TYLER S. ROGERS, MD, MBA, FAAFP, AND BRENDAN LUSHBOUGH, DO, Martin Army Community Hospital, Fort Benning, Georgia

Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(2):187-190

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Key Clinical Issue

What are the risks and benefits of less frequent antenatal in-person visits vs. traditional visit schedules and televisits replacing some in-person antenatal appointments?

Evidence-Based Answer

Compared with traditional schedules of antenatal appointments, reducing the number of appointments showed no difference in gestational age at birth (mean difference = 0 days), likelihood of being small for gestational age (odds ratio [OR] = 1.08; 95% CI, 0.70 to 1.66), likelihood of a low Apgar score (mean difference = 0 at one and five minutes), likelihood of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission (OR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.50), maternal anxiety, likelihood of preterm birth (nonsignificant OR), and likelihood of low birth weight (OR = 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82 to 1.25). (Strength of Recommendation [SOR]: B, inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence.) Studies comparing hybrid visits (i.e., televisits and in-person) with in-person visits only did not find differences in rates of preterm births (OR = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.84 to 1.03; P = .18) or rates of NICU admissions (OR = 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82 to 1.28). (SOR: B, inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence.) There was insufficient evidence to assess other outcomes. 1

Practice Pointers

Antenatal care is a cornerstone of obstetric practice in the United States, and millions of patients receive counseling, screening, and medical care in these visits. 2 , 3 There is clear evidence supporting the benefits of antenatal care; however, the number of appointments needed and setting of visits is less understood.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends antenatal visits every four weeks until 28 weeks' gestation, every two weeks until 36 weeks' gestation, and weekly thereafter, which typically involves 10 to 12 visits. 4

Expert consensus and past meta-analyses have favored fewer antenatal care visits given similar maternal and neonatal outcomes. In 1989, the U.S. Public Health Service suggested a reduction in the antenatal visit schedule based on a multidisciplinary panel and expert opinion in conjunction with a literature review; however, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has not updated its guidelines, and practices have not changed. 5 A 2010 Cochrane review found no differences in perinatal mortality between patients randomized to higher vs. reduced antenatal care groups in high-income countries, and a 2015 Cochrane review showed no difference in neonatal outcomes for women in high-income countries. 6 , 7

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) review showed moderate- and low-strength evidence and did not find significant differences between traditional and abbreviated schedules when looking at many outcomes, such as gestational age at birth, low birth weight, Apgar scores, NICU admission, preterm birth, and maternal anxiety. The review was limited by a small evidence base with studies that are difficult to compare. The randomized controlled trials that were eligible were adjusted for confounding, whereas the nonrandomized controlled studies were not adjusted and were at high risk for confounding.

Telemedicine, defined as the use of electronic information and telecommunication to support health care among patients, clinicians, and administrators, is a new option for antenatal care delivery. 8 Televisits, the real-time communication between patients and clinicians via phone or the internet, are the specific interactions that encompass telemedicine. Recent literature suggests that supplementing in-person visits with televisits in low-risk pregnancies resulted in similar clinical outcomes and higher patient satisfaction scores. 9 The AHRQ review found no significant differences between rates of preterm births or NICU admissions for a hybrid model of televisits and in-person visits compared with in-person visits only. The review was limited due to the lack of adjustments for potential confounders in the study. For example, some of the studies were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which adds multiple confounders and potential for bias.

The AHRQ review offers limited opportunity for conclusions to suggest changes in current practice. The current evidence supports past evidence, suggesting that fewer visits are not associated with neonatal or maternal harm, and televisits may have a role in antenatal care. Many of the other outcomes of interest had insufficient evidence to generate conclusions.

Editor's Note: American Family Physician SOR ratings are different from the AHRQ Strength of Evidence ratings.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

For the full review, go to https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/product/pdf/cer-257-antenatal-care.pdf .

Balk EM, Konnyu KJ, Cao W, et al. Schedule of visits and televisits for routine antenatal care: a systematic review. Comparative effectiveness review no. 257. (Prepared by the Brown Evidence-Based Practice Center under contract no. 75Q80120D00001.) AHRQ publication no. 22-EHC031. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; June 2022. Accessed October 1, 2022. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/related_files/cer-257-antenatal-care-evidence-summary.pdf

Kirkham C, Harris S, Grzybowski S. Evidence-based prenatal care: part I. General prenatal care and counseling issues. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71(7):1307-1316.

Zolotor AJ, Carlough MC. Update on prenatal care. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(3):199-208.

Kriebs JM. Guidelines for perinatal care, sixth edition: by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55(2):e37.

Rosen MG, Merkatz IR, Hill JG. Caring for our future: a report by the expert panel on the content of prenatal care. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77(5):782-787.

Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(10):CD000934.

Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(7):CD000934.

Fatehi F, Samadbeik M, Kazemi A. What is digital health? Review of definitions. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2020;275:67-71.

Cantor AG, Jungbauer RM, Totten AM, et al. Telehealth strategies for the delivery of maternal health care: a rapid review. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(9):1285-1297.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) conducts the Effective Health Care Program as part of its mission to produce evidence to improve health care and to make sure the evidence is understood and used. A key clinical question based on the AHRQ Effective Health Care Program systematic review of the literature is presented, followed by an evidence-based answer based on the review. AHRQ’s summary is accompanied by an interpretation by an AFP author that will help guide clinicians in making treatment decisions.

This series is coordinated by Joanna Drowos, DO, MPH, MBA, contributing editor. A collection of Implementing AHRQ Effective Health Care Reviews published in AFP is available at https://www.aafp.org/afp/ahrq .

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2023 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

We use cookies. Read more about them in our Privacy Policy.

- Accept site cookies

- Reject site cookies

Search results:

- Afghanistan

- Africa (African Union)

- African Union

- American Samoa

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Bolivia (Plurinational State of)

- Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- British Virgin Islands

- Brunei Darussalam

- Burkina Faso

- Cayman Islands

- Central Africa (African Union)

- Central African Republic

- Channel Islands

- China, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- China, Macao Special Administrative Region

- China, Taiwan Province of China

- Cook Islands

- Côte d'Ivoire

- Democratic People's Republic of Korea

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Dominican Republic

- Eastern Africa (African Union)

- El Salvador

- Equatorial Guinea

- Falkland Islands (Malvinas)

- Faroe Islands

- French Guiana

- French Polynesia

- Guinea-Bissau

- Humanitarian Action Countries

- Iran (Islamic Republic of)

- Isle of Man

- Kosovo (UNSCR 1244)

- Lao People's Democratic Republic

- Liechtenstein

- Marshall Islands

- Micronesia (Federated States of)

- Netherlands (Kingdom of the)

- New Caledonia

- New Zealand

- North Macedonia

- Northern Africa (African Union)

- Northern Mariana Islands

- OECD Fragile Contexts

- Papua New Guinea

- Philippines

- Puerto Rico

- Republic of Korea

- Republic of Moldova

- Russian Federation

- Saint Barthélemy

- Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- Saint Martin (French part)

- Saint Pierre and Miquelon

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Sao Tome and Principe

- Saudi Arabia

- Sierra Leone

- Sint Maarten

- Solomon Islands

- South Africa

- South Sudan

- Southern Africa (African Union)

- State of Palestine

- Switzerland

- Syrian Arab Republic

- Timor-Leste

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Turkmenistan

- Turks and Caicos Islands

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United Republic of Tanzania

- United States

- Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of)

- Virgin Islands U.S.

- Wallis and Futuna

- Western Africa (African Union)

Search countries

Search for data in 245 countries

- SDG Progress Data

- Child Marriage

- Immunization

- Benchmarking child-related SDGs

- Maternal and Newborn Health Disparities

- Continuity of essential health services

- Country profiles

- Interactive data visualizations

- Journal articles

- Publications

- Data Warehouse

- Antenatal care

- Current status

- Available data

- Recent resources

Notes on the data

Antenatal care is essential for protecting the health of women and their unborn children.

