- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The 1971 Springboks: 'Coming between these blokes and their sport was the most dangerous thing I've done'

In this extract from his book Pitched Battle, Larry Writer details how Australia became a nation at war with itself when the apartheid-era all-white South African rugby team toured

I n 1971, when the racially selected all-white South African rugby team toured, Australia became a nation at war with itself. There was bloodshed as tens of thousands of anti-apartheid campaigners clashed with governments, police, and rugby fans. Following games in Perth, Adelaide, and Melbourne, the Springboks moved to true rugby territory: Sydney.

On 6 July, a cold, clear day, 300 police ringed the perimeter fence of the Sydney Cricket Ground. Barbed wire had been strung around it to deter climbers and hurdlers. Blue-overall-clad police wearing protective gloves prowled the sidelines, ready to defuse flares. Warnings to demonstrators that they would be arrested if they invaded the field boomed from the public-address system.

To deprive the demonstrators of opportunities to disrupt the match, there would be no preliminary games, no national anthems, no dignitaries shaking hands with the players as they lined up on the field before the kick-off. The captains’ coin toss would take place in the dressing room.

As match-time neared, the demonstrators paid their dollar entry charge at the turnstiles and entered the ground. Once inside, they made for the Hill on the eastern side of the SCG. There, now numbering around 2,500, they commenced to blow whistles and hooters, sing out slogans and protest anthems, and throw fireworks, flares, and other objects onto the field.

When the players ran on and the game got underway, the field was swathed in an acrid orange mist that constricted throats and made eyes stream.

A few rogue demonstrators threw balloons filled with tacks and sharp metal discs that were capable of slicing open the arm or leg of any player who fell on them. Police were pelted with golf balls. Demonstrators and rugby fans alike suffered cut heads when struck by flying beer cans. A police constable was hit in the face by a full can of beer. His gashed nose and forehead required six stitches. The thrower was pummelled by other officers. One protester huddled under a United Nations flag as pro-tour supporters’ tinnies rained upon her.

Although they were not sanctioned by rugby authorities as in Adelaide and Melbourne, rugby vigilantes, many of them drunk, attacked demonstrators. “Have a bath!” yelled the fans at the demonstrators. “Fascist pigs!” returned the protesters.

When paddy wagons were driven onto the ground, spectators cried, “Fill ’er up!” Police made 58 arrests, a significant number, but far fewer than in Melbourne. Generally, the Sydney police seemed less heavy-handed than their Melbourne counterparts. Officers at the SCG this day mostly waited for incidents to happen before they took action and then used only necessary force when making arrests. Inevitably, some police exceeded their brief, punching and headlocking arrested protesters who would have been happy to go quietly. Police also confiscated the cameras of an ABC-TV crew.

Officers didn’t flinch when fireworks exploded around their heads and at their feet. One constable’s cap flew off when a cracker exploded on his shoulder. He casually reached down, retrieved the cap, and placed it back on his head. Some police glared daggers, others smiled grimly – as if to say, “Is that the best you’ve got?” – at those who threw the bungers. The screech coming from the massed protesters – a shrill cacophony of whistles and horns, booing and yelling and screaming, and exploding tom-thumbs and bungers – sounded like a swarm of berserk cicadas.

The most spectacular arrest that day, one that made the front page of every newspaper in Australia and a number overseas and has gone down in protest folklore, was that of future New South Wales politician Meredith Burgmann.

“I went to the match disguised as a middle-aged South African rugby fan,” she says. “I wore a red wig and a horrible white cable-knit coat because I knew the police would stop anyone who looked like a demonstrator. From the kick-off, protesters had been trying to run onto the field without success.”

Burgmann and her sister Verity bided their time until ten minutes into the second half. Then, says Meredith, “We respectfully asked the police in front of us if they minded moving a little to the side because they were blocking our view of the match. They obliged, and as soon as the coppers’ backs were turned, we used our Esky to climb over the picket fence, and ran on. The police were taken by surprise. We ran like mad and made it to the middle of the field. Once among the players, we didn’t have a clue what to do next. It had never occurred to us that we’d ever get that far. So, as the game continued around us, I sat down on the grass, which seemed the obvious thing to do. Verity, however, was more adventurous. She grabbed the rugby ball and kicked it as hard as she could. The Bulletin called it the best kick of the match. Our invasion actually brought the game to a halt. I’m glad of that …

“And then the police got us. They were nasty, angry that we’d slipped through their cordon. They dragged me roughly hundreds of metres around the perimeter fence. They wouldn’t let me stand up. My metal watchband cut into my wrist and drew blood. All the rugger buggers ran down to the fence and screamed abuse and spat on me as I was being hauled past. I saw pure hatred in their faces. Coming between these blokes and their sport was the most dangerous thing I ever did.

“The crowd figure was 17,500, but I reckon everyone in Sydney must have been at the SCG that day because, even now, people say to me, “Oh, I was there when you ran onto the Cricket Ground.” When I die, as a respectable little old lady, that fact will be in every obituary. I’m proud of what my sister and I did. My parents were wonderful. They were not happy to see me being manhandled by the police and spat on, but they were proud of what I did, too.”

This is an edited extract from Pitched Battle – In the frontline of the 1971 Springbok tour of Australia, by Larry Writer (Scribe, $35)

- Rugby union

- Australian politics

- South Africa rugby team

Most viewed

Solidarity meetings

- Current Issue

- Issue archive

- Climate change

- Coronavirus

- Imperialism

- Islamophobia

- Labor Party

- Left debates

- Marxist theory

- Radical history

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Malaysia

1971 Springbok tour: When campaigners scored a victory against racism

The campaign against the South African Springboks tour is full of lessons for our campaigns against racism today, argues Tom Orsag

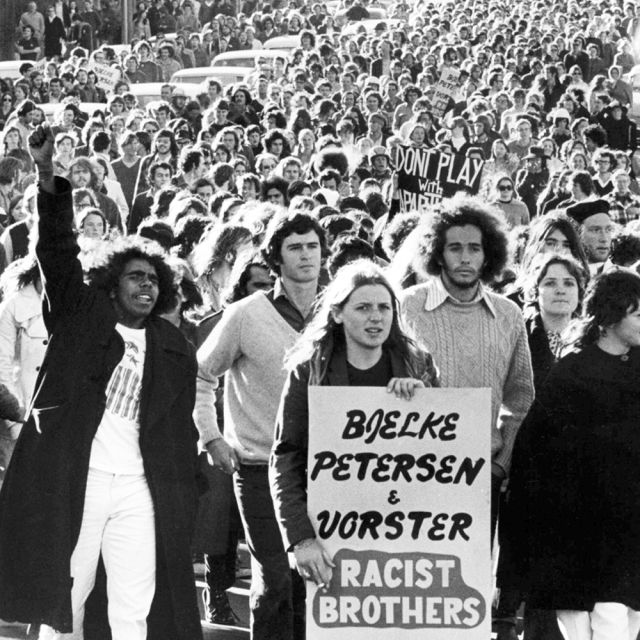

In 1971, the Australian Left scored a fantastic victory against racism. From late June to August, black and white people united in protest against the racist South African Springbok Rugby Union tour , in every major city.

No Apartheid-era sporting team ever toured Australia again, until the release of Nelson Mandela in 1994 and the end of Apartheid in South Africa .

Australia’s history—from the dispossession and genocide of Aboriginal people, and the exclusion of non-Europeans through the White Australia Policy—has left a deep-seated racism among sections of the population.

But the campaign against the Springbok tour showed the power of mass protest movements to undermine racism, and to draw wide sections of Australian workers and the trade union movement into anti-racist struggle.

Initially , 85 per cent of people surveyed in opinion polls were in favour of the tour. If the Liberal-National Party government had had its way the racist tours would have continued. They had planned to allow the South African cricket team to tour in the summer following the Springboks trip . Despite its racist Apartheid policies, in 1953, cricket tours by South Africa were called “precious” by Robert Menzies, Liberal Party founder and Prime Minister for 16 years.

