- What Was The Grand Tour...

What Was the Grand Tour and Where Did People Go?

Freelance Travel and Music Writer

Nowadays, it’s so easy to pack a bag and hop on a flight or interrail across Europe’s railway at your own leisure. But what if it was known as a right of passage, made no easier by the fact that there was no such modern luxury? Welcome to the Grand Tour – and we’re not talking about Jeremy Clarkson’s TV series …

What was the grand tour all about.

The Grand Tour was a trip of Europe, typically undertaken by young men, which begun in the 17th century and went through to the mid-19th. Women over the age of 21 would occasionally partake, providing they were accompanied by a chaperone from their family. The Grand Tour was seen as an educational trip across Europe, usually starting in Dover, and would see young, wealthy travellers search for arts and culture. Though travelling was not as easy back then, mostly thanks to no rail routes like today, those on The Grand Tour would often have a healthy supply of funds in order to enjoy themselves freely.

What did travellers get up to?

Of course, in the 17th century, there was no such thing as the internet, making discovering things while sat on the other side of the world near impossible. Cultural integration was not yet fully-fledged and nothing like we experience today, so the only way to understand different ways of life was to experience them yourself. Hence why so many people set off for the Grand Tour – the ultimate trip across Europe!

Typical routes taken on the Grand Tour

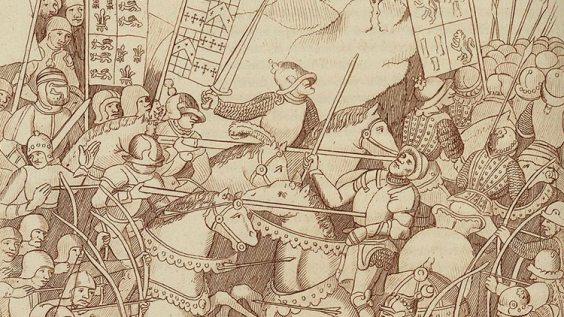

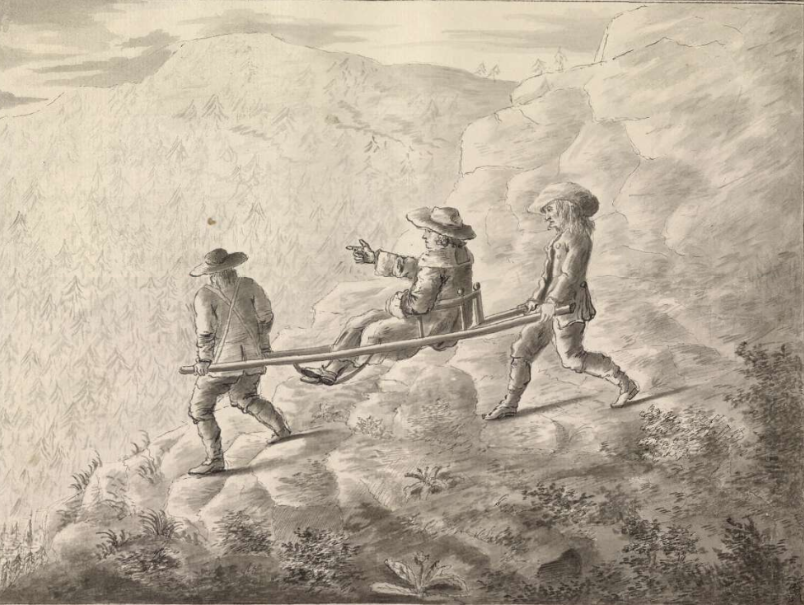

Travellers (occompanied by a tutor) would often start around the South East region and head in to France, where a coach would often be rented should the party be wealthy enough. Occasionally, the coaches would need to be disassembled in order to cross difficult terrain such as the Alps.

Once passing through Calais and Paris, a typical journey would include a stop-off in Switzerland before crossing the Alps in to Northern Italy. Here’s where the wealth really comes in to play – as luggage and methods of transport would need to be dismantled and carried manually – as really rich travellers would often employ servants to carry everything for them.

Of course, Italy is a highly cultural country and famous for its art and historic buildings, so travellers would spend longer here. Turin, Florence, Rome, Pompeii and Venice would be amongst the cities visited, generally enticing those in to extended stays.

On the return leg, travellers would visit Germany and occasionally Austria, including study time at universities such as Munich, before heading to Holland and Flanders, ahead of crossing the Channel back to Dover.

Since you are here, we would like to share our vision for the future of travel - and the direction Culture Trip is moving in.

Culture Trip launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful — and this is still in our DNA today. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes certain places and communities so special.

Increasingly we believe the world needs more meaningful, real-life connections between curious travellers keen to explore the world in a more responsible way. That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Culture Trips, Rail Trips and Private Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.

Culture Trips are deeply immersive 5 to 16 days itineraries, that combine authentic local experiences, exciting activities and 4-5* accommodation to look forward to at the end of each day. Our Rail Trips are our most planet-friendly itineraries that invite you to take the scenic route, relax whilst getting under the skin of a destination. Our Private Trips are fully tailored itineraries, curated by our Travel Experts specifically for you, your friends or your family.

We know that many of you worry about the environmental impact of travel and are looking for ways of expanding horizons in ways that do minimal harm - and may even bring benefits. We are committed to go as far as possible in curating our trips with care for the planet. That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.

Guides & Tips

The best private trips to book in europe.

The Best European Trips for Foodies

The Best Private Trips to Book With Your Support Group

The Best Rail Trips to Take in Europe

The Best Private Trips to Book for Your Religious Studies Class

The Best Places to Travel in May 2024

Places to Stay

The best private trips to book for your classical studies class.

The Best Places to Travel in August 2024

The Best Places in Europe to Visit in 2024

The Best Trips for Sampling Amazing Mediterranean Food

Five Places That Look Even More Beautiful Covered in Snow

The Best Private Trips to Book in Southern Europe

Culture trip spring sale, save up to $1,100 on our unique small-group trips limited spots..

- Post ID: 1702695

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

What was the Grand Tour?