Through this form of preventive health care, women can learn from skilled health personnel about healthy behaviours during pregnancy, better understand warning signs during pregnancy and childbirth, and receive social, emotional and psychological support at this critical time in their lives. Through antenatal care, pregnant women can also access micronutrient supplementation, treatment for hypertension to prevent eclampsia, as well as immunization against tetanus. Antenatal care can also provide HIV testing and medications to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. In areas where malaria is endemic, health personnel can provide pregnant women with medications and insecticide-treated mosquito nets to help prevent this debilitating and sometimes deadly disease.

Globally, while 88 per cent of pregnant women access antenatal care with a skilled health personnel at least once, only two in three (69 per cent) receive at least four antenatal care visits. In regions with the highest rates of maternal mortality, such as Western and Central Africa and South Asia, even fewer women received at least four antenatal care visits (56 per cent and 55 per cent, respectively). In viewing these data, it is important to remember that the percentages do not take into consideration the skill level of the healthcare provider or the quality of care, both of which can influence whether such care succeeds in bringing about improved maternal and newborn health.

Historical data show that the proportion of women receiving at least four antenatal care visits has increased globally over the last decade. The scale and pace of this progress, however, differs greatly by region. In Western and Central Africa, for example, only about half of pregnant women received four or more antenatal care visits between 2015 and 2021 (5 6 per cent). Stronger and faster progress is needed across all higher burden regions to drastically improve maternal and newborn outcomes.

Disparities in antenatal care coverage

Despite progress being made, large regional and global disparities in women receiving at least four antenatal care visits are observed by residence and wealth. Women living in urban areas are more likely to receive at least four antenatal care visits than those living in rural areas, with an urban-rural gap of 20 percentage points (79 per cent and 59 per cent, respectively). In addition, antenatal care coverage increases with wealth, with those in the richest quintile being almost twice as likely to receive at least four antenatal care visits than those in the poorest quintile, with a wealth gap of 29 percentage points (78 per cent and 49 per cent, respectively).

UNICEF, 2019, Health y Mothers, Healthy Babies: Taking stock of maternal health , New York 2019.

World Health Organization, 2016, WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a p ositive pregnancy ex p erience 2016.

UNICEF, The State of the World’s Children 2023 , UNICEF, New York, 2023.

WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division, Trends in Maternal Mortality: 2000 to 2020 , WHO, Geneva, 2023.

Antenatal care coverage

Maternal and newborn health coverage, build and download your own customisable dataset, women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health country profiles and dashboards.

Renewing progress on women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health in the era of COVID-19

Ending preventable newborn deaths and stillbirths by 2030

Measurement and accountability for maternal, newborn and child health: Fit for 2030?

Measurement of reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health and nutrition

Maternal and Newborn Health Disparities country profiles

Every Newborn Action Plan: Country implementation tracking tool guidance note

Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A guide for essential practice

Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015

Definition of indicators

Antenatal care coverage (at least one visit) is the percentage of women aged 15 to 49 with a live birth in a given time period that received antenatal care provided by skilled health personnel (doctor, nurse or midwife) at least once during pregnancy.

Skilled health personnel refers to workers/attendants that are accredited health professionals – such as a midwife, doctor or nurse – who have been educated and trained to proficiency in the skills needed to manage normal (uncomplicated) pregnancies, childbirth and the immediate postnatal period, and in the identification, management and referral of complications in women and newborns. Both trained and untrained traditional birth attendants are excluded.

Antenatal care coverage (at least four visits) is the percentage of women aged 15 to 49 with a live birth in a given time period that received antenatal care four or more times. Available survey data on this indicator usually do not specify the type of the provider; therefore, in general, receipt of care by any provider is measured.

Antenatal visits present opportunities for reaching pregnant women with interventions that may be vital to their health and well-being and that of their infants. WHO recommends a minimum of four antenatal visits based on a review of the effectiveness of different models of antenatal care. WHO guidelines are specific on the content of antenatal care visits, which should include:

- blood pressure measurement

- urine testing for bacteriuria and proteinuria

- blood testing to detect syphilis and severe anaemia

- weight/height measurement (optional).

Measurement limitations. Receiving antenatal care during pregnancy does not guarantee the receipt of interventions that are effective in improving maternal health. Receiving antenatal care at least four times, which is recommended by WHO, increases the likelihood of receiving effective maternal health interventions during antenatal visits. Importantly, although the indicator for ‘at least one visit’ refers to visits with skilled health providers (doctor, nurse or midwife), ‘four or more visits’ refers to visits with any provider, since standardized global national-level household survey programmes do not collect provider data for each visit. In addition, standardization of the definition of skilled health personnel is sometimes difficult because of differences in training of health personnel in different countries.

Related Topics

- Delivery care

- Maternal mortality

- Newborn care

Join our community

Receive the latest updates from the UNICEF Data team

- Don’t miss out on our latest data

- Get insights based on your interests

The dataset you are about to download is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license.

Antenatal Care

Percent distribution of antenatal care by type of provider, and percentage of antenatal care from a skilled provider.

1) Percentage of women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years, distributed by highest type of provider of antenatal care for most recent birth.

2) Percentage of women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years receiving antenatal care from a skilled provider for the most recent birth.

Population base:

a) Women who have had a live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey (NR file)

b) Women who have had a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey (NR file)

c) Women who have had a live birth or a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey (NR file)

Time period: Two years preceding the survey

Numerators:

Number of women within the base population who:

1) were attended for antenatal care (ANC) for their last most recent live birth (m80 = 1) or stillbirth (m80 = 3), distributed according to the type of provider with the highest level of qualification (m2a – m2n = 1). (Note that types of providers and variables below are based on the standard DHS-8 questionnaire. Actual provider types and variables are survey specific but will be from the m2a–m2n series.) The types of providers are country specific but typically include:

a) Doctor (m2a = 1)

b) Nurse/midwife (m2b = 1)

c) Auxiliary midwife (m2c = 1)

d) Community health worker/fieldworker (m2i = 1)

e) Traditional birth attendant (m2g = 1)

f) Other (m2h = 1 or m2j = 1 or m2k = 1 or m2l = 1 or m2m = 1)

g) No ANC (m2n = 1)

2) Number of women receiving antenatal care from a skilled provider for the most recent most recent live birth (m80 = 1) or stillbirth (m80 = 3). The classification of skilled provider is also country specific, but typically includes providers such as Doctor, Nurse/midwife, and Auxiliary midwife (often m2a = 1 or m2b = 1 or m2c = 1, but depends on the survey)

Denominator: Number of women in each of the population bases:

a) Women who have had a live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey (m80 = 1 & p19 < 24)

b) Women who have had a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey (m80 = 3 & p19 < 24)

c) Women who have had a live birth or a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey (m80 = 1 or 3 & p19 < 24 )

Variables: NR file.

Calculation

During data collection respondents may mention more than one provider. The percent distribution by type of provider takes the highest type of provider from the list above and does not include other providers mentioned by the respondent.

For each type of provider, the numerator divided by the overall denominator, multiplied by 100.

Handling of Missing Values

"Don't know" or missing values on type of provider are excluded from numerators but included in denominators.

Notes and Considerations

Percent distribution adds up to 100 percent.

The category “Trained nurse/midwife” includes only medically trained and licensed personnel. Traditional birth attendants (also sometimes called midwives) are not considered skilled providers, whether trained or untrained.

The category “Traditional birth attendant/other” includes auxiliary health personnel and cases where the respondent did not know the level of qualification.

The category skilled provider typically includes doctor/nurse, midwife, and auxiliary midwife. The category ‘auxiliary midwife’ may or may not be considered skilled in providing ANC and should be adapted to reflect the country’s healthcare system as in most countries, not all cadres of health care professionals are considered “skilled” in providing ANC.

Footman, K., L. Benova, C. Goodman, D. Macleod, C. A. Lynch, L. Penn‐Kekana, and O. M. R. Campbell. 2015. "Using multi‐country household surveys to understand who provides reproductive and maternal health services in low‐and middle‐income countries: a critical appraisal of the Demographic and Health Surveys." Tropical Medicine & International Health , 20(5): 589-606.