The protests against the Springboks changed all that. The movement pushed Don Bradman, chair of the Australian Cricket Board , to issue a statement cancelling the South African cricket tour. But he didn’t hide behind the claim, “We can’t guarantee their safety”, as the movement had expected. He declared, “We will not play them until they chose a team on a non-racial basis.”

The mostly white student left, Aboriginal activists and the union movement united to make the Springboks unwelcome and to disrupt the games as best they could, given the massive police mobilisation by State Liberal governments. Henry Bolte, the Victorian Liberal Premier, declared the protests a “rebellion against constituted authority” .

At first, there were only very small committees organising in the early and mid-1960s against Apartheid in sport. After the struggle against the Vietnam War took off, racism in Australia began to be more seriously challenged.

In Sydney in 1969-70, there were small demonstrations against apartheid politicians, all-white netballers, surf lifesavers, tennis players and golfer Gary Player. In June 1969 the South African Trade Minister, Haak, visited. Four hundred people rallied in Sydney. A group of 200 tried to force their way into Haak’s hotel. Haak had come to offer South African investment in an alumina plant on Aboriginal land. Protests followed him in Brisbane and Melbourne, while Labor MP Gordon Bryant angrily argued against South African investment.

Racism in sport

Lloyd McDermott, the first Aboriginal person to play for the Australian Wallabies in 1962, felt he would be barred from touring South Africa in 1963, so he resigned from the Queensland squad that year, in order to avoid the controversy.

Tony Abrahams had toured South Africa with the Wallabies in 1969. While he didn’t like going, he felt he , “couldn’t get any real support for making a stand”. He was no radical, but what he saw in South Africa shocked him.

He told ABC radio in 2001, “Every aspect of South African life was completely affected by apartheid and not least in the sporting arena.” Sport and politics were intertwined in South Africa, which banned blacks from selection into the national sporting teams and banned blacks from foreign visiting teams.

He wrote a letter to the Sydney Morning Herald as the tour ended, which sparked a debate about a sporting boycott.

When asked how difficult it was to speak out against the 1971 tour, Abrahams said, “You’d certainly got a lot of nasty feedback in Australian society.” One player picked to play for Australia who refused to play against the racially-exclusive Springboks was counselled by one of the Australian selectors, who said the player was a victim of a communist conspiracy.

Abrahams was one of six Australian Wallabies who were against the tour—the others were Paul Darvenzia, Terry Foreman, Barry McDonald, James Roxborough and Bruce Taafe. Their decision was unprecedented: no Australian players had ever refused to represent Australia on political grounds. Prime Minister Billy McMahon called them “a disgrace to their country” .

Liberal Party leaders in Australia conveniently forgot this appalling racism when they defended the tour by saying, “sport and politics shouldn’t mix.”

Apartheid South Africa craved international acceptance through the medium of sport. The Liberal Government of Billy McMahon was happy to oblige.

Forgetting politics at all , for the sake of the dollar, the Minister for Primary Industry, National Party deputy Ian Sinclair, said South Africa was “a market of growing importance.”

Labor Opposition leader Gough Whitlam, SA Labor Premier Don Dunstan and WA Labor Premier John Tonkin spoke out against the tour.

But when the Springboks arrived on 26 June 1971, polite petitioning gave way to direct action.

The first games were held in Perth and Adelaide and were disrupted by university students. By then, the unions were already in support of the protests against the tour. At the top of the union movement, ACTU President Bob Hawke opposed the tour, as did individual unions who voted to implement bans. The scale of the union action against the tour made it almost physically impossible for it to go ahead.

Airline workers at TAA (the government-owned airline) and Ansett (the private one) banned carrying the Springboks. They were forced to travel around Australia by chartered light aircraft, with the Federal government having a RAAF Hercules standing by “just in case”. A ban was placed on the maintenance of South African Airways planes. The Springboks were refused admission to one of the largest wineries in the Barossa Valley. Unions banned them from nearly every club and hotel in Adelaide. Postal workers put a ban on all South African mail. The Waterside Workers Federation, forerunners of the MUA, banned South African ships and 4000 wharfies in Melbourne went on strike for one week against the tour.

In Melbourne, 650 police were out in force with truncheons, to face 5000 mainly student protesters. The police baton charged and rode horses into the protest outside Olympic Park in what Peter Hain, British anti-apartheid activist, described as “legalised thuggery”.

In Sydney, an official of the construction union—the NSW BLF—and another union member tried to saw off the goal posts at the Sydney Cricket Ground the night before the game .

The most reactionary of state premiers, the Queensland National Party’s Joh Bjelke-Peterson, declared a state of emergency for 30 days and made the Exhibition Ground into a fortress to deter the protesters. It was the first time in Western history that a State of Emergency was declared over a football match .

The Queensland annual budget for “special operations” in 1971 was $50,000. The total cost of the three-week police protection of the Springboks was more than $150,000. The Queensland government transferred 450 police from country areas to suppress anti-apartheid demonstrations. The Trades and Labour Council threatened a general strike in response to the State of Emergency. Over 700 people were arrested nationally.

The protests were a united front between members of the Labor Party, such as Peter Beattie and Wayne Goss, two future Labor Premiers of Queensland, Meredith Burgmann, future President of the NSW Upper House and socialists and revolutionaries of all hues—anarchists in Brisbane, Maoists in Melbourne, Trotskyists like Denis Freney in Sydney. Also involved were a variety of Aboriginal activists and radicals—Billy Craigie, Paul Coe and Gary Foley , Kevin Gilbert, Roberts Sykes, Dennis Walker, Liela Watson and Sam Watson, as well as a host of middle-class liberals.

Racism at home

The protests against apartheid laid the basis for deepening the struggle against racism towards Aboriginal people. Meredith Burgmann said, “One of the arguments that kept being raised by the apologists for the South Africans was ‘Well why don’t you clean up your own backyard? You know what’s happening to Aborigines’ . And in a funny way that was very healthy…Young Aboriginal activists of the time were very prominent in the demonstrations against the Springboks, so people like me had actually met and started working with Aboriginal activists.”

But not before the third anti-Vietnam War Moratorium rally in June 1971, in Sydney, when Paul Coe made a blistering speech, which Denis Freney described as “a brilliant speech, perhaps the best I’ve ever heard”. Meredith Burgmann described it as the “mother-fuckers speech”.

Coe criticised the protesters for being prepared to turn out en masse in support the oppressed people of all other countries but Australia. Coe argued said, “You raped our women, you stole our land, you massacred our ancestors, you destroyed our culture, and now—when we refused to die out as you expected—you want to kill us with your hypocrisy.”

The unity in the campaign against the Springbok tour opened up the possibility of a stronger campaign against the entrenched racism in Australia itself.

A leaflet issued at an anti-apartheid rally in December 1971 argued, “The demonstrations against the Springboks this year won a notable victory… Now we believe it is vital for anti-racists to turn their attention to racism here.” That they did with the unity of blacks and whites in their thousands to defend the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra in 1972.

Forty years on we need to celebrate the victory against the Springboks. It showed how grassroots movements can break down racist ideas—and should be an example and inspiration to campaigners against racism today.

The union action showed that it was possible to win large numbers of workers to anti-racist ideas and helped to push the arguments about opposing the tour deep into Australian society. The campaign was proof that demonstrations, strikes and broad-based movements are the key to shifting public opinion and defeating racism.

Latest articles

The hidden history of jewish anti-zionism and radicalism, albanese an accessory to murder as israel bombs and starves gaza, israel starving gazans to death, student gaza protest shows challenge ahead, ‘i’m comfortable’ says albanese as labor embraces offshore detention, charges against police possible over jai wright death, after the voice, albanese’s inaction on indigenous rights is exposed.

Solidarity is a socialist group with branches across Australia. We are opposed to the madness of capitalism, which is plunging us into global recession and misery at the same time as wrecking the planet’s future. We are taking the first steps towards building an organisation that can help lead the fight for an alternative system based on mass democratic planning, in the interests of human need not profit. Read more about Solidarity here or check out details of our meetings and events here.