Find out about the travel phenomenon that became popular amongst the young nobility of England

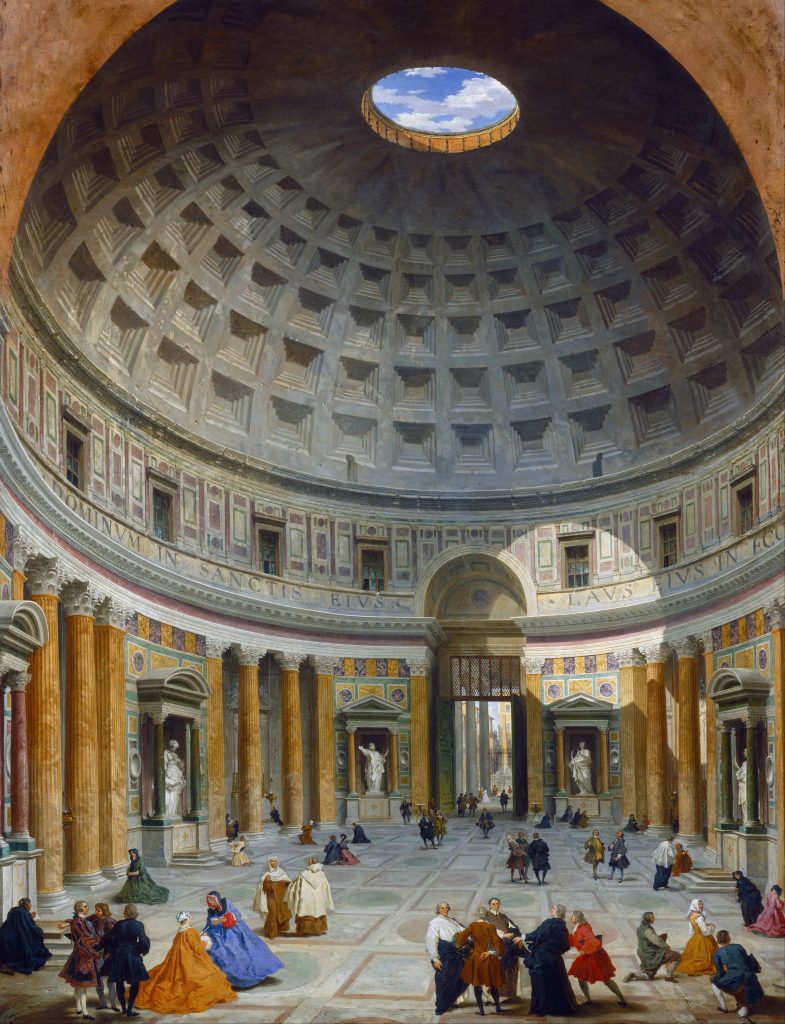

Art, antiquity and architecture: the Grand Tour provided an opportunity to discover the cultural wonders of Europe and beyond.

Popular throughout the 18th century, this extended journey was seen as a rite of passage for mainly young, aristocratic English men.

As well as marvelling at artistic masterpieces, Grand Tourists brought back souvenirs to commemorate and display their journeys at home.

One exceptional example forms the subject of a new exhibition at the National Maritime Museum. Canaletto’s Venice Revisited brings together 24 of Canaletto’s Venetian views, commissioned in 1731 by Lord John Russell following his visit to Venice.

Find out more about this travel phenomenon – and uncover its rich cultural legacy.

Canaletto's Venice Revisited

The origins of the Grand Tour

The development of the Grand Tour dates back to the 16th century.

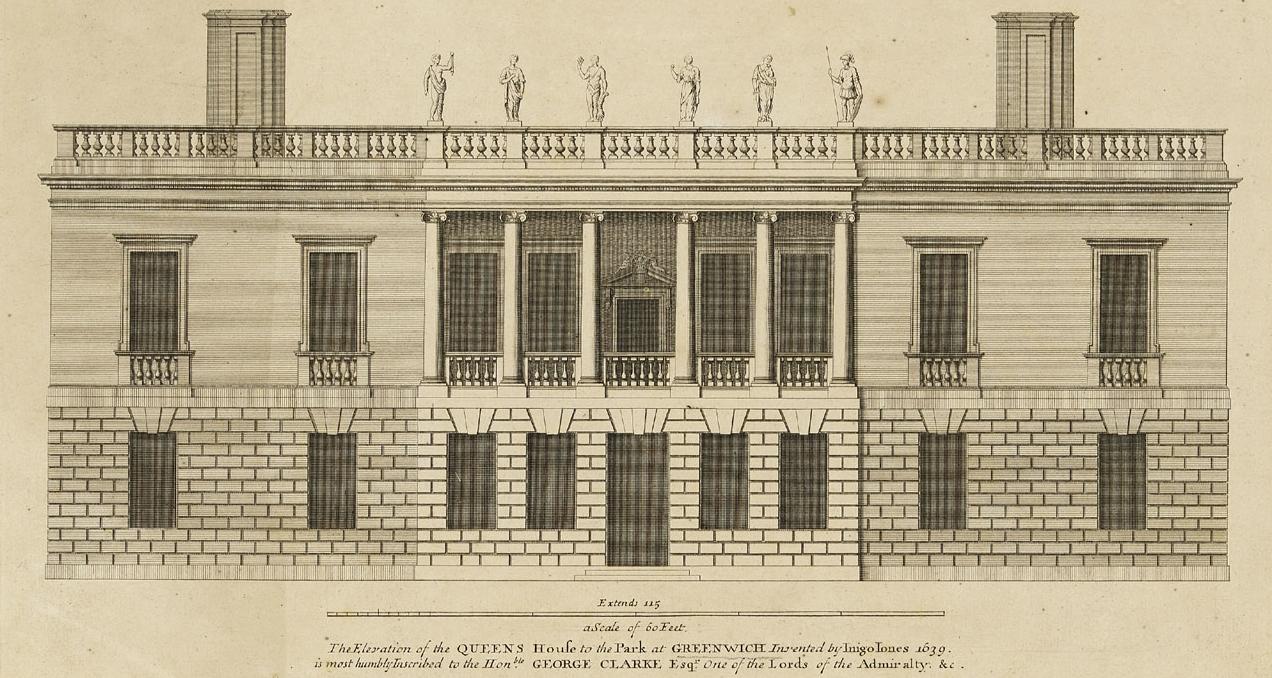

One of the earliest Grand Tourists was the architect Inigo Jones , who embarked on a tour of Italy in 1613-14 with his patron Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel.

Jones visited cities such as Parma, Venice and Rome. However, it was Naples that proved the high point of his travels.

Jones was particularly fascinated by the San Paolo Maggiore, describing the church as “one of the best things that I have ever seen.”

Jones’s time in Italy shaped his architectural style. In 1616, Jones was commissioned to design the Queen’s House in Greenwich for Queen Anne of Denmark , the wife of King James I. Completed in around 1636, the house was the first classical building in England.

The expression ‘Grand Tour’ itself comes from 17th century travel writer and Roman Catholic priest Richard Lassels, who used it in his guidebook The Voyage of Italy, published in 1670.

By the 18th century, the Grand Tour had reached its zenith. Despite Anglo-French wars in 1689-97 and 1702-13, this was a time of relative stability in Europe, which made travelling across the continent easier.

The Grand Tour route

For young English aristocrats, embarking on the Grand Tour was seen as an important rite of passage.