Lawn, J. E., Blencowe, H., Waiswa, P. et al. Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet. 2016. 387(10018), 587-603.

Wang, W., S. Alva, S. Wang, and A. Fort. 2011. Levels and trends in the use of maternal health services in developing countries. DHS Comparative Reports No. 26 . Calverton, Maryland, USA: ICF Macro. https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-cr26-comparative-reports.cfm

DHS-8 Tabulation plan: Table 9.1

API Indicator IDs:

RH_ANCP_W_DOC, RH_ANCP_W_NRS, RH_ANCP_W_AUX, RH_ANCP_W_CHW, RH_ANCP_W_OHW, RH_ANCP_W_TBA, RH_ANCP_W_OTH, RH_ANCP_W_MIS, RH_ANCP_W_NON, RH_ANCP_W_SKP

( API link , STATcompiler link )

MICS6 Indicator TM.5a: Antenatal care coverage: at least once by skilled health personnel.

Changes over Time

This indicator changed significantly in DHS-8. The reference time period for this indicator changed from 5 years to 2 years, reflecting a shorter time period asked about in the women’s questionnaire. Also, the population base for this indicator was expanded from only women who had at least one live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey to include women who had a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey, as well as women who had one or more births (either live birth or stillbirth) in the 2 years preceding the survey. Finally, the categories of providers changed slightly. “Auxiliary nurse/midwife” was changed to “Auxiliary midwife” and “Community health worker” was changed to “Community health worker/fieldworker”.

Percent distribution of number of antenatal care visits, and of timing of first antenatal visit

1) Percentage of women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years, distributed by number of antenatal care visits for most recent birth.

2) Percentage of women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years, distributed by number of months pregnant at time of first antenatal care visit for most recent birth.

1) Received antenatal care for their last most recent live birth (m80 = 1) and/or stillbirth (m80 = 3), according to grouped number of visits (m14)

2) Received antenatal care for their last most recent live birth (m80 = 1) and/or stillbirth (m80 = 3), according to grouped number of months they were pregnant at time of first visit (m13)

c) Women who have had a live birth or a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey (m80 = 1 or 3 & p19 < 24)

Number of antenatal visits is grouped into categories of no antenatal visits, 1 visit, 2 visits, 3 visits, 4-7 visits, 8+ visits, and “don’t know” before calculating percentages. Timing of first antenatal visit is grouped into categories of no antenatal visit, <4 months, 4-6 months, 7+ months, and “don’t know” before calculating percentages. The percentages are the numerators divided by the denominator, multiplied by 100.

"Don't know" or missing values on number of antenatal care visits and timing of first ANC are excluded from numerators but included in denominators.

Percent distributions add up to 100 percent.

In DHS-8, the reference time period for this indicator changed from 5 years to 2 years, reflecting a shorter time period asked about in the women’s questionnaire. The population base for this indicator was also expanded from only women who had at least one live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey to include women who had a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey, as well as women who had one or more births (either live birth or stillbirth) in the 2 years preceding the survey.

Also, in DHS-8, the groupings were changed to include 8+ ANC visits based on WHO recommendations.

Benova, L., Ö. Tunçalp, A.C. Moran and O.M.R. Campbell, 2018. “Not just a number: examining coverage and content of antenatal care in low-income and middle-income countries.” BMJ Global Health , 3 (2), p.e000779. https://gh.bmj.com/content/3/2/e000779

MacQuarrie, K.L.D., L. Mallick, and C. Allen. 2017. Sexual and reproductive health in early and later adolescence: DHS data on youth Age 10-19 . DHS Comparative Reports No. 45. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF. https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-cr45-comparative-reports.cfm

Owolabi, O.O., K.L.M. Wong, M.L. Dennis, E. Radovich, F.L. Cavallaro, C.A. Lynch, A. Fatusi, I. Sombie, and L. Benova. 2017. "Comparing the Use and Content of Antenatal Care in Adolescent and Older First-Time Mothers in 13 Countries of West Africa: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys." The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 1(3):203-212. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352464217300251

Wang, W., S. Alva, S. Wang, and A. Fort. 2011. Levels and trends in the use of maternal health services in developing countries . DHS Comparative Reports No. 26. Calverton, Maryland, USA: ICF Macro. https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-cr26-comparative-reports.cfm

World Health Organization. 2016. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience . Geneva: World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/anc-positive-pregnancy-experience/en/

World Health Organization. 2018. Global reference list of 100 core health indicators . Geneva: World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259951

DHS-8 Tabulation plan: Table 9.2

RH_ANCN_W_NON, RH_ANCN_W_N01, RH_ANCN_W_N23, RH_ANCN_W_N4P, RH_ANCN_W_DKM,

RH_ANCT_W_NON, RH_ANCT_W_TL4, RH_ANCT_W_T45, RH_ANCT_W_T67, RH_ANCT_W_T8P, RH_ANCT_W_DKM

WHO 100 Core Health Indicators: Antenatal care coverage

MICS6 Indicator TM.5b: Antenatal care coverage: at least four times by any provider.

MICS6 Indicator TM.5c: Antenatal care coverage: at least eight times by any provider

Median number of months pregnant at time of first antenatal care visit

Median number of months pregnant at the time of first antenatal care visit for the most recent birth (live birth or stillbirth) in the 2 years preceding the survey.

a) Women who have had alive birth in the 2 years preceding the survey (NR file)

Time period: Two years preceding the survey.

Number of women within each base population who received antenatal care for their most recent live birth (m80 = 1) or stillbirth (m80 = 3) according to the single number of months they were pregnant at time of first visit (m13)

a) Women who have had a live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey who received antenatal care for the live birth (m80 = 1 & m13 < 96 & p19 < 24)

b) Women who have had a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey who received antenatal care for the stillbirth (m80 = 3 & m13 < 96 & p19 < 24)

c) Women who have had a live birth or a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey who received antenatal care for their last birth (m80 = 1 or 3 & m13 < 96 & p19 < 24)

For the median, first calculate percentages of single months pregnant at first visit by dividing the numerators by the denominator. Cumulate the percentages by single months starting with the lowest value.

Linearly interpolate between the number of months immediately before and after where the cumulated distribution exceeds 50 percent to determine the median. See Median Calculations in Chapter 1 .

“Don’t know” and missing values excluded from numerators and denominator of percentages for median calculation.

In DHS-8, the reference time period for this indicator changed from 5 years to 2 years, reflecting a shorter time period asked about in the women’s questionnaire. Also, in DHS-8, the population base for this indicator was expanded from only women who had at least one live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey to include women who had a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey, as well as women who had one or more births (either live birth or stillbirth) in the 2 years preceding the survey.

DHS-8 Tabulation plan: Table 9.2

RH_ANCT_W_MED

Percentage of women receiving components of antenatal care

1) Among women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years, the percentage that had their blood pressure measured.

2) Among women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years, the percentage that had a urine sample taken.

3) Among women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years, the percentage that had a blood sample taken.

4) Among women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years, the percentage that had the baby’s heartbeat listened for.

5) Among women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years the percentage that were counseled about maternal diet.

6) Among women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years the percentage that were counseled about breastfeeding.

7) Among women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years, the percentage that were asked about vaginal bleeding.

b) Women who received antenatal care for their most recent live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey (NR file)

c) Women who have had a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey (NR file)

d) Women who received antenatal care for their most recent stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey (NR file)

e) Women who have had a live birth or a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey (NR file)

f) Women who received antenatal care for their most recent birth (live birth or stillbirth) in the 2 years preceding the survey (NR file)

Number of women within each base population who:

1) had their blood pressure measured (m42c = 1)

2) had a urine sample taken (m42d = 1)

3) had a blood sample taken (m42e = 1)

4) had baby’s heartbeat listened for (m42f = 1)

5) were counseled about maternal diet (m42g = 1)

6) were counseled about breastfeeding (m42h = 1)

7) were asked about vaginal bleeding (m42i = 1)

Denominators: Number of women in each of the population bases:

b) Women who have had a live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey who received antenatal care for their last birth (m80 = 1 & m2n = 0 & p19 < 24)

c) Women who have had a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey (m80 = 3 & p19 < 24)

d) Women who have had a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey who received antenatal care for their stillbirth (m80 = 3 & m2n = 0 & p19 < 24)

e) Women who have had a live birth or a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey (m80 = 1 or 3 & p19 < 24)

f) Women who have had a live birth or a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey who received antenatal care for their last birth (m80 = 1 or 3 & m2n = 0 & p19 < 24)

For percentages, the numerator divided by the denominator, multiplied by 100.