Sign up for our newsletter

Arts and Culture

Climate and Ecology

The COVID-19 Crisis

Debate, comment and reviews

The economy

Gender and sexuality

Introduction to Socialism

Marxist theory

Oppression and Liberation

Revolts and Uprisings

Socialist strategy

Unions and workers

World politics and imperialism

Asia Pacific

Middle East

South and Central America

Red Flag is the publication of Socialist Alternative .

We're a revolutionary Marxist group based in Australia. We organise activism, public forums, and study groups. Our aim is to help rebuild a revolutionary movement in Australia, to do our bit in the worldwide fight against capitalism.

We put out Red Flag as a print publication every two weeks. It's the most widely read revolutionary publication in Australia. You can support our project by taking out a print or digital subscription .

We have branches all around the country. Find out how to make contact with us and get involved .

In 1971, the all-white South African rugby team, the Springboks, toured Australia. The six-week-long tour was met with a boycott campaign involving rolling protests, strikes and constant disruption. Thousands of people joined in what became an important step forward for the international campaign against apartheid and a pivotal moment in the struggle for Aboriginal rights in Australia.

In 1971, Gary Foley was living in Redfern, Sydney. He was one of a number of radical Aboriginal activists, known as the Redfern Black caucus or the Black Power movement, who were forging a new chapter in the history of Aboriginal resistance. These activists wanted to fight the state and change the world. They were militant and daring and were fast becoming connected with the left and the trade union movement. Gary and other Black Power leaders became some of the key figures in the campaign against the Springboks. He sat down with me to talk about the protests, 50 years on.

We start by talking about why the apartheid system provoked protests in Australia. “In much the same way that the global discussion about racism going on today was set off by events in America, the touchstone in the ’70s was the white racist regime in South Africa”, says Foley. “It was the big global issue to do with racism at the time and an international anti-apartheid campaign had been growing since the Sharpevillle massacre in 1960.

“The issue came to a head in Australia because the then Liberal government decided that the Springboks would be allowed to play in Australia. This was despite sporting ties with South Africa having been cut by many other countries and a significant part of the British Commonwealth at the time. Australia was determinedly resistant to the campaign to boycott South Africa.”

South African sporting tours had become a polarising issue internationally—cheered on by racists and reviled by anti-racists. The Liberal prime minister at the time, Billy MacMahon, was keen to show support for South Africa because, as Gary puts it, “Two of the biggest racist countries, they stick together. Don’t forget the apartheid system was consciously modelled on the Aboriginal Protection Act of 50 years earlier ... and, of course, support for South Africa was necessary to stop the supposed spread of communism and terrorism”.

At the same time that apartheid was becoming a focus, a range of other issues were radicalising young people, making the mood ripe for a militant campaign. “Vietnam was huge for everyone at the time. It demonstrated the racist, imperialist system we were up against”, says Gary. There were many reasons for Aboriginal people in particular to be opposed to the Vietnam War. As Gary explains, “We had started to pay attention to the radical Black literature, the radical Black politics that was coming out of the US. And apart from recognising that the Vietnamese were another group waging a struggle against colonialism, we agreed with what Muhammad Ali had said about the Vietcong: that ‘no Vietcong ever called me nigger’”.

The anti-Vietnam War movement was personal for many in Australia, especially young people. Australia sent substantial numbers of troops and introduced conscription. Gary was tipped off by fellow activist Paul Coe that Aboriginal people did not have to serve in the military. “So I sent in a letter asking for an exemption. But the horrible thing was basically no other Black people knew you could do this, so they signed them up and sent them to war ... two of my cousins had to serve in Vietnam, and they came back, as everyone else did, completely fucked up.”

Aboriginal activists like Gary made links with the student left through the anti-war movement, and became connected with left-wing trade unions and unionists through it. “You know we had really strong ties in Redfern with Jack Mundey’s Builders’ Labourers [Federation] up there, Bobby Pringle and Joey Owens, they were the fucking legends. Bobby Pringle got arrested with me on three occasions, once at the Redfern tent embassy, and twice fighting coppers in Redfern at the Empress Hotel. I mean, these were trade union officials who were prepared to put their bodies on the line in accordance with their principles; you don’t see too much of that these days.”

Despite the radical atmosphere at the time, Gary still recalls being surprised that “Almost immediately when it was announced that the tour would go ahead, out of nowhere—well at least that’s the way it appeared to me at the time—an anti-apartheid movement materialised. Suddenly there were thousands of white Australians out there demonstrating against apartheid”. He pauses and then adds, “Well, it was a surprise on one level but, maybe not so dramatic if you take into account that this was only three years or so since 90 percent of the population voted ‘yes’ in the 1967 referendum”. The “yes” vote was for rewording references to Aboriginal people in the constitution, in a ballot overwhelmingly seen as a referendum on racism. “This had indicated to us that there was a reservoir of good will but, much like today, this was largely emotive. The anti-apartheid campaign helped to turn this into active support.”

In the weeks before the Springboks arrived, the demonstrations against the tour were growing and public opposition was building. By the time they touched down in Perth, they had a major problem. “The ACTU had slapped a black ban on them, ironically, a black ban. And it held.” With the pilots, liquor and hotel workers unions on board, “They couldn’t get anyone to fly them anywhere, or serve them anything or rely on anywhere to stay”.

Gary is quick to point out that this wasn’t to do with Bob Hawke, then ACTU president and later Labor prime minister. “If it was left up to him as an individual, they would have walked right in. It was because of the key unions with clout and the principled trade union officials that Hawke was brought over.”

This hostile situation meant that the government and the rugby associations went to extreme lengths to keep the Springboks’ whereabouts secret, especially in Sydney, where the movement was strongest. But they didn’t always succeed. As Gary recalls, “The Redfern Black caucus had relocated from Redfern at the beginning of 1971 due to police harassment. We secretly shifted our headquarters to a double storey old house in Bondi Junction. Next door was a big carpark and on the other side of the road from this carpark was a motel called the Squire Inn. One night we came home and saw all these police everywhere and buses pulling up. We realised the next morning that this was the ‘super secret’ location the Springboks were staying at. And so we opened up our commune to the anti-apartheid mob and made them cups of tea and stuff while they held an almost permanent protest in the carpark outside the inn. We had lots of good rallies there, making as much noise as possible to keep them awake at all hours”.

As fortuitous as this was, the centrality of the Redfern Black caucus was, of course, more than incidental. All over the country, Aboriginal radicals played a key role in the protests. One particularly colourful incident involved Jim Boyce, a former Australian rugby player who had been to South Africa as part of an Australian tour and had become a prominent member of the moderate wing of the anti-apartheid movement, approaching Gary and the other Black Power activists with a proposal. “He had three genuine Springbok rugby jerseys, from the ritual at the end of every game—you know they swap jerseys and all that—and he said to us: ‘The Prime Minister of South Africa has said no Black man will ever wear this particular jersey. If you guys were to put these on and turn up at a demo it would make headlines in South Africa’. And so we did.

“Me and Billy Craigie grabbed a jersey each and we walked across the carpark and stood in front of the Squire Inn. We were caught by surprise by a bunch of plain-clothes NSW special branch guys: they come running out of the hotel and they grab us, and then they haul us into the hotel and started at us with “Where did you steal these? Who did you steal these from?’ They called down the entire Springbok team to look us up and down; one by one they walked past us. These big, angry racist rugby players looked like they wanted to murder us. And they probably would have if the coppers hadn’t been around.”

Audacious stunts like these helped raise the profile of Black Power activists and drew attention to the issue of anti-Aboriginal racism. In Brisbane, which was another centre for the movement, activists Kath Walker and Denis Walker “provocatively dined with poet Judith Wright at the Springboks’ Brisbane hotel”.

The audacity was not limited, however, to Aboriginal activists. Trade union activist John Phillips and Builders’ Labourers Federation president Bob Pringle walked into a sports ground in Paddington where the Springboks were due to play, and attempted to saw down the goal post. Leading anti-apartheid activists Verity and Meredith Burgmann posed as Afrikaans rugby goers and managed to invade the pitch at a high-profile game in Sydney. In Melbourne, one of the matches descended into a riot, with 200 protesters arrested. In Brisbane, a bitter fight took place. The authoritarian premier, Jo Bjelke-Petersen declared a state of emergency in order to protect the South African rugby entourage, and after protesters were brutalised at Tower Hill, a general strike was called. Across the country there were mass student meetings and mass demonstrations, with regular arrests.

