car pulled up behind him. He was alone. There were no teammates in his group. The timing was terrible. They were about to start climbing again. A similar thing had happened to Ullrich on the approach to Plateau de Beille, over a week earlier, and he had ridden hard to regain the group and move to its head—overdoing it, and paying for the effort later when Pantani rode away. Now, though, frozen to the core, teeth clamped shut to prevent shivering, it was impossible for him even to rejoin the group. He got back into the convoy of vehicles following Julich’s group, but couldn’t make contact. Later, he was joined by a couple of teammates, Bolts and Riis. But he struggled to stay with them. He ripped off the yellow vest he had put on as token resistance to the cold, throwing it angrily to the road, then tried to hold the wheels of his teammates. The camera zoomed in on him, showing his puffy face, the bulging bags under his eyes.

Julich didn’t know Ullrich had punctured. All he knew was that he had gone. Last he heard, Pantani was a couple of minutes up the road. Now the yellow jersey was his for the taking. “Right away, I went. At the foot of the climb. I knew the climb. We had done it in a recon camp before the Tour. I knew it wasn’t a very steep climb, that it was good for me. A minute later I took off my helmet, gave it to the motorcycle guy, the Mavic support motorbike. It’s funny, my dad always told me to wear my helmet. Then I was just going in full time trial mode, just hoping Jan didn’t come around me. I had no idea where he was.

“I was so cold, I could only push a massive gear. I couldn’t spin, couldn’t turn my legs fast, but it was just one of those times you felt mind over matter. Mentally, it was, come on, all the way to the line, all the way to the line.” Julich felt that he was closing the gap on Pantani—or rather, that he must be, because he was feeling so strong. He was more concerned with the whereabouts of Ullrich than Pantani. “I was thinking of Jan, because he was in yellow.

“No one passed me the entire climb, and I felt like I was going, really going. I dropped everyone apart from [Michael] Boogerd, who came across and stayed on my wheel. I was thinking, holy cow. And when I came across the line, I thought I’d taken the jersey. I assumed I’d taken the jersey.”

Pantani had dropped his companions as soon as the road began to rise.

They were blown away as he sprinted up the climb, hands on the drops, out of the saddle almost the entire way. Pantani appeared to flatten the gradient, going so fast into hairpins that he needed all the road. He reached the finish in five hours, 43 minutes, 45 seconds, sprinting all the way until just before the line, when he sat up, threw his head back, closed his eyes, and spread his arms. He had crucified his opponents. But watching it now, this glimpse of Pantani in his Jesus-on-the-Cross pose is chilling. It is the defining image of Pantani, the one that, a few short years later, would be on the cover of the posthumous biography, The Death of Marco Pantani .

“When I attacked, I gave everything and risked everything,” said Pantani after the stage. “It was incredibly hard. It’s terrible to think afterward about how much you suffer in an attack like that.”

He dedicated his win to Luciano Pezzi, his mentor, who had died, at age 77, just days before the Tour began in Dublin. The highlight of Pezzi’s relatively modest racing career was a stage win at the 1955 Tour de France. Like Pantani at Les Deux Alpes, his success had also come on the 15th stage.

Adapted from Etape: 20 Great Stages from the Modern Tour de France by Richard Moore with permission of VeloPress.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Marco Pantani, 1998 Tour de France Winner, Is Dead at 34

By Samuel Abt

- Feb. 16, 2004

The headline in yesterday's Gazzetta dello Sport, the Italian daily sports newspaper, said of the death of Marco Pantani, the wayward champion of bicycle racing: "Lost Hero, We Adored You."

Pantani, 34, was found dead Saturday in a hotel in the Adriatic city of Rimini, Italy.

The magistrate investigating his death said yesterday that Pantani did not commit suicide, Reuters reported. But the magistrate, Paolo Gengarelli, told Reuters that no cause would be determined until after an autopsy, which was to be performed today.

He had not raced for almost a year, and then only after a year of near inactivity. He checked into a clinic to treat depression early last year and emerged after two weeks. He gained about 20 kilograms, or 44 pounds, to the 60 kilograms (about 133 pounds) he used to carry when he was climbing mountains with ease.

"Forget about Pantani the cyclist," he advised his fans in a rare interview in the fall. As the new season started this month, he belonged to no team.

Increasingly withdrawn, he spent part of the winter traveling in South America, shedding some weight and considering a return to the sport.

"For him, it's all or nothing," Pantani's father, Paolo, told procycling, the British magazine. "For that reason, I'm pessimistic" about any comeback.