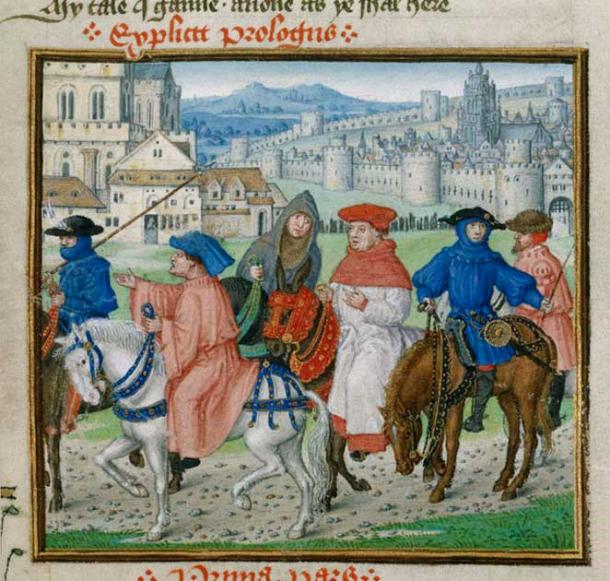

Accompanied by a tutor, a Grand Tourist’s route typically involved taking a ship across the English Channel before travelling in a carriage through France, stopping at Paris and other major cities.

Italy was also a popular destination thanks to the art and architecture of places such as Venice, Florence, Rome, Milan and Naples. More adventurous travellers ventured to Sicily or even sailed across to Greece. The average Grand Tour lasted for at least a year.

As Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art at Royal Museums Greenwich explains, this extended journey marked the culmination of a Grand Tourist’s education.

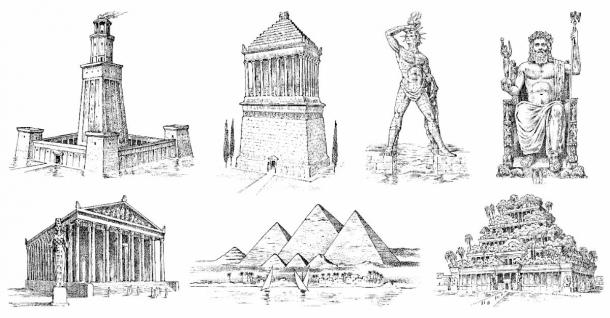

“The Grand Tourists would have received an education that was grounded in the Classics,” she says. “During their travels to the continent, they would have seen classical ruins and read Latin and Greek texts. The Grand Tour was also an opportunity to take in more recent culture, such as Renaissance paintings, and see contemporary artists at work.”

As well as educational opportunities, the Grand Tour was linked with independence. Places such as Venice were popular with pleasure seekers, boasting gambling houses and occasions for drinking and partying.

“On the Grand Tour, there’s a sense that travellers are gaining some of their independence and having a lesson in the ways of the world,” Gazzard explains. “For visitors to Venice, there were opportunities to behave beyond the social norms, with the masquerade and the carnival.”

Art and the Grand Tour

Bound up with the idea of independence was the need to collect souvenirs, which the Grand Tourists could display in their homes.

“The ownership of property was tied to status, so creating a material legacy was really important for the Grand Tourists in order to solidify their social standing amongst their peers,” says Gazzard. “They were looking to spend money and buy mementos to prove they went on the trip.”

The works of artists such as those of the 18th century view painter Giovanni Antonio Canal (known as Canaletto ) were especially popular with Grand Tourists. Prized for their detail, Canaletto’s artworks captured the landmarks and scenes of everyday Venetian life, from festive scenes to bustling traffic on the Grand Canal .

In 1731, Lord John Russell, the future 4th Duke of Bedford, commissioned Canaletto to create 24 Venetian views following his visit to the city.

Lord John Russell is known to have paid at least £188 for the set – over five times the annual earnings of a skilled tradesperson at the time.

“Canaletto’s work was portable and collectible,” says Gazzard. “He adopted a smaller size for his canvases so they could be rolled up and shipped easily.”

These detailed works, now part of the world famous collection at Woburn Abbey, form the centrepiece of Canaletto’s Venice Revisited at the National Maritime Museum .

Who was Canaletto?

The legacy of the Grand Tour

The start of the French Revolution in 1789 marked the end of the Grand Tour. However, its legacy is still keenly felt.

The desire to explore and learn about different places and cultures through travel continues to endure. The legacy of the Grand Tour can also be seen in the artworks and objects that adorn the walls of stately homes and museums, and the many cultural influences that travellers brought back to Britain.

Canaletto's Venice Revisited

Main image: The Piazza San Marco looking towards the Basilica San Marco and the Campanile by Canaletto . From the Woburn Abbey Collection . Canaletto painting in body copy: Regatta on Grand Canal by Canaletto From the Woburn Abbey Collection

18th Century Grand Tour of Europe

The Travels of European Twenty-Somethings

Print Collector/Getty Images

- Key Figures & Milestones

- Physical Geography

- Political Geography

- Country Information

- Urban Geography

- M.A., Geography, California State University - Northridge

- B.A., Geography, University of California - Davis

The French Revolution marked the end of a spectacular period of travel and enlightenment for European youth, particularly from England. Young English elites of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries often spent two to four years touring around Europe in an effort to broaden their horizons and learn about language , architecture , geography, and culture in an experience known as the Grand Tour.

The Grand Tour, which didn't come to an end until the close of the eighteenth century, began in the sixteenth century and gained popularity during the seventeenth century. Read to find out what started this event and what the typical Tour entailed.

Origins of the Grand Tour

Privileged young graduates of sixteenth-century Europe pioneered a trend wherein they traveled across the continent in search of art and cultural experiences upon their graduation. This practice, which grew to be wildly popular, became known as the Grand Tour, a term introduced by Richard Lassels in his 1670 book Voyage to Italy . Specialty guidebooks, tour guides, and other aspects of the tourist industry were developed during this time to meet the needs of wealthy 20-something male and female travelers and their tutors as they explored the European continent.

These young, classically-educated Tourists were affluent enough to fund multiple years abroad for themselves and they took full advantage of this. They carried letters of reference and introduction with them as they departed from southern England in order to communicate with and learn from people they met in other countries. Some Tourists sought to continue their education and broaden their horizons while abroad, some were just after fun and leisurely travels, but most desired a combination of both.

Navigating Europe

A typical journey through Europe was long and winding with many stops along the way. London was commonly used as a starting point and the Tour was usually kicked off with a difficult trip across the English Channel.

Crossing the English Channel

The most common route across the English Channel, La Manche, was made from Dover to Calais, France—this is now the path of the Channel Tunnel. A trip from Dover across the Channel to Calais and finally into Paris customarily took three days. After all, crossing the wide channel was and is not easy. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Tourists risked seasickness, illness, and even shipwreck on this first leg of travel.

Compulsory Stops

Grand Tourists were primarily interested in visiting cities that were considered major centers of culture at the time, so Paris, Rome, and Venice were not to be missed. Florence and Naples were also popular destinations but were regarded as more optional than the aforementioned cities.

The average Grand Tourist traveled from city to city, usually spending weeks in smaller cities and up to several months in the three major ones. Paris, France was the most popular stop of the Grand Tour for its cultural, architectural, and political influence. It was also popular because most young British elite already spoke French, a prominent language in classical literature and other studies, and travel through and to this city was relatively easy. For many English citizens, Paris was the most impressive place visited.