The boycott campaign in Australia went further than similar campaigns in other countries. In particular, the union activity took things to a new level. Nowhere else had union bans been observed so strictly. The media attention on the campaign, both in Australia and internationally, helped fuel the growing opposition to apartheid, and laid the basis for even more confrontational actions, particularly the New Zealand anti-Springboks protests in 1981. Gary travelled to New Zealand to be part of these protests, and his eyes light up telling the story. “So there’s 25,0000 of us, and we’re marching around the perimeter of this rugby ground, and they’d set up this six-foot-high cyclone wire fence with barbed wire on top, all the way around. And so we were marching around, and all these rugby goers were standing up on the hill and yelling at us: ‘Go home you commo bastards! You’re weak as piss!’

“We must have been going around it on our second lap, when all of a sudden Rebecca Evans pulls out this megaphone and she says: ‘Operation Everest, Go!’ and then the front line of women suddenly turn and run as a group at the fence. We saw then that they were all wearing gloves. They just all leapt onto the top of the fence, and behind them a second line of women jumped onto the fence below them, forcing the fence down. As soon as these rugby supporters saw a flying wedge of women coming at them they scattered, and when they scattered they created a path onto the field, so 500 of us managed to get onto the field before the coppers closed the gap.”

Ultimately, it was not the international protests that dealt the decisive blow to the apartheid regime but the revolutionary uprising of black South African workers and youth. But international solidarity was important.

In the months and years following the fall of apartheid, world leaders who had been its open supporters or on the fence about it for years rushed to celebrate. Among these turncoats Gary includes Hawke, who, apart from being a “CIA stooge” and a “traitor to the union movement”, was a “hypocrite of the highest order” when it comes to pretending to have always been a passionate opponent of apartheid. Gary is also contemptuous of Nelson Mandela, as a “sell-out sucking up to the very people who called him a terrorist and a communist and supported his imprisonment”, a view Gary also very publicly expressed when Mandela visited Australia in 1990.

The most immediate and profound effect of the campaign against the Springboks in 1971 was the boost it gave to the Aboriginal rights movement, especially the struggle for land rights. Gary is clearly still moved thinking about this. “We were on a roll, and we argued to those joining the anti-apartheid movement that they needed to fight racism in their own backyard ... Paul Coe got up at one of the demonstrations and said: ‘You people need to start turning up at our land rights rallies or we will inevitably consider you hypocrites’. And to their credit, the leaders of the anti-apartheid movement accepted this challenge and began encouraging members of the movement to turn up to fight for Aboriginal rights.

“Our marches grew enormously as a result, and this gave us the momentum to set up the tent embassy ... The other thing that the anti-apartheid movement did was push Billy MacMahon, who was already a nervous, hapless, anxiety-ridden man, to become even more of a nervous wreck and to make a fatal political error by giving a speech on Invasion Day, 26 January 1972, about how he wasn’t going to do anything for Aboriginal rights. So out of this we said, ‘OK we will establish an embassy’. The embassy led to the single greatest breakthrough for Aboriginal rights, and the only time that any genuine land rights have ever been granted.”

When I ask him about what we might learn from this history that might be relevant to struggles today, Gary responds with optimism about the Black Lives Matter movement and the massive Invasion Day marches of recent years. “Those marches are pulling bigger crowds than we did. If 90,000 are prepared to come out on the streets for Invasion Day, that really shows that things can change, that we can start to shift consciousness.” But politics, as well as numbers, matters: “It can ironically be a hard thing to educate people about the nature of the boot that’s stomping on their neck but, what we need to do is get the 50 percent in Australia who are genuine about challenging racism ... and educate them as to the underlying cause, make them aware you can’t be anti-racist and pro-capitalist, it’s just a contradiction”.

Banyule City Council has become the eighth metro council in the Melbourne area to formally call for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza.

In a monumental betrayal, Melbourne University’s Students’ Council last month voted to rescind a motion supporting the Palestinian struggle for self-determination and the global Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement.

The truth, it turns out, won’t set you free: under capitalism it can get you locked up. That’s what Julian Assange discovered when he spoke truth to power.

The year is 2070. A global catastrophe—climate change, nuclear winter, civil war: pick your poison—recently ended civilisation and opened a new chapter in your life. So far you’ve ridden it out smoothly in your luxury bunker, but one day you’re swimming laps in the pool, living out your Bond-villain dream, when an alert blinks on your home security console.

The military ordered hundreds of thousands of people into a designated “safe” zone. On reaching it, they were shelled by the army and the air force. The generals said there was another safe zone; if the people kept moving, respite would be found. It wasn’t. Again they were attacked. The scene repeated, but now, corralled onto a tiny stretch of beach and trapped against the ocean, there was no way out.

“I will no longer be complicit in genocide. I’m about to engage in an extreme act of protest. But compared to what people have been experiencing in Palestine at the hands of their colonisers, it’s not extreme at all. This is what our ruling class has decided will be normal. Free Palestine.”

Marxist Left Review

Red Flag Radio podcast

Our YouTube channel

About Red Flag and Socialist Alternative

Subscribe to Red Flag

Marxism 2022

Red Flag is a publication of Socialist Alternative. Find out more about our group.

Red Flag's editors:

- Ben Hillier

- Eleanor Morley

- James Plested

- Louise O'Shea

Already subscribed?

Australians block cricket and impede rugby tour of apartheid South Africa, 1971

By Arielle Bernhardt

Introduction

Anti-apartheid protesters impeded the South African Springboks rugby tour, and stopped the cricket tour, to protest racial inequality.

To South Africans and Australians alike, rugby is not just a sport, but a cultural symbol. In the 1960s and early 1970s, it was also a unifying force between apartheid South Africa and its “white neighbor by the sea”—Australia. At the time, Australia had in place many racist policies that discriminated against Aboriginal peoples and the Australian public was only beginning to gain an awareness of both the domestic and international issues of human rights at stake. It was this growing awareness that pushed many in Australia to try to cut both economic and cultural ties with South Africa.

Sports provided an opportunity. Pro-apartheid white South Africans valued highly the chance to field their sports teams in competition with others in the British Commonwealth of Nations. The 1971 Australian tour by the South African Springbok rugby team offered a prime opportunity to build anti-apartheid expression because rugby was South Africa’s most popular sport and Australia was one of its few competitors.

The South African Prime Minister had told the Springboks that they represented not only their team, but also the apartheid South Africa way of life. Many Australians were keen to demonstrate that they disagreed with this way of life. Disrupting the six week tour would greatly anger white South Africans and provide a morale boost to anti-apartheid activists in South Africa.

Planning for the anti-Springbok campaign began in 1969 immediately after the tour was announced. Although an important goal for protesters was to disrupt and bring an end to the Springbok tour that ran from June to August in 1971, they knew this goal would be very difficult to accomplish. Firstly, when the tour began, it was supported by a vast majority of Australians, and was fully supported and aided by the Australian government. Protesters hoped to stop the tour both through convincing the public of the moral reasons against it and also through physically disrupting play.

However, stopping a rugby game is difficult because it is played in an enclosed arena and players are used to loud noises surrounding them. Shouting by protesters would not affect them much and police could easily keep protesters out of the arena. Because of this, anti-apartheid campaigners had a second goal: to prevent the South African cricket tour that was meant to follow the rugby tour.

Cricket fields are not enclosed, and so more difficult to police. Cricket players are also not used to a lot of noise, so it would be easier to break their concentration. This made cricket tours easier to physically disrupt. Also, cricket, like rugby, was a very important sport to both South Africans and Australians.

Campaign organizers began to rally protesters before the arrival of the South Africans through holding public meetings to raise awareness, handing out informational leaflets, and letter-writing to media and government sources. An anti-Springbok protester’s handbook was passed out that specifically instructed protesters to engage only in non-violent actions. Organizers also gained the support and partnership of church groups and unionists. A series of vigils was held prior to the tour, and unions began making plans to boycott certain activities that would aid the Springboks in any way. The Australia Council of Trade Unions, ACTU, announced that, among other things, it would impose a ban on servicing to airplanes carrying Springboks. Union members would also refrain from supplying liquor to hotels that accommodated the team and the factory that made police batons would not produce any for the duration of the tour. As one union leader put it, if capitalists could choose where to invest their money, unions could certainly express their feelings through choosing where to invest their labor.