Father and son were close and spent Christmas together. Pantani had no wife or children and, at least recently, few intimate friends.

When he won the Giro d'Italia and the Tour de France back to back in 1998 — the first Italian to win the Tour in 33 years — he became a major star.

A year later, he began his descent. On the next-to-last day of the Giro, the sport's second-ranked race behind the Tour de France, Pantani was wearing the leader's pink jersey when drug inspectors visited him.

He was found to have an abnormally high reading of red blood cells, an indication, if not proof, of the use of performance-enhancing drugs. On the spot, he was ousted from the competition.

In the Gavia Pass in the Alps, a major climb in the Giro at 2,621 meters high, or about 8,600 feet, a crowd estimated at 200,000 waited vainly the next day to cheer for Pantani. When the word of his disqualification spread, fans were saddened and angry, the French sports newspaper L'Équipe reported.

"For me, it's the end of a dream," a man identified as Francesco, 65, said at the time. "He restored a sense of pride to Italy. But that's over now. He tricked us, and I can't forgive him."

The tifosi — the highly enthusiastic Italian fans — forgave everything done by Pantani, who was nicknamed Elefantino, or Dumbo, because of his big ears. He preferred to be called Il Pirata, the Pirate, and wore a gold earring with a bandana on his shaved head. He did have style, along with bounce and a big smile.

Lately, the past was closing in. He was accused in a handful of doping cases in addition to the 1999 Giro. He was found not guilty on technicalities but suspended once for six months. Another charge was pending in court.

In his words and manner, signs of depression were evident even before he entered the clinic. For years he had been quarreling with rival riders and team officials, which was in contrast to his popularity with them during his vintage years.

Sedatives were found near his bed Saturday night and "some thoughts" had been written on hotel stationery, the police said.

They were not a farewell note, a magistrate in Rimini said, adding that the sedatives were not illegal. Pantani had been a guest at the hotel for five days but was reportedly seen only at breakfast.

Among other riders paying tribute to Pantani yesterday was Miguel Indurain, the Spaniard who won the Tour de France five times in the 1990's.

In the Spanish sports daily Marca, he described Pantani as a "tragic genius."

"Apart from his undeniable quality as a rider, he got people hooked on the sport," Indurain said. "There may be riders who have achieved more than him, but they never succeeded in drawing in the fans as he did."

Referring to the failed drug test in the Giro, Indurain added: "It ended up complicating his whole life, and he was never able to get over it. He was never the same again."

Pantani took part in five Tours de France, winning in 1998 and finishing third in 1994 and 1997. He won eight daily stages, all in the Alps and the Pyrenees.

His last Tour was in 2000, when he won two stages, including the one up Mont Ventoux.

In the Giro, he was second in 1994 in addition to his victory. He won eight stages there, too, all in the mountains.

Cycling Around the Globe

The cycling world can be intimidating. but with the right mind-set and gear you can make the most of human-powered transportation..

Are you new to urban biking? These tips will help you make sure you are ready to get on the saddle .

Whether you’re mountain biking down a forested path or hitting the local rail trail, you’ll need the right gear . Wirecutter has plenty of recommendations , from which bike to buy to the best bike locks .

Do you get nervous at the thought of cycling in the city? Here are some ways to get comfortable with traffic .

Learn how to store your bike properly and give it the maintenance it needs in the colder weather.

Not ready for mountain biking just yet? Try gravel biking instead . Here are five places in the United States to explore on two wheels.

COLNAGO Mexico Oro, Campagnolo Super Record, 61cm (1977-78) – SOLD

BIANCHI XL EV2 Reparto Corse – M.Pantani Mercatone Uno replica (1999-00) – SOLD

BIANCHI Mega Pro XL Mercatone Uno – M.Pantani Tour de France ’98 replica – SOLD

Marco Pantani (13 January 1970 – 14 February 2004) widely considered as one of the best climbers of his era in professional road bicycle racing. He won both the Giro d’Italia and the Tour de France and in 1998 , is the last cyclist, and one of only seven, to win the Giro and the Tour in the same year . Pantani’s attacking style and aggressive riding turned him into a fan favorite in the late 1990s. He was known as “Il Pirata” (“The pirate”) because of his shaved head and the bandana and earrings he always wore. At 1.72 m and 57 kg , he had the classic build for a mountain climber .

Bianchi’s Reparto Corse (Bianchi’s Race Department) facility hand built frames for their top riders and of course Marco Pantani was one of them riding for Mercatone Uno sponsored by Bianchi . Their top model Mega Pro XL was made of exclusive set of Triple Butted SC61.10A heat treated shaped tubes. Aluminum was the material of choice back then, even some of his biggets rivals rode full carbon bikes.