“Don’t know” and missing values on key components of antenatal care (e.g., urine sample taken) are excluded from numerators but included in denominators, assuming that they did not receive the antenatal care component.

In DHS-8, a number of changes were made to indicators on content of ANC. First, the reference time period for this indicator changed from 5 years to 2 years, reflecting a shorter time period asked about in the women’s questionnaire. Second, the population base for this indicator was expanded from only women who had at least one live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey to include women who had a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey, as well as women who had one or more births (either live birth or stillbirth) in the 2 years preceding the survey. Additionally, maternal report of receipt of these specific items of ANC are now reported among both number of women with a livebirth and/or stillbirth in the last 2 years AND number of women who attended ANC for their livebirth and/or stillbirth in the last 2 years.

Several additional key items for content of ANC were added as a proxy for quality of care. These included listening to the baby’s heartbeat and counseling on maternal diet and breastfeeding.

Indicators on iron-supplementation and deworming used to be included in the same table as these components but are now presented in a separate table.

DHS-8 Tabulation plan: Tables 9.3.1 and 9.3.2

RH_ANCC_W_IRN, RH_ANCC_W_PAR, RH_ANCS_W_BLP, RH_ANCS_W_URN, RH_ANCS_W_BLS

MICS6 Indicator TM.6: Content of antenatal care

Percentage of women receiving food/cash assistance, deworming, and iron-containing supplementation during pregnancy

1) Percentage of women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years who received food or cash assistance during their most recent pregnancy.

2) Percentage of women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years who took intestinal parasite drugs during their most recent pregnancy.

3) Percentage of women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years who took iron tablets or syrup during their most recent pregnancy.

1) received food or cash assistance during the pregnancy of the most recent live birth or stillbirth (m82 = 1)

2) took iron tablets or syrup during the pregnancy for the most recent live birth or stillbirth (m45 = 1)

3) took intestinal parasite drugs during the pregnancy for the most recent live birth or stillbirth (m60 = 1)

“Don’t know” and missing values on indicators of food/cash assistance, deworming, and iron-containing supplementation are excluded from numerators but included in denominators, assuming that they did not receive the intervention.

In DHS-8, the reference time period for this indicator changed from 5 years to 2 years, reflecting a shorter time period asked about in the women’s questionnaire. Also in DHS-8, the population base for this indicator was expanded from only women who had at least one live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey to include women who had a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey, as well as women who had one or more births (either live birth or stillbirth) in the 2 years preceding the survey.

The indicator on food/cash assistance was added in DHS-8. The indicators on iron-supplementation and deworming used to be included in the same table as the other ANC components but are now presented in a separate table.

Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Bahl R, et al. Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? Lancet 2014;384(9940):347–70

DHS-8 Tabulation plan: Table 9.4

Percent distribution of number of days taking iron-containing supplements during pregnancy

Percentage of women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years, distributed by number of days taking iron-containing supplements during their most recent pregnancy.

Number of women within each base population who by number of days she took iron-containing supplements during the most recent pregnancy (m46)

Number of days during which women took iron-containing supplements is grouped into categories of none, <60, 60-89, 90-179, 180+, and “don’t know” before calculating percentages. Percentages are the numerators divided by the denominator, multiplied by 100.

“Don’t know” values included in percent distributions. Missing values are excluded from numerators but included in denominators.

(API link TBD, STATcompiler link TBD)

Percentage of women who obtained iron-containing supplements, by source of supplements

Percentage of women with a live birth or a stillbirth in the last 2 years who obtained iron-containing supplements during their most recent pregnancy, by source of supplements.

a) Women who have had a live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey who were given or bought iron-containing supplements during the pregnancy of the most recent live birth (NR file)

b) Women who have had a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey who were given or bought iron-containing supplements during the pregnancy of the most recent stillbirth (NR file)

c) Women who have had a live birth or a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey who were given or bought iron-containing supplements during the most recent pregnancy (NR file)

Number of women within each base population who were given or bought iron-containing supplements during pregnancy, by declared source of iron-containing supplements (m45 = 1 & m81a – x)

a) Women who have had a live birth in the 2 years preceding the survey who were given or bought iron-containing supplements during the pregnancy of the most recent live birth (m80 = 1 & m45 =1 & p19 < 24)

b) Women who have had a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey who were given or bought iron-containing supplements during the pregnancy of the most recent stillbirth (m80 = 3 & m45 =1 & p19 < 24)

c) Women who have had a live birth or a stillbirth in the 2 years preceding the survey who were given or bought iron-containing supplements during the most recent pregnancy (m80 = 1 or 3 & m45 =1 & p19 < 24)

Numerators divided by the same denominator and multiplied by 100.

Supplements may have been obtained from more than one source.

DHS-8 Tabulation plan: Table 9.5

- Open access

- Published: 17 November 2021

Timing of first antenatal care visits and number of items of antenatal care contents received and associated factors in Ethiopia: multilevel mixed effects analysis

Zeitpunkt der ersten Besuche bei der Schwangerenvorsorge und Anzahl der erhaltenen Inhalte der Schwangerenvorsorge und damit verbundene Faktoren in Äthiopien: Mehrebenenanalyse mit gemischten Effekten

- Berhanu Teshome Woldeamanuel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1930-5432 1 &

- Tadesse Ayele Belachew 1

Reproductive Health volume 18 , Article number: 233 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

3162 Accesses

12 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Receiving quality antenatal care (ANC) from skilled providers is essential to ensure the critical health circumstances of a pregnant woman and her child . Thus, this study attempted to assess which risk factors are significantly associated with the timing of antenatal care and the number of items of antenatal care content received from skilled providers in recent pregnancies among mothers in Ethiopia.

The data was extracted from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2016. A total of 6645 mothers were included in the analysis. Multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression analysis and multilevel mixed Negative binomial models were fitted to find the factors associated with the timing and items of the content of ANC services. The 95% Confidence Interval of Odds Ratio/Incidence Rate Ratio, excluding one, was reported as significant.

About 20% of the mothers initiated ANC within the first trimester, and only 53% received at least four items of antenatal care content. Being rural residents (IRR = 0.82; 95%CI: 0.75–0.90), wanting no more children (IRR = 0.87; 95%CI: 0.79–0.96), and the husband being the sole decision maker of health care (IRR = 0.88; 95%CI: 0.81–0.96), were associated with reduced items of ANC content received. Further, birth order of six or more (IRR = 0.74; 95%CI: 0.56–0.96), rural residence (IRR = 0.0.41; 95%CI: 0.34–0.51), and wanting no more children (IRR = 0.61; 95%CI: 0.48–0.77) were associated with delayed antenatal care utilization.

Conclusions

Rural residences, the poorest household wealth status, no education level of mothers or partners, unexposed to mass media, unwanted pregnancy, mothers without decision-making power, and considerable distance to the nearest health facility have a significant impact on delaying the timing of ANC visits and reducing the number of items of ANC received in Ethiopia. Mothers should start an antenatal care visit early to ensure that a mother receives all of the necessary components of ANC treatment during her pregnancy.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund.

Eine qualitativ hochwertige Schwangerenvorsorge (ANC) durch qualifizierte Anbieter ist für die Sicherung der kritischen Gesundheitslage einer schwangeren Frau und ihres Kindes unerlässlich. In dieser Studie wurde daher untersucht, welche Risikofaktoren bei Müttern in Äthiopien in signifikantem Zusammenhang mit dem Zeitpunkt der Schwangerenvorsorge und der Anzahl der Inhalte der Schwangerenvorsorge stehen, die in den letzten Schwangerschaften von qualifizierten Anbietern durchgeführt wurden.