Immediately upon arrival in Australia, the Springboks were subject to the actions of protesters. Demonstrators sat-in at the motels accommodating the team, restaurants where they ate, and essentially followed the team motorcade wherever it went. Most of the demonstrations, however, were concentrated on the rugby matches. There were many student participants in the protests, but also many members of the clergy and the greater community. Protesters blew whistles, held up placards, and ran onto the field if possible. Some also saluted and yelled “Sieg Heil,” in reference to the similarities between South Africa’s apartheid and the Nazi regime.

The most difficult obstacle that protesters had to contend with was the oppressive police presence. In Queensland, the government declared a state of emergency, thus allowing police officers to take more extreme measures in trying to maintain control. In all provinces, however, reports of police brutality were common.

Over 700 demonstrators were arrested during the course of the tour, and were even charged with the ‘crime of protesting’. There was some violence on the part of protesters, but most maintained a non-violent approach. In the end, though, the extreme and brutal measures taken by the government and by police backfired: word-of-mouth and media coverage of the repression caused a shift in public opinion. More and more people began to support the anti-apartheid activists.

Another drastic change in public opinion occurred when seven Australian rugby players decided to go on strike and join the anti-Springbok protest.

Until that point, many Australians disagreed with the protests because they felt that sports should be separate from politics. That the country’s top rugby players felt otherwise was very important in influencing public opinion. Awareness of apartheid grew among Australians, as well as an awareness of their domestic racial issues relating to Aboriginal people.

Although August came and the Springbok tour reached its end, the campaign still enjoyed many successes. Protesters managed to make the tour very difficult to run, and significantly disrupted many games. The tour was also not very profitable because attendance dropped sharply.

Furthermore, the campaign succeeded in achieving its second goal: preventing the upcoming South African cricket tour. The anti-Springbok campaign prompted both the Australian and South African leaders of their national cricket associations to speak out against policies that discriminated based on race. The huge importance of these announcements cannot be understated. Firstly, the leader of the Australian cricket organization could have easily explained his cancellation of the upcoming tour by stating that it would have cost too much and been too difficult to run it with the interference of the protesters. That in of itself would have been a victory for protesters because it would have meant that their disruptions were successful. But, instead, the leader decided to base his explanation on the ethical reason for canceling the tour. As an important figure in Australia, his denouncement of apartheid carried a lot of weight. In addition, that the leader of the cricket association in South Africa would speak out against his own regime meant a lot to campaigners.

Along with preventing the upcoming cricket tour, the campaign raised awareness among the Australian public about the South African apartheid regime. Before the tour, only 7 percent of Australians opposed maintaining sporting ties with South Africa. At the end of the tour, more than one third opposed maintaining sporting ties. This opposition grew quickly and by the end of the year, the new government announced in its platform that it would implement a policy that would not allow sporting visas to be allocated to teams that discriminated based on race.

Despite the fact that the anti-apartheid protesters did not end the Springbok tour, the campaign is an important part of Australia’s history. It boosted the morale of anti-apartheid activists in South Africa, and raised awareness of the issue among the Australian public. It also brought attention to Australia’s own discriminatory policies against Aboriginal people and sparked activism and new policies aimed at creating equality domestically as well as abroad.

- Australian Rugby. “Springbok Tour Protests Remembered,” Australian rugby. Rugby.com.au. 2001.

- Clark, Jennifer. “’The Wind of Change’ in Australia: Aborigines and the International Politics of Race, 1960-1972. The International History Review. 20:1. 1998. Pp.89-117

- Smith, Amanda. “Springboks 1971,” Radio National’s The sports factor. 2001.

- The Age. “Mild in the Streets”, theage.com.au. 2005

- Varney, Wendy. “Tackling Apartheid: Reflections on the 1971 Anti-Tour Campaign,” Gandhi Marg: the Quarterly Journal of the Gandhi Peace Foundation. 23:3. October-December 2001

- University of Wollongong, “Focus on Springbok tour on eve of anniversary”. University of Wollongong Media Releases. 2001.

The Global Nonviolent Action Database

See other case studies in The Global Nonviolent Action Database from Australia and around the world .

Explore Further

- The 1971 Springboks: ‘Coming between these blokes and their sport was the most dangerous thing I’ve done’ , The Guardian, Larry Writer, 9.10.2016

- The long shadow of racism in Australian sporting history, NITV- SBS, Kris Flanders, 12/4/2018

- People’s History Podcast – Episode 3 – Protesting the 1971 Springbok Tour of Australia

- 1971 Anti-Apartheid (Springbok) Protests, QLD, Australia – Contents: 10 film streams and 5 audio streams from Radical Times Archive

- Video – Anti-Apartheid Protests Create State of Emergency in Queensland: Springbok Tour – Queensland State Archives

- Political Football, ABC podcast about the Queensland protests

Related Resources

- Apartheid - South Africa

- Civil resistance

- Direct action - Non violent NVDA

- Movements_Campaigns - Anti apartheid

- Movements_Campaigns – Racism_Racial justice

- Protests_Rallies

- South Africa

- Springboks (Rugby Team)

- Author: Arielle Bernhardt

- Source: https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/index.php/content/australians-block-cricket-and-impede-rugby-tour-apartheid-south-africa-1971

- Organisation: The Global Nonviolent Action Database, Swarthmore College

- Location: Australia

- Release Date: 2010

Contact a Commons librarian if you would like to connect with the author

- Arts & Creativity

- Campaign Strategy

- Coalition Building

- Communications & Media

- Digital Campaigning

- First Nations Resources

- Fundraising

- Justice, Diversity & Inclusion

- Lobbying & Advocacy

- Nonviolent Direct Action

- Research & Archiving

- Theories of Change

- Working in Groups

Pin It on Pinterest

Program: The Sports Factor

Springboks 1971

- X (formerly Twitter)

Amanda Smith: On The Sports Factor this week, we're remembering a quite extraordinary period in our sporting history: the Springboks' visit to Australia in 1971. It's 30 years ago this week that the South African Rugby team arrived in Perth, to begin their six-week match tour around the country, a tour that divided Australia, that sparked bitter and violent anti-apartheid demonstrations and brought about a state of emergency in Queensland.

CHANTING: ' Go home racists, go home racists.. '

Newsreader: The Prime Minister, Mr McMahon said in Canberra today that Australia's international image had not been endangered by the tour of the Springbok Rugby Union team. Mr McMahon said the idea that Australia's image had been endangered was a false one, created by those who were disrupting the tour.

Commentator: Police have still got those noisy demonstrations on the Hill under control, and play goes its hard way.

Man: I don't think in the history of the world, most certainly not in the history of Australia has a state of emergency ever been declared over a game of football.

Amanda Smith: Well in recollecting the Springboks' tour of 1971, the reactions to that tour, and what it all meant, we'll hear from a number of people who were involved in quite different ways.

Tony Abrahams was a Rugby player who became known as one of the seven 'anti-apartheid Wallabies'. For him, the issue began in 1969, when he was selected to tour South Africa with the Wallabies. There was very little agitation against that tour at the time, but for Tony Abrahams, whether to go or not was a difficult personal decision.

Tony Abrahams: I thought a lot about it. I'd been in the Wallabies for the two years previously and had a pretty good chance of being selected, and it was a deep worry to me. I think probably what persuaded me to go in the end was that I couldn't get any real support for making a stand, and any stand without having seen the situation, would have been considered to be just a foolish gesture of one who didn't know.

Amanda Smith: Well as well as being a Rugby player Tony, were you a student radical type?

Tony Abrahams: No, in fact that was one of the things that marked all the Wallabies that made the stand in the end; none of us were heavily involved in active political life. I guess I was deeply engaged emotionally in the issue of politics and the social side of politics, but I wasn't an activist.