Marco PANTANI attacked on Col du Galibier and took the yellow jersey and win the TDF 1998

Proudly presenting one of the most iconic bikes in cycling history, the Bianchi Mega Pro XL Mercatone Uno. It’s very similar to Marco Pantani’s bike on his way to winning Giro d’Italia and Tour de France back in 1998. The frame is shinning in beautiful mix of Bianchi and Mercatone Uno paintjob, build with Campagnolo Record Titanium 9s groupset from 1998, Campagnolo Shamal 12HPW Titanium wheels, PMP Titanium seatpost, Pantani’s personalized Selle Italia Flite titanium saddle, Time Equipe Mag pedals, titanium bottle cage, ITM Big One stem and ITM classic handlebar, so all exact components as used by Marco Pantani at the 1998 Tour de France .

Unique chance for all Pantani fans to get this amazing replica.

Frame / Fork : Bianchi Mega Pro XL Reparto Corse Mercatone Uno (SC61.10A)

-seat tube (c-t): 55 cm

-top tube (c-c): 54 cm

-headset tube: 11.2 cm

-standover: 77.7 cm

Wheelset : Campagnolo Shamal 12HPW Titanium

Crankset : Campagnolo Record (170mm ; 53/39)

Rear Derailleur : Campagnolo Record Titanium 9s

Front Derailleur : Campagnolo Record

Levers : Campagnolo Record Titanium 9s

Brakes : Campagnolo Record

Chain : Campagnolo C9

Pedals : Time Pro Equipe Mag

Stem : ITM Big One Mercatone Uno

Handlebar : ITM Super Italia Pro Classic

Seatpost : PMP Titanium (27,2mm)

Seat : Selle Italia Flite Titanium ”Il Pirata”

Tires : Michelin

Bottle cage : titanium

Bottle: Coca Cola Tour de France 1998. (original)

Handlebar tape : Bianchi, cork

Condition : Used, but good condition. No cracks, no dents, not bent. Some touch-ups signs of normal use. All parts are working fine.

PRICE: SOLD (January 2023)

Related products.

MASI Prestige, Campagnolo Super Record, 56.5cm (1979) – SOLD

Username or email *

Password *

Remember me Login

Lost your password?

Moscow, Russia

See the official Rolling Stones web site in Russia , also having info in English!

How "the rolling stones" solve the problem of unemployment in moscow, their own uncompetence, their own openess, thanks to constantin preobrazhensky (moscow) for supplying info about the web site and the stones show in russia. also thanks to leonid ulitsky , italy, for info..

The Comprehensive Guide to Moscow Nightlife

- Posted on April 14, 2018 July 26, 2018

- by Kings of Russia

- 8 minute read

Moscow’s nightlife scene is thriving, and arguably one of the best the world has to offer – top-notch Russian women, coupled with a never-ending list of venues, Moscow has a little bit of something for everyone’s taste. Moscow nightlife is not for the faint of heart – and if you’re coming, you better be ready to go Friday and Saturday night into the early morning.

This comprehensive guide to Moscow nightlife will run you through the nuts and bolts of all you need to know about Moscow’s nightclubs and give you a solid blueprint to operate with during your time in Moscow.

What you need to know before hitting Moscow nightclubs

Prices in moscow nightlife.

Before you head out and start gaming all the sexy Moscow girls , we have to talk money first. Bring plenty because in Moscow you can never bring a big enough bankroll. Remember, you’re the man so making a fuzz of not paying a drink here or there will not go down well.

Luckily most Moscow clubs don’t do cover fees. Some electro clubs will charge 15-20$, depending on their lineup. There’s the odd club with a minimum spend of 20-30$, which you’ll drop on drinks easily. By and large, you can scope out the venues for free, which is a big plus.

Bottle service is a great deal in Moscow. At top-tier clubs, it starts at 1,000$. That’ll go a long way with premium vodka at 250$, especially if you have three or four guys chipping in. Not to mention that it’s a massive status boost for getting girls, especially at high-end clubs.

Without bottle service, you should estimate a budget of 100-150$ per night. That is if you drink a lot and hit the top clubs with the hottest girls. Scale down for less alcohol and more basic places.

Dress code & Face control

Door policy in Moscow is called “face control” and it’s always the guy behind the two gorillas that gives the green light if you’re in or out.

In Moscow nightlife there’s only one rule when it comes to dress codes:

You can never be underdressed.