Getting to Italy

From Paris, many Tourists proceeded across the Alps or took a boat on the Mediterranean Sea to get to Italy, another essential stopping point. For those who made their way across the Alps, Turin was the first Italian city they'd come to and some remained here while others simply passed through on their way to Rome or Venice.

Rome was initially the southernmost point of travel. However, when excavations of Herculaneum (1738) and Pompeii (1748) began, these two sites were added as major destinations on the Grand Tour.

Features of the Grand Tour

The vast majority of Tourists took part in similar activities during their exploration with art at the center of it all. Once a Tourist arrived at a destination, they would seek housing and settle in for anywhere from weeks to months, even years. Though certainly not an overly trying experience for most, the Grand Tour presented a unique set of challenges for travelers to overcome.

While the original purpose of the Grand Tour was educational, a great deal of time was spent on much more frivolous pursuits. Among these were drinking, gambling, and intimate encounters—some Tourists regarded their travels as an opportunity to indulge in promiscuity with little consequence. Journals and sketches that were supposed to be completed during the Tour were left blank more often than not.

Visiting French and Italian royalty as well as British diplomats was a common recreation during the Tour. The young men and women that participated wanted to return home with stories to tell and meeting famous or otherwise influential people made for great stories.

The study and collection of art became almost a nonoptional engagement for Grand Tourists. Many returned home with bounties of paintings, antiques, and handmade items from various countries. Those that could afford to purchase lavish souvenirs did so in the extreme.

Arriving in Paris, one of the first destinations for most, a Tourist would usually rent an apartment for several weeks or months. Day trips from Paris to the French countryside or to Versailles (the home of the French monarchy) were common for less wealthy travelers that couldn't pay for longer outings.

The homes of envoys were often utilized as hotels and food pantries. This annoyed envoys but there wasn't much they could do about such inconveniences caused by their citizens. Nice apartments tended to be accessible only in major cities, with harsh and dirty inns the only options in smaller ones.

Trials and Challenges

A Tourist would not carry much money on their person during their expeditions due to the risk of highway robberies. Instead, letters of credit from reputable London banks were presented at major cities of the Grand Tour in order to make purchases. In this way, tourists spent a great deal of money abroad.

Because these expenditures were made outside of England and therefore did not bolster England's economy, some English politicians were very much against the institution of the Grand Tour and did not approve of this rite of passage. This played minimally into the average person's decision to travel.

Returning to England

Upon returning to England, tourists were meant to be ready to assume the responsibilities of an aristocrat. The Grand Tour was ultimately worthwhile as it has been credited with spurring dramatic developments in British architecture and culture, but many viewed it as a waste of time during this period because many Tourists did not come home more mature than when they had left.

The French Revolution in 1789 halted the Grand Tour—in the early nineteenth century, railroads forever changed the face of tourism and foreign travel.

- Burk, Kathleen. "The Grand Tour of Europe". Gresham College, 6 Apr. 2005.

- Knowles, Rachel. “The Grand Tour.” Regency History , 30 Apr. 2013.

- Sorabella, Jean. “The Grand Tour.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History , The Met Museum, Oct. 2003.

- A Beginner's Guide to the Enlightenment

- Architecture in France: A Guide For Travelers

- The History of Venice

- A Brief History of Rome

- The Best Books on Early Modern European History (1500 to 1700)

- What Is a Monarchy?

- The Top 10 Major Cities in France

- A Beginner's Guide to the Renaissance

- Female European Historical Figures: 1500 - 1945

- Renaissance Architecture and Its Influence

- 8 Major Events in European History

- The 12 Best Books on the French Revolution

- William Turner, English Romantic Landscape Painter

- Architecture in Italy for the Lifelong Learner

- 18 Key Thinkers of the Enlightenment

- Hispanic Surnames: Meanings, Origins and Naming Practices

The lavish Grand Tours of history — and how they shaped the way we travel today

It was a rite of passage for young, upper-class Englishmen with virtually unlimited money to burn — a hedonistic "Grand Tour" far from home, unfolding over two or three or even four years.

Designed to teach them about art, history and culture, it was a kind of finishing school that would ready them for life in the powerful ruling elite.

Unsurprisingly, sex, gambling, drinking, and lavish parties also found their way into the mix.

For many historians, these travellers of the 17th and 18th centuries represent the first modern tourists.

They fuelled a passion for adventure and paved the way for the type of travel we know (and miss) today.

The ultimate destinations

The Grand Tour began in about 1660 and reached its zenith between 1748 and 1789.

It was typically undertaken by men aged between 18 and 25 — the sons of the aristocracy.

First, they braved the English Channel to reach Belgium or France. There, many purchased a carriage for the onward journey.

They were accompanied by a guide, known as a "bear-leader", who tutored them in art, music, literature and history.

If they were wealthy enough, their entourage included a troop of servants.

While there was no fixed route, most tours included the great cities of Europe — Paris, Geneva, Berlin — and a lengthy sojourn in Italy.

"A man who has not been in Italy is always conscious of an inferiority, from his not having seen what it is expected a man should see," English author Samuel Johnson remarked in 1776.

Rome was considered the ultimate destination, but Venice, Florence, Milan and Naples were also high on the list.

A drive for education and enlightenment was at the heart of the tour.

The Grand Tourists looked at art, admired monuments, visited historical sites, and studied classical architecture. They mingled with the elite social classes.

Behaving badly

They were students with practically unlimited budgets, and often very little supervision.

European history expert Eric Zuelow says this meant they were "apt to behave in a rather different way with rather different interests than the Grand Tour was designed to instil in them".

"So what they tended to do was to go and drink a lot, to gamble, to frequent [sex workers]," he tells ABC RN's Rear Vision .

"They tended not to learn much in the way of languages, not to learn much in the way of culture, but to have a lot of fun.

"And that created, I would argue, really one of the first instances of the notion of tourists as being lesser creatures and travellers being something much better.

"The first tourists, the Grand Tourists, did not behave all that well. And tourists have held that stigma ever since."

It wasn ' t all smooth sailing

In the days of the Grand Tour, travel wasn't for the faint-hearted.

There are many reports of the young men becoming ill from travel sickness, rough seas and foreign foods.

Disease was another threat — during his Grand Tour, writer John Evelyn nearly died of smallpox in Geneva.

Thieves were highly active, so many Grand Tourists didn't carry cash, instead taking the equivalent of travellers' cheques.

Roads were rough and full of potholes, and the carriages could only journey about 20 kilometres a day. Some parts of the trip were undertaken by foot.

"So they could be weeks just getting from one place to another," says historian Susan Barton.