Amanda Smith: How did going to South Africa on that Wallabies' tour in 1969 then further increase your feelings, your opposition to the issue of racially selected sports teams and the apartheid regime?

Tony Abrahams: Well from the moment you got off the plane, you were conscious of this grotesque compromise in being there, and it was fascinating to me that it wasn't more obvious to the Rugby Union authorities. Every aspect of South African life was completely affected by apartheid and not least in the sporting arena, where we played against white teams in front of segregated or completely white audiences. Occasionally going up in a line-out or whatever you'd see a police baton come down on an African head merely because they consistently supported us, which was one of the most shocking and intense reminders of the degree to which black Africans were alienated by the system there, and the degree to which they were disadvantaged. I mean for people of a country to support the opposing team's victory is amazing.

Amanda Smith: Well you didn't come back to Australia with the rest of the team, you hitch-hiked around Southern Africa instead, and late in 1969 you wrote a letter which was published in The Sydney Morning Herald in Australia, which I think really sparked debate here regarding sporting boycotts of South Africa; what did your letter say?

Tony Abrahams: Well I drafted it actually in South Africa in the last days of the tour, but didn't post it until my hitch-hiking got me outside South Africa, and I think ironically I posted it in Rhodesia which was, despite the fact that having declared unilateral independence, seen to be freer on the ground than South Africa. And so it was published very early in September I think, and it basically said what had happened on tour, and spelt out in clear terms the compromise of Australia continuing to play against South Africa, both in terms of being seen as supporting apartheid and also in terms of being seen in the eyes of the world as being racist ourselves.

Amanda Smith: Former Australian Rugby player, Tony Abrahams.

Well back in Australia, the anti-apartheid movement was just getting off the ground. And sparked by Tony Abrahams' letter to The Sydney Morning Herald, calls for Australia to cut sporting ties with South Africa began to mount, because of the racially exclusive nature of South Africa's national sports teams. But just prior to the 1971 tour, the Springboks themselves were showing no signs of concern about the reception awaiting them in Australia. As John Highfield, the ABC's correspondent in South Africa at the time reported.

John Highfield: The lobby was crowded as selectors announced the Springboks side to tour Australia.

NAMES CALLED/CHEERS

John Highfield: I then asked team captain, Hannes Marais a 29-year-old university lecturer, if he was apprehensive about the forthcoming trip to Australia.

Hannes Marais: Well the team's only been selected tonight and we haven't even thought about that. We ignore it as far as possible because we're not a political team, we're a Rugby team, and we try to keep politics out of it. Our only object is to play the game, and where there are people opposed to us being there, we were invited there by the Australian Rugby Union. They invited us, and we're only there to do as they want us to do, and that is play against the Australian side.

Amanda Smith: Springboks Captain, Hannes Marais, speaking in 1971, before the tour to Australia got underway.

The Springboks' tour began with matches in Perth, then Adelaide and Melbourne. With each game, the protests grew, although the majority of Australians remained in favour of the tour. At the first match played in Sydney, demonstrators actually managed to get onto the ground, despite the enormous police presence.

Commentator: And at this moment, onto the field go the first two, three, four demonstrators of the afternoon. Three of them are women and one of them a long-haired boy in a windcheater, and they've gone right into the centre of the pitch amongst the players, and they are now enacting the first sit-in of this tour. The police will very soon have that under control .

Amanda Smith: Meredith Burgmann was one of those women arrested at the Sydney Cricket Ground. In 1971, she was a 23-year-old student, and one of the organisers of the anti-apartheid movement. These days, Meredith Burgmann is the President of the New South Wales Legislative Council, but she remembers the events of that day 30 years ago all too clearly.

Meredith Burgmann: Well, there were huge number of demonstrators over on the Hill area and there was smoke bombs, and there was this incredible noise and it was like sort of world war was happening over on that area. But I and my sister and two friends had borrowed members' tickets and we dressed up as Afrikaaners; I wore a red wig because otherwise I was too easily recognisable and the police would have arrested me as I was going into the ground. And we brought in a steel Esky with us and sat it right by the fence. And we discussed, in what we considered were Afrikaaner accents, the game, very loudly, and the police who were in front of us, there was one about every three feet along the perimeter of the ground, we eventually convinced them to move aside so that we could see the game better, and by this stage they were totally convinced that we were South Africans and they moved aside. And then ten minutes into the second half, we saw our chance, and we used the steel Esky as a sort of a ramp up over the fence, and off we went. And us four and one other guy were the only people who actually got onto the ground during that demonstration. And my sister actually got hold of the ball and the kicked it, and The Bulletin called it the best kick of the season. (laughs)

Amanda Smith: Well for that pitch invasion you were later sentenced to two months jail with hard labour. It seems an incredibly harsh sentence; did you serve the jail term?

Meredith Burgmann: I was in and out of jail various times during the hearing of the case, but eventually on appeal it was reduced to a suspended sentence.

Amanda Smith: So how did you become involved in the Stop the Tour protests in the first place, Meredith?

Meredith Burgmann: Well I'm a great footy fan and a great cricket fan, and I'd been to a . I think it was either a cricket or a footy match in the mid-'60s, and I think it was Dick Buckhorne, the Catholic priest from the country area who had organised to have these leaflets put under the windscreen wipers of all the cars in the car park, and I remember reading this and getting quite concerned about the issue and thinking Yes, we probably shouldn't be watching all-white South African teams. But then after I got to university and got more involved in anti-Vietnam protests, I became quite radicalised, and a group of us in 1969 formed the anti-apartheid movement, which was dedicated to stopping sporting contact with South Africa, and we started demonstrating against the all-white teams that were coming out. There were the women basketballers, there was the surf life savers, there were tennis players and of course there was always Gary Player, the golfer, and we set out to stop these sporting contacts.

Amanda Smith: Meredith Burgmann, one of the anti-apartheid demonstrators who was arrested numerous times during the Springboks' tour in 1971.

Now the man who had the job of co-ordinating the security and travel arrangements for the Springboks during the New South Wales leg of their tour was John Howard. Not the one who's now the Prime Minister, this John Howard is an accountant. And he was for many years an executive member of the Australian Rugby Union. In 1971, John was the Treasurer of the New South Wales Rugby Union, which is how he got the gig of looking after the Springboks, a job that turned out to be much bigger than John Howard had imagined it would be.

John Howard: Absolutely, and in fact while I had run various games and things, it was nothing in the scope of this, but as far as coverage was concerned and as far as actual requirements were concerned. In fact one thing I can vividly recall that whereas I expected to give some of my time, I ended up basically being available to the Springboks side the whole of the time they were in New South Wales.

Amanda Smith: How difficult was it to get that Springbok team around New South Wales for the time they were there?

John Howard: Believe it or not, it wasn't that hard at all. The biggest problems were early in the place, when the arrangements for travel by domestic carrier fell down with only weeks to go.

Amanda Smith: This was because both TAA and Ansett had decided they wouldn't fly the Springboks around the country?

John Howard: That's right, and they made that decision very late in the day, and of course if that could not have occurred, then the whole tour would have fallen over. Hazleton Airlines, based out near Orange, offered six small planes to do the job, and in fact they did it very, very well. And the movement from that point of view wasn't too bad at all.

Amanda Smith: At the time, John, what was your view on the demonstrations against the tour?

John Howard: Well at the time I don't pretend that a saw a connection with the visit of the South African side with their political scene back home. I also didn't feel (and I'm going back to how I felt at the time) that the demonstrations would achieve anything as far as the South African scene was concerned. To me, I felt that the government had decided that the tour could proceed and therefore I offered my services to ensure that that would carry on. If the government had said ' No, they can't come ', well obviously that would have been a thing accepted by me.

Amanda Smith: Well looking back 30 years, what's your view now, John? Was it the correct decision for Rugby officials and the Federal government of the day to welcome the South African team to Australia?

John Howard: Well I can only present you my view, and I would believe that given the circumstances at the time, and we are talking 30 years ago as you just said, Yes, I believe it was necessary to proceed. Certainly the situation in South Africa in my view could never be supported, and in fact if you'd asked me whether it could even proceed today, or even two years after they were here at the time, I'd say No, the tour couldn't even take place. As to whether or not it helped to bring down and break the walls of apartheid, I don't know if I can give you an answer to that.