People dress A LOT sharper than, say, in the US and that goes for both sexes. For high-end clubs, you definitely want to roll with a sharp blazer and a pocket square, not to mention dress shoes in tip-top condition. Those are the minimum requirements to level the playing field vis a vis with other sharply dressed guys that have a lot more money than you do. Unless you plan to hit explicit electro or underground clubs, which have their own dress code, you are always on the money with that style.

Getting in a Moscow club isn’t as hard as it seems: dress sharp, speak English at the door and look like you’re in the mood to spend all that money that you supposedly have (even if you don’t). That will open almost any door in Moscow’s nightlife for you.

Types of Moscow Nightclubs

In Moscow there are four types of clubs with the accompanying female clientele:

High-end clubs:

These are often crossovers between restaurants and clubs with lots of tables and very little space to dance. Heavy accent on bottle service most of the time but you can work the room from the bar as well. The hottest and most expensive girls in Moscow go there. Bring deep pockets and lots of self-confidence and you have a shot at swooping them.

Regular Mid-level clubs:

They probably resemble more what you’re used to in a nightclub: big dancefloors, stages and more space to roam around. Bottle service will make you stand out more but you can also do well without. You can find all types of girls but most will be in the 6-8 range. Your targets should always be the girls drinking and ideally in pairs. It’s impossible not to swoop if your game is at least half-decent.

Basic clubs/dive bars:

Usually spots with very cheap booze and lax face control. If you’re dressed too sharp and speak no Russian, you might attract the wrong type of attention so be vigilant. If you know the local scene you can swoop 6s and 7s almost at will. Usually students and girls from the suburbs.

Electro/underground clubs:

Home of the hipsters and creatives. Parties there don’t mean meeting girls and getting drunk but doing pills and spacing out to the music. Lots of attractive hipster girls if that is your niche. That is its own scene with a different dress code as well.

What time to go out in Moscow

Moscow nightlife starts late. Don’t show up at bars and preparty spots before 11pm because you’ll feel fairly alone. Peak time is between 1am and 3am. That is also the time of Moscow nightlife’s biggest nuisance: concerts by artists you won’t know and who only distract your girls from drinking and being gamed. From 4am to 6am the regular clubs are emptying out but plenty of people, women included, still hit up one of the many afterparty clubs. Those last till well past 10am.

As far as days go: Fridays and Saturdays are peak days. Thursday is an OK day, all other days are fairly weak and you have to know the right venues.

The Ultimate Moscow Nightclub List

Short disclaimer: I didn’t add basic and electro clubs since you’re coming for the girls, not for the music. This list will give you more options than you’ll be able to handle on a weekend.

Preparty – start here at 11PM

Classic restaurant club with lots of tables and a smallish bar and dancefloor. Come here between 11pm and 12am when the concert is over and they start with the actual party. Even early in the night tons of sexy women here, who lean slightly older (25 and up).

The second floor of the Ugolek restaurant is an extra bar with dim lights and house music tunes. Very small and cozy with a slight hipster vibe but generally draws plenty of attractive women too. A bit slower vibe than Valenok.

Very cool, spread-out venue that has a modern library theme. Not always full with people but when it is, it’s brimming with top-tier women. Slow vibe here and better for grabbing contacts and moving on.

High-end: err on the side of being too early rather than too late because of face control.

Secret Room

Probably the top venue at the moment in Moscow . Very small but wildly popular club, which is crammed with tables but always packed. They do parties on Thursdays and Sundays as well. This club has a hip-hop/high-end theme, meaning most girls are gold diggers, IG models, and tattooed hip hop chicks. Very unfavorable logistics because there is almost no room no move inside the club but the party vibe makes it worth it. Strict face control.

Close to Secret Room and with a much more favorable and spacious three-part layout. This place attracts very hot women but also lots of ball busters and fakes that will leave you blue-balled. Come early because after 4am it starts getting empty fast. Electronic music.

A slightly kitsch restaurant club that plays Russian pop and is full of gold diggers, semi-pros, and men from the Caucasus republics. Thursday is the strongest night but that dynamic might be changing since Secret Room opened its doors. You can swoop here but it will be a struggle.

Mid-level: your sweet spot in terms of ease and attractiveness of girls for an average budget.

Started going downwards in 2018 due to lax face control and this might get even worse with the World Cup. In terms of layout one of the best Moscow nightclubs because it’s very big and bottle service gives you a good edge here. Still attracts lots of cute girls with loose morals but plenty of provincial girls (and guys) as well. Swooping is fairly easy here.