Die Daten wurden aus dem Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2016 extrahiert. Insgesamt wurden 6645 Mütter in die Analyse einbezogen. Es wurden mehrstufige logistische Regressionsanalysen mit gemischten Effekten und mehrstufige gemischte negative Binomialmodelle verwendet, um die Faktoren zu ermitteln, die mit dem Zeitpunkt und den Inhalten der ANC-Leistungen in Verbindung stehen. Das 95%ige Konfidenzintervall der Odds Ratio/Inzidenzrate, mit Ausnahme von einem, wurde als signifikant angegeben.

Etwa 20% der Mütter begannen die ANC innerhalb des ersten Trimesters, und nur 53% erhielten mindestens vier Elemente der Schwangerenvorsorge. Die Tatsache, dass die Mütter auf dem Land wohnten (IRR = 0,82; 95%CI: 0,75–0,90), keine weiteren Kinder wollten (IRR = 0,87; 95%CI: 0,79–0,96) und der Ehemann der alleinige Entscheidungsträger für die Gesundheitsfürsorge war (IRR = 0,88; 95%CI: 0,81–0,96), war mit einer geringeren Anzahl an erhaltenen ANC-Inhalten verbunden. Außerdem waren die Reihenfolge der Geburten von sechs oder mehr (IRR = 0,74; 95%CI: 0,56–0,96), der Wohnsitz auf dem Land (IRR = 0,0,41; 95%CI: 0,34–0,51) und der Wunsch, keine weiteren Kinder zu bekommen (IRR = 0,61; 95%CI: 0,48–0,77) mit einer verzögerten Inanspruchnahme der Schwangerenvorsorge verbunden.

Schlussfolgerungen

Ländliche Wohnorte, der geringste Wohlstand des Haushalts, kein Bildungsniveau der Mütter oder Partner, keine Exposition gegenüber Massenmedien, ungewollte Schwangerschaft, Mütter ohne Entscheidungsbefugnis und eine große Entfernung zur nächsten Gesundheitseinrichtung haben in Äthiopien einen signifikanten Einfluss auf die Verzögerung von ANC-Besuchen und die Verringerung der Anzahl der erhaltenen ANC-Posten. Die Mütter sollten frühzeitig mit der Schwangerenvorsorge beginnen, um sicherzustellen, dass sie während ihrer Schwangerschaft alle notwendigen Bestandteile der ANC-Behandlung erhalten.

Plain language summary

The third Sustainable Development Goals prioritizes maternal mortality reduction, intending to lower the worldwide maternal mortality rate to 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030. Regular antenatal care from a skilled provider reduces maternal mortality by 20%. The overall quality of ANC service is determined collectively by the timing of ANC, and the contents of ANC received. Though there is an increase in ANC visits and the quality of services received, only 74% of women who gave birth in 2019 received antenatal care from a skilled provider, ranging from 85% in the urban to 70% in the rural. Thus, the quality and content of care might remain poor while the coverage of ANC visits is high. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the levels and risk factors that affect the timing of ANC visits and contents to assess the quality of ANC services. This is the focus of the current study's research. In this study, nationally representative data from the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey was employed. Our study shows that rural residences, the poorest wealth quintile, no education level, unexposed to mass media, unwanted pregnancy, without decision-making power, and being far from the nearest health facility were found to be factors that hinder early initiation of ANC visits and reduce the number of items of ANC received. In conclusion, we ought to initiate an ANC visit early for a frequent antenatal care visit so that a mother will receive the necessary ANC components.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Maternal mortality reduction and enhancements in women’s health care are priorities of the third Sustainable Development Goal (SDGs) aimed to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio (MMR) to 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030 [ 1 ]. Between 2000 and 2017, the global maternal mortality rate (MMR) was reduced by 38% [ 2 ]. In Ethiopia, despite a 71.8% decline in MMR between 1990 and 2015, 1 in 64 women are at risk of dying from maternal-related causes, which is a big gap compared with MMR of 199 per 100, 000 live births plan 2020 [ 3 ]. It shows that more effort is needed to achieve the SGDs after ten years. Regular antenatal care from a skilled provider reduces maternal mortality by 20% [ 4 , 5 ]. According to the 2019 Ethiopian mini Demographic and Health Survey, 74% of women who gave birth in the five years before the survey received antenatal care (ANC) from a skilled provider, ranging from 85% in urban areas to 70% in rural areas [ 6 ]. Further, Ethiopia’s DHS 2016 revealed 75% of pregnant women had their blood pressure measured, 73% had a blood sample taken, 66% had a urine sample taken, and 66% received nutritional counseling during their ANC visits [ 7 ].

The use of health facilities is significantly associated with ANC visits, and sufficient ANC involves both the use of services and the sufficiency of the content within the services [ 8 , 9 ]. The 2016 Ethiopia DHS reports that only 20% of women had their first ANC visits in the first trimester, which calls for more ANC attendance [ 7 ]. Furthermore, concerning the type of skilled provider, doctors (5.7%), nurses/midwives (42%), health officers (1.4%), and health extension workers (13.2%) received ANC service.

Previous studies regarding antenatal care in Ethiopia and elsewhere recognized that women’s autonomy [ 10 , 11 , 12 ], birth order and the number of children born [ 13 , 14 , 15 ], husband’s attitude and support [ 10 , 16 ], lack of money [ 17 ] were the main reasons for lower health care utilization. Some studies reported that the education level of mother or husband/partner [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 15 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ], age [ 10 , 11 , 14 , 19 ], woman’s occupation [ 10 , 17 ], place of residence [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 20 ], place of receiving [ 15 , 19 ], access to mass media [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 15 , 17 , 18 ], wealth quintile [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 18 , 19 ], and ANC provider [ 15 ] were the most important factors that affected the utilization of antenatal care services. According to the literature, wanted pregnancy [ 12 , 15 , 17 , 19 , 20 ], a lack of health care services such as a long distance to the health facility [ 10 , 17 , 19 ], health insurance [ 10 ], and permission to visit a health facility [ 17 ] were significant factors associated with antenatal care utilization and service quality.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the first visit received before 12 weeks of pregnancy and the necessary contents of ANC visits to improve women’s care experience and reduce perinatal mortality [ 21 ]. Even though there is an increase in ANC visits and the quality of services received, many women are still not timely initiating the first ANC visit in Ethiopia. As a result, they have not received the critical contents of ANC. Though several studies in the past year in Ethiopia have explicitly examined associated factors of antenatal care utilization and completion of four or more visits during pregnancy [ 11 , 14 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ], these studies did not investigate the actual number of components of ANC service a woman has received. Besides, these studies revealed that the contents of ANC visit highly influence the effectiveness of the ANC service. Thus, the quality and content of care might remain poor while the coverage of ANC visits is high. The overall quality of ANC service is determined collectively by the timing of ANC, and the contents of ANC received. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the levels and risk factors that affect the timing of ANC visits and contents to assess the quality of ANC services. This is the focus of the current study's research.

Study setting, data and population

We used population based, nationally representative data from 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) [ 7 ]. The survey was conducted by the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) in collaboration with the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) and the Ethiopian Public Health Institute with technical assistance from ICF International and financial support from USAID, the government of the Netherlands, the World Bank, Irish Aid, and UNFPA from January 18, 2016, to June 27, 2016. The 2007 Ethiopia Population and Housing Census sampling frame with 84,915 enumeration areas (EAs), each EAs covering 181 households, was used. The respondents were selected using a stratified two-stage cluster design, each region stratified into urban and rural areas.

First was selecting 645 clusters (202 urban areas and 443 rural areas) with probability proportional to enumeration area size and independent selection within each stratum. In all the selected EAs, the household listing was done from September to December 2015. At the second stage, 28 households were selected per cluster with an equal probability systematic selection involving eligible women aged 15–49 years. Thus, a sample of 16,650 households and 15,683 women aged 15–49 years was identified with a response rate of 94.6%. Furthermore, details of the survey design and methodology have been reported in the 2016 EDHS [ 7 ].