Amanda Smith: So John, tell me more about what it felt like to be involved with that tour at that time.

John Howard: One of the things that I can recall as far as that was concerned was that one day you're an ordinary person, you're a volunteer in a sport, life goes on. The next day all of a sudden you're confronted with a large number of police, of motorcades, of demonstrators, of players arriving in small aeroplanes, things that you would not have even credited could occur. And it was something like a kaleidoscope of noise, of colour, of things happening all at once, and it really didn't sink in as to the involvement until well after the tour had actually finished.

Amanda Smith: And what were your kind of reflections at that time after the tour had finished?

John Howard: They were mainly centred on what actually was happening in the here and now, that is to say smoke bombs, demonstrations, police etc. They weren't actually philosophical considerations as to what it was because being involved on a day-to-day basis, what you had to do was simply get the job done, and it was only when it was all over and you had time to reflect back on the various crowd disturbances and other matters, that you could marvel at the enormity of what had actually happened to Australian Rugby.

Amanda Smith: Former Treasurer of the Australian, and New South Wales, Rugby Unions, John Howard, who co-ordinated the security and travel for the Springboks in 1971.

Well what was the impact of the demonstrations against the South African Rugby team in Australia? After all, the tour proceeded, no matches were cancelled, and the Springboks won every single game they played. Meredith Burgmann, one of the organisers of the protest movement, remains proud of what they achieved.

Meredith Burgmann: Oh well, if you look at a short-term gain, we did achieve what we were after which was cancelling the cricket tour.

Amanda Smith: Yes now this was the cricket tour that was due for later that year, with the South African team coming to Australia.

Meredith Burgmann: Yes. Absolutely. And we'd always felt it was a hard ask to actually stop the football tour because football can be played in quite a chaotic atmosphere, whereas cricket really can't. And so we were really concentrating on getting the cricket tour cancelled, and the Chairman of the Cricket Board was Sir Donald Bradman, and he started writing to me at this stage, asking me why we were demonstrating, and I'd write back and then he'd write back; we had this correspondence that went on for some time, and I'd send him information about what was happening in South Africa, and we were very pleased at the end when the Cricket Board announced that the South African cricketers would not be coming to Australia. They didn't say ' We can't guarantee their safety ', which is what we expected. Bradman actually said ' We will not play them until they choose a team on a non-racial basis ', and we were so pleased with that statement.

Amanda Smith: Do you think that the Springbok tour of 1971 and the protest against it, changed Australia in any way?

Meredith Burgmann: It certainly changed Australians' attitude towards South Africa and apartheid, and we stopped being seen as South Africa's white brother across the sea, which really was how we were looked on by the world, and how we really looked at ourselves. So it changed that attitude. But also one of the arguments that kept being raised by the apologists for the South Africans was ' Well why don't you clean up your own backyard? You know, look what's happening to Aborigines '. And in a funny way that was very healthy for the way in which the media had been treating Aboriginal issues. Of course the media started then to look at Aboriginal issues, and young Aboriginal activists of the time were very prominent in the demonstrations against the Springboks, and so people like me had actually met and started working with Aboriginal activists, and so I think it did start raising the whole issue of white Australia's relationship with Aboriginal Australia.

Amanda Smith: Well Meredith, in a week's time next Friday there's a dinner being held at Parliament House in Sydney to honour those seven former Wallaby players; tell me about that.

Meredith Burgmann: Yes, well they've always been my heroes. Whenever anyone has ever asked me who were my sporting heroes, I say ' Well the seven guys who organised against and refused to play the Springboks '. And I'd always meant to give them a 20-year dinner or a 25-year dinner, but we've eventually got around to it, and it's being held exactly 30 years to the day since that first match in Sydney, and we have a message from Nelson Mandela and the South African High Commissioner in Canberra, His Excellency Zolile Magugu will be there, and presenting the seven heroes with a certificate of appreciation from the South Africans about what they've done.

Amanda Smith: One of those seven anti-apartheid Wallabies being honoured next Friday is Tony Abrahams, who we heard from earlier. For Tony, while going to South Africa with the Wallabies in 1969 had been a difficult decision to make, he had no hesitation about where he stood in 1971.

Tony Abrahams: Oh well it was clear that I was just a non-starter, there was no question of my ever being a candidate for playing against the Springboks again.

Amanda Smith: Were you at any time criticised for having gone to South Africa to play Rugby in 1969 and then objecting to South Africa coming to play Rugby in Australia in 1971?

Tony Abrahams: Yes, I mean it became a bit amusing in the end that there were a series of bog-standard arguments which were used in most debates, and that was one of them: Why did you go in the first place? But when you consider the environment of the time and the fact that as far as previous Wallabies were concerned, there wasn't a conspiracy of silence, but you certainly didn't get any information which would enable you to make the decision. But more than that, I spoke to five or six people in prominent positions in law or in civil liberties or involved in the Aboriginal issue in Australia, such as Charlie Perkins, and with the exception of two at the time, they all said, ' Look, you should go and see it for yourself '. The other two swung into line later and said, ' You were right to go ', because I think that those two expected me not to do anything about it once I'd seen it for myself, and of course I did.

Amanda Smith: How difficult at that time Tony, was it for you to speak out against this issue?

Tony Abrahams: Against the background of what had been happening in the '60s, the gradual change in the stance of young people and the ease of the issue, the lack of ambiguity about it, it wasn't that difficult. I mean it seems to me, looking back on it, but even then, that it was probably one of the clearest issues you could make a stand on. You'd certainly got a lot of very nasty feedback in Australian society, but you were young and you felt that you had right on your side, and so it didn't matter much.

Amanda Smith: Well what was, and is, your view on why people were so adamant at the time that sport and politics don't mix, as was said over and over again?

Tony Abrahams: Well you make me think of the fact that even a year ago, I was speaking to a very famous gold medallist, an Olympian, who gave exactly that view, even today. But that doesn't take into account the fact that there are times when sportsmen do come up against politics in a way which is utterly compromising, and where it's unavoidable. But I think in Australia at the time, people were sheltered from that view, and hadn't evolved particularly. I think generally speaking people saw that politics and sport didn't mix, or said that they didn't. And in fact I found myself in the initial stages of the issue of whether to go to South Africa thinking along those lines myself. It was only as I thought it through that I realised that the compromise was such that you were a political being merely by the fact of taking the sporting field in those circumstances.

Amanda Smith: Tony Abrahams, who's a lawyer, and a former Australian Rugby International.

Now another former Australian Rugby International who protested against the Springboks' tour, was Lloyd McDermott. But Lloyd's story goes back much earlier than 1971. He's acknowledged as the first Aborigine to represent his country in Rugby Union. He played tests against the New Zealand All-Blacks in 1962. But the forthcoming tour of South Africa, in 1963, effectively put an end to Lloyd McDermott's days with the Wallabies.

Lloyd McDermott: The situation was, as you know, blacks or coloureds weren't allowed to tour South Africa. So I was placed in a very difficult position at the end of the 1962 season, where if I had have been selected for the Australian team, I might not have been allowed into the country because of the apartheid laws. On the other hand, if they wanted to relax the laws somewhat, I would have had to be seen as some sort of token white, an honorary white for the period of my tour, which I didn't find very tasteful at all. So I resigned from the Queensland squad and I forfeited, because of my beliefs, any chance of getting selected in the team.

Amanda Smith: And you actually switched to playing Rugby League.

Lloyd McDermott: Rugby League, yes, that's right.

Amanda Smith: How much knowledge and understanding of the political and racial system of South Africa did you have at that time which would have influenced your decision?

Lloyd McDermott: While I wasn't 100% politically astute, I was aware, because being an Aboriginal person myself, of the disadvantage that the South Africans suffer.

Amanda Smith: Well let's leap to the present day. It's nearly 40 years since you played for the Wallabies, and it's 30 years since the Springboks Australian tour of 1971. Tell me about the Australian Aboriginal schoolboy team which tours South Africa next month.