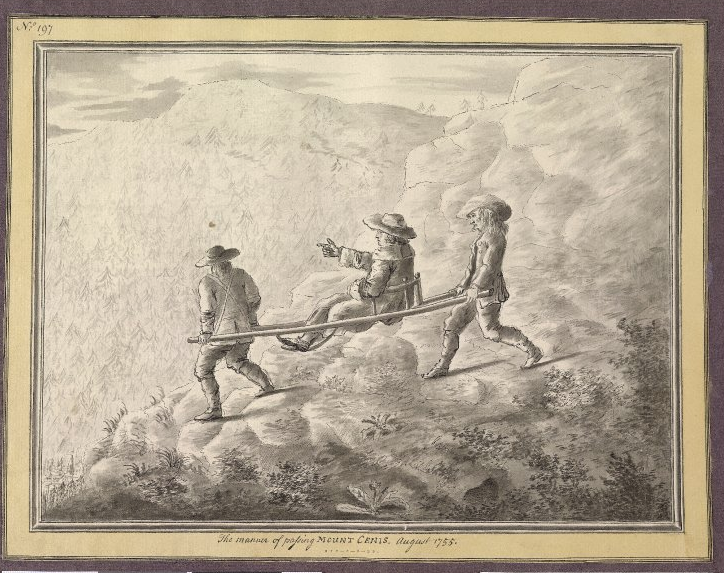

Crossing the Alps was a particular challenge.

Some Grand Tourists hired a sedan chair to be carried, literally, over the mountain passes.

The "chairmen of Mont Cenis" became known throughout the Alps for their strength and dexterity.

The rise of 'self-illusory hedonistic consumption'

These early travellers carried guidebooks, which advised them of what to see, hear and do.

They were told to show their wealth at every turn, to garner respect.

As time went by, those making the Grand Tour also became shoppers. They wanted to buy things they could later show off.

"What was happening at this time was a development of what one scholar called 'self-illusory hedonistic consumption', which is a really fancy term for spending money because buying things will make you better," Professor Zuelow says.

"The Grand Tour, with its original educational roots, merged with that self-illusory, hedonistic idea, creating a consumable."

The young tourists would return to England with bulging luggage — marble statues from Rome, colourful glassware from Venice, pumice stone from Naples.

They brought back paintings depicting the Colosseum in Rome, the canals in Venice, the Parthenon in Athens.

They'd also commission portraits of themselves, and a mini industry sprung up around this.

It wasn't just to remind themselves of all they had seen and done. It was so other people would also know.

The souvenirs were displayed with great pride in the family's estates and manor houses.

"And later some of those things ended up in museums," Dr Barton says.

"So in a way they were creating the future 20th century tourism where people were visiting country houses as part of their leisure."

Not all Britons — and not all men

Although Britons far outnumbered all others, Professor Zuelow notes that they weren't the only Grand Tourists.

Peter the Great, the Russian Tsar, famously made the trip, as did German philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and King Gustav III of Sweden.

And it also wasn't just men.

Professor Zuelow says English women such as author Mary Wollstonecraft and socialite Lady Mary Wortley Montagu spent extensive time in Europe, enjoying new freedoms and the chance for an education not available to them back home.

Travel for leisure and the Grand Tour's legacy

By 1815, the Grand Tour was disappearing.

Professor Zuelow says part of the reason for this is obvious: the French Revolution, followed closely by the Napoleonic Wars, swept across Europe starting in 1789 and extended until 1815.

"When the fighting stopped, many visitors returned — even if only to see the damages of war — but this was no longer the old Grand Tour," he writes in his book, A History of Modern Travel.

After 1815, travel to Europe slowly opened up for much wider social groups.

"So rather than just the aristocracy, we've got middle class people starting to travel, but it was still quite a lengthy process," Dr Barton says.

The legacy of the Grand Tour lives on to this day.

It still influences the destinations we visit, and has shaped the ideas of culture and sophistication that surround the act of travel.

It shaped the notion that there's something to be gained from venturing overseas, that there's a lot on offer if you can leave home to find it.

"Prior to the Grand Tour, there wasn't a lot of travel for leisure," Professor Zuelow says.

"Medieval pilgrims have been put forward as possible tourists but they were travelling for religious purposes. And although they had a lot of fun along the way, it really was about getting into Heaven."

Many of the Grand Tourists wrote about their adventures, fuelling a new level of wanderlust in society.

The trips were the stuff of fantasy, and others wanted to follow.

It was a first step in the direction of mass tourism, and the kind of travel we know today.

"I define it really as travelling for the purpose of travelling, travelling for fun, travelling for enjoyment, feeling that travel is going to make you healthier and happier and a better person," Professor Zuelow says.

To hear more about the history of travel, the impact of technology on tourism, and the future may hold, listen to ABC Radio National's Rear Vision podcast .

RN in your inbox

Get more stories that go beyond the news cycle with our weekly newsletter.

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

Pay with a credit card, and other tips to covid-proof your next holiday.

It's so bad Qantas is selling its pyjamas — but flying's new reality is not as grim

Guide Alice and the 'sleeping buffalo' that stole her heart

- Community and Society

- European Union

- Human Interest

- Lifestyle and Leisure

- Travel and Tourism (Lifestyle and Leisure)

- United Kingdom

- United States

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

What Was the Grand Tour of Europe?

Lucy Davidson

26 jan 2022, @lucejuiceluce.

In the 18th century, a ‘Grand Tour’ became a rite of passage for wealthy young men. Essentially an elaborate form of finishing school, the tradition saw aristocrats travel across Europe to take in Greek and Roman history, language and literature, art, architecture and antiquity, while a paid ‘cicerone’ acted as both a chaperone and teacher.

Grand Tours were particularly popular amongst the British from 1764-1796, owing to the swathes of travellers and painters who flocked to Europe, the large number of export licenses granted to the British from Rome and a general period of peace and prosperity in Europe.

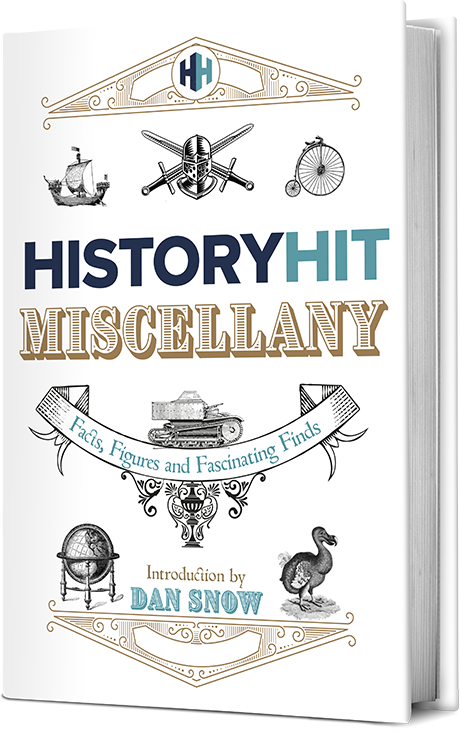

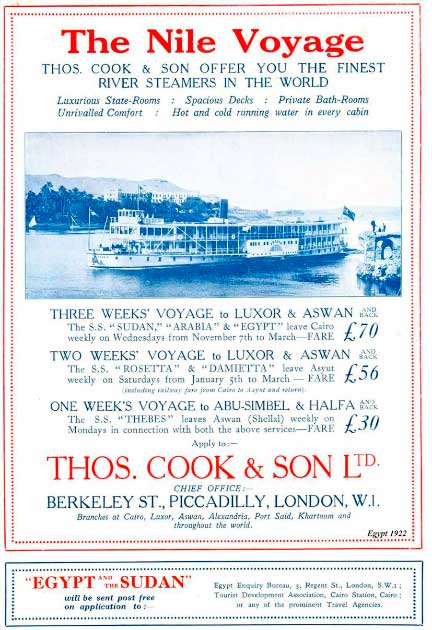

However, this wasn’t forever: Grand Tours waned in popularity from the 1870s with the advent of accessible rail and steamship travel and the popularity of Thomas Cook’s affordable ‘Cook’s Tour’, which made mass tourism possible and traditional Grand Tours less fashionable.