Our analysis was based on the records of 6645 (54.3%) women who have complete information on the number of ANC visits, the timing of their first ANC visits, the contents of their ANC visits, and who gave birth in the five years preceding the survey. The latest deliveries were referred to all women.

This study has two response variables: Timing of first ANC visits; binary outcome categorized into 1 if a mother starts her first ANC visits within the first trimester (early initiation, or 12 weeks after the onset of pregnancy) and 0 elsewhere. Second, the contents of ANC received during pregnancy (a discrete outcome measured as the number of items WHO recommended and recognized as the contents of ANC) in Ethiopia received by a mother during pregnancy.

Standard guidelines for ANC in Ethiopia recognize that every pregnant woman should receive ANC from a skilled provider that consists of iron supplements, intestinal parasite drugs, at least two doses of Tetanus Toxoid injections, malaria intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy, and health education on danger signs and complications during pregnancy; blood pressure measurement; urine tests; blood tests; health education on prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV/AIDS and HIV/AIDS counseling, testing, and collection of results. The composite index comprises a simple count of items received from skilled providers during the ANC visits. The variable had a minimum value of zero, indicating that the mother had not taken any items or received ANC. A maximum value of ten indicates that she has received all the nationally recommended and recognized content of the ANC. The important explanatory variables explored from previously available literature [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ] are presented in Table 1 .

The wealth index was coded as: 1 = poorest, 2 = poorer, 3 = middle, 4 = richer, and 5 = richest. The wealth quintile of women’s households in EDHS is a composite indicator that scores were derived using principal component analysis based on housing characteristics and ownership of household durable goods [ 7 ]. National wealth quintiles are compiled by assigning the household score to each usual (de jure) household member, ranking each person in the household population by their score, and dividing the distribution into five equal categories, each comprising 20% of the population.

In EDHS 2016, birth order is a discrete variable ranging from 1 to 20. The proportion of birth orders two versus three and four versus five is nearly equal, so birth orders two and three and four and five were merged for this analysis. Further, the proportion of children with higher birth orders is relatively small, and birth orders of six and higher have been merged since the percentage distribution. The same categories were also used in the earlier study by Muchie [ 14 ]. Similarly, the percentage of women working in professional, technical, managerial, clerical, or unskilled manuals after screening for missing variables is too small, and the authors merge these two categories for this analysis. These too-few frequencies may, in turn, affect the parameter estimation.

Statistical methods of data analysis

Data analysis was done using the “R programming” version 4.0.3. Descriptive statistics of the subjects were summarized using frequency tables. A Chi-square test was performed to observe any association between the timing of the first ANC visit and the independent variables. An F-test based on analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the mean difference in the numbers of components of ANC received. Furthermore, the multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression was fitted to identify variables associated with the timing of first ANC visits. Meanwhile, multilevel mixed-effects count models were performed to identify factors associated with the number of ANC components received from a skilled provider during pregnancy.

First, a Poisson regression model with a log link was performed [ 22 ]. Then fitted Poisson regression checked for the problem of overdispersion (variance can be larger than the mean) or under dispersion (variance can be smaller than the mean) using the likelihood test. It was found that this test was significant. Therefore, the negative binomial (NB) regression model was considered the immediate solution for data analysis [ 23 ]. Moreover, the data experiencing excess zeros and overdispersion might be due to these excess zeros. Thus, we performed both the zero-inflated models (Zero Inflated Poisson and Zero Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB)) and the Hurdle models (Hurdle Poisson (HP) and Hurdle Negative Binomial (HNB)) to check if overdispersion is accounted for due to excess zeros [ 24 ].

To account for the correlation between measurements (intra-cluster correlation (ICC)), we used the multilevel mixed-effects models (cluster/region-specific random effects). The use of a multilevel modeling approach accounts for the hierarchical nature of the EDHS data, where households were selected within EA clusters. There could be unobserved characteristics of cluster influencing women’s decision to timely initiate ANC and the number of ANC visits, such as the availability and accessibility of health services, cultural norms, and prevailing health beliefs. The outcomes of households within the same cluster are likely to correlate. Ignoring this correlation can underestimate variability (producing biased standard errors) and present falsely narrow confidence intervals [ 25 , 26 , 27 ].

Further, disregarding the hierarchical structure of the data and analyzing it as single-level data leads to incorrect inferences (i.e., high type I errors or loss of power) [ 28 ]. Finally, based on the Vuong statistic [ 29 ], likelihood ratio test, the Deviance, AIC, and BIC for model comparison, the multilevel mixed-effects negative binomial model best-fit factors associated with the number of items of ANC received from a skilled provider (see Additional file 1 ). Variables with a 95% confidence interval for the incidence risk ratio (IRR) excluding one were considered statistically significant determinants.

Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of respondents

This study included 6645 women who had given birth within the five years preceding the survey. The background characteristics of women with respect to the timing of ANC visits are given in Table 2 . Most women (70.3%) were from rural areas, while only 29.7% were from urban areas. Concerning regions, a slightly higher percentage were from Tigray (14.6%), SNNPR (13.3%), Oromia (11.2%), and Amhara (10.7%), while the smallest percent of women were from Afar (6.1%), Gambela (6.8%), and Harari (6.8%). The median age was 27 years. Around 32% were from the richest, and 23% were from the poorest wealth quintile. The majority (49.5%) of women had no education, 32.8% had primary education, and only 6.6% had a higher education level. Regarding media access, only 2.8%, 16.3%, and 21.2% have read a newspaper or magazine, listened to the radio, and watched television at least once a week during their recent pregnancy.

On the other hand, concerning decision-making power over women’s health care, about two-thirds (65%) reported that both women and husbands/partners usually decide on respondents’ health care. Further, about 26% said they had a big problem getting permission to seek medical care, 50.1% had a big problem getting money for treatment in seeking medical care, and 44.2% had a far distance to a health facility in seeking medical care. In comparison, 33.7% reported a big problem in not wanting to go alone to seek medical care. In addition, the majority (80%) of women reported that their last child was wanted at the time of pregnancy. In comparison, 14.7% said the pregnancy was wanted later, and 5.3% reported they wanted no more.

Timing of first ANC visit by some characteristics of women

Only 20.1% of women started their ANC visit within the first trimester, with a median of four months for the first ANC visit. The proportion starting first ANC within the first trimester was lower in the SNNPR (22.2%), Benishangul-gumuz (23.1%), and Somali regions (32.1%), whereas it was higher in Dire Dawa (68.6%) and Addis Ababa (62.5%) cities. More than half (56.2%) of women from urban areas started their first ANC visit within the first trimester compared to 31.1% of rural women. Women who had higher levels of education (63.6%) and primary education (40%) started first ANC within the first trimester compared to uneducated women (31%). Further, women whose husbands/partners had higher education had the highest proportion (57%) of their first ANC visit within the first trimester.

The time to early initiate the first ANC visit was almost uniform among women’s age and occupation. The majority of women who read newspapers or magazines at least once a week (52%), who listen to the radio at least once a week (46%), and who watch television at least once a week (58%) started their ANC visits for their recent pregnancy within the first trimester. On the other hand, the proportion of women who began their first ANC visit within the first trimester increases with women’s autonomy concerning decisions about health care. Most women whose pregnancy was wanted (40%) started their first ANC visit within the first trimester and wanted no more children (25%). Moreover, 43% of women who had no problem getting money, 42.3% of women with a short distance to the nearest health facility, and 41% who had no difficulty going alone in seeking medical care had started their first ANC visit within the first trimester.