Lloyd McDermott: Yes, well perhaps I might give you a bit of background of how the team came about, Amanda. Gary Ella and myself and a number of Rugby buffs some eight or nine years ago, we thought it was a bit of a national disgrace that at that stage only five Aboriginal athletes had represented Australia at Rugby Union, and it wasn't hard to work out why that was, because it wasn't because of the lack of talent, it was another form of apartheid, and that apartheid was economic apartheid. The thing was, that where Rugby was played and taught was at the private schools, the rich GPS schools. So you didn't find Aboriginal and Islander students, or very rarely, were they able to get access to Rugby Union. So we decided that we would try and take the game to the Aboriginal youths ourselves. So we started off with a shoestring budget of about $8,000 to get the boys from the country and from the city to learn how to play Rugby Union.

So we're sort of in a position where it was unheard of 30 or 40 years ago, to have even an Aboriginal or a coloured person going to South Africa; now we're in the position of taking a whole team with us.

Amanda Smith: Well probably the highlight of the tour will be the Australian Aboriginal Fifteen playing a curtainraiser to the Wallabies-Springboks match in Pretoria on 28th July; in relation to I guess the bitter and divisive fights that went on over Rugby and South Africa, like in Australia in 1971 and your own experience, how do you view this tour, the Australian Aboriginal Schoolboy team going to play in South Africa?

Lloyd McDermott: Well I think it's a dream come true, because the team we take over, we see ourselves as the ambassadors for not only white Australia but for Aboriginal Australia as well. We think that we have a very talented team, so we are rather proud ambassadors for black Australia, and I think it could be only seen as encouragement for some of the black South African players, and let's hope, even though they have one or two in their side, that eventually they'll have four or five black Springboks.

I see this as total vindication of the actions taken by my black and white brothers and sisters who got arrested for demonstrating, and the thing is that we weren't ratbags, us people who fought against apartheid, we were seen as sort of ratbags; as a matter of fact one of the white players who was picked to play for Australia and refused to play against the all-white South African team, he was counselled by one of the Australian selectors to say that he'd been the victim of a communist conspiracy. You know, the thing was, and the thing is now, economic sanctions were important, but equally important were the sporting sanctions that brought down the regime of apartheid.

Amanda Smith: Lloyd McDermott, who's a barrister, a former Rugby player for Australia, and the patron of the Australian Aboriginal Schoolboy Fifteen, due to play a series of matches in South Africa next month.

And on that good news postscript to the controversy of the Springboks Rugby Tour of Australia 30 years ago, that's The Sports Factor for this week. Michael Shirrefs is the producer; I'm Amanda Smith. Thanks for your company.

Thirty years ago, the South African rugby team, the Springboks, arrived in Australia for a six week match tour.

Although supported by the Federal Government, the Springbok tour was deeply contoversial and divisive. It sparked anti-apartheid protests around the country, and a state of emergency was declared in Queensland.

On this 30th anniversary, a range of people involved offer their recollections, and views on how this tour changed Australia.

Lawyer TONY ABRAHAMS played with the Australian rugby team in South Africa in 1969, but became one of seven anti-apartheid Wallabies who spoke out against the 1971 tour. MEREDITH BURGMANN, now President of the New South Wales Legislative Council, was one of the organisers of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, arrested numerous times during the Springbok tour. Accountant JOHN HOWARD was the Treasurer of the New South Wales Rugby Union, and in charge of the Springboks' travel and security during the tour - a job that turned out to be much bigger than he'd expected!

And barrister LLOYD McDERMOTT was the first Aborigine to play with the Wallabies, in 1962, but was barred from touring to South Africa with the team in 1963. He's the patron of a young Aboriginal rugby team which this year played in South Africa. In his view it's the culmination of what all the protests were about in 1971.

- Tony Abrahams

- Meredith Burgmann

- John Howard

- Lloyd McDermott

- Amanda Smith, Presenter

- Michael Shirrefs, Producer

- What's on

- Catalogue Information collections Queensland Family history First Nations Art and design Caring for our collections Research

- Using the library Membership Ask a librarian Borrow and request Computers and internet Print, copy and scan Book spaces and equipment Justice of the Peace Venue hire GRAIL

- Getting here Opening hours Spaces Maps by level Food and facilities Access and inclusion

- First 5 Forever

- Awards and fellowships Caring for your collections Contribute to collections Donate Volunteer

- Contact us Corporate information Interim Truth and Treaty Body Jobs and employment News and media Partnerships and collaborations Pay an invoice

50th Anniversary of the ‘Tower Mill’ Protests

By Dr Anne Richards, author of 'A Book of Doors', a memoir of political protests in Brisbane in the late 1960s – early 1970s (guest blogger) | 23 July 2021

Demonstration outside the Tower Mill Motel during the South African Springbok Tour, 1971. Still from film by Peter Gray. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

The challenge was set. Brisbane Writers Festival [BWF] asked me to find the ex-Wallaby footballer who’d addressed over 1000 students at the University of Queensland refectory in mid-1971. I was 18 then, and never had any personal contact with the legendary Anthony Abrahams since he took a fearless stance against apartheid in South Africa.

I googled and searched, checked recent internet profiles, followed random leads. I spoke with a sympathetic young man at University of Sydney’s Alumni, and sent an email: ‘Anthony Abrahams AM, c/- Uni of Sydney Alumni. Please forward.’ Fingers crossed! The next evening, I received a call from Anthony. He gracefully accepted the invitation to speak at BWF’s special event , marking the 50th anniversary of the South African rugby union tour of Australia.

Film by Peter Gray showing the demonstration outside the Tower Mill Motel during the South African Springbok Tour, 1971. (State Library of Queensland collection)

There were dramatic and violent protests across Australia, but the violence experienced in Brisbane was extreme. Joh bussed in 600 additional country police to enforce his brand of law and order. Hundreds of police attacked peaceful demonstrators outside the Tower Mill motel and throughout the streets of Brisbane. Young and old activists braved the brutal force of police retaliation. Importantly, this tour and the resultant protests united young white radicals with the groundswell of black activism that had been growing through the 1960s to fight apartheid and racism here in Australia. That struggle continues.

Find out more about this Brisbane Writers Festival event at the University of Queensland - Political Football: The Radical Legacy of the Anti-Apartheid Protests in Brisbane .

State Library of Queensland collections include a variety of items relating to the history of protest movements in Queensland.

Examples of resources in State Library's collection relating to Queensland protest movements

- 1866 - Brisbane's Bread or Blood Riot (blog post)

- 1891 - Shearers' Strike (blog post)

- 1919 - Red Flag Riot (blog post)

- 1960s-1970s - Remembering the Revolution (blog post - various protest movements)

- 1960s-1970s - Our radical past: protest in 60s and 70s Brisbane (digital stories)

- 1967 - Civil Liberties March (film by Peter Gray)

- 1982 - State of Emergency - politics and protests surrounding the 1982 Commonwealth Games (past exhibition)

- 1983 - Daintree Blockade Photographs by Russell Francis (digitised photographs)

- 1989 - Break the silence: Rally for Gay law reform (blog post)

- 2000 - People's Walk for Reconciliation (blog post)

- 2003 - Anti-war protest in Brisbane - history in pictures (blog post)

- 2012 - Musgrave Park Tent Embassy Eviction and Protest photographs by Hamish Cairns (digital photographs)

- 2019 - Extinction Rebellion Brisbane Protest photographs by Hamish Cairns (digital photographs)

Please note - This is not an exhaustive list of Queensland's protest movements. For more information please consult our One Search catalogue or submit an enquiry through Ask Us .

Your email address will not be published.

We welcome relevant, respectful comments.

Plan your visit

Visit the NFSA Canberra

Our opening hours

Around the web

- Facebook Canberra

- YouTube NFSA

- YouTube NFSA Films

1800 067 274 [email protected] Contact us

Email sign up

Never miss a moment. Stories, news and experiences celebrating Australia's audiovisual culture direct to your inbox.

Support us to grow, preserve and share our collection of more than 100 years of film, sound, broadcast, games – priceless treasures that belong to all Australians.

Springboks at Manuka Oval, 1971