Here’s the history of the Grand Tour of Europe.

Who went on the Grand Tour?

In his 1670 guidebook The Voyage of Italy , Catholic priest and travel writer Richard Lassells coined the term ‘Grand Tour’ to describe young lords travelling abroad to learn about art, culture and history. The primary demographic of Grand Tour travellers changed little over the years, though primarily upper-class men of sufficient means and rank embarked upon the journey when they had ‘come of age’ at around 21.

‘Goethe in the Roman Campagna’ by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein. Rome 1787.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Grand Tours also became fashionable for women who might be accompanied by a spinster aunt as a chaperone. Novels such as E. M. Forster’s A Room With a View reflected the role of the Grand Tour as an important part of a woman’s education and entrance into elite society.

Increasing wealth, stability and political importance led to a more broad church of characters undertaking the journey. Prolonged trips were also taken by artists, designers, collectors, art trade agents and large numbers of the educated public.

What was the route?

The Grand Tour could last anything from several months to many years, depending on an individual’s interests and finances, and tended to shift across generations. The average British tourist would start in Dover before crossing the English Channel to Ostend in Belgium or Le Havre and Calais in France. From there the traveller (and if wealthy enough, group of servants) would hire a French-speaking guide before renting or acquiring a coach that could be both sold on or disassembled. Alternatively, they would take the riverboat as far as the Alps or up the Seine to Paris .

Map of grand tour taken by William Thomas Beckford in 1780.

From Paris, travellers would normally cross the Alps – the particularly wealthy would be carried in a chair – with the aim of reaching festivals such as the Carnival in Venice or Holy Week in Rome. From there, Lucca, Florence, Siena and Rome or Naples were popular, as were Venice, Verona, Mantua, Bologna, Modena, Parma, Milan, Turin and Mont Cenis.

What did people do on the Grand Tour?

A Grand Tour was both an educational trip and an indulgent holiday. The primary attraction of the tour lay in its exposure of the cultural legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance, such as the excavations at Herculaneum and Pompeii, as well as the chance to enter fashionable and aristocratic European society.

Johann Zoffany: The Gore Family with George, third Earl Cowper, c. 1775.

In addition, many accounts wrote of the sexual freedom that came with being on the continent and away from society at home. Travel abroad also provided the only opportunity to view certain works of art and potentially the only chance to hear certain music.

The antiques market also thrived as lots of Britons, in particular, took priceless antiquities from abroad back with them, or commissioned copies to be made. One of the most famous of these collectors was the 2nd Earl of Petworth, who gathered or commissioned some 200 paintings and 70 statues and busts – mainly copies of Greek originals or Greco-Roman pieces – between 1750 and 1760.

It was also fashionable to have your portrait painted towards the end of the trip. Pompeo Batoni painted over 175 portraits of travellers in Rome during the 18th century.

Others would also undertake formal study in universities, or write detailed diaries or accounts of their experiences. One of the most famous of these accounts is that of US author and humourist Mark Twain, whose satirical account of his Grand Tour in Innocents Abroad became both his best selling work in his own lifetime and one of the best-selling travel books of the age.

Why did the popularity of the Grand Tour decline?

A Thomas Cook flyer from 1922 advertising cruises down the Nile. This mode of tourism has been immortalised in works such as Death on the Nile by Agatha Christie.

The popularity of the Grand Tour declined for a number of reasons. The Napoleonic Wars from 1803-1815 marked the end of the heyday of the Grand Tour, since the conflict made travel difficult at best and dangerous at worst.

The Grand Tour finally came to an end with the advent of accessible rail and steamship travel as a result of Thomas Cook’s ‘Cook’s Tour’, a byword of early mass tourism, which started in the 1870s. Cook first made mass tourism popular in Italy, with his train tickets allowing travel over a number of days and destinations. He also introduced travel-specific currencies and coupons which could be exchanged at hotels, banks and ticket agencies which made travelling easier and also stabilised the new Italian currency, the lira.

As a result of the sudden potential for mass tourism, the Grand Tour’s heyday as a rare experience reserved for the wealthy came to a close.

Can you go on a Grand Tour today?

Echoes of the Grand Tour exist today in a variety of forms. For a budget, multi-destination travel experience, interrailing is your best bet; much like Thomas Cook’s early train tickets, travel is permitted along many routes and tickets are valid for a certain number of days or stops.

For a more upmarket experience, cruising is a popular choice, transporting tourists to a number of different destinations where you can disembark to enjoy the local culture and cuisine.

Though the days of wealthy nobles enjoying exclusive travel around continental Europe and dancing with European royalty might be over, the cultural and artistic imprint of a bygone Grand Tour era is very much alive.

To plan your own Grand Tour of Europe, take a look at History Hit’s guides to the most unmissable heritage sites in Paris , Austria and, of course, Italy .

You May Also Like

Mac and Cheese in 1736? The Stories of Kensington Palace’s Servants

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

Gerrit Verhoeven is assistant professor in cultural heritage and history at the University of Antwerp. He is also archivist and research fellow at the Royal Museums of Art and History (Brussels).

- Published: 18 August 2022

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Our present-day understanding of the classic Grand Tour hovers between identification and estrangement. On the one hand, there is a tendency among scholars to tone down the differences between early modern travel and modern tourism. Focusing on apparent similarities—the fascination for Michelangelo’s Last Judgment , the burgeoning tourism industry, the craving for souvenirs, and so on—the Grand Tour traveler becomes a tourist avant la lettre . On the other hand, there is also a strand to maximize the differences by emphasizing the danger and discomfort involved. Focusing on highwaymen and pirates, spectacular accidents, religious intolerance, epidemic diseases, and other calamities, a black-and-white opposition is created between our bland vacationing and its more spectacular premodern variant. To move beyond these classic, binary storylines on the Grand Tour, a more evolutionary lens will be explored here. How did early modern travel evolve in terms of space and time, the social profile of the travelers, and their motivations?