The number of items of ANC content received by some characteristics of mothers

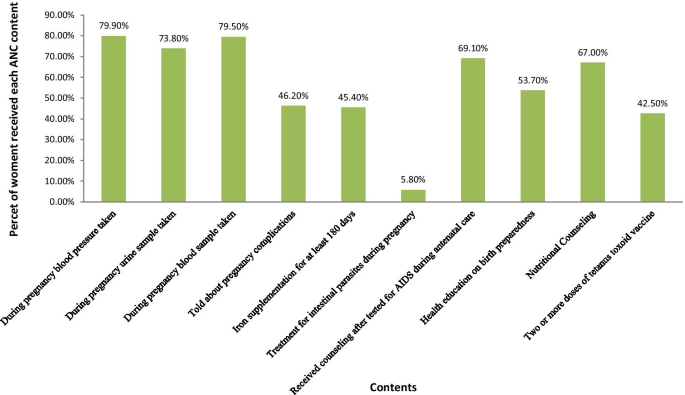

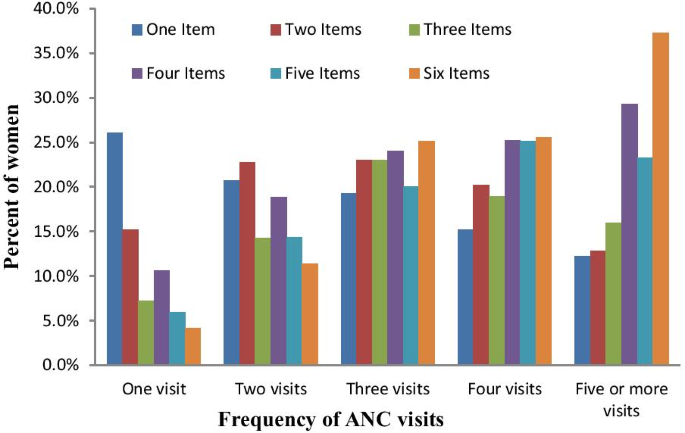

Of all women who received ANC at least once, 79.9% had their blood pressure measured, 73.8% had a urine sample taken, and 79.5% had a blood sample taken. Further, 46.3% had been told about pregnancy complications, 45.4% received iron supplementation for at least 180 days, and 5.8% of women received treatment for an intestinal parasite. Additionally, 69.1% received counseling after testing AIDS, 53.7% were informed about birth preparedness, 67% received nutritional counseling, and 42.5% received two or more doses of tetanus toxoid vaccine from a skilled provider during their ANC visits (Fig. 1 ). The mean number of ANC contents received by a woman was 3.5 items and a standard deviation of 2.2, indicating that the distribution is overdispersed. Figure 2 presents a further detailed examination of the relationship between the frequency of ANC visits and the number of items of ANC contents received. It revealed that the likelihood of receiving the highest number of items of ANC content increases with the frequency of ANC visits. The proportion of women who received six items has monotonically increased from 4.2 to 37.3%, increasing ANC visits from one visit to at least five ANC visits (Fig. 2 ).

Types of items of ANC Contents received during pregnancy in Ethiopia, EDHS 2016, n = 6645

Percentage distribution of number of items of ANC contents received by frequency of ANC visits in Ethiopia, EDHS 2016

Conversely, the pattern showed a declining trend of the likelihood of receiving only one item or two items, or three items, with an increase in the number of ANC visits. In addition, the timing of the first ANC visit showed a positive association with the mean number of items of ANC contents received. For instance, a woman who started her first ANC visit within the first trimester received, on average, 6.2 items. In comparison, women who had received only one ANC visit had received an average of 3.8 items, compared to virtually six items on average among women with four or more ANC visits (Table 3 ).

Factors associated with the timing of the first ANC visits: multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression analysis

The multivariable multilevel logistic regression analysis of factors associated with the timing of the first ANC visit is given in Table 4 . The likelihood of timely initiating the first ANC visit was lower among six or more birth orders (AOR = 0.74; 95%CI: 0.56–0.96) than the first birth order. Moreover, rural women were 59% less likely to start their first ANC visit within the first trimester (AOR = 0.41; 95%CI: 0.31–0.54) than urban counterparts.

The log odds of timely initiating the first ANC visit were higher among the richest wealth quintile (AOR = 2.17; 95%CI: 1.61–2.92), the 4 th (AOR = 2.29; 95%CI: 1.87–2.81), and the 3 rd (AOR = 2.02; 95%CI: 1.68–2.42) wealth quintile, respectively, as compared to the poorest wealth quintile. The odds of starting the first ANC visit within the first trimester was 5.2 times (AOR = 5.20; 95%CI: 2.25–12.03), 2.14 times (AOR = 2.14; 95%CI: 1.50–3.06) and 1.73 times (AOR = 1.73; 95%CI: 148–2.02), higher among women with a higher, secondary and primary level of education, respectively, as compared to uneducated women after controlling for other variables in the model. Similarly, women whose husbands had higher education levels were 45% (AOR = 1.45; 95%CI: 1.08–1.95) more likely to start their ANC within the first trimester than those whose husbands had not been educated. Women aged 40–44 years old were 34% (AOR = 0.66; 95%CI: 0.44–0.99) less likely to start their first ANC visit on time than women aged 15–19 years old.

Furthermore, women who listened to the radio less than once a week (AOR = 1.56; 95%CI: 1.25–1.93), at least once a week (AOR = 1.49; 95%CI: 1.20–1.85) and watched television at least once a week (AOR = 1.58; 95%CI: 1.11–2.23), respectively, were more likely than those who did not listen to the radio or watch television to start their first ANC in the first trimester. Pregnant women who want no more children were 39% (AOR = 0.61; 95%CI: 0.48–0.77) less likely to start their first ANC visit within the first trimester than those whose pregnancies were wanted. Furthermore, a woman who reported a short distance to a health facility seeking medical care was 55% (AOR = 1.55; 95%CI: 1.35–1.78) more likely to start her first ANC visit within the first trimester (Table 4 ).

Factors associated with the number of ANC content items received by a woman: Multilevel mixed-effects Negative binomial analysis

The estimated incidence rate ratio (IRR) indicates that women from rural areas (IRR = 0.82; 95%CI: 0.75–0.90) and female heads (IRR = 0.91; 95%CI: 0.85–0.97) were significantly associated with lower numbers of items of ANC content received. Further, women who wanted no more children (IRR = 0.87; 95%CI: 0.79–0.96), whose husbands/partners decided alone, were significantly associated with lower numbers of items of ANC content received. In contrast, women from the richest wealth quintile (IRR = 1.51; 95%CI: 1.36–1.67), 4 th wealth quintile (IRR = 1.62; 95%CI: 1.49–1.75) and 3 rd wealth quintile (IRR = 1.47; 95%CI: 1.37–1.59), women who had primary education (IRR = 1.24; 95%CI: 1.17–1.32), secondary education (IRR: 1.22, CI: 1.10–1.34) and higher education (IRR = 1.21; 95%CI: 1.05–1.39) as well as women whose partners had primary education (IRR = 1.17; 95%CI: 1.01–1.24), secondary education (IRR = 1.21; 95%CI: 1.11–1.34) and higher education (IRR = 1.16; 95%CI: 1.04–1.30) were more likely to receive a higher number of items of ANC contents. Additionally, women who have no problem of getting permission (IRR = 1.10; 95%CI: 1.03–1.17), who reported short distance to health facilities (IRR = 1.19; 95%CI: 1.12–1.26), who listen to the radio less than once a week (IRR = 1.12; 95%CI: 1.04–1.19) and at least once a week (IRR = 1.15; 95%CI: 1.07–1.23), who watch television less than once a week (IRR = 1.09; 95%CI: 1.01–1.19), who had received 1–3 ANC (IRR = 5.12; 95%CI: 4.68–5.59) and at least four ANC (IRR = 6.08; 95%CI: 5.56–6.65) from a skilled provider were significantly more likely to have a higher number of items of ANC contents during their pregnancy.

The study found that 53% of women received at least four ANC items, while 20% started their first ANC visit within the first trimester. The multilevel negative binomial regression analysis revealed that the covariates of rural residents and an unwanted child at the time of pregnancy were significantly associated with the lower incidence rate ratio of the number of ANC contents received. Further, the frequency of ANC visits during pregnancy was significantly associated with a higher incidence rate ratio of ANC contents received. In contrast, female heads were significantly associated with a lower incidence rate ratio of ANC contents received. The multilevel logistic regression analysis revealed that having six or more birth orders, living in a rural area, being between the ages of 40 and 44, and wanting no more children were all significantly associated with a lower likelihood of initiating ANC visits on time. Higher wealth quintile, higher education level of women and partners, access to mass media, and a short distance to the health facility in seeking medical care, on the other hand, were significantly associated with increased odds of initiating an ANC visit for a recent pregnancy within the last five years before the survey.