Even though the early modern Grand Tour and modern tourism are etymologically associated terms, the precise relationship between them remains under discussion. Opinions oscillate between identification and alienation. Especially in the last decades of the twenty-first century, academics felt the urge to portray the Grand Tour as an early, yet unquestionably modern, forerunner of tourism. They usually stressed ready-made similarities: the fact that Rome, Florence, and other destinations are still as popular as they were centuries ago, the lasting hype surrounding Michelangelo’s Last Judgment , Bernini’s Apollo & Daphne , and (less convincingly) Vivaldi’s Four Seasons ; the unchanging, and deeply human, passion for good wine, exquisite food, or unrestrained sex abroad; the ageless hunt for tawdry souvenirs and other mementos; the bawdy graffiti on monuments; and other resemblances. On account of these apparent parallels, early modern travel is increasingly labeled as tourism, even by academic experts. 1 On the other hand, a strong feeling of estrangement reigns supreme: it is a trope that frequently crops up in older books on the Grand Tour, whereby early modern travel behavior is often depicted as an obscure predecessor—or even antipode—of modern tourism. Significant differences include the large risks and huge discomfort involved in traveling—including merciless highwaymen, spectacular accidents, shabby inns, inedible food, and other calamities—the stern, humanistic rationale of the Grand Tour, the exclusive pedigree of the travelers with a train of servants, and other stereotypes. 2

Both opinions have their advocates and are viable as an economic strategy for selling more books because a master narrative, premised on easy binaries, strongly appeals to readers’ imaginations. Yet such accounts might also cloud our understanding of the actual Grand Tour. The historical reality was much more complex, multilayered, and versatile than cardboard cut-outs suggest. Discussions are further complicated by the fact that a classic definition of what the Grand Tour actually entailed remains missing. Vexed by the loose interpretation of some of his colleagues, Bruce Redford dotted the i’s and crossed the t’s in his book on Venice and the Grand Tour :

the Grand Tour is not the Grand Tour unless it includes the following: a young British male patrician (that is, a member of the aristocracy of the gentry); second, a tutor who accompanies his charge throughout the journey; third, a fixed itinerary that makes Rome its principal destination; fourth, a lengthy period of absence, averaging two or three years. 3

A recent upsurge in research renders Redford’s strict interpretation obsolete, as a virtually endless series of books now shows that the Grand Tour was anything but an exclusively British phenomenon. French, German, Dutch, Swedish, Polish, and other European travelers were also drawn to Rome, although their own interpretations could differ significantly from the British prototype. 4 Moreover, research shows that the praxis of the Grand Tour was much more versatile than Redford’s definition suggests. From its dawn in the late sixteenth century until its crepuscule in the early nineteenth century, the classic Grand Tour saw radical changes in its spatial layout and timing, as well as in the social profile of travelers and their motivations. 5

Space was essential to the understanding of a classic Grand Tour; the trip was structured around a more-or-less fixed, circular itinerary, which was primarily geared toward Italy and France. Travelers only skirted the fringes of the Holy Roman Empire, Switzerland, or England (boiled down to London), while the Iberian Peninsula, Scandinavia, and Eastern Europe were largely ignored. Conformism also reigned supreme on a lower level: in Italy a set of large cities, including Rome, Florence, Venice, Naples, and Bologna, and a string of smaller towns formed the backbone of the classic Grand Tour, 6 while in France, attention was firmly focused on Paris and on the “Small Tour” (literally Kleene Tour in Dutch), a long circular journey along the Loire to Aquitaine, the Languedoc, and Provence, and back to Paris via the river Rhône. 7 On their return journey, travelers also frequently crossed the border to Geneva, the bulwark of Calvinism, sailed down the river Rhine, or paid a quick visit to the Netherlands. A classic Grand Tour was in principle an urban experience: travelers did not focus on the landscape between the cities except for some scattered notes on the fertile meadows and fields in the Po valley, along the Loire, or in the Dutch polders . 8 Conformism was fueled by a whole spectrum of factors, ranging from the lofty, yet coercive, instructions of humanist sages on what to see and do—the so-called Artes Apodemic or how-to books about the art of traveling—to the sprawl of early guidebooks, to the basic transport infrastructure, whereby travelers followed the well-trodden trail of the postal services. 9

These itineraries were not written in stone. They were not only affected by eventful blips—wars, pestilence, revolution, religious policies—but also by more structural changes. From the late seventeenth century onwards, the spatial blueprint of the classic Grand Tour was redrawn. First of all, there was a process of contraction, as the sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century longlist of must-do destinations was gradually boiled down to its essence. Eighteenth-century travelers still focused on Florence, Venice, Rome, and other important Italian cities, while smaller towns were increasingly traversed in a tearing rush or simply cut from the program. The same held true for France. Grand Tour travelers increasingly shunned the long detour through the provinces and focused almost entirely on the capital. 10 Paris’s rise hints at a second important evolution. During the early eighteenth century, the compass of Grand Tour travelers shifted northward. Rome still remained the ultimate goal, but in its wake, the new metropolises of the North—Paris, London, Amsterdam, and even Berlin—were on the ascent. Whereas in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, they had served as a hearty appetizer—or dessert—for the cultural bliss of Italy, they were destinations in their own right by the late eighteenth century. 11 Last but not least, the Grand Tour lost its urban focus on the eve of the French Revolution. Travelers increasingly included a detour to the Swiss Alps in their return trip, while a cours pittoresque along the Rhine—savoring the landscape with towering rock-faces, wooded bluffs, whirling rapids, lush vineyards, and other romantic elements—became the classic terminus of the Grand Tour in the early nineteenth century. 12

Even though experts have begun to trace these topographical changes in detail, little was known about underlying causes. It is assumed that the program of the Grand Tour, and its grid of destinations and itineraries, was reshuffled by a complex set of internal factors (the changing profile of the travelers and their motivations, as well as the timing of the Grand Tour) and external causes (cultural patronage, economic growth, and transport infrastructure). For the latter, it is likely that the rule of Louis XIV, who tried to turn Paris into the New Rome through an ambitious program of urban renewal, upset the balance, which had, traditionally, tilted toward Italy. Monumental architecture, statues, squares, and parks were built; new museums, libraries, and other collections were founded; the opera, theater, ballet, science, and myriad other cultural initiatives were fostered. Louis’s patronage was followed with Argus’s eyes all over Europe and blindly copied, smartly adapted, or even completely outstripped by other rulers, whereby the cityscapes of London, Dresden, Vienna, Turin, and other European cities were transformed. 13 At the same time, the rise of these northern metropolises was powered by their economic growth, as the epicenter began to shift from Mediterranean to Atlantic shores. Owing to their economic boom, London, Amsterdam, Paris, and other northern cities became much more attractive in the late seventeenth and eighteenth century, as culture (architecture, painting, music, sculpture) thrived in the slipstream of the economic expansion. 14

Travelers increasingly experienced Florence, Rome, Venice, and other Italian cities as hollow shells, ancient, museum-like theme-parks of Roman antiquity and Renaissance culture that stood in stark contrast to the vibrancy and modern feel of London, Paris, and other northern metropolises. 15 The balance was tipped by a silent transport (r)evolution. Transport and travel had become much easier, less risky, and more comfortable by the early seventeenth century owing to the spread of postal networks and coach services, but gained momentum as a result of late seventeenth-century innovations when a network of paved roads radiated from London, Paris, Brussels, and other capitals in Northwest Europe. At the same time, tow-boat and barge services facilitated easier access to the Dutch Republic and operated along the Rhine. An increasing number of ferries and packet-boats crossed the Channel. 16

Transport innovations, cultural patronage, and economic growth not only distorted the warp and weft of the early modern travel map, but also frayed its fabric, as travelers were now able to bead a set of absolute must-see destinations together, while the less attractive towns in between could simply be skipped. During the nineteenth century, the process was intensified by the advent of steam power (see Pearson , this volume). It ultimately sounded the knell of the classic Grand Tour, as steamboats, trains, and other transport innovations had made the classic, circular journey through Europe obsolete. Linear trips—boarding a train in Victoria Station, le Gare du Midi , or in The Hague, Hollands Spoor , and disembarking in Florence, Milan, or Rome—were the future.