This study showed that higher birth order was inversely associated with the timing of the ANC visit, i.e., women were less likely to start their ANC visit within the first trimester of their sixth or higher birth order. A similar study in Uganda [ 30 ] found mothers with third birth orders, compared to those with the first, are about 6–7% less likely to attain the four antenatal visits, and mothers with at least the third birth order are 4–5% less likely to initiate the first visit in the first trimester. Muchie [ 14 ], using Ethiopian Mini DHS 2014, also found 38 and 36% lower odds of completing four or more visits of ANC utilization for birth orders of children four or five, and six or more, respectively. One possible reason for this might be mainly in the first pregnancy when women wanted lots of contact with their care provider. Some women would have liked more communication between appointments and were worried about having to deal with pregnancy complications and pain.

Rural mothers are less likely to receive higher ANC content from skilled providers and start ANC visits within the first trimester than urban mothers. This finding is congruent with that of Beeckman et al. [ 10 ], who reported higher odds of delaying first ANC visits and ANC visits of less than four among rural mothers. Further, a study done in Bangladesh, [ 12 ] found rural mothers are 17% less likely to attend a higher number of ANC visits than urban mothers. Another similar finding from Bangladesh [ 8 ] reported that urban mothers were 1.35 times more likely to receive more items of ANC services from a skilled provider than their rural counterparts. In Ethiopia’s rural areas, there is a lack of skilled health care providers, lack of information on antenatal care services, lack of infrastructure, and long distances from health facilities.

Moreover, most mothers in rural Ethiopia were uneducated. Contrary to our findings, Gebremeskel et al. [ 31 ] and Weldearegawi et al. [ 32 ] reported residence was not associated with the timing of the first ANC visit. This inconsistency might be due to the statistical methodology used and the smaller sample size used by Gebremeskel et al. [ 31 ] (n = 409) and Weldearegawi et al. [ 32 ] ( n = 402), whereas the EDHS 2016 used (n = 6645).

Furthermore, we found that women with at least primary education levels are more likely to start the first ANC visit within the first trimester and receive the highest number of items of ANC content from skilled providers. Similarly, women whose partners had at least a primary education were more likely to receive higher ANC content from skilled providers than the uneducated category. Additionally, women whose partners had higher education were more likely to start ANC visits within the first trimester than those without. Further analysis of the 2011 Ethiopian DHS showed that women who had primary education (79%), secondary education (62%), and higher education were 45% times less likely to delay their first ANC visit [ 10 ]. Consistent with our finding, Islam [ 8 ] also found that there is a 1.12, 1.26, and 1.39 incidence rate ratio of receiving higher numbers of ANC content among women having primary, secondary, and higher education in Bangladesh. But, partners’ primary education level has not significantly increased the incidence of receiving the items of ANC content. In contrast, partners having a secondary or higher education significantly increased the incidence of receiving the items of ANC content [ 8 ].

In contrast, in Ghana, Manyeh et al. [ 33 ] found no significant effect of husband/partner education level on the timing of ANC visits. Additionally, a systematic review analysis in sub-Saharan Arica found that husband education was significantly associated with uptake, frequency, and timing of first ANC visits [ 10 ]. Most likely, this could be because educated women have more access to information and make their own decisions on their health care, which empowered them to exercise, and changed traditional attitudes about using the ANC service. This study suggests that there is an urgent need to focus on mothers’ education. Advocating primary education for girls and encouraging them to pursue secondary or higher education is essential to achieve a tangible change to achieve the sustainable development goals of maternal and infant mortality reduction through effective implementation of maternal health care services [ 14 , 34 ].

The result also suggests women who listened to the radio and watched television at least once a week were more likely to start their first ANC early and received more items of ANC content from skilled providers. This result agrees with the findings of Yaya et al. [ 11 ], where women who watch television at least once a week were 40% less likely to delay their first ANC visit than those who do not watch television at all. But they did not find an association between listening to the radio and the timing of the first antenatal care visit. This variation might be due to a difference in the methodology used. In Bangladesh [ 8 , 12 ], mass media access was associated with increased ANC content received.

Women whose pregnancies were unwanted or wanted later were more likely to delay their first ANC visit and less likely to receive the highest number of ANC content items than wanted pregnancies. A similar study of the Bangladeshi DHS found that wanted pregnancy was associated with a higher incidence of receiving higher items of ANC contents [ 8 ]. Another study from Bangladesh [ 12 ], Southern Ethiopia [ 31 ], Bahir Dar [ 35 ], and Eastern Tigray [ 32 ] found unwanted pregnancy significantly associated with delayed initiation of ANC service utilization. This might be that mothers with unwanted pregnancies have anxiety and poor psychological well-being [ 36 ] and less attention to pregnancy-related complications, and do not use supplements such as folic acid, vaccinations, health information, and nutritional counseling [ 37 ]. Thus, women ought to be encouraged to use modern contraceptives to prevent unwanted pregnancies.

Furthermore, women’s health decision-making power is significantly associated with the content of ANC services received. Women without decision-making power or whose husband/partner alone decides on their health care are strongly associated with lower ANC contents received. This result was congruent with those of northwest Ethiopia [ 38 ], Bangladesh [ 12 ], the systematic review of sub-Saharan Africa [ 10 ], and Tanzania [ 39 ]. However, unlike our findings, Gebresilassie et al. [ 40 ] found that decision-making on self-care seeking was not significantly associated with the timing of the first ANC visit.

Mothers with a shorter distance to the nearest health facility had better odds of initiating their first ANC visit and receiving items of ANC content from skilled providers. Similar findings are reported in a study in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia [ 35 ]. In the Eastern Tigray zone in Northern Ethiopia, distance to the nearest health facility was not a significant predictor of late antenatal care follow-up [ 32 ] . In Rwanda, distance to the health facility was not a significant predictor of poor quality of antenatal utilization [ 41 ]. Likewise, mothers who had permission to seek medical care were more likely to receive more ANC content.

Lastly, the results indicated that the frequency of ANC visits and timing of the first ANC visit during pregnancy was positively associated with the number of items of ANC contents a woman received from a skilled provider. Women who started antenatal care within the first trimester were more likely to receive more ANC contents items than those who delayed their visit. Likewise, the number of items of ANC content monotonically increases with frequent ANC visits. The findings are consistent with those of [ 42 , 43 ].

Findings of this study suggest that rural residences, the poorest wealth quintile, no education level of mothers or partners, unexposed to mass media, unwanted pregnancy, mothers without decision-making power, and a long distance to the nearest health facility have significant impacts on delaying the timing of ANC visits and reducing the number of items of ANC received in Ethiopia. Further, timely initiation of the ANC and the number of ANC visits were significantly associated with the increase in the number of items ANC received during pregnancy. Therefore, this study recommends that women initiate ANC visits timely and frequent antenatal care visits during pregnancy for the quality of ANC received from a skilled provider. Another implication of this study is that educating and empowering girls, particularly in the rural areas, are vital ingredients in all policies aiming to reduce maternal and neonatal deaths through improved quality of antenatal care utilization, particularly in the rural areas. Furthermore, encouraging women to use modern contraceptives, expanding health education in the media, and expanding health facilities are vital inputs that should be included in policies to improve the quality of antennal care utilization, particularly in rural areas. Moreover, women at low economic levels should be given special emphasis.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Antenatal care

Confidence interval

Central Statistics Agency

Demographic and Health Survey

Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey

Enumeration areas

Federal Ministry of Health

Hurdle Poisson

Hurdle negative binomial

Incidence rate ratio

Likelihood ratio test

Maternal Mortality Ratio

Negative Binomial

Sustainable Development Goals

United Nations Population Fund

United States Agency for International Development

World Health Organization

Zero Inflated Poisson

Zero Inflated Negative Binomial

United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations; 2015. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/.pdf