Time was also an essential component of the Grand Tour, as the classic journey to France, Italy, and Switzerland could easily take two or three years in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth centuries. Owing to its exceptional length, the journey was often cast as a once-in-a-lifetime experience or, to use Arnold van Gennep’s famous anthropological concept, a rite de passage (rite of passage) between youth and adulthood. All the ingredients were there: a long separation from home, complex rituals upon leave and return, and a physical/psychological test to prove one’s maturity. 17 New research has shown that travelers also came home with saddlebags filled with spurs, swords, stately garb, portraits, books, and other highly symbolic objects that marked the transition from adolescence to adulthood. 18 The length of the journey could take a serious emotional toll, as travelers were frequently overcome by homesickness and melancholia on their long peregrinations in Italy; yet, despite the recent, late twentieth-century emotional turn in the field of history, research that focuses on this “dark side” of the Grand Tour remains scarce. Drawing on British letters and travel diaries, Sarah Goldsmith raised a tip of the veil, as the correspondence home was often brimming with strong, yet tacit, feelings of homesickness, although the ideal of polite masculinity required some moderation. Feelings of melancholia were actively counteracted by regular correspondence with the home front and the exchange of news, gossip, and presents. 19

During the eighteenth century, travel time was drastically reduced, because stone-slab paved roads, regular coach services, and comfy barges radically increased the speed of travel. As a result, the time span needed for a full-blown Grand Tour decreased from some years to some months in the late eighteenth century. 20 Not only did the reduction have far-reaching consequences for the social profile of the Grand Tour traveler but it also changed the symbolic value of the journey as a rite de passage . At the close of the eighteenth century, the number of travelers who were able to launch upon several trips to Italy—and by then also to Sicily, Greece, the Middle East, and other regions—was clearly in the ascendancy. It sapped the idea of travel as a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Nineteenth century tourism increasingly became a recurrent praxis.

The social composition of the classical Grand Tour changed dramatically. During the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, the journey to Italy was, indeed, as Redford argues, largely reserved for male scions of extremely wealthy noble families, even if the precise composition was highly dependent on regional differences. British, French, and German Grand Tour travelers were often nobles or gentry, 21 while the Dutch variant was much more bourgeois. Yet, even in this case, travelers came predominantly from the upper-crust of Amsterdam, Leiden, and Hague mercantile elites. 22 Most Grand Tour travelers were relatively young—somewhere between eighteen and thirty—which was logical considering the exceptional length of the classic Grand Tour made it (almost) incompatible with a career, a marriage, and other burdens of adult life. Therefore, it was often cast as a rite of passage into adulthood. 23 In addition to lots of time, loads of money were needed to complete the journey in style, which made a Grand Tour the privilege of the rich and the famous, who often traveled with a retinue. 24

In the late 2010s, new research has added some color and depth to this rather one-dimensional, black-and-white portrait. Trailblazing is, for instance, the work of Richard Ansell, who explored the decision-making behind the scenes in Ireland. Families did not always send their firstborn on a Grand Tour, but often favored their second or third son to enhance their future career prospects. Decisions about whom to send on a full-fledged Grand Tour, on a more modest trip to the continent, or even more simply, to a French academy in London were not only based on careful calculations of the family’s financial resources, but also tailored to specific educational needs, career opportunities, and personal traits. 25 T wenty-first-century research does not only shed light on the main character of the Grand Tour, the traveler, but has also uncovered valuable details about the lives of background characters. Little was known about the scores of governors (nicknamed bearleaders ) and servants, who followed their master on the Grand Tour. In recent years, however, their travel experiences have been put under the microscope. 26

This fact hints at a broader tendency in the historiography of the Grand Tour that has been profoundly influenced by gender history. Female historians, at first, went through travel journals, diaries, and letters with a fine-tooth comb and found a wealth of manuscripts written by women that had been largely ignored or shoved aside by their male colleagues. Even more numerous were the travel journals that had been written by men, but where women were part of the travel party. Rosemary Sweet and others have tried to restore the balance in recent years. Especially in the eighteenth century, female travelers were on the rise, as it was no longer frowned upon that women joined their husband, father, or brother on their journey to Rome or, even more than that, traveled alone. 27 Female participation was fueled by the changing rationale behind the classic Grand Tour, but was also powered by external factors. Transport might have tipped the balance, as the expanding network of coach and barge services seriously lowered the risk and discomfort of early modern travel behavior. 28 Depending on the region, the impact of these changes varied significantly. In the Netherlands, wives and daughters were increasingly taken along on small domestic trips or beyond, but a full-fledged Grand Tour remained out of the question until the late eighteenth century. This point hints at some deeply ingrained cultural differences concerning the freedom of movement available to women. 29 Feminization eventually changed the Grand Tour itself, as Rosemary Sweet effectively argues. Women experimented with a different kind of gaze, as the eye of the connoisseur, evaluating paintings, sculpture, and architecture remained the realm of masculine politeness. Instead, manuscripts written by women were brimming with observations on everyday life in Italian cities, as they were forced to focus on more mundane topics. Eventually, this trope also became popular among men. 30

Gender also appears in another form. Masculinity was not a focus of analysis until, in the early 2010’s, experts began to explore the topic. Sarah Goldsmith analysed how the classic Grand Tour helped to create a strong, male identity. During the late eighteenth century, continental travel became a focus of derision and criticism, as it was whispered that well-bred English youths were turned into emasculated and effeminate fobs by their exposure to French and Italian manners. Goldsmith argues that tales of bravery and manliness, whereby travelers unflinchingly faced all sorts of dangers—steep mountain passes, yawning abysses, blistering cold, and other calamities—were used as a discursive strategy to gainsay this argument about degeneration. Unwanted feelings of fear and anxiety were deftly projected onto servants, who were frequently cast as milksops. 31 Of course, this theme of male bravery abroad was not only older than the eighteenth century, but it also lingered into the nineteenth century. 32 It can, however, explain why so many travelers turned their compass toward the Alps in the late eighteenth century, while the mountains had been largely ignored for ages. 33 At the same time, the classic Grand Tour also turned into a family experience, as men increasingly took their wives and children along. Unfortunately, there is little or no research on how these small cosmopolitans experienced their journey to Rome